Traducciones / Translations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tes 3 the Mother of All Bombs

75 Nigel Coates 3 The Mother of all Bombs Freya Wigzell 8 The people here think I’m out of my mind Kristina Jaspers 20 The Adam’s Family Store Claire Zimmerman 28 Albert Kahn in the Second Industrial Revolution Laila Seewang 45 Ernst Litfaß and the Trickle-Down Effect Roberta Marcaccio 59 The Hero of Doubt Rebecca Siefert 71 Lauretta Vinciarelli, Illuminated Shantel Blakely 86 Solid Vision, or Mr Gropius Builds his Dream House Thomas Daniell 98 In Conversation with Shin Takamatsu Francesco Zuddas 119 The Idea of the Università Joanna Merwood-Salisbury 132 This is not a Skyscraper Victor Plahte Tschudi 150 Piranesi, Failed Photographer Francisco González de Canales 152 Eladio and the Whale Ross Anderson 163 The Appian Way Salomon Frausto 183 Sketches of a Utopian Pessimist Theo Crosby 189 The Painter as Designer Marco Biraghi 190 Poelzig and the Golem Zoë Slutzky 202 Dino Buzzati’s Ideal House 206 Contributors 75 224674_AA_75_interior.indd 1 22/11/2017 09:54 aa Files The contents of aa Files are derived from the activities Architectural Association of the Architectural Association School of Architecture. 36 Bedford Square Founded in 1847, the aa is the uk’s only independent London wc1b 3es school of architecture, offering undergraduate, t +44 (0)20 7887 4000 postgraduate and research degrees in architecture and f +44 (0)20 7414 0782 related fields. In addition, the Architectural Association aaschool.ac.uk is an international membership organisation, open to anyone with an interest in architecture. Publisher The Architectural Association -

Ankommen in Der Deutschen Lebenswelt

Europäisches Journal Europäisches Journal für Minderheitenfragen für Minderheitenfragen Contents Vol 9 No 1-2 2016 Editorial. 5 EJM Geleitwort Rita Süssmuth, Präsidentin a. D. des Deutschen Bundestages . 23 0 Hinführung . 27 Europäisches Journal für Minderheitenfragen 1 Kulturpolitik: das dritte Politikfeld gelingender Integration . 61 2 Zur Theorie der Kulturaneignung . .119 Vol 9 No 1-2 2016 3 Wie sind Menschen eigentlich? Anthropologische Möglichkeiten und Grenzen von Migranten-Enkulturation durch Kunst und Kultur . .157 4 Herausforderungen an das Kulturaneignungssystem . 175 Vol 9 No 1-2 2016 1-2 Vol 9 No Matthias Theodor Vogt, Erik Fritzsche, Christoph Meißelbach 5 Vier Experten-Ansichten. 217 5.1 Johann Heinrich Gottlob Justi 217 Ankommen 5.2 Siegfried Deinege 228 5.3 Werner J. Patzelt 236 in der deutschen Lebenswelt 5.4 Anton Sterbling 267 6 Die Sicht von Verantwortungsträgern in Wirtschaft, Migranten-Enkulturation und regionale Resilienz Politik und Kultur . 277 in der Einen Welt 7 Handlungsempfehlungen für eine erneuerte Migrations- und Integrationspolitik . 325 Nachwort Olaf Zimmermann, Geschäftsführer des Deutschen Kulturrates . 425 ISSN (Print) 1865-1089 ISSN (Online) 1865-1097 ISBN (Print) 978-3-8305-3716-8 ISBN (E-Book) 978-3-8305-2975-0 Europäisches Journal für Minderheitenfragen Vol 9 No 1-2 2016 Matthias Theodor Vogt, Erik Fritzsche, Christoph Meißelbach Ankommen in der deutschen Lebenswelt Migranten-Enkulturation und regionale Resilienz in der Einen Welt unter Mitarbeit von Sebastian Trept, Anselm Vogler, Simon Cremer, Jan Albrecht mit Beiträgen von Johann H. G. Justi, Siegfried Deinege, Werner J. Patzelt, Anton Sterbling und zahlreichen Verantwortungsträgern aus Wirtschaft, Politik und Kultur Geleitwort von Rita Süssmuth Nachwort von Olaf Zimmermann BWV • BERLINER WISSENSCHAFTS-VERLAG © BWV • BERLINER WISSENSCHAFTS-VERLAG GmbH Urheberrechtlich geschütztes Material. -

