Copenhagen Interpretation Delenda Est?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2018 Annual Report Alfred P

2018 Annual Report Alfred P. Sloan Foundation $ 2018 Annual Report Contents Preface II Mission Statement III From the President IV The Year in Discovery VI About the Grants Listing 1 2018 Grants by Program 2 2018 Financial Review 101 Audited Financial Statements and Schedules 103 Board of Trustees 133 Officers and Staff 134 Index of 2018 Grant Recipients 135 Cover: The Sloan Foundation Telescope at Apache Point Observatory, New Mexico as it appeared in May 1998, when it achieved first light as the primary instrument of the Sloan Digital Sky Survey. An early set of images is shown superimposed on the sky behind it. (CREDIT: DAN LONG, APACHE POINT OBSERVATORY) I Alfred P. Sloan Foundation $ 2018 Annual Report Preface The ALFRED P. SLOAN FOUNDATION administers a private fund for the benefit of the public. It accordingly recognizes the responsibility of making periodic reports to the public on the management of this fund. The Foundation therefore submits this public report for the year 2018. II Alfred P. Sloan Foundation $ 2018 Annual Report Mission Statement The ALFRED P. SLOAN FOUNDATION makes grants primarily to support original research and education related to science, technology, engineering, mathematics, and economics. The Foundation believes that these fields—and the scholars and practitioners who work in them—are chief drivers of the nation’s health and prosperity. The Foundation also believes that a reasoned, systematic understanding of the forces of nature and society, when applied inventively and wisely, can lead to a better world for all. III Alfred P. Sloan Foundation $ 2018 Annual Report From the President ADAM F. -

Complementary & the Copenhagen Interpretation

Complementarity and the Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics Click here to go to the UPSCALE home page. Click here to go to the Physics Virtual Bookshelf home page. Introduction Neils Bohr (1885 - 1962) was one of the giants in the development of Quantum Mechanics. He is best known for: 1. The development of the Bohr Model of the Atom in 1913. A small document on this topic is available here. 2. The principle of Complementarity, the "heart" of Bohr's search for the significance of the quantum idea. This principle led him to: 3. The Copenhagen Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics. In this document we discuss Complementarity and then the Copenhagen Interpretation. But first we shall briefly discuss the general issue of interpretations of Quantum Mechanics, and briefly describe two interpretations. The discussion assumes some knowledge of the Feynman Double Slit, such as is discussed here; it also assumes some knowledge of Schrödinger's Cat, such as is discussed here. Finally, further discussion of interpretations of Quantum Mechanics can be meaningfully given with some knowledge of Bell's Theorem; a document on that topic is here. The level of discussion in what follows is based on an upper-year liberal arts course in modern physics without mathematics given at the University of Toronto. In that context, the discussion of Bell's Theorem mentioned in the previous paragraph is deferred until later. A recommended reference on the material discussed below is: F. David Peat, Einstein's Moon (Contemporary Books, 1990), ISBN 0-8092-4512-4 (cloth), 0-8092-3965-5 (paper). Interpretations of Quantum Mechanics Although the basic mathematical formalism of Quantum Mechanics was developed independently by Heisenberg and Schrödinger in 1926, a full and accepted interpretation of what that mathematics means still eludes us. -

