A Synthesis of Historical and Recent Reports of Grizzly Bears (Ursus Arctos) in the North Cascades Region

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Okanogan County Was Created in 1888 from Stevens County, and Is an Indian Word for "Rendezvous

Okanogan County was created in 1888 from Stevens County, and is an Indian word for "rendezvous. It is situated in the north central part of the state west of the Cascaded and bounded on the north by Canada. The first American post in the state was Fort Okanogan established in 1811 by Astor's Pacific Fur Company. In 1859 the county experienced a gold rush when placer gold was discovered on the Similkameen River. Steamboats reached the town of Okanogan two months of the year in the 1880s, but it was not until 1915 that the county had regular transportation service when the Great Northern Railroad ran a branch line from Wenatchee to Okanogan. Today, mining is an important part of the county's economy along with timber products and agriculture. Bounded by: British Columbia, Canada (N), Ferry County (E), Lincoln, Grant and Douglas counties (S), and Chelan, Skagit, and Whatcom counties (W). Chambers of Commerce: Brewster Chamber of Commerce, PO Box 1087, Brewster, WA 98812. Phone 509-689-3589, 509-689-3379. Fax 509-689-3705. Conconully Chamber of Commerce, PO Box 231, Conconully, WA 98819. Phone 509-826- 0813. Grand Coulee Dam Area Chamber of Commerce, Box 760, Grand Coulee, WA 99133. Phone 509-633-3074. Fax 509-633-1370. Okanogan Chamber of Commerce, PO Box 1125, Okanogan, WA 98840. Phone 509-422-9882. Omak Chamber of Commerce, 401 Omak Ave, Rt 2 Box 5200, Omak, WA 98841. Phone 509- 826-1880. Oroville Chamber of Commerce, PO Box 536, Oroville, WA 98844. Phone 509-476-2739. Pateros Chamber of Commerce, PO Box 613, Pateros, WA 98846. -

DOCUMENTS Journal of Occurrences at Nisqually House, 1833

DOCUMENTS Journal of Occurrences at Nisqually House, 1833 INTRODUCTION F art Nisqually was the first permanent settlement of white men on Puget Sound. Fort Vancouver had been headquarters since 1825 and Fort Langley was founded near the mouth of the Fraser river in 1827. Fort N isqually was, therefore, a station which served to link these two together. While the primary object of the Hudson's Bay Company was to collect furs, nevertheless, the great needs of their own trappers, and the needs of Russian America (Alaska), and the Hawaiian Islands and other places for foodstuffs, caused that Company to seriously think of entering into an agricultural form of enterprise. But certain of the directors were not in favor of having the Company branch out into other lines, so a subsidiary company, the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, was formed in 1838 for the purpose of taking advantage of the agri cultural opportunities of the Pacific. This company was financed and officered by members of the Hudson's Bay Company. From that time Fort Nisqually became more an agricultural enterprise than a fur-trad ing post. The Treaty of 1846, by which the United States received the sovereignty of the country to the south of the forty-ninth parallel of north latitude, promised the Hudson's Bay Company and the Puget Sound Agricultural Company that their possessions in that section would be respected. The antagonism of incoming settlers who coveted the fine lands aggravated the situation. Dr. William Fraser T olmie, as Super intendent of the Puget Sound Agricultural Company, remained in charge until 1859, when he removed to Victoria, and Edward Huggins, a clerk, was left as custodian at Nisqually. -

