Elsaifi, 1 Edward F. Mitchusson, Doctor, Soldier, and Relative When

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cora Carleton) Papers, 1862-1958

Texas A&M University-San Antonio Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection Archives & Special Collections 2020 Glassford (Cora Carleton) Papers, 1862-1958 DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids Cora Carleton Glassford Papers, 1862-1958 Descriptive Summary Creator: Glassford, Cora Carleton (1886-1958) Title: Cora Carleton Glassford Papers Dates: 1862-1958 Creator Cora Carleton Glassford was active in a number of organizations, Abstract: including the Daughters of the Republic of Texas, and devoted her time to writing fiction, historical articles, and biographical works, much of it based on personal experience. Content Consisting of manuscripts, research material, and some personal Abstract: material, the Cora Carleton Glassford papers reflect a lifelong interest in history and family. Identification: Col 892 Extent: 17 document boxes, 2 oversize boxes Language: Materials are in English Repository: DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Biographical Note Born on the campus of Texas A&M College in 1886, Cora Arthur Carleton was the first child of career Army officer Guy Carleton and his wife Cora. Accompanying her family to most of the postings of her father's military career, she spent her childhood in Arizona, New Mexico, Minnesota, Kansas, Texas, the Philippines and China. Her military association would continue in adulthood, when she met and married another Army officer, Pelham Davis Glassford (1883-1959) while at Fort Riley, Kansas. Her travels also continued as she accompanied her husband to assignments at the U.S. Military Academy, Hawaii, Texas, Kansas and Washington, D.C. -

Buri~I 'Llreasu1a

Buri~i 'llreasu1a Volume 32 Number 2: April - June 2000 Central Florida Genealogical Society, Inc. ---~ - --- Buried Treasures Central Florida Genealogical Society, Inc. - P. 0 . Box 536309, Orlan1do, FL 32853-6309 Web Site: http://www.geocities.com/Heartland!Rancb/4580 Editor: Betty Jo Stockton (407) 876-1688 Email: [email protected] Volume32 April- June 2000 No.2 The Central Florida Genealogical Society, Inc. meets monthly, September through May. Meetings are held at the Marks Street Senior Center Auditorium on the second Thursday of eac:h month at 7:30P.M. Marks Street Center is located at 99 E. Marks Street (at the comer of Marks and Magnolia) near downtown Orlando. The Board meets year-round on the third Tuesday of each month at the Orlando Public Library. All are welcome to attend. Table d O>ntent!• The President Says... n Some Thoughts from your Editor . u A Story of William Hatcher "the Immigrant" and his descendants .................... 23 National Archives proposes change to fee schedule . 25 The men who fell at the Alamo - 6 March 1836 . 26 World's Largest Known Family Tree ............................. ... ........... 28 1816: The year without a summer ................. ..... .. .... ................ 28 State Census- 1885 Orange County, Florida ............................. .... 29 Book Review: In Memoriam . 33 A Bit about St Cloud, Florida . 33 Eulogy of Robert Roberts (1842- 1912) ....................... ................. 34 Biographical Sketch of Robert Roberts. 34 Travels Through The War By Robert Roberts . 36 Remembering Early Days in Longwood as told by Alice (Bryant) Coleman . 38 Descendants ofEli Warren Burkett of Orange and Seminole Counties, FL .............. 40 Wanted! Natives and Original Families of Seminole County, Florida ............... -