Bohr's Complementarity and Kant's Epistemology

Bohr, 1913-2013, S´eminairePoincar´eXVII (2013) 145 { 166 S´eminairePoincar´e Bohr's Complementarity and Kant's Epistemology Michel Bitbol Archives Husserl ENS - CNRS 45, rue d'Ulm 75005 Paris, France Stefano Osnaghi ICI - Berlin Christinenstraße 18-19 10119, Berlin, Germany Abstract. We point out and analyze some striking analogies between Kant's transcendental method in philosophy and Bohr's approach of the fundamental issues raised by quantum mechanics. We argue in particular that some of the most controversial aspects of Bohr's views, as well as the philosophical concerns that led him to endorse such views, can naturally be understood along the lines of Kant's celebrated `Copernican' revolution in epistemology. 1 Introduction Contrary to received wisdom, Bohr's views on quantum mechanics did not gain uni- versal acceptance among physicists, even during the heyday of the so-called `Copen- hagen interpretation' (spanning approximately between 1927 and 1952). The `ortho- dox' approach, generally referred to as `the Copenhagen interpretation', was in fact a mixture of elements borrowed from Heisenberg, Dirac, and von Neumann, with a few words quoted from Bohr and due reverence for his pioneering work, but with no unconditional allegiance to his ideas [Howard2004][Camilleri2009]. Bohr's physical insight was, of course, never overtly put into question. Yet many of his colleagues found his reflections about the epistemological status of theoretical schemes, as well as his considerations on the limits of the representations employed by science, ob- scure and of little practical moment { in a word: too philosophical.1 In addition, it proved somehow uneasy to reach definite conclusions as to the true nature of this philosophy. -

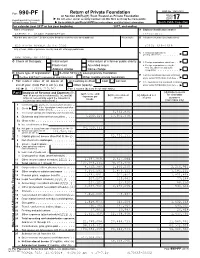

2017 IRS FORM 990-PF.Pdf

OMB No. 1545-0052 Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation I or Section 4947(a)(1) Trust Treated as Private Foundation À¾µ» Do not enter social security numbers on this form as it may be made public. Department of the Treasury I Internal Revenue Service Go to www.irs.gov/Form990PF for instructions and the latest information. Open to Public Inspection For calendar year 2017 or tax year beginning , 2017, and ending , 20 Name of foundation A Employer identification number ALFRED P. SLOAN FOUNDATION 13-1623877 Number and street (or P.O. box number if mail is not delivered to street address) Room/suite B Telephone number (see instructions) 630 FIFTH AVENUE SUITE 2200 (212) 649-1649 City or town, state or province, country, and ZIP or foreign postal code C If exemption applicatmionm ism m m m m m I pending, check here NEW YORK, NY 10111 m m I G Check all that apply: Initial return Initial return of a former public charity D 1. Foreign organizations, check here Final return Amended return 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test, checkm hem rem anmd am ttamchm m m I Address change Name change computation H Check type of organization: X Section 501(c)(3) exempt private foundation E If private foundation status was terminamtedI Section 4947(a)(1) nonexempt charitable trust Other taxable private foundation under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here I Fair market value of all assets at J Accounting method: Cash X Accrual F If the foundation is in a 60-month terminmatIion end of year (from Part II, col. -

Jeffrey A. Barrett Logic and Philosophy of Science University Of

Jeffrey A. Barrett Logic and Philosophy of Science University of California, Irvine Irvine, CA 92697-5100 [email protected] 9 September 2020 Employment 2018{present Chancellor's Professor UC Irvine 2004{2018 Professor Logic and Philosophy of Science, UC Irvine 2014{2018 Professor Philosophy, UC Irvine 1998{2004 Associate Professor Logic and Philosophy of Science, UC Irvine 1998 Associate Professor Philosophy, UC Irvine 1992-98 Assistant Professor Philosophy, UC Irvine 1990-92 Lecturer Columbia College, Columbia University Education 1992 Ph.D. with Distinction Philosophy Columbia University 1991 M.Phil. Philosophy Columbia University 1991 M.A. Philosophy Columbia University 1986 B.A. Physics Brigham Young University Areas of Specialization Philosophy of Physics, Philosophy of Science, Epistemology, Decision Theory, Game Theory, and Logic. Areas of Competence Philosophy of Mathematics, History of Empiricism, and American Pragmatism. Books and Anthologies *B5. Barrett, J. A. (2020) The Conceptual Foundations of Quantum Mechanics, Oxford: Oxford University Press. B4. Barrett, J. A. and P. Byrne (2012) The Everett Interpretation of Quantum Mechanics: Collected Works and Commentary 1955{1980, Princeton University Press. B3. Barrett, J. A. and J. Alexander, eds. (2002) PSA 2000 Volume II, Selected papers from symposium paper sessions of the Philosophy of Science Association meeting in Vancouver, Canada 2{4 November 2000. University of Chicago Press: Chicago. B2. Barrett, J. A. and J. Alexander, eds. (2001) PSA 2000 Volume I, Selected papers from contributed paper sessions of the Philosophy of Science Association meeting in Vancouver, Canada 2{4 November 2000. University of Chicago Press: Chicago. B1. Barrett, J. A. (1999) The Quantum Mechanics of Minds and Worlds, Ox- ford: Oxford University Press. -