A History of Resource Use and Disturbance in Riverine Basins Of

Robert C. Wissmar,'Jeanetle E, Smith,'Bruce A. Mclntosh,,HiramW. Li,. Gordon H. Reeves.and James R. Sedell' A Historyof ResourceUse and Disturbancein RiverineBasins of Eastern Oregonand Washington(Early 1800s-1990s) Abstract Rj\( r n.rsr, rr Cds.lde u rl|alrlo|ogicso1c\|n|Slhalshrpedthepresent'dailalrlsraprlsrn l.ii\||sl'rn|e!nroddriParianecosrstctnsllllldr'li!l's|oi'L|!7jrgand anllril,rri!ndl.es.|edi1iiculttonanagebtaull]itl]cis|no{nlboU|holtheseecosrelnsfu dele|pprorrrlrrrr's|ortrl.rtingthesrInptonlsofd {ith pluns lbr resoliirg t h$itatscontinuetodeclile'Altlrrratjrrl|r.nrrrbusin\!jelnan!genentst' hoPel'orinlp|ornlgthee.os}sl.jn]h;odjl('tsi|\anrlpopuationlelelsoffshaldirj1d]jn''PrioIili(jsi|r(|ullc|hePf Nrtersheds (e.g.. roarll+: a Introduction to$,ards"natur-al conditions" that nleetLhe hislr)ri- tal requirernentsoffish and t'ildlile. Some rnajor As a resull of PresidentClirrton's ! orcst Summit qucstions that need to be ansrererl arc. "How hale in PortlandOrcgon cluring Spring 19913.consider- hisloricalccosvstcms iunctionecl and ho* nale ntr ablc attention is heing licusecl on thc inllucnccs man a( lions changcd them'/'' of hre-t .rn,l,'tlrr'r r, -urrrr. mJnlrepmpntl,f;r.ti, c- orr lhe health of l'acific No|th$'esLecosystems. This drrcumcntrcvict's the environmentalhis- l\{anagcrncnt recornmendations of an inLer-agr:ncv torr ol theinfl.r-n, '-,,f h',rrrunJ, ti\'ti, - in cJ-l tcanrol scicntistspoint to the urgenLneed frrr irn- ern O|cgon and Waslington over lhe pasl l\\o in ccosvstemm:uagement (Foresl lic- lr|1^emcnts centurie-s.The -

GEOLOGIC MAP of the Mccoy PEAK QUADRANGLE, SOUTHERN CASCADE RANGE, WASHINGTON

U.S. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Geologic map of the McCoy Peak quadrangle, southern Cascade Range, Washington by Donald A. Swanson1 Open-File Report 92-336 This report is preliminary and has not been reviewed for conformity with U.S. Geological Survey editorial standards or with the North American Stratigraphic Code. Any use of trade, firm, or product names is for descriptive purposes only and does not imply endorsement by the U.S. Government. 'U.S. Geological Survey, Department of Geological Sciences AJ-20, University of Washington, Seattle, Washington 98195 CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ........................ 1 5. Locations of samples collected in McCoy Peak ACKNOWLEDGMENTS ................... 1 {quadrangle ......................... 6 ROCK TERMINOLOGY AND CHEMICAL 6. Alkali-lime classification diagram for Tertiary CLASSIFICATION .................... 2 rocks in McCoy Peak quadrangle .......... 7 GENERAL GEOLOGY .................... 6 7. Plot of FeO*/MgO vs. SiO2 for rocks from TERTIARY ROCKS OLDER THAN INTRUSIVE McCoy Peak quadrangle ................ 7 SUITE OF KIDD CREEK ............... 7 8. Plot of total alkalis vs. SiO2 for rocks in McCoy Volcaniclastic rocks ................... 7 Peak quadrangle ..................... 8 Chaotic volcanic breccia ................ 8 9. Plot of K2O vs. SiO2 for rocks from McCoy Vitroclastic dacite and andesite breccia ...... 9 Peak quadrangle ..................... 8 Volcanic centers ...................... 10 10. Distrbution of pyroxene andesite and basaltic Regional dike swarm .................. 11 andesite dikes in French Butte, Greenhorn Age .............................. 13 Buttes, Tower Rock, and McCoy Peak INTRUSIVE SUITE OF KIDD CREEK ......... 13 quadrangles ........................ 12 Dikes ............................. 14 11. Rose diagrams of strikes of dikes and beds in Sills .............................. 16 McCoy Peak and other quadrangles ....... 13 Relation of dikes and sills ............... 16 12. Plcts of TiO2, FeO*, and MnO vs. -

Roadless Rule and Dark Divide the Dark Divide Was Once Much Larger Than Its Current 76,000 Acres

Exploring the PRING S RA Dark Divide I Despite its intimidating name, the Dark Divide is a place of sunny ridges and tremendous wildflower meadows. The region is endangered, however, by threats from off-road vehicle use. Southwest Washington’s threatened gem By Andrew Engelson soils and meadows. The region was A thick layer of ash from the 1980 excluded from the protections of the eruption of Mount St. Helens is still Don’t be afraid of the Dark Divide. 1984 Washington Wilderness Bill. prominent. Even with a somewhat ominous But hikers are slowly reclaiming the The region is home to a variety of name, this spectacular roadless area ridges with their boots. And there are forest ecosystems, all dependent on between Mount St. Helens and Mt. many reasons to go: unique geology, wildfires. Huge wildfires in the early Adams is actually filled with light: sun- abundant wildflowers and wildlife, 1900s left many of the open meadows baked ridges, subalpine forests, and and superb views. and silver-gray snags you’ll find there meadows exploding with wildflowers. The lava flows that are the founda- today. Even so, the region is home to Named for the 19th century miner tion of the 76,000-acre region are huge trees. Just outside the Dark and settler John Dark, the Dark approximately 20 to 25 million years Divide roadless area, you can find the Divide long served as hunting and old. Areas such as Juniper and world’s largest noble fir, near gathering grounds for American Langille Ridge were actually once Yellowjacket Creek. -