Schedule Company of Military Historians Meeting San Antonio

Schedule Company of Military Historians Meeting San Antonio, Texas 23 March to 26 March 2017 Thursday March 23 Optional Trip to AMEDD and Fort Sam Houston Museums (AM), and USAF Museum of Basic Training and Security Police Museums (PM). Box lunch provided. Limited to 50 people. Registration and message center open (1100) Flea market/exhibit room set-up (1100 Opening Reception, Menger Hotel (1800) Friday March 24 Registration and message center open Flea market/exhibit room open Company Meeting (0830 – 0930), Craig Bell Break (0930 – 1000) Lecture 1 (1000 – 1100) Session A: Aggie Fashion: A Century of Cadet Uniforms at Texas A&M, Walter Bradford Session B: Preservation and Conservation of Artifacts, Chris Semancik and James Speraw, Center of Military History Field trip: Museum of the South Pacific War (1 hr travel). Box lunch provided to eat on bus to Fredericksburg, TX. Saturday March 25 Lecture 2 (0830 – 0930) Session C: Oklahoma Rough Riders: Richard Killblane Session D: British Artillery: W. Sanders Marble, PhD Break (0930 – 1000) Lecture 3 (1000 – 1100) Session E: Mobilizing the Texas Guard for World War I: Greg Ball, PhD Session F: The myths about the Battle of the Alamo, Stephen Hardin, PhD Lecture 4 (1100 – 1200) Session G: Dr. Amos Pollard, Chief Surgeon of the Alamo Garrison, 1836, Scott Woodard Session H: Houston Riots: Isaac Hampton, PhD Lunch on your Own (1200 – 1300) Field Trip: The Alamo, includes orientation presentation, (1300 - 1700) Orientation: 1300-1400 Guided Tour of Alamo: 1400-1700 Cocktail reception (1830) Banquet & awards ceremony (1930) Sunday March 26 Remove and clear flea market/exhibit Hotel check out On your own trip to Goliad and San Jacinto. -

Alamo Primary Sources

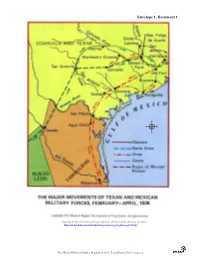

Envelope 1, Document 1 Courtesy of the University of Texas Libraries, The University of Texas at Austin http://www.lib.utexas.edu/maps/atlas_texas/tex_mex_forces_1836.jpg Fort Worth ISD Social Studies Department 2013, Texas History Unit 5 resources Envelope 1, Document 2 Map of the Alamo showing the "Ground plan compiled from drawings by Capt. B. Green Jameson, Texan Army, January, 1826,Col. Ignacio de Labastida, Mexican Army, March, 1836, Capt. Ruben M. Potter, United States Army, 1841." http://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth30285/m1/1/ Fort Worth ISD Social Studies Department 2013, Texas History Unit 5 resources http://www.latinamericanstudies.org/texas-maps-1.htm Envelope 2, Document 3 Fort Worth ISD Social Studies Department 2013, Texas History Unit 5 resources Defenders of the Alamo - http://www.thealamo.org/history/the-1836-battle/the-defenders/index.html Envelope 2, Document 4 Juan Abamillo, San Antonio James W. Garrand, La. James Nowlan, Ireland R. Allen James Girard Garrett, Tenn. George Pagan, Miss. Mills DeForrest Andross, Vermont John E. Garvin Christopher Parker, Miss. Micajah Autry, N.C. John E. Gaston. Ky. William Parks, N.C. Juan A. Badillo, San Antonio James George Richardson Perry Peter James Bailey, Ky. John Camp Goodrich, Tenn. Amos Pollard, Mass. Isaac G. Baker, Ark. Albert Calvin Grimes, Ga. John Purdy Reynolds, Pa. William Charles M. Baker, Mo. Jose Maria Guerrero, Laredo, Tex. Thomas H. Roberts John J. Ballentine James C. Gwynne, England James Robertson, Tenn. Richard W. Ballantine, Scotland James Hannum Isaac Robinson, Scotland John J. Baugh, Va John Harris, Ky. James M. Rose, Va. -