1 Naïve Physics and Quantum Mechanics

Naïve Physics and Quantum Mechanics: The Cognitive Bias of Everett’s Many-Worlds Interpretation Andrew SID Lang* and Caleb J Lutz Department of Computing and Mathematics, Oral Roberts University, USA *Address correspondence to this author at the Department of Computing and Mathematics, 7777 S. Lewis Ave., Tulsa, OK, 74171 USA. E-mail: [email protected] Keywords: cognitive bias, Everett’s interpretation, naïve physics, quantum mechanics Abstract: We discuss the role that intuitive theories of physics play in the interpretation of quantum mechanics. We compare and contrast naïve physics with quantum mechanics and argue that quantum mechanics is not just hard to understand but that it is difficult to believe, often appearing magical in nature. Quantum mechanics is often discussed in the context of "quantum weirdness" and quantum entanglement is known as "spooky action at a distance." This spookiness is more than just because quantum mechanics doesn't match everyday experience; it ruffles the feathers of our naïve physics cognitive module. In Everett's many- worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, we preserve a form of deterministic thinking that can alleviate some of the perceived weirdness inherent in other interpretations of quantum mechanics, at the cost of having the universe split into parallel worlds at every quantum measurement. By examining the role cognitive modules play in interpreting quantum mechanics, we conclude that the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics involves a cognitive bias not seen in the Copenhagen interpretation. Introduction Neils Bohr said of quantum mechanics, “Those who are not shocked when they first come across quantum theory cannot possibly have understood it.” [1] When one first learns about quantum mechanics, it appears to be a theory that cannot be describing reality. -

Bacciagaluppi CV

Guido Bacciagaluppi: Curriculum Vitae and List of Publications 1 December 2020 Born Milan (Italy), 24 August 1965. Italian citizen. Freudenthal Instituut Postbus 85.170 3508 AD Utrecht The Netherlands Email: [email protected] Tel.: +31 (0)30 253 5621 Fax: +31 (0)30 253 7494 Web: https://www.uu.nl/staff/GBacciagaluppi/Profile https://www.uu.nl/staff/GBacciagaluppi/Research https://www.uu.nl/staff/GBacciagaluppi/Teaching Research interests My main field of research is the philosophy of physics, in particular the philosophy of quantum theory, where I have worked on a variety of approaches, including modal interpretations (for my PhD), stochastic mechanics, Everett theory, de Broglie-Bohm pilot-wave theory and spontaneous collapse theories, with a special interest in the theory of decoherence. Other special interests include time (a)symmetry, the philosophy of probability, issues in the philosophy of logic, and the topics of emergence, causation, and empiricism. I also work on the history of quantum theory and have co-authored three books on the topic, including a widely admired monograph on the 1927 Solvay conference, and I am a contributor to the recent revival of interest in the figure and work of Grete Hermann. Present positions Academic: • Utrecht University: Associate Professor (UHD1, scale 14), Freudenthal Institute, Departement of Mathematics, Faculty of Science, and Descartes Centre for the History and Philosophy of the Sciences and the Humanities, since September 2015. • SPHERE (CNRS, Paris 7, Paris 1), Paris: Associate Member since April 2015. • Foundational Questions Institute (http://fqxi.org/): Member since February 2015. • Institut d’Histoire et de Philosophie des Sciences et des Techniques (CNRS, Paris 1, ENS), Paris: Associate Member since January 2007. -