A G~Ographic Dictionary of Washington

' ' ., • I ,•,, ... I II•''• -. .. ' . '' . ... .; - . .II. • ~ ~ ,..,..\f •• ... • - WASHINGTON GEOLOGICAL SURVEY HENRY LANDES, State Geologist BULLETIN No. 17 A G~ographic Dictionary of Washington By HENRY LANDES OLYMPIA FRAN K M, LAMBORN ~PUBLIC PRINTER 1917 BOARD OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY. Governor ERNEST LISTER, Chairman. Lieutenant Governor Louis F. HART. State Treasurer W.W. SHERMAN, Secretary. President HENRY SuzzALLO. President ERNEST 0. HOLLAND. HENRY LANDES, State Geologist. LETTER OF TRANSMITTAL. Go,:ernor Ernest Lister, Chairman, and Members of the Board of Geological Survey: GENTLEMEN : I have the honor to submit herewith a report entitled "A Geographic Dictionary of Washington," with the recommendation that it be printed as Bulletin No. 17 of the Sun-ey reports. Very respectfully, HENRY LAKDES, State Geologist. University Station, Seattle, December 1, 1917. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page CHAPTER I. GENERAL INFORMATION............................. 7 I Location and Area................................... .. ... .. 7 Topography ... .... : . 8 Olympic Mountains . 8 Willapa Hills . • . 9 Puget Sound Basin. 10 Cascade Mountains . 11 Okanogan Highlands ................................ : ....' . 13 Columbia Plateau . 13 Blue Mountains ..................................... , . 15 Selkirk Mountains ......... : . : ... : .. : . 15 Clhnate . 16 Temperature ......... .' . .. 16 Rainfall . 19 United States Weather Bureau Stations....................... 38 Drainage . 38 Stream Gaging Stations. 42 Gradient of Columbia River. 44 Summary of Discharge -

Chapter 10. Mid-Columbia Recovery Unit—Upper Columbia River Basins Critical Habitat Unit

Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification: Rationale for Why Habitat is Essential, and Documentation of Occupancy Chapter 10. Mid-Columbia Recovery Unit—Upper Columbia River Basins Critical Habitat Unit 10.1 Methow River Critical Habitat Subunit ....................................................................... 325 10.2. Chelan River Critical Habitat Subunit ......................................................................... 337 10.3. Entiat River Critical Habitat Subunit ........................................................................... 341 10.4. Wenatchee River Critical Habitat Subunit ................................................................... 345 323 Bull Trout Final Critical Habitat Justification Chapter 10 U. S. Fish and Wildlife Service September 2010 Chapter 10. Upper Columbia River Basins Critical Habitat Unit The Upper Columbia River Basins CHU includes the entire drainages of three CHSUs in central and north-central Washington on the east slopes of the Cascade Range and east of the Columbia River between Wenatchee, Washington, and the Okanogan River drainage: (1) Wenatchee River CHSU in Chelan County; (2) Entiat River CHSU in Chelan County; and (3) Methow River CHSU in Okanogan County. The Upper Columbia River Basins CHU also includes the Lake Chelan and Okanogan basins which historically provided spawning and rearing and FMO habitat and currently the Chelan Basin is essential and provides for FMO habitat to support migratory bull trout in this CHU. No critical habitat is proposed in the Okanogan River at this time. Bull trout have been recently observed in the Okanogan River near Osoyoos Lake, but it is unclear if it is essential habitat and what role this drainage may play in recovery. A total of 1,074.9 km (667.9 mi) of streams and 1,033.2 ha (2,553.1 ac) of lake surface area in this CHU are proposed as critical habitat to provide for spawning and rearing, FMO habitat to support three core areas essential for conservation and recovery. -