Benjamin and Koolhaas: History’S Afterlife Frances Hsu

65 Benjamin and Koolhaas: History’s Afterlife Frances Hsu Paris Benjamin intended his arcades project to be politi- Walter Benjamin called Paris the capital of the cally revolutionary. He worked on his opus while living nineteenth century. In his eponymous exposi- dangerously under Fascism as a refugee in Paris, tory exposé, written between 1935 and 1939, where, unable to secure an academic position, he he outlines a project to uncover the reality of the wrote for newspapers under various German pseu- recent past, the pre-history of modernity, through donyms. He had solicited support from the Institute the excavation of the ideologies, i.e., dreamworlds, for Social Research that was re-established in New embodied in material and cultural artefacts of the York in 1934 in association with Columbia University. nineteenth century. He used images to create a His project was unfinished at the end of the 1930s. history that would illuminate the contemporaneous He had collected numerous artefacts, drawings, workings of capital that had created the dreamlands photographs, texts, letters and papers – images of the city. The loci for the production of dream- reflecting the life of poets, artists, writers, workers, worlds were the arcades – pedestrian passages, engineers and others. He had also produced many situated between two masonry structures, that loose, handwritten pages organised into folders were lined on both sides with cafés, shops and that catalogued not only his early exposés but also other amusements and typically enclosed by an literary and philosophical passages from nineteenth iron and glass roof. Over three hundred arcades century sources and his observations, commen- were once scattered throughout the urban fabric taries and reflections for a theory and method of of Paris. -

Arte Povera, Press Release with Image Copy

SPROVIERI GIOVANNI ANSELMO, JANNIS KOUNELLIS, GIUSEPPE PENONE, EMILIO PRINI recent works preview 4 dec, 6 - 8 pm exhibition 5 dec - 16 feb 23 heddon street london w1b 4bq Sprovieri is delighted to present an exhibition of recent works by Giovanni Anselmo, Jannis Kounellis, Giuseppe Penone and Emilio Prini. The selection of works brings together some of the most influential living artists of the Arte Povera, the Italian artistic movement that in the late 1960s explored art not only using ‘poor materials’ but also conceiving the image as a conscious action rather than a representation of ideas and concepts. Ofering a contemporary transposition of their early subjects and practices, the exhibition reveals how these artists have continuously developed the energy and innovation of their poetics. The work ‘Ultramarine Blue While It Appears Towards Overseas’ by Giovanni Anselmo - especially conceived for this exhibition - reflects the artist’s commitment to create a work which must be ‘the physification of the force behind an action, of the energy of a situation or event’. A deep and bright blue square made with acrylic painting will be outlined by the artist against the white wall of the gallery. Jannis Kounellis contributes to the exhibition with a powerful triptych work: three large sculptures comprising of steel panels, iron beams and tar imprints of an ordinary man coat. The triptych translates the tension and alienation of our contemporary society where modernisation and industrial development are inevitably put in dialogue with our individual and traditional values. Giuseppe Penone’s sculpture ‘Acero (Maple)’ 2005 is inspired by the search for an equal relationship between man and material. -

Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin As Examples1

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE HISTORICAL URBAN FABRIC provided by Siberian Federal University Digital Repository UDC 711 Wang Haoyu, Li Zhenyu College of Architecture and Urban Planning, Tongji University, China, Shanghai, Yangpu District, Siping Road 1239, 200092 e-mail: [email protected], [email protected] COMPARISON STUDY OF TYPICAL HISTORICAL STREET SPACE BETWEEN CHINA AND GERMANY: FRIEDRICHSTRASSE IN BERLIN AND CENTRAL STREET IN HARBIN AS EXAMPLES1 Abstract: The article analyses the similarities and the differences of typical historical street space and urban fabric in China and Germany, taking Friedrichstrasse in Berlin and Central Street in Harbin as examples. The analysis mainly starts from four aspects: geographical environment, developing history, urban space fabric and building style. The two cities have similar geographical latitudes but different climate. Both of the two cities have a long history of development. As historical streets, both of the two streets are the main shopping street in the two cities respectively. The Berlin one is a famous luxury-shopping street while the Harbin one is a famous shopping destination for both citizens and tourists. As for the urban fabric, both streets have fishbone-like spatial structure but with different densities; both streets are pedestrian-friendly but with different scales; both have courtyards space structure but in different forms. Friedrichstrasse was divided into two parts during the World War II and it was partly ruined. It was rebuilt in IBA in the 1980s and many architectural masterpieces were designed by such world-known architects like O.M. -