Quantum-Theory Wars Reference Frames, of Holding Mutually Opposing Views and of Being Free to Ramin Skibba Explores a History of Unresolved Change One’S Mind

COMMENT BOOKS & ARTS are led away to their doom”. He says what you wouldn’t expect; if Dyson has a pattern, perhaps it is contra- riety. He prefers the students at Haver- ford College, a liberal-arts university in Pennsylvania — who are “ostentatiously ill-dressed, uncombed, and unwashed” — to Princeton’s “pampered” ones. He con- tradicts himself. His wartime job at the UK Royal Air Force’s Bomber Command, analysing the effect of Allied firebomb- ing on German cities, left him “All these with a “perma- adventures in nently bad con- this strange new science”. Yet he world are still understood the unreal to me.” joy of German sailors who torpedoed Allied fuel tankers because he felt “elation” when the fire- bombing succeeded. In the late 1950s, he worked with the defence contractor General Atomic in La Jolla, California, on a project he thought would be “legendary”: a space- ship called Orion, ill-advisedly powered by nuclear explosions. Because building it required nuclear testing, he publicly opposed the Nuclear Test Ban Treaty; after Orion was defunded, he supported the treaty. Later, he became president of the anti-nuclear-proliferation Federation of American Scientists. He proposed the ‘no first use’ policy on nuclear weapons, Niels Bohr (left) with Albert Einstein in the late 1920s, when quantum mechanics was in its infancy. while admiring his theoretical-physicist friend Edward Teller for standing against PHYSICS the treaty. Dyson’s contradictions might seem confusing, but I can hear him politely and methodically explaining the rationality of seeing reality from different Quantum-theory wars reference frames, of holding mutually opposing views and of being free to Ramin Skibba explores a history of unresolved change one’s mind. -

On the Art of Scientific Imagination

On the Art of Scientific Imagination The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Holton, Gerald. 1996. On the Art of Scientific Imagination. Daedalus 125 (2): 183-208. Published Version https://www.jstor.org/stable/20013446? seq=1#metadata_info_tab_contents Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:40508269 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA NOTES FROM THE ACADEMY The text of addresses given at the Stated Meetings of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences are generally printed in the Academy's Bulletin, distributed principally to Fellows and Foreign Honorary Members of the Academy. Because the Bulletin's format is not one designed to accommodate many detailed illustrations, and because the communication delivered by Professor Gerald Holton at the House of the Academy, like others recently given, raised such interest among those who heard it, a decision was made to make it more widely available through publication in the Academy's journal, Dadalus. This practice, followed very occasionally in the past, has much to recommend it and may be pursued more fre quently in the future. [S.R.G.] Gerald Holton On the Art of Scientific Imagination Wver HEN THE ACADEMY S PRESIDENT asked if I would speak on Saint Valentine's Day, I gladly accepted the honor. -

The Most Dangerous Possible German Algis Valiunas

Algis Valiunas David M. Buisán (instagram.com/davidmbuisan) 36 ~ The New Atlantis Copyright 2019. All rights reserved. Print copies available at TheNewAtlantis.com/BackIssues. The Most Dangerous Possible German Algis Valiunas What trace of his earthly passage can a man of genius hope will remain after his death? For a great scientist, it is almost certainly a discovery that advances human understanding a step further from ignorance and con- fusion. To uncover some eternal truth that has been carefully concealed from ordinary sight by Nature or whatever gods there be, and to enjoy the lasting esteem accorded the world-altering thinkers — these are the motive forces behind the most serious and accomplished scientific lives. To one who opens new mental continents for further exploration, and exploitation, the supreme accolades rightly belong. Honor of this order is not a paltry thing. Yet John Milton called the craving for fame “that last infirmity of noble mind”; and while such infirmity might easily be forgiven poets, who are notorious for their moral weakness, we have become accustomed to thinking of scientists as free of such all-too-human frailties. Like Aristotle’s theoretical man in the Nicomachean Ethics, scientists are said to live for the unsurpassed pleasure of knowing the highest things in the universe, those that cannot be other than they are. This makes them god- like, so that they need nothing else — certainly not the glint of admiration or envy in other men’s eyes. And yet perfection is not to be expected even from the most high- minded among us. -