Swearingen 18 Notes United St

Texas ( \ 1821 - 1845 Moses Austin 1. From Connecticut: A) 1st American - Idea - Anglo colonization of Texas by Americans. 2. December 23, 1821 - Arrives at San Antonio de Bejar in Texas: A) Announces - He desires to settle himself and 300 Families on Spanish soil. 3. January 17, 1821 - Agustin I - Grants Austin's petition. 4. June 1821 - Return trip from Texas: A) Austin dies. B) Last request••• Son, Stephen, complete the colonization. Stephen Fuller Austin 1. Son of Moses Austin. 2. Born - 11/3/1793 - Virginia. 3. Deliberate - Tactful - Diplomatic. 4. Quiet - Energetic - Methodical. 5. Well Educated. 6. Experienced in Public Service. 7. Experienced in Business. 8. Serves••• Missouri Legislature. 9. Circuit Judge in Arkansas. 10. Later••• : · ( A) Defeated for the Presidency of the Republic of Texas by Sam Houston. 11. Later••• : A) Secretary of State for the Republic of Texas. 12. Later••• : A) 12/27/1836 - At age 44. B) Cot - 2 room shack - Penniless - Dies. 13. Later••• : A) Capitol of state of Texas is named after him. 14. At age 27 - Leaves New Orleans with 10 men: A) Inspects Texas. B) Is well received by the Mexicans. C) Returns to New Orleans. ~ ( Decel11ber 1821 1. Austin leads a party overland to Texas. 2. On the Brazos River: A) Establishes the 1st Anglo Settlement in Texas. 3. Austin travels to Mexico City: A) To insure permission to establish his Colony: I. Waits 9 months in Mexico City! ~anuary 1823 1. Mexico passes The Colonization Law. 2. April 14, 1823 - Confirmation is given to Austin: A) His settlers must abide by the Colonization Law. -

Book Reviews

East Texas Historical Journal Volume 37 Issue 2 Article 14 10-1999 Book Reviews Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj Part of the United States History Commons Tell us how this article helped you. Recommended Citation (1999) "Book Reviews," East Texas Historical Journal: Vol. 37 : Iss. 2 , Article 14. Available at: https://scholarworks.sfasu.edu/ethj/vol37/iss2/14 This Book Review is brought to you for free and open access by the History at SFA ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in East Texas Historical Journal by an authorized editor of SFA ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. EAST TEXAS HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION 81 BOOK REVIEWS The Explurers' Texas: The Animals They Found, Vol II, Del Weniger (Eakin Press, P.O, Box 90159, Austin, TX 78709-0159) 1997. B&W Photos. Maps. Bibliography. Notes. P. 200. $27.95. Hardcover. Del Weniger, professor emeritus of biology at Our Lady of the Lake University, San Antonio, has researched Texas wildlife in the field and in literature for the past fifty years. This volume of The Explorers' Texas is based on his research in the early literature and the historical records of the first Europeans who began coming to Texas in the sixteenth century and continued until they had populated the state in the nineteenth century. Weniger's purpose in The Animals They Found is to describe what the early Texas explorers saw on their travels, when the animal populations were in their pristine states, before Texans began to plow and plant. What these first explorers of Texas saw was the prairies of Texas covered with vast herds of animals - like the teeming plains of the Serengeti in African wildlife films. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E269 HON. LYNN A. WESTMORELAND HON. TED

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E269 to discourage unauthorized workers from en- I am besieged by a thousand or more of the Illinois: Jonathan L. Lindley. tering this country illegally to seek work. En- enemy under Santa Anna. I have sustained a Kentucky: Peter James Bailey III, James suring a legal workforce must be a key com- continual bombardment and cannon fire for Bowie, Daniel William Cloud, Jacob C. Darst, over 24 hours, but I have not lost a man. John Davis, William H. Fauntleroy, John E. ponent of any immigration bill moving through The enemy has demanded surrender at its Gaston, John Harris, William Daniel Jack- Congress. discretion. Otherwise, the fort will be put to son, Green B. Jameson, John Benjamin Kel- I look forward to working with my colleagues the sword. I have answered that demand with logg, Andrew Kent, Joseph Rutherford, B. to build on this proposal to achieve a bipar- a cannon shot. And the flag still waves Archer M. Thomas, Joseph G. Washington. tisan solution to immigration reform. proudly over the north wall. Louisiana: Charles Despallier, James W. I shall never surrender or retreat. I call Garrand, Joseph Kerr, Isaac Ryan. f upon you, in the name of liberty and patriot- Maryland: Charles S. Smith. HONORING BROOKE EDWARDS ism and everything dear to the American Massachusetts: John Flanders, William D. character, to come to my aid with all dis- Howell, William Linn, Amos Pollard. patch. If this call is neglected, I am deter- Mississippi: M.B. Clark, Isaac Millsaps, HON. LYNN A. WESTMORELAND mined to sustain myself for as long as pos- Willis A. -

