Subnational Governments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Searching for a New Constitutional Model for East-Central Europe

The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law CUA Law Scholarship Repository Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions Faculty Scholarship 1991 Searching for a New Constitutional Model for East-Central Europe Rett R. Ludwikowski The Catholic University of America, Columbus School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.edu/scholar Part of the Comparative and Foreign Law Commons, and the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Rett. R. Ludwikowski, Searching for a New Constitutional Model for East-Central Europe, 17 SYRACUSE J. INT’L L. & COM. 91 (1991). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at CUA Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Scholarly Articles and Other Contributions by an authorized administrator of CUA Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. SEARCHING FOR A NEW CONSTITUTIONAL MODEL FOR EAST-CENTRAL EUROPE Rett R. Ludwikowski* TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ........................................ 92 II. CONSTITUTIONAL TRADITIONS: THE OVERVIEW ....... 93 A. Polish Constitutional Traditions .................... 93 1. The Constitution of May 3, 1791 ............... 94 2. Polish Constitutions in the Period of the Partitions ...................................... 96 3. Constitutions of the Restored Polish State After World War 1 (1918-1939) ...................... 100 B. Soviet Constitutions ................................ 102 1. Constitutional Legacy of Tsarist Russia ......... 102 2. The Soviet Revolutionary Constitution of 1918.. 104 3. The First Post-Revolutionary Constitution of 1924 ........................................... 107 4. The Stalin Constitution of 1936 ................ 109 5. The Post-Stalinist Constitution of 1977 ......... 112 C. Outline of the Constitutional History of Romania, Bulgaria, Czechoslovakia and Hungary ............. 114 III. CONSTITUTIONAL LEGACY: CONFRONTATION OF EAST AND W EST ............................................ -

The New Energy System in the Mexican Constitution

The New Energy System in the Mexican Constitution José Ramón Cossío Díaz, Supreme Court Justice of Mexico José Ramón Cossío Barragán, Lawyer Prepared for the study, “The Rule of Law and Mexico’s Energy Reform/Estado de Derecho y Reforma Energética en México,” directed by the Baker Institute Mexico Center at Rice University and the Center for U.S. and Mexican Law at the University of Houston Law Center, in association with the School of Government and Public Transformation at the Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Monterrey, the Centro de Investigación para el Desarrollo A.C. (CIDAC), and the Faculty of Law and Criminology at the Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León. © 2017 by the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy of Rice University This material may be quoted or reproduced without prior permission, provided appropriate credit is given to the author and the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy. Wherever feasible, papers are reviewed by outside experts before they are released. However, the research and views expressed in this paper are those of the individual researcher(s) and do not necessarily represent the views of the James A. Baker III Institute for Public Policy. José Ramón Cossío Díaz José Ramón Cossío Barragán “The New Energy System in the Mexican Constitution” The New Energy System in the Mexican Constitution Study Acknowledgements A project of this magnitude and complexity is by necessity the product of many people, some visible and others invisible. We would like to thank Stephen P. Zamora of the University of Houston Law Center and Erika de la Garza of the Baker Institute Latin America Initiative in helping to conceive this project from the start. -

Declaration of the Vii Forum of the Parliamentary Front Against Hunger in Latin America and the Caribbean - Mexico City