Across the Cascade Range

Series I B> DescriPtive Geology- 4l Bulletin No. 235 \ D, Petrography and Mineralogy, DEPARTMENT'OF THE INTERIOR UNITED STATES GEOLOGICAL SURVEY CHARLES \). WALCOTT, Di HECTOR GEOLOGICAL RECONNAISSANCE ACROSS THE CASCADE RANGE NEAR THE FORTY-NINTH PARALLEL GEORGE OTIS SMITH AND FRANK C. CALKINS WASHINGTON GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 1904 Trri-o^) SL'BD C 0 N T E N T S. I'lliJO. Letter of transmittal. ---_--_---..-.._-_.____.._-______._....._.._____.._.. 9 Introduction-__-._.__,.__-.----._--._._.__..._....__....---_--__._.__.-.-_- 11 Scope of report ---.--_.____.._______-.--....._---.._...._.__ ._.- 11 Route followed ........................:......................... 12 Geography .............................................................. 12 Topography .......................................................... 12 Primary divisions of the region..--.........-.--.-.--.-.-.. 12 Okanogan Valley .................:.. ............................ 18 Cascade Range ...............:........,..._ ....^......i........ 13 General characteristics..._.....-.....-..----.--.----.-.-..-.. 13 Northern termination.,.---.....-......--.-.............._ 13 Subdivision .............................................. 14 Okanogan Mountains ........................................... 14 Hozonieen Range ............................................ 15 Skagit Mountains....-.... ......-.----....-.-----..-...--.--- 16 Drainage ..................................................... 17 Climate ...................................................... ...... 17 Roads and trails -

Fort Nisqually Markers for His History of Washington, Idaho and Montana

Fort Nisqually Markers 239 three thousand pages of manuscript. In Bancroft's bibliography for his History of Washington, Idaho and Montana is found "Morse, (Eldridge) Notes of Hist. and Res, of Wash. Territory 24 vols. ms." Mr. Morse also wrote reams of Indian legends which have disappeared from "the keeping of the last known custodian. His newspaper venture exhausted his savings and during the last years of his life he maintained himself by selling the products from his loved gardens near Snohomish. His son Ed. C. Morse is a mining engineer well known in Alaska and other parts of the Pacific Northwest. Fort Nisqually Markers On June 9, 1928, appropriate ceremonies commemorated the placing of markers at Fort Nisqually, first home of white men on the shores of Puget Sound. The settlement by the Hudson's Bay Company was begun there on May 30, 1833. The property now belongs to E. 1. Du Pont de Nemours & Company which corporation has sought to save and to mark the old buildings. The Washington State Historical Society, deeming this act worthy of public recognition, prepared a program of dedication. The presiding officer was President C. L. Babcock of the Washington State Historical Society. Music was furnished by the Fort Lewis Military Band. The address of welcome was given by Manager F. T. Beers of the Du Pont Powder works and at the request of President Babcock the response to that address was made by State Senator Walter S. Davis. W. P. Bonney, Secretary of the Washington State Historical Society, read from the old Hudson's Bay Company records the first day's entry in the daily journal of Fort Nisqually. -

Interpretation and Conclusions

"LIKE NUGGETS FROM A GOLD MINEu SEARCHING FOR BRICKS AND THEIR MAKERS IN 'THE OREGON COUNTRY' B~f' Kmtm (1 COfwer~ ;\ th¢...i, ...uhmineJ Ilt SOIl(mla Slale UFU vcr,il y 11'1 partial fulfiUlT'Ietlt of the fCqlJln:mcntfi for the dcgr~ of MASTER OF ARTS tn Copyright 2011 by Kristin O. Converse ii AUTHORlZAnON FOR REPRODUCnON OF MASTER'S THESISIPROJECT 1pM' pernlt"j(m I~ n:pnll.lm.:til.m of Ihi$ rhais in ib endrel)" \Ii' !tbout runt\er uuthorilAtlOO fn.)m me. on the condiHt)Jllhat the per",)f1 Of a,eocy rl;!'(lucMing reproduction the "'OS$. and 1:Jf't)vi~ proper ackruJwkd,rnem nf auth.:If'l'htp. III “LIKE NUGGETS FROM A GOLD MINE” SEARCHING FOR BRICKS AND THEIR MAKERS IN „THE OREGON COUNTRY‟ Thesis by Kristin O. Converse ABSTRACT Purpose of the Study: The history of the Pacific Northwest has favored large, extractive and national industries such as the fur trade, mining, lumbering, fishing and farming over smaller pioneer enterprises. This multi-disciplinary study attempts to address that oversight by focusing on the early brickmakers in „the Oregon Country‟. Using a combination of archaeometry and historical research, this study attempts to make use of a humble and under- appreciated artifact – brick – to flesh out the forgotten details of the emergence of the brick industry, its role in the shifting local economy, as well as its producers and their economic strategies. Procedure: Instrumental Neutron Activation Analysis was performed on 89 red, common bricks archaeologically recovered from Fort Vancouver and 113 comparative samples in an attempt to „source‟ the brick. -