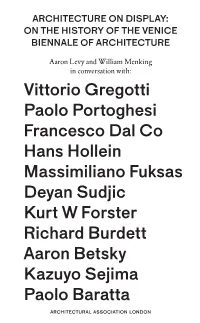

Architecture on Display: on the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture

archITECTURE ON DIspLAY: ON THE HISTORY OF THE VENICE BIENNALE OF archITECTURE Aaron Levy and William Menking in conversation with: Vittorio Gregotti Paolo Portoghesi Francesco Dal Co Hans Hollein Massimiliano Fuksas Deyan Sudjic Kurt W Forster Richard Burdett Aaron Betsky Kazuyo Sejima Paolo Baratta archITECTUraL assOCIATION LONDON ArchITECTURE ON DIspLAY Architecture on Display: On the History of the Venice Biennale of Architecture ARCHITECTURAL ASSOCIATION LONDON Contents 7 Preface by Brett Steele 11 Introduction by Aaron Levy Interviews 21 Vittorio Gregotti 35 Paolo Portoghesi 49 Francesco Dal Co 65 Hans Hollein 79 Massimiliano Fuksas 93 Deyan Sudjic 105 Kurt W Forster 127 Richard Burdett 141 Aaron Betsky 165 Kazuyo Sejima 181 Paolo Baratta 203 Afterword by William Menking 5 Preface Brett Steele The Venice Biennale of Architecture is an integral part of contemporary architectural culture. And not only for its arrival, like clockwork, every 730 days (every other August) as the rolling index of curatorial (much more than material, social or spatial) instincts within the world of architecture. The biennale’s importance today lies in its vital dual presence as both register and infrastructure, recording the impulses that guide not only architec- ture but also the increasingly international audienc- es created by (and so often today, nearly subservient to) contemporary architectures of display. As the title of this elegant book suggests, ‘architecture on display’ is indeed the larger cultural condition serving as context for the popular success and 30- year evolution of this remarkable event. To look past its most prosaic features as an architectural gathering measured by crowd size and exhibitor prowess, the biennale has become something much more than merely a regularly scheduled (if at times unpredictably organised) survey of architectural experimentation: it is now the key global embodiment of the curatorial bias of not only contemporary culture but also architectural life, or at least of how we imagine, represent and display that life. -

Annual Report 2013-2014

The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston Arts, Fine of Museum The μ˙ μ˙ μ˙ The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston annual report 2013–2014 THE MUSEUM OF FINE ARTS, HOUSTON, WARMLY THANKS THE 1,183 DOCENTS, VOLUNTEERS, AND MEMBERS OF THE MUSEUM’S GUILD FOR THEIR EXTRAORDINARY DEDICATION AND COMMITMENT. ANNUAL REPORT ANNUAL 2013–2014 Cover: GIUSEPPE PENONE Italian, born 1947 Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012 Bronze with gold leaf 433 1/16 x 96 3/4 x 79 in. (1100 x 245.7 x 200.7 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.728 While arboreal imagery has dominated Giuseppe Penone’s sculptures across his career, monumental bronzes of storm- blasted trees have only recently appeared as major themes in his work. Albero folgorato (Thunderstuck Tree), 2012, is the culmination of this series. Cast in bronze from a willow that had been struck by lightning, it both captures a moment in time and stands fixed as a profoundly evocative and timeless monument. ALG Opposite: LYONEL FEININGER American, 1871–1956 Self-Portrait, 1915 Oil on canvas 39 1/2 x 31 1/2 in. (100.3 x 80 cm) Museum purchase funded by the Caroline Wiess Law Accessions Endowment Fund 2014.756 Lyonel Feininger’s 1915 self-portrait unites the psychological urgency of German Expressionism with the formal structures of Cubism to reveal the artist’s profound isolation as a man in self-imposed exile, an American of German descent, who found himself an alien enemy living in Germany at the outbreak of World War I. -