DECLARATION OF THE VII FORUM OF THE PARLIAMENTARY FRONT AGAINST HUNGER IN LATIN AMERICA AND THE CARIBBEAN - MEXICO CITY We, Members of the Parliaments and members of the Latin America and the Caribbean Parliamentary Front against Hunger (PFH), with the valuable participation of parliamentarians from Africa and Europe, gathered in 1 Mexico City on November 9, 10 and 11, 2016, on the occasion of the 7th Forum of the Parliamentary Front against Hunger in Latin America and the Caribbean. CONSIDERING That the agenda of the States set the focus on the fight against hunger and malnutrition and on the food sovereignty of the nations, as it is stated in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development and in its Goal 2 “End hunger, achieve food security and improved nutrition and promote sustainable agriculture,” as well as in the Paris Agreement on Climate Change, which came into force on November 4th, 2016; also, considering that in the Latin America and the Caribbean parliaments, laws on food and nutrition security and sovereignty have been approved and are under discussion. That in the above-mentioned Agenda the legislative powers are crucial agents to end hunger and malnutrition, as it is reflected in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, when noting that the Members of the Parliaments perform a key role in the achievement of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) by “enacting legislation, approving budgets, and ensuring accountability”. That in the Special Declaration on the “Plan for Food Security, Nutrition and Hunger Eradication” of January 27, 2016, announced on the occasion of the IV Latin America and the Caribbean States Summit (CELAC) held in Quito, Ecuador, the Heads of State and Government of the region reaffirmed their commitment to the eradication of hunger and malnutrition, as an essential element in order to achieve sustainable development. -

Comparing Power— an Appraisal of Comparative Government and Politics AP Comparative and Politics Curriculum 2 Teachers 2019

Citizen U Presents: Comparing Power— An Appraisal of Comparative Government and Politics AP Comparative and Politics Curriculum 2 Teachers 2019 Big Ideas in AP Comparative Government and Politics* 1. POWER AND AUTHORITY (PAU)* 2. LEGITIMACY AND STABILTY (LEG)* 3. DEMOCRATIZATION (DEM)* 4. INTERNAL/EXTERNAL FORCES (IEF)* 5. METHODS of POLITICAL ANALYSIS (MPA)* Unit 1: Political Systems, Regimes, and Governments* MPA— Enduring Understanding: Empirical data is important in identifying and explaining political behavior of individuals and groups.* 1.1 Explain how political scientists construct knowledge and communicate inferences and explanations about political systems, institutional interactions, and behavior* Analysis of quantitative and qualitative information (including charts, tables, graphs, speeches, foundational documents, political cartoons, maps, and political commentaries) is a way to make comparisons between and inferences about course countries.* Analyzing empirical data using quantitative methods facilitates making comparisons among and inferences about course countries.* One practice of political scientists is to use empirical data to identify and explain political behavior of individuals and groups. Empirical data is information from observation or experimentation. By using empirical data, political scientists can construct knowledge and communicate inferences and explanations about political systems, institutional interactions, and behavior. Empirical data such as statistics from sources such as governmental reports, polls, -

CONSTI INGLES SEPT 2010.Pdf

First edition: August 2005 Second edition: November 2008 Third edition: March 2010 Fourth edition: August 2010 All rights reserved. © Mexican Supreme Court Av. José María Pino Suárez, No. 2 C.P. 06065, México, D.F. Printed in Mexico Translators: Dr. José Antonio Caballero Juárez and Lic. Laura Martín del Campo Steta. Translation updated by: Lic. Sergio Alonso Rodríguez Narváez and Estefanía Vela The update, edition, and design of this publication was made by the General Management of the Coordination on Compilation and Systematization of Theses of the Mexican Supreme Court. Mexican Supreme Court Justice Guillermo I. Ortiz Mayagoitia President First Chamber Justice José de Jesús Gudiño Pelayo President Justice José Ramón Cossío Díaz Justice Olga María Sánchez Cordero de García Villegas Justice Juan N. Silva Meza Justice Arturo Zaldívar Lelo de Larrea Second Chamber Justice Sergio Salvador Aguirre Anguiano President Justice Luis María Aguilar Morales Justice José Fernando Franco González Salas Justice Margarita Beatriz Luna Ramos Justice Sergio A. Valls Hernández Publications, Social Communication, Cultural Diffusion and Institutional Relations Committee Justice Guillermo I. Ortiz Mayagoitia Justice Sergio A. Valls Hernández Justice Arturo Zaldívar Lelo de Larrea Editorial Committee Mtro. Alfonso Oñate Laborde Technical Legal Secretary Mtra. Cielito Bolívar Galindo General Director of the Theses Compilation and Systematization Bureau Lic. Gustavo Addad Santiago General Director of Diffusion Judge Juan José Franco Luna General Director of the Houses of Juridical Culture and Historical Studies Dr. Salvador Cárdenas Gutiérrez Director of Historical Research CONTENT FOREWORD ................................... IX TITLE ONE CHAPTER ONE Fundamental rights ............................................1 CHAPTER TWO Mexican nationals ............................................ 95 CHAPTER THREE Aliens ................................................................ 99 CHAPTER FOUR Mexican citizens ............................................ -

