Priceless Advantage 2017-March3.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

THE BATTLE of the CORAL SEA — an OVERVIEW by A.H

50 THE BATTLE OF THE CORAL SEA — AN OVERVIEW by A.H. Craig Captain Andrew H. Craig, RANEM, served in the RAN 1959 to 1988, was Commanding officer of 817 Squadron (Sea King helicopters), and served in Vietnam 1968-1979, with the RAN Helicopter Flight, Vietnam and No.9 Squadroom RAAF. From December 1941 to May 1942 Japanese armed forces had achieved a remarkable string of victories. Hong Kong, Malaya and Singapore were lost and US forces in the Philippines were in full retreat. Additionally, the Japanese had landed in Timor and bombed Darwin. The rapid successes had caught their strategic planners somewhat by surprise. The naval and army staffs eventually agreed on a compromise plan for future operations which would involve the invasion of New Guinea and the capture of Port Moresby and Tulagi. Known as Operation MO, the plan aimed to cut off the eastern sea approaches to Darwin and cut the lines of communication between Australia and the United States. Operation MO was highly complex and involved six separate naval forces. It aimed to seize the islands of Tulagi in the Solomons and Deboyne off the east coast of New Guinea. Both islands would then be used as bases for flying boats which would conduct patrols into the Coral Sea to protect the flank of the Moresby invasion force which would sail from Rabaul. That the Allied Forces were in the Coral Sea area in such strength in late April 1942 was no accident. Much crucial intelligence had been gained by the American ability to break the Japanese naval codes. -

Georgetown University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Security Studies

THE BATTLE FOR INTELLIGENCE: HOW A NEW UNDERSTANDING OF INTELLIGENCE ILLUMINATES VICTORY AND DEFEAT IN WORLD WAR II A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Security Studies By Edward J. Piotrowicz III, B.A. Washington, DC April 15, 2011 Copyright 2011 by Edward J. Piotrowicz III All Rights Reserved ii THE BATTLE FOR INTELLIGENCE: HOW A NEW UNDERSTANDING OF INTELLIGENCE ILLUMINATES VICTORY AND DEFEAT IN WORLD WAR II Edward J. Piotrowicz III, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Jennifer E. Sims, PhD. ABSTRACT Does intelligence make a difference in war? Two World War II battles provide testing grounds for answering this question. Allied intelligence predicted enemy attacks at both Midway and Crete with uncanny accuracy, but the first battle ended in an Allied victory, while the second finished with crushing defeat. A new theory of intelligence called “Decision Advantage,”a illuminates how the success of intelligence helped facilitate victory at Midway and how its dysfunction contributed to the defeat at Crete. This view stands in contrast to that of some military and intelligence scholars who argue that intelligence has little impact on battle. This paper uses the battles of Midway and Crete to test the power of Sims‟s theory of intelligence. By the theory‟s standards, intelligence in the case of victory outperformed intelligence in the case of defeat, suggesting these cases uphold the explanatory power of the theory. Further research, however, could enhance the theory‟s prescriptive power. -

Book Reviews

BOOK REVIEWS David Childs. Invading America: The cleverly written synthesis. Childs has an English Assault on the New World, 1497- excellent grasp of the material, and an 1630. Barnsley, S. Yorks.: Pen & Sword impressive command of the primary Books Limited, www.pen-and-sword.co.uk, sources. While his focus may be too broad 2012. xi + 306 pp., illustrations, maps, for specialist readers, Childs should be appendices, notes, bibliography, index. UK commended for attempting to blaze a new £25.00, cloth; ISBN 978-1-84832-145-8. trail into this well-trodden territory. Childs’ declared timeframe is the Historians since Hakluyt have remarked on “long sixteenth century,” from John Cabot England’s slowness in establishing New to John Winthrop. The information on World colonies, especially in comparison Cabot is sketchy in the extreme, however, with her rival, Spain. David Childs seeks to and the author focuses almost exclusively explain the widespread failure of early on the period between Frobisher’s first English colonies by viewing them as voyage in 1576 and the Jamestown beachheads in an extended amphibious massacre of 1622. A literature review campaign. Childs identifies the factors identifies the intellectual underpinnings for crucial for successful amphibious New World voyages, ranging from John operations, which, when absent, doomed Donne to the King James Bible. The failure would-be settlers from Baffin Island to the of the Roanoke colony on the windswept Carolinas. These factors included proper reconnaissance and intelligence, sufficient Carolina Outer Banks is used to illustrate forces and supplies, realistic objectives, the importance of proper reconnaissance effective naval forces and joint command, and site selection. -