Christopher Alan Fuchs Curriculum Vitae 8 November 2019

Christopher Alan Fuchs Curriculum Vitae 8 November 2019 Personal: Work address: Department of Physics University of Massachusetts Boston 100 Morrissey Boulevard Boston, Massachusetts 02125 Internet: [email protected] http://www.physics.umb.edu/Research/QBism/ http://scholar.google.com/citations?user=fe9uXzkAAAAJ Research Interests: Quantum foundations in the light of quantum information Quantum information theory Professional Positions (beyond postdoctoral level): Professor of Physics, University of Massachusetts Boston, 2015{ Research Fellow, Max Planck Institute for Quantum Optics, Garching, Germany, 2014 Senior Scientist, Raytheon BBN Technologies, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 2013{2014 Senior Researcher, Perimeter Institute for Theoretical Physics, Waterloo, Canada, 2007{2013 Member of Technical Staff, Bell Laboratories, Alcatel-Lucent, Murray Hill, New Jersey, 2000{2007 Education: Ph. D. in Physics, May 1996, The University of New Mexico, Albuquerque, New Mexico Dissertation: \Distinguishability and Accessible Information in Quantum Theory" Advisor: Carlton M. Caves B. S. in Physics with High Honors, December 1987 B. S. in Mathematics with High Honors, December 1987 The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, Texas Research Supervisor: John Archibald Wheeler Titles, Honors, Awards, Marks of Distinction: Fellow of the American Physical Society. Elected 2012, \for powerful theorems and lucid expositions" that culminated in the view of quantum theory known as QBism. International Quantum Communication Award, 2010, citation: \for contributions to the theory of quan- tum communication including quantum state disturbance." Lee A. DuBridge Prize Postdoctoral Fellowship, California Institute of Technology, Pasadena, California, 1996{1999. Paper A45 was listed among the \top ten breakthroughs of the year 1998" by the editors of Science. The Web of Science Citation Index gives a citation count of ≥ 6; 200, with a Hirsch index h = 31 and an average of 117/paper, on the 54 journal articles it lists for me. -

The Early Period Klaus Scharnhorst

Photon-photon scattering and related phenomena. Experimental and theoretical approaches: The early period Klaus Scharnhorst To cite this version: Klaus Scharnhorst. Photon-photon scattering and related phenomena. Experimental and theoretical approaches: The early period. 2020. hal-01638181v4 HAL Id: hal-01638181 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01638181v4 Preprint submitted on 30 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. hhal-01638181i Photon-photon scattering and related phenomena. Experimental and theoretical approaches: The early period K. Scharnhorst† Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, Faculty of Sciences, Department of Physics and Astronomy, De Boelelaan 1081, 1081 HV Amsterdam, The Netherlands Abstract We review the literature on possible violations of the superposition prin- ciple for electromagnetic fields in vacuum from the earliest studies until the emergence of renormalized QED at the end of the 1940’s. The exposition covers experimental work on photon-photon scattering and the propagation of light in external electromagnetic fields and relevant theoretical work on non- linear electrodynamic theories (Born-Infeld theory and QED) until the year 1949. To enrich the picture, pieces of reminiscences from a number of (the- oretical) physicists on their work in this field are collected and included or appended.