GEOLOGIC MAP of the CHELAN 30-MINUTE by 60-MINUTE QUADRANGLE, WASHINGTON by R

DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR TO ACCOMPANY MAP I-1661 U.S. GEOLOGICAL SURVEY GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE CHELAN 30-MINUTE BY 60-MINUTE QUADRANGLE, WASHINGTON By R. W. Tabor, V. A. Frizzell, Jr., J. T. Whetten, R. B. Waitt, D. A. Swanson, G. R. Byerly, D. B. Booth, M. J. Hetherington, and R. E. Zartman INTRODUCTION Bedrock of the Chelan 1:100,000 quadrangle displays a long and varied geologic history (fig. 1). Pioneer geologic work in the quadrangle began with Bailey Willis (1887, 1903) and I. C. Russell (1893, 1900). A. C. Waters (1930, 1932, 1938) made the first definitive geologic studies in the area (fig. 2). He mapped and described the metamorphic rocks and the lavas of the Columbia River Basalt Group in the vicinity of Chelan as well as the arkoses within the Chiwaukum graben (fig. 1). B. M. Page (1939a, b) detailed much of the structure and petrology of the metamorphic and igneous rocks in the Chiwaukum Mountains, further described the arkoses, and, for the first time, defined the alpine glacial stages in the area. C. L. Willis (1950, 1953) was the first to recognize the Chiwaukum graben, one of the more significant structural features of the region. The pre-Tertiary schists and gneisses are continuous with rocks to the north included in the Skagit Metamorphic Suite of Misch (1966, p. 102-103). Peter Misch and his students established a framework of North Cascade metamorphic geology which underlies much of our construct, especially in the western part of the quadrangle. Our work began in 1975 and was essentially completed in 1980. -

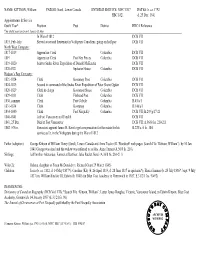

HBCA Biographical Sheet

NAME: KITTSON, William PARISH: Sorel, Lower Canada ENTERED SERVICE: NWC 1817 DATES: b. ca. 1792 HBC 1821 d. 25 Dec. 1841 Appointments & Service Outfit Year* Position Post District HBCA Reference *An Outfit year ran from 1 June to 31 May In War of 1812 DCB VII 1815, Feb.-July Served as second lieutenant in Voltigeurs Canadiens, going on half-pay DCB VII North West Company: 1817-1819 Apprentice Clerk Columbia DCB VII 1819 Apprentice Clerk Fort Nez Perces Columbia DCB VII 1819-1820 Sent to Snake River Expedition of Donald McKenzie DCB VII 1820-1821 Spokane House Columbia DCB VII Hudson’s Bay Company: 1821-1824 Clerk Kootenay Post Columbia DCB VII 1824-1825 Second in command of the Snake River Expedition of Peter Skene Ogden DCB VII 1826-1829 Clerk in charge Kootenae House Columbia DCB VII 1829-1831 Clerk Flathead Post Columbia DCB VII 1830, summer Clerk Fort Colvile Columbia B.45/a/1 1831-1834 Clerk Kootenay Columbia B.146/a/1 1834-1840 Clerk Fort Nisqually Columbia DCB VII; B.239/g/17-21 1840-1841 At Fort Vancouver in ill health DCB VII 1841, 25 Dec. Died at Fort Vancouver DCB VII; A.36/8 fos. 210-211 1842, 5 Nov. Executors appoint James H. Kerr to get compensation for the estate for his B.223/z /4 fo. 184 service as Lt. in the Voltigeurs during the War of 1812 Father (adoptive): George Kittson of William Henry (Sorel), Lower Canada and Anne Tucker (R. Woodruff web pages; Search File “Kittson, William”); by 10 Jan.