Vol 04 Issue 2

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

Adventure Interpreter by Scott Adams .• , ..•••.••..••..•.•....••.•....•

..... ........ ~ "I'd lie AVALON One Player Simulation Games * B-1 Bomber * Nukewar * North Atlantic Convoy Raider * Midway Campaign For one to four players * Planet Miners At last! Quality computer simulation games from the leader in war gamingl All games available for 16K Level II TRS-80, 16K Applesoft in ROM or Apple II Plus, and 16K Pet 2001 computers. $14.95 eachl JlteSoltttare Exchange 6 SOUTH ·ST., MILFORD. N.H. 03065 (803) 673.. 514-4 2 YOUR BASIC SOFTWARE MAGAZINE VOL.2, NO.10 IN THIS ISSUE ... Adventures by James Garon .....•.••.....•..•... , •.•. " ..•..• 17 Mlcro-lO Pinball Machine by Garth Jensen .•••.•.......•....••..•.••••..••.• 22 Take Apart Pinball by Garth Jensen .....••..••..•••..•......•....•.•• 30 AdYentureiand by Scott Adams ....••...•••.•.••.•.....••.••..•.• 36 Adventure Interpreter by Scott Adams .• , ..•••.••..••..•.•....••.•....•. 44 LOlt Dutchman', Gold by Teri Li .......••....•••.....•........•.•....... 58 REGULAR FEATURES ... Outgoing Mall. .. 6 Programming Hints ............................... 14 Input ••.•.•.....•...•..•..••...•.....•...••..•... 50 Bug Report ..............•..•....•.....••..•...•. 70 Market aalket .•.•....••...•.....•...•.••••..••... 74 Convenient Order Forms .......................... 78 cover illustration of Adventureland by Elaine Cheever 3 __(,-",soft5i"ao~ .. ...1-] -- STAFF SoftSide Publications The Software Exchange PuIIII"'... CllIID_ Sll'fh:l I'IIIIIQIoI .. CMnlflllllr RoQer W. RobOtalile. $r, Bette )(eet\lln 8iza!Jeth RobUali1e Elllllr4l.QIII OIf1C11r or fbrt ....U Georgi Blank -

Dragon Magazine

DRAGON 1 Publisher: Mike Cook Editor-in-Chief: Kim Mohan Shorter and stronger Editorial staff: Marilyn Favaro Roger Raupp If this isnt one of the first places you Patrick L. Price turn to when a new issue comes out, you Mary Kirchoff may have already noticed that TSR, Inc. Roger Moore Vol. VIII, No. 2 August 1983 Business manager: Mary Parkinson has a new name shorter and more Office staff: Sharon Walton accurate, since TSR is more than a SPECIAL ATTRACTION Mary Cossman hobby-gaming company. The name Layout designer: Kristine L. Bartyzel change is the most immediately visible The DRAGON® magazine index . 45 Contributing editor: Ed Greenwood effect of several changes the company has Covering more than seven years National advertising representative: undergone lately. in the space of six pages Robert Dewey To the limit of this space, heres some 1409 Pebblecreek Glenview IL 60025 information about the changes, mostly Phone (312)998-6237 expressed in terms of how I think they OTHER FEATURES will affect the audience we reach. For a This issues contributing artists: specific answer to that, see the notice Clyde Caldwell Phil Foglio across the bottom of page 4: Ares maga- The ecology of the beholder . 6 Roger Raupp Mary Hanson- Jeff Easley Roberts zine and DRAGON® magazine are going The Nine Hells, Part II . 22 Dave Trampier Edward B. Wagner to stay out of each others turf from now From Malbolge through Nessus Larry Elmore on, giving the readers of each magazine more of what they read it for. Saved by the cavalry! . 56 DRAGON Magazine (ISSN 0279-6848) is pub- I mention that change here as an lished monthly for a subscription price of $24 per example of what has happened, some- Army in BOOT HILL® game terms year by Dragon Publishing, a division of TSR, Inc. -