ABSTRACT JAMES W. FANNIN JR.: a BIOGRAPHY Michelle E. Herbelin

ABSTRACT JAMES W. FANNIN JR.: A BIOGRAPHY Michelle E. Herbelin Director: T. Michael Parrish, Ph.D. This thesis is a biography of Colonel James W. Fannin Jr., a pivotal and controversial but often marginalized figure in the Texas Revolution. Showing brilliant potential in the 1835 campaign, he was later caught up in the midst of a constitutional crisis in the Texas Provisional Government. He struggled to reckon with conflicting duties and unrealistic expectations in the face of the rapidly advancing Mexican Army. Fannin did not live to see the outcome of the Revolution, meeting his death in a bloody episode known commonly to Texas historiography as the Goliad Massacre. This study makes use of Fannin’s own frank, often introspective correspondence, accounts from the survivors of his command, and even more heretofore unutilized sources, and endeavors to describe Fannin in his rightful historical context: as an American, Southerner, and Texian. APPROVED BY DIRECTOR OF HONORS THESIS ____________________________________________________ Dr. Michael Parrish, Department of History APPROVED BY THE HONORS PROGRAM: ________________________________________________ DATE:_______________________ JAMES W. FANNIN JR.: A BIOGRAPHY A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of Baylor University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Honors Program By Michelle E. Herbelin Waco, Texas May 2015 TABLE OF CONTENTS Dedication . iii Introduction . iv Chapter One: From Georgia to Texas, 1805 to 1834 . 1 Chapter Two: The Coming of War and Military Apprenticeship, August 1835 to January 1836 . 23 Chapter Three: Agent of the Provisional Government: The Matamoros Expedition . 44 Chapter Four: The Friction and Fog of War: At Goliad, February-March 1836 61 Chapter Five: The Final Campaign: March 1836. -

Fiesta San Antonio Collection, 1897-2007

Texas A&M University-San Antonio Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection Archives & Special Collections 2020 Fiesta San Antonio Collection, 1897-2007 DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids A Guide to the Fiesta San Antonio Collection, 1897-2007 Descriptive Summary Title: Fiesta San Antonio Collection Dates: 1897-2007 Creator Fiesta San Antonio originated with an 1891 celebration staged to Abstract: commemorate events of the Texas Revolution. A parade, which became the annual Battle of Flowers parade, was joined in following years by other events, under several organizations. The overall celebration became Fiesta San Jacinto, under the Fiesta San Jacinto Association. The name was changed under a reorganization in 1959, placing the event under a new umbrella entity, the Fiesta San Antonio Commission. Content The Fiesta San Antonio collection gathers material from various Abstract: sources, all related to the annual San Antonio, Texas, celebration. Included are invitations, programs, clippings, other printed material, and artifacts. Identification: DRT 3 Extent: 7.5 linear feet (2 document boxes, 3 oversize boxes) Language: Materials are in English. Repository: DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Historical Note Fiesta San Antonio had its origins in an 1891 celebration staged to commemorate the events of the Texas Revolution, particularly the Battle of San Jacinto. The first event consisted of a parade and flower battle, which became the annual Battle of Flowers parade. A number of organizations formed over time to manage portions of the event, including the Battle of Flowers Association, which oversees the parade; the Order of the Alamo, which selects and stages the coronation of Fiesta royalty; and the Texas Cavaliers, which selects a Fiesta King and stages the River Parade. -