![Downloaded from the Mexico’Sgeneral and Risks in Both Sides of the Border [6], but Population Directorate on Health Information (DGIS) [12]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3269/downloaded-from-the-mexico-sgeneral-and-risks-in-both-sides-of-the-border-6-but-population-directorate-on-health-information-dgis-12-1013269.webp)

Downloaded from the Mexico’Sgeneral and Risks in Both Sides of the Border [6], but Population Directorate on Health Information (DGIS) [12]

Anaya and Al-Delaimy BMC Public Health (2017) 17:400 DOI 10.1186/s12889-017-4332-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Effect of the US-Mexico border region in cardiovascular mortality: ecological time trend analysis of Mexican border and non- border municipalities from 1998 to 2012 Gabriel Anaya* and Wael K Al-Delaimy Abstract Background: An array of risk factors has been associated with cardiovascular diseases, and developing nations are becoming disproportionately affected by such diseases. Cardiovascular diseases have been reported to be highly prevalent in the Mexican population, but local mortality data is poor. The Mexican side of the US-Mexico border has a culture that is closely related to a developed nation and therefore may share the same risk factors of cardiovascular diseases. We wanted to explore if there was higher cardiovascular mortality in the border region of Mexico compared to the rest of the nation. Methods: We conducted a population based cross-sectional time series analysis to estimate the effects of education, insurance and municipal size in Mexican border (n = 38) and non-border municipalities (n = 2360) and its association with cardiovascular age-adjusted mortality rates between the years 1998–2012. We used a mixed effect linear model with random effect estimation and repeated measurements to compare the main outcome variable (mortality rate), the covariates (education, insurance and population size) and the geographic delimiter (border/non-border). Results: Mortality due to cardiovascular disease was consistently higher in the municipalities along the US-Mexico border, showing a difference of 78 · 5 (95% CI 58 · 7-98 · 3, p < 0 · 001) more cardiovascular deaths after adjusting for covariates. -

Municipality-Level Predictors of COVID-19 Mortality in Mexico: a Cautionary Tale Alejandra Contreras-Manzano Scd1, Carlos M

Disaster Medicine and Public Health Preparedness Municipality-Level Predictors of COVID-19 Mortality in Mexico: A Cautionary Tale www.cambridge.org/dmp Alejandra Contreras-Manzano ScD1, Carlos M. Guerrero-L´opez MSc2, Mercedes Aguerrebere MD, MSc3, Ana Cristina Sedas MD, MSc4 and Héctor Lamadrid-Figueroa MD, ScD5 Original Research 1 Cite this article: Contreras-Manzano A, Center for Nutrition and Health Research, National Institute of Public Health, Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico; 2 3 Guerrero-L´opez CM, Aguerrebere M, Sedas AC, Mexican Social Security Institute, Juárez, Cuauhtémoc, Mexico; National Autonomous University of Mexico, 4 Lamadrid-Figueroa H. Municipality-level Mexico City, Mexico; Department of Global Health and Social Medicine, Harvard Medical School, Boston, predictors of COVID-19 mortality in Mexico: A Massachusetts USA and 5Center for Population Health Research, National Institute of Public Health, cautionary tale. Disaster Med Public Health Cuernavaca, Morelos, Mexico Prep. doi: https://doi.org/10.1017/ dmp.2020.485. Abstract Keywords: Objective: Local characteristics of populations have been associated with coronavirus disease COVID-19; risk factors; social determinants; 2019 (COVID-19) outcomes. We analyze the municipality-level factors associated with a high health determinants; municipality-level COVID-19 mortality rate (MR) of in Mexico. Corresponding author: Methods: We retrieved information from cumulative confirmed symptomatic cases and deaths Héctor Lamadrid-Figueroa, from COVID-19 as of June 20, 2020, and data from most recent census and surveys of Mexico. Email: [email protected]. A negative binomial regression model was adjusted, the dependent variable was the number of COVID-19 deaths, and the independent variables were the quintiles of the distribution of sociodemographic and health characteristics among the 2457 municipalities of Mexico. -