Questions of Fashion

http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1086/677870 . Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The University of Chicago Press and Bard Graduate Center are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to West 86th. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 185.16.163.10 on Tue, 23 Jun 2015 06:24:53 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Questions of Fashion Lilly Reich Introduction by Robin Schuldenfrei Translated by Annika Fisher This article, titled “Modefragen,” was originally published in Die Form: Monatsschrift für gestaltende Arbeit, 1922. 102 West 86th V 21 N 1 This content downloaded from 185.16.163.10 on Tue, 23 Jun 2015 06:24:53 AM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Introduction In “Questions of Fashion,” Lilly Reich (1885–1947) introduces readers of the journal Die Form to recent developments in the design of clothing with respect to problems of the age.1 Reich, who had her own long-established atelier in Berlin, succinctly contextualizes issues that were already mainstays for the Werkbund, the prominent alliance of designers, businessmen, and government figures committed to raising design standards in Germany, of which she was a member. -

“Shall We Compete?”

5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall We Compete?” Pedro Guilherme 35 5th International Conference on Competitions 2014 Delft “Shall we compete?” Author Pedro Miguel Hernandez Salvador Guilherme1 CHAIA (Centre for Art History and Artistic Research), Universidade de Évora, Portugal http://uevora.academia.edu/PedroGuilherme (+351) 962556435 [email protected] Abstract Following previous research on competitions from Portuguese architects abroad we propose to show a risomatic string of politic, economic and sociologic events that show why competitions are so much appealing. We will follow Álvaro Siza Vieira and Eduardo Souto de Moura as the former opens the first doors to competitions and the latter follows the master with renewed strength and research vigour. The European convergence provides the opportunity to develop and confirm other architects whose competences and aesthetics are internationally known and recognized. Competitions become an opportunity to other work, different scales and strategies. By 2000, the downfall of the golden initial European years makes competitions not only an opportunity but the only opportunity for young architects. From the early tentative, explorative years of Siza’s firs competitions to the current massive participation of Portuguese architects in foreign competitions there is a long, cumulative effort of competence and visibility that gives international competitions a symbolic, unquestioned value. Keywords International Architectural Competitions, Portugal, Souto de Moura, Siza Vieira, research, decision making Introduction Architects have for long been competing among themselves in competitions. They have done so because they believed competitions are worth it, despite all its negative aspects. There are immense resources allocated in competitions: human labour, time, competences, stamina, expertizes, costs, energy and materials. -

Purcell IAWA Archivist Report 2012-2013 Draft.Docx.Docx

1 Archivist’s Report, FY 2013-2014 International Archives of Women in Architecture (IAWA) By Aaron D. Purcell Director of Special Collections and IAWA Archivist Overview During the past year, Special Collections continued its joint partnership with the College of Architecture and Urban Studies to acquire, arrange, describe, provide access to, and promote IAWA collections. Sherrie Bowser led the effort to process, acquire, and promote IAWA collections. With the help of students and other staff she accessioned 8 new collections and processed 6 collections. In spring 2014, Sherrie Bowser moved on to another professional position in Illinois. In October 2014, Samantha Winn began work as Collections Archivist, with responsibilities for IAWA collections. Collection Highlights ● Special Collections received 8 new IAWA collections during the past year, totaling 18.2 cubic feet of material and more than 274 Mb of digital photographs. (See Appendix 1, Acquired Accessions) ● With the help of staff, 7 IAWA collections were processed over the past year, totaling 33.6 cubic feet. (See Appendix 2, Processed Collections) ● There are now approximately 425 distinct IAWA collections totaling 1,787 cubic feet. ● Made 13 book purchases that that directly support IAWA collections (See Appendix 3, New Purchases) ● Spring 2014, visit to Linda Kiisk in Sacramento, California to appraise and ship back her collection to Virginia Tech Research, Promotion, and Selected Uses of IAWA Collections ● Held open house and sponsored exhibit for the 50th Anniversary of CAUS, Fall 2014 ● Assisted Robert Holton, Milka Bliznakov Research Prize winner, with onsite research on the role and contribution of Natalie de Blois in the design of three SOM projects (Lever House, Pepsi-Cola Headquarters, and Union Carbide) completed in New York City between 1950-1960 ● Exhibit in Special Collections, IAWA: Examples of women’s opportunities in architecture and design education, 1865-1993,” Fall 2013 ● Assisted Donna Dunay’s 1st year studio class (ca. -