Donald Featherstone's Air War Games: Wargaming Aerial Warfare 1914

Donald Featherstone’s Air War Games Wargaming Aerial Warfare 1914-1975 Revised Edition Edited by John Curry This book was first published in 1966 as Air War Games by Stanley and Paul. This edition 2015 Copyright © 2015 John Curry and Donald Featherstone Sturmstaffel: Defending the Reich is copyright of Tim Gow; Rolling Thunder is copyright Ian Drury, and On a Wing and Prayer is copyright John Armatys. All three sets of rules are reproduced with permission. With thanks to all three of these people who kindly contributed to this new edition. The right of John Curry and Donald Featherstone to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior written permission of the authors in writing. More than 30 books are currently in the History of Wargaming Project Army Wargames: Staff College Exercises 1870-1980. Charlie Wesencraft’s Practical Wargaming Charlie Wesencraft’s With Pike and Musket Donald Featherstone’s Lost Tales Donald Featherstone’s War Games Donald Featherstone’s Skirmish Wargaming Donald Featherstone’s Naval Wargames Donald Featherstone’s Advanced Wargames Donald Featherstone’s Wargaming Campaigns Donald Featherstone’s Solo Wargaming Paddy Griffith’s Napoleonic Wargaming for Fun Sprawling Wargames: Multi-player wargaming by Paddy Griffith Verdy’s ‘Free Kriegspiel’ including the Victorian Army’s 1896 War Game Tony Bath’s Ancient Wargaming Phil Dunn’s Sea Battles Joseph Morschauser’s How to Play War Games in Miniature And many others See The History of Wargaming Project for other publications. -

Avalon Hill Microcomputer Games Catalog Spring 1984

NEW for SPRING of '84! *ifT Jr — jifcr V ~ > • Strategy, Science Fiction, Fantasy, Adventure, Educational, •* '» a . mvts»ON c* Sports & Arcade GAMES for the HOME COMPUTER mrvti QUALITY microcomputer games A Division of The AVALON HILL Game Company New Strategy War Games: DREADNOUGHTS Recreate ALL of the major naval action in the North Atlantic during the early years (1939-41) of the Second World War. Most ALL of the major warships actually utilized by the British, German, French and American navies are represented. Playing the game on both strategic and tac- tical levels one or two players create very realistic battle engagements where the most minute details are at their disposal. Nearly EVERYTHING is taken into account; gun sizes, range, ship armor, ship speed, radar, torpedoes, air- craft and much, much more. lie. #45552 Available on diskette (48K) for Apple II, II + , and 1 or 2 players, Playing Time: IV2 hours (7) $30.00 GULF STRIKE Perhaps the world's most critical flashpoint, the Persian Gulf is an area fraught with ideological, economic, political, and military animosities where every flare-up car- ries the threat of global repercussions. GULF STRIKE allows one or two players to examine most every aspect of this complex region where the potential for superpower con- frontation is imminent. This is a brigade level simulation pit- ting Iran and ihe U.S.A. vs. Iraq and the U.S.3.R. complete with fine scrolling map and a unique way of handling unit stacks. #44953 Available on diskette (48K) for Atari Home Com- puters, joystick required. -

Computer Gaming Cover As Well

$ 2.50 NOVEMBER 1981 NUMBER 45 THE MAGAZINE OF ADVENTURE GAMING Special Computer Issue PLAY-BY-PHONE ARRIVES WINNING STRATEGY FOR STA RWEB AUTOMATED SIMULATIONS COMPANY REPORT DESIGNER'S NOTES FOR CAR WARS GRIMTOOTH'S TRAP NEBULA 19 11 PAGES OF REVIEW' 1 IN THIS ISSUE It seemed like time for another com- puter issue . and here it is. Don't you NUMBER 45 — NOVEMBER, 1981 non-computerized types give up, though. On page 12, we have an article about the newest wrinkle in gaming: play-by- Articles phone. Unlike PBM gaming, it doesn't (yet) allow you the benefits of com- STAR WEB * W.G. Armintrout puter gaming without the expense. Six ways to stop your losing streak 8 But its potential is big enough to make KILLER computer owners out of a lot of people Using the Earth's rotation to wipe out your friends 15 who've held back so far. DESIGNER'S NOTES: GRIMTOOTH'S TRAPS * Paul O'Connor Also on the computer front: a Starweb The evolution of FBI's book of nasty surprises 16 strategy article, a review of Robot War, and the Automated Simula- NOTES FOR REVIEWERS * Lewis Pulsipher tions company report. Several tips on writing to-the-point reviews 21 We've also got an article each on our GLOSSARY CONTEST RESULTS own new hits. For you Killer fans, the More definitions of very familiar gaming terms 22 long-awaited answer to the rotation-of- DESIGNER'S NOTES: CAR WARS * Chad Irby the-earth problem. And Chad Irby, co- The making of Car Wars, and some useful hints 25 designer of Car Wars, tells how it all got started. -