U.S. Immigration Enforcement and Mexican Labor Markets

U.S. Immigration Enforcement and Mexican Labor Markets Thomas Pearson ∗ PhD Student Department of Economics Boston University Abstract This paper uses Secure Communities (SC), a policy which expanded local immigration enforcement, to study how increased immigration enforcement in the US affects Mexican labor markets. The variation in the application of SC across US states and in the destination patterns of comparably similar Mexican municipalities generates quasi-random variation in exposure to the policy. I show that in the short run, exposure to SC deportations increases return migration and decreases monthly incomes from working for less-educated men and women. SC deportations also increase net outflows within Mexico and emigration to the US, a potential mechanism for why earnings mostly rebound after five years. The negative short run effects do not appear to be driven by falls in remittance income or increases in crime as SC deportations increase the share of households receiving remittances and do not affect homicide rates. The results instead point to increased labor market competition as a result of deportee inflows. Lastly, I show that in municipalities with more banks and access to capital and where transportation and migration costs are lower, men's earnings are less responsive to the labor supply shock. Keywords: Return migration, deportations, labor markets JEL Codes: F22, O15, J40, R23 ∗270 Bay State Rd., Boston, MA 02215. Phone: 1-317-997-4495. Email: [email protected] 1 Introduction Since Congress passed the Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act (IIRIRA) in 1996, the US has deported a record number of unauthorized immigrants and other removable noncitizens (Rosenblum and Meissner 2014). -

Mexican Elections in 2018

Mexican elections in 2018: What to expect when you're expecting? . The upcoming electoral process of 2018 in Mexico is one of the September 15, 2017 geopolitical risks to the outlook www.banorte.com . We believe that it is still too early to call the electoral result www.ixe.com.mx @analisis_fundam . In fact, polls still show a high degree of indecision among the population Delia Paredes . We expect a tight race, albeit with a limited impact on the Executive Director of Economic Analysis markets [email protected] . This election is particularly important since it will be one of the first times many of the new laws enacted as part of 2014’s electoral reform will be carried out, although some will come into effect later: (1) Senators and Representatives elected in 2018 might be reelected; (2) Possibility of coalition governments and independent candidates; (3) Changes in the regime of political parties; (4) New provisions for the National Electoral Institute (INE); and (5) Provisions regarding popular consultations . There are mechanisms established in case of a contested election . In addition, at the end of this year there are also two important processes: (1) The transition of power in Banxico; and (2) 2018’s budget process Mexican elections in 2018 What to expect when you're expecting? The electoral process in Mexico is one of the geopolitical risks for the scenario of the coming year. After the delivery of the 2018 fiscal budget on September 8th, the 2018 electoral process will now be the center of attention with parties already taking some steps in this direction. -

The Value of TRUTH a Third of the Way

The value of TRUTH A third of the way MARCH 2021 THE VALUE OF TRUTH :: 1 https://www.elmundo.es/america/2013/01/08/mexico/1357679051html Is a non-profit, non governmental organization thats is structured by a Council built up of people with an outstanding track record, with high ethical and pro- fessional level, which have national and international recognition and with a firm commitment to democratic and freedom principles. The Council is structured with an Executive Committee, and Advisory Committee of Specialists and a Comunication Advisory Committee, and a Executive Director coordinates the operation of these three Committees. One of the main objectives is the collection of reliable and independent informa- tion on the key variables of our economic, political and sociocultural context in order to diagnose, with a good degree of certainty, the state where the country is located. Vital Signs intends to serve as a light to show the direction that Mexico is taking through the dissemination of quarterly reports, with a national and international scope, to alert society and the policy makers of the wide variety of problems that require special attention. Weak or absent pulse can have many causes and represents a medical emergency. The more frequent causes are the heart attack and the shock condition. Heart attack occurs when the heart stops beating. The shock condition occurs when the organism suffers a considerable deterioration, wich causes a weak pulse, fast heartbeat, shallow, breathing and loss of consciousness. It can be caused by different factors. Vital Signs weaken and you have to be constantly taking the pulse. -