E in M Ag Azin Vo N

Ein Magazin von T L 1 Liebe Leserinnen und Leser, im Jahr 2019 feiert Deutschland 100 Jahre Bauhaus und wir fast vier Jahrzehnte TEcnoLuMEn. 140 Jahre Tradition – eine Vergan - genheit voller Geschichten, die wir Ihnen erzählen wollen. Die Wagenfeld-Leuchte ist ohne Eine davon beginnt 1919 in Weimar. Zweifel eine dieser zeitlosen Walter Gropius gründete das Designikonen und seit fast 40 Jahren Staatliche Bauhaus, eine Schule, is t sie ganz sicher das bekannteste in der Kunst und Handwerk Werkstück unseres Hauses. auf einzigartige Weise zusammen - Das ist unsere Geschichte. geführt wurden. Interdisziplinär, Weshalb TEcnoLuMEn autorisierter weltoffen und experimentierfreudig. Hersteller dieser Leuchte ist, wer ob Architektur, Möbel, Foto- das Bremer unternehmen gegründet grafie, Silberwaren – Meister und hat, welche Designleuchten wir Studierende des Bauhaus schufen neben diesem und anderen Klassi - viele Klassiker. kern außerdem im Sortiment haben und welche Philosophie wir bei TEcnoLuMEn verfolgen, all das möchten wir Ihnen auf den folgen - den Seiten unseres Magazins erzählen. Weil Zukunft Vergangenes und Gegenwärtiges braucht. und das Heute ohne Geschichten nicht möglich ist. Wir freuen uns sehr, Ihnen die erste Ausgabe unseres TEcnoLuMEn Magazins TL1 vorstellen zu können 4 und wünschen Ihnen eine interes - Die Idee des Bauhaus sante und erkenntnisreiche Lektüre. 6 Die TEcnoLuMEn Geschichte carsten Hotzan 8 Interview mit Walter Schnepel Geschäftsführer 12 Alles Handarbeit 14 Designikone im Licht der Kunst 16 „Junge Designer“ r e n g e i l F m i h c a o J Die von Wilhelm Wagenfeld 1924 entworfene und im Staatlichen Bauhaus Weimar hergestellte Metallversion der „Bauhaus-Leuchte“. Herbert Bayer „Eine solche Resonanz kann man nicht Max Bill Laszlo Moholy-nagy mit organisation erreichen und nicht mit Propaganda. -

Bibliography

SELECTED bibliOgraPhy “Komentó: Gendai bijutsu no dōkō ten” [Comment: “Sakkazō no gakai: Chikaku wa kyobō nanoka” “Kiki ni tatsu gendai bijutsu: henkaku no fūka Trends in contemporary art exhibitions]. Kyoto [The collapse of the artist portrait: Is perception a aratana nihirizumu no tōrai ga” [The crisis of Compiled by Mika Yoshitake National Museum of Art, 1969. delusion?]. Yomiuri Newspaper, Dec. 21, 1969. contemporary art: The erosion of change, the coming of a new nihilism]. Yomiuri Newspaper, “Happening no nai Happening” [A Happening “Soku no sekai” [The world as it is]. In Ba So Ji OPEN July 17, 1971. without a Happening]. Interia, no. 122 (May 1969): (Place-Phase-Time), edited by Sekine Nobuo. Tokyo: pp. 44–45. privately printed, 1970. “Obŭje sasang ŭi chŏngch’ewa kŭ haengbang” [The identity and place of objet ideology]. Hongik Misul “Sekai to kōzō: Taishō no gakai (gendai bijutsu “Ningen no kaitai” [Dismantling the human being]. (1972). ronkō)” [World and structure: Collapse of the object SD, no. 63 (Jan. 1970): pp. 83–87. (Theory on contemporary art)]. Design hihyō, no. 9 “Hyōgen ni okeru riaritī no yōsei” [The call for the Publication information has been provided to the greatest extent available. (June 1969): pp. 121–33. “Deai o motomete” (Tokushū: Hatsugen suru reality of expression]. Bijutsu techō 24, no. 351 shinjin tachi: Higeijutsu no chihei kara) [In search of (Jan. 1972): pp. 70–74. “Sonzai to mu o koete: Sekine Nobuo-ron” [Beyond encounter (Special issue: Voices of new artists: From being and nothingness: On Sekine Nobuo]. Sansai, the realm of nonart)]. Bijutsu techō, no.