The AVALON HILL

N... "'0'".. ... '" 2 *The AVALON HILL ic': ~iiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiAiiiiiiiViiiiiiiaiiiiiiilOiiiiiiiniiiiiiiHiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiliiiiiiilPiiiiiiihiiiiiiiiiiiiiiilOiiiiiiiSiiiiiiiPiiiiiiihYiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiPiiiiiiiariiiiiiitiiiiiii9iiiiiiioiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiiii~ GENERAL Has it really been ten years? As I ponder bring grognard on any readership. You've suffered long The Game Players Magazine ing this column to life for the 60th time it seems enough at my hands. The opportunity for your hard to believe, but calendars don't lie. Vol. 9, No. magazine to take on fresh ideas under new leader The Avalon Hill GENERAL is dediCated to the presenta" 1 was my maiden voyage as editor of THE ship is long overdue. While I am genuinely proud of lion of authoritative articles on the strategy; tactics, and GENERAL, and now a scant ten years later I must the format we have developed for THE GENERAL variation of Avalon Hill wargames. Historical articles are Jncludedonly insomuch as they provide useful background relinquish the helm to another as time marches on. during the past decade, perhaps greater things can information On current Avalon Hill titles. The GENERALis For this, dear reader, is my last issue as your trusty be accomplished from the vantage point of a fresh published by the Avalon Hill Game CompanY solelv fot the (or is that crusty) old editor. perspective. I have been advised from time to time aficionado,rn~the cultural edification of the serious game that mine is a rather opinionated and dry style much hopes ofimpfoving the game owner's proficiency of play and providing services not otherwise available to the Avalon Hill too grating on the nerves of those with dissimilar game buff .. Avalon Hill is a division of Monarch Avalon Yes, I've finally been kicked upstairs into the tastes. -

Website Listing Ajax

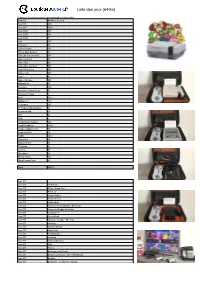

Liste des jeux (64Go) Cliquez sur le nom des consoles pour descendre au bon endroit Console Nombre de jeux Atari ST 274 Atari 800 5627 Atari 2600 457 Atari 5200 101 Atari 7800 51 C64 150 Channel F 34 Coleco Vision 151 Family Disk System 43 FBA Libretro (arcade) 647 Game & watch 58 Game Boy 621 Game Boy Advance 951 Game Boy Color 501 Game gear 277 Lynx 84 Mame (arcade) 808 Nintento 64 78 Neo-Geo 152 Neo-Geo Pocket Color 81 Neo-Geo Pocket 9 NES 1812 Odyssey 2 125 Pc Engine 291 Pc Engine Supergraphx 97 Pokémon Mini 26 PS1 54 PSP 2 Sega Master System 288 Sega Megadrive 1030 Sega megadrive 32x 30 Sega sg-1000 59 SNES 1461 Stellaview 66 Sufami Turbo 15 Thomson 82 Vectrex 75 Virtualboy 24 Wonderswan 102 WonderswanColor 83 Total 16877 Atari ST Atari ST 10th Frame Atari ST 500cc Grand Prix Atari ST 5th Gear Atari ST Action Fighter Atari ST Action Service Atari ST Addictaball Atari ST Advanced Fruit Machine Simulator Atari ST Advanced Rugby Simulator Atari ST Afterburner Atari ST Alien World Atari ST Alternate Reality - The City Atari ST Anarchy Atari ST Another World Atari ST Apprentice Atari ST Archipelagos Atari ST Arcticfox Atari ST Artificial Dreams Atari ST Atax Atari ST Atomix Atari ST Backgammon Royale Atari ST Balance of Power - The 1990 Edition Atari ST Ballistix Atari ST Barbarian : Le Guerrier Absolu Atari ST Battle Chess Atari ST Battle Probe Atari ST Battlehawks 1942 Atari ST Beach Volley Atari ST Beastlord Atari ST Beyond the Ice Palace Atari ST Black Tiger Atari ST Blasteroids Atari ST Blazing Thunder Atari ST Blood Money Atari ST BMX Simulator Atari ST Bob Winner Atari ST Bomb Jack Atari ST Bumpy Atari ST Burger Man Atari ST Captain Fizz Meets the Blaster-Trons Atari ST Carrier Command Atari ST Cartoon Capers Atari ST Catch 23 Atari ST Championship Baseball Atari ST Championship Cricket Atari ST Championship Wrestling Atari ST Chase H.Q. -

Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, Ca

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/kt529018f2 No online items Guide to the Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, ca. 1975-1995 Processed by Stephan Potchatek; machine-readable finding aid created by Steven Mandeville-Gamble Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc © 2001 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Special Collections M0997 1 Guide to the Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, ca. 1975-1995 Collection number: M0997 Department of Special Collections and University Archives Stanford University Libraries Stanford, California Contact Information Department of Special Collections Green Library Stanford University Libraries Stanford, CA 94305-6004 Phone: (650) 725-1022 Email: [email protected] URL: http://library.stanford.edu/spc Processed by: Stephan Potchatek Date Completed: 2000 Encoded by: Steven Mandeville-Gamble © 2001 The Board of Trustees of Stanford University. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Stephen M. Cabrinety Collection in the History of Microcomputing, Date (inclusive): ca. 1975-1995 Collection number: Special Collections M0997 Creator: Cabrinety, Stephen M. Extent: 815.5 linear ft. Repository: Stanford University. Libraries. Dept. of Special Collections and University Archives. Language: English. Access Access restricted; this collection is stored off-site in commercial storage from which material is not routinely paged. Access to the collection will remain restricted until such time as the collection can be moved to Stanford-owned facilities. Any exemption from this rule requires the written permission of the Head of Special Collections. -

American Strategy in the Pacific After Midway: from Parity to Supremacy

American Strategy in the Pacific after Midway: From Parity to Supremacy Phillips O’Brien Historians revel in discussing what they consider to be the decisive turning points of great wars. For the Second World War in the Pacific the identified turning point for western, particularly European historians is the Battle of Midway in June 1942. After this encounter, so most have reasoned, the course of the Pacific War was determined. Japan was to be crushed, overwhelmed by the sheer bulk of American material. While the time line might have some ambiguity, the end result could not. Even American disasters such as the battle of Savo Island just weeks later, followed by the destruction of two large aircraft carriers in the following months, were mere details on the road to eventual American victory. The period of this paper, sandwiched between Midway and the other ‘decisive’ engagement of the Pacific war—the Battle of the Philippine Sea (June 1944), is therefore sometimes seen as one of planning and organization, if relatively little decisive action.. In terms of the area fought over, there is something to this. Until the landings in the Gilberts in late 1943, most fighting in the Pacific occurred in a relatively small area stretching from Guadalcanal to Rabaul. Considering the vast size of the Pacific theatre of operations, the fighting occurred on the very fringes. Yet, on reflection, it makes little sense to see this period as a whole, because, for the US Navy at least, it was divided into two noticeably distinct campaigning eras; one of parity and the other of a growing supremacy. -

Priceless Advantage 2017-March3.Indd

United States Cryptologic History A Priceless Advantage U.S. Navy Communications Intelligence and the Battles of Coral Sea, Midway, and the Aleutians series IV: World War II | Volume 5 | 2017 Center for Cryptologic History Frederick D. Parker retired from NSA in 1984 after thirty-two years of service. Following his retirement, he worked as a reemployed annuitant and volunteer in the Center for Cryptologic History. Mr. Parker served in the U.S. Marine Corps from 1943 to 1945 and from 1950 to 1952. He holds a B.S. from the Georgetown University School of Foreign Service. This publication presents a historical perspective for informational and educational purposes, is the result of independent research, and does not necessarily reflect a position of NSA/CSS or any other U.S. govern- ment entity. This publication is distributed free by the National Security Agency. If you would like additional copies, please email [email protected] or write to: Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency 9800 Savage Road, Suite 6886 Fort George G. Meade, MD 20755 Cover: (l to r) Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander in Chief, Japanese Combined Fleet, 1942; aircraft preparing for launch on the USS Enterprise during the Battle of Midway on 4 June 1942 with the USS Pensacola and a destroyer in distance; and Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, ca. 1942-1944 A Priceless Advantage: U.S. Navy Communications Intelligence and the Battles of Coral Sea, Midway, and the Aleutians Frederick D. Parker Center for Cryptologic History National Security Agency Reissued 2017 with a new introduction First edition published 1993.