2899 Hon. Raúl M. Grijalva Hon. Nick J. Rahall Ii

February 28, 2008 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS, Vol. 154, Pt. 2 2899 The youngest to die for Texas was 15-year-old Daymon, William Dearduff, Almeron Corps is forever linked in American hearts to William Phillip King. The oldest to die was Dickerson (Dickinson), John Henry Dillard, the spirit of those one-thousand days that Gordon C. Jennings. He was 56. Their sac- James L. Ewing, James Girard Garret, An- were inaugurated with the words, ‘‘my fellow drew Jackson Harrison, Charles M. Haskell, rifice would later be remembered along the John M. Hays, William Marshall, Jesse Americans: ask not what your country can do banks of the San Jacinto as GEN Sam Hous- McCoy, Robert McKinney, Thomas R. Miller, for you—ask what you can do for your coun- ton led the Texans to victory and freedom. But William Mills, Andrew M. Nelson, James Wa- try.’’ their courage will never be forgotten. ters Robertson, Andrew H. Smith, A. Spain This message still rings out strong and true Travis isn’t just my favorite Texas war hero, Summerlin, William E. Summers, Edward in this new century. Love of country still has he has intertwined himself throughout my life Taylor, George Taylor, James Taylor, Wil- a powerful and appropriate role in motivating and even the lives of my children and grand- liam Taylor, Asa Walker, Jacob Walker. our young people to take up service, and the children. He is the inspiration behind my pro- Texas: Juan Abamillo, Juan Antonio people of this Nation take proper pride in the Badillo, Carlos Espalier, Gregorio (Jose fession. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions Of

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E269 to discourage unauthorized workers from en- I am besieged by a thousand or more of the Illinois: Jonathan L. Lindley. tering this country illegally to seek work. En- enemy under Santa Anna. I have sustained a Kentucky: Peter James Bailey III, James suring a legal workforce must be a key com- continual bombardment and cannon fire for Bowie, Daniel William Cloud, Jacob C. Darst, over 24 hours, but I have not lost a man. John Davis, William H. Fauntleroy, John E. ponent of any immigration bill moving through The enemy has demanded surrender at its Gaston, John Harris, William Daniel Jack- Congress. discretion. Otherwise, the fort will be put to son, Green B. Jameson, John Benjamin Kel- I look forward to working with my colleagues the sword. I have answered that demand with logg, Andrew Kent, Joseph Rutherford, B. to build on this proposal to achieve a bipar- a cannon shot. And the flag still waves Archer M. Thomas, Joseph G. Washington. tisan solution to immigration reform. proudly over the north wall. Louisiana: Charles Despallier, James W. I shall never surrender or retreat. I call Garrand, Joseph Kerr, Isaac Ryan. f upon you, in the name of liberty and patriot- Maryland: Charles S. Smith. HONORING BROOKE EDWARDS ism and everything dear to the American Massachusetts: John Flanders, William D. character, to come to my aid with all dis- Howell, William Linn, Amos Pollard. patch. If this call is neglected, I am deter- Mississippi: M.B. Clark, Isaac Millsaps, HON. LYNN A. WESTMORELAND mined to sustain myself for as long as pos- Willis A. -

Papers, 1812-1949

Texas A&M University-San Antonio Digital Commons @ Texas A&M University-San Antonio Finding Aids: Guides to the Collection Archives & Special Collections 2020 Asbury (Samuel E.) Papers, 1812-1949 DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tamusa.edu/findingaids A Guide to the Samuel E. Asbury Papers, 1812-1949 Descriptive Summary Creator: Asbury, Samuel E. (Samuel Erson), 1872-1962 Title: Samuel E. Asbury Papers Dates: 1812-1949 Creator Professionally employed as a chemist with the Texas Agricultural Abstract: Experiment Station on the Texas A&M campus, Samuel E. Asbury (1872-1962) was also interested in Texas history. He conducted extensive research about the state's past, particularly the Texas Revolution, corresponding widely and collecting historically important documents. Content Correspondence, legal documents, newspaper clippings, and other Abstract: published material related to Texas history make up the Samuel E. Asbury Papers. The bulk of the papers consist of typescript copies of correspondence and source documents produced and received by Asbury in the course of his historical research. Much of the research is related to the Texas Revolution and the Republic of Texas; particularly in-depth is material on the Goliad Massacre, Jonas Harrison, the Regulator-Moderator War, and John A. Williams. Identification: Col 872 Extent: 2.71 linear feet (7 boxes) Language: Materials are in English. Repository: DRT Collection at Texas A&M University-San Antonio Biographical Note Samuel Erson Asbury was born on 1872 September 26 in Charlotte, North Carolina. He received his college education at North Carolina State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts in Raleigh (now North Carolina State University), earning Bachelor's and Master's degrees in chemistry.