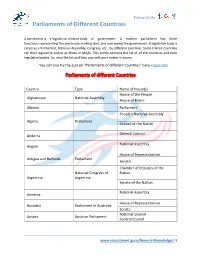

Parliaments of Different Countries

Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries A parliament is a legislative, elected body of government. A modern parliament has three functions: representing the electorate, making laws, and overseeing the government. A legislative body is called as a Parliament, National Assembly, Congress, etc., by different countries. Some Islamic countries call their legislative bodies as Shora or Majlis. This article contains the list of all the countries and their legislative bodies. So, read the list and help yourself score better in exams. You can also try the quiz on “Parliaments of different Countries” here – Quiz Link Parliaments of different Countries Country Type Name of house(s) House of the People Afghanistan National Assembly House of Elders Albania Parliament People's National Assembly Algeria Parliament Council of the Nation General Council Andorra National Assembly Angola House of Representatives Antigua and Barbuda Parliament Senate Chamber of Deputies of the National Congress of Nation Argentina Argentina Senate of the Nation National Assembly Armenia House of Representatives Australia Parliament of Australia Senate National Council Austria Austrian Parliament Federal Council www.recruitment.guru/General-Knowledge/|1 Follow Us On Parliaments of Different Countries Azerbaijan National Assembly House of Assembly Bahamas, The Parliament Senate Council of Representatives Bahrain National Assembly Consultative Council National Parliament Bangladesh House of Assembly Barbados Parliament Senate House of Representatives National Assembly -

European Union Election Observation Mission Mexico 2006 FINAL REPORT

Final Report European Union Election Observation Mission Mexico 2006 FINAL REPORT This report was produced by the EU Election Observation Mission and presents the EU EOM’s findings on the 2006 Presidential and Parliamentary elections in Mexico. These views have not been adopted or in any way approved by the Commission and should not be relied upon as a statement of the Commission. The European Commission does not guarantee the accuracy of the data included in this report, nor does it accept responsibility for any use made thereof. M E X I C O FINAL REPORT PRESIDENTIAL AND PARLIAMENTARY ELECTIONS 2 July 2006 EUROPEAN UNION ELECTION OBSERVATION MISSION 23 November 2006, Mexico City/Brussels TABLE OF CONTENT I. EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1 II. INTRODUCTION 4 III. POLITICAL BACKGROUNG 5 A. Political Context 5 B. The Political Parties and Candidates 7 IV. LEGAL ISSUES 9 A. Political Organization of Mexico 9 B. Constitutional and Legal Framework 10 V. ELECTION ADMINISTRATION 11 A. Structure of the Election Administration 11 B. Performance of IFE 12 C. The General Council 13 VI. VOTER REGISTRATION 14 VII. REGISTRATION OF NATIONAL POLITICAL PARTIES 16 VIII. CANDIDATE REGISTRATION 17 IX. VOTING BY MEXICANS LIVING ABROAD 18 X. PARTICIPATION OF INDIGENOUS PEOPLE 19 XI. THE ‘CASILLAS ESPECIALES’ 20 XII. CIVIC AND VOTER EDUCATION 22 XIII. ELECTION CAMPAIGN 22 A. Campaign Environment and Conditions 22 B. Use of State Resources 23 C. Financing of Political Parties 25 D. Campaign Financing 26 XIV. PARTICIPATION OF CIVIL SOCIETY AND OBSERVATION 28 XV. MEDIA 29 A. Freedom of the Press 30 B. Legal Framework 31 C.