Air Raid Colombo, 5 April 1942: the Fully Expected Surprise Attack

THE ROYAL CANADIAN AIR FORCE JOURNAL VOL. 3 | NO. 4 FALL 2014 Air Raid Colombo, 5 April 1942: The Fully Expected Surprise Attack B Y RO B E R T S TUA R T Introduction n the morning of 5 April 1942, a force of 127 aircraft from the five aircraft carriers of Kido Butai (KdB), the Imperial Japanese Navy’s carrier task force, attacked Colombo, O the capital and principal port of the British colony of Ceylon (now Sri Lanka). This was no bolt from the blue, however. The defenders had been preparing for weeks for just such an eventuality. Reconnaissance aircraft had detected KdB’s approach the previous afternoon and tracked it during the night. The defending aircraft and anti-aircraft (AA) guns had come to full readiness before first light and were supported by an operational radar station. The defending fighters were nevertheless still on the ground when the Japanese aircraft arrived and were not scrambled until the pilots themselves saw the attackers overhead. As a result, the defenders lost 20 of the 41 fighters that took off, while the Japanese lost only seven aircraft. So what happened? Was there a problem with the radar, did someone blunder, or was there some other explanation? This article is a first look into why the defenders were caught on the ground. Reinforcements On 7 December 1941, the air defences of Ceylon consisted of four obsolescent three-inch AA guns at Trincomalee. The only Royal Air Force (RAF) unit was 273 Squadron at China Bay, near Trincomalee, with four Vildebeests and four Seals, both of which were obsolete biplane torpedo aircraft. -

From the Nisshin to the Musashi the Military Career of Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku by Tal Tovy

Asia: Biographies and Personal Stories, Part II From the Nisshin to the Musashi The Military Career of Admiral Yamamoto Isoroku By Tal Tovy Detail from Shugaku Homma’s painting of Yamamoto, 1943. Source: Wikipedia at http://tinyurl.com/nowc5hg. n the morning of December 7, 1941, Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) aircraft set out on one of the most famous operations in military Ohistory: a surprise air attack on the US naval base at Pearl Harbor, Hawai`i. The attack was devised and fashioned by Admiral Yamamoto, whose entire military career seems to have been leading to this very moment. Yamamoto was a naval officer who appreciated and under- stood the strategic and technological advantages of naval aviation. This essay will explore Yamamoto’s military career in the context of Imperial Japan’s aggressive expansion into Asia beginning in the 1890s and abruptly ending with Japan’s formal surrender on September 2, 1945, to the US and its Allies. Portrait of Yamamoto just prior to the Russo- Japanese War, 1905. Early Career (1904–1922) Source: World War II Database Yamamoto Isoroku was born in 1884 to a samurai family. Early in life, the boy, thanks to at http://tinyurl.com/q2au6z5. missionaries, was exposed to American and Western culture. In 1901, he passed the Impe- rial Naval Academy entrance exams with the objective of becoming a naval officer. Yamamoto genuinely respected the West—an attitude not shared by his academy peers. The IJN was significantly influenced by the British Royal Navy (RN), but for utilitarian reasons: mastery of technology, strategy, and tactics. -

![[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3367/japan-sala-giochi-arcade-1000-miglia-393367.webp)

[Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia

SCHEDA NEW PLATINUM PI4 EDITION La seguente lista elenca la maggior parte dei titoli emulati dalla scheda NEW PLATINUM Pi4 (20.000). - I giochi per computer (Amiga, Commodore, Pc, etc) richiedono una tastiera per computer e talvolta un mouse USB da collegare alla console (in quanto tali sistemi funzionavano con mouse e tastiera). - I giochi che richiedono spinner (es. Arkanoid), volanti (giochi di corse), pistole (es. Duck Hunt) potrebbero non essere controllabili con joystick, ma richiedono periferiche ad hoc, al momento non configurabili. - I giochi che richiedono controller analogici (Playstation, Nintendo 64, etc etc) potrebbero non essere controllabili con plance a levetta singola, ma richiedono, appunto, un joypad con analogici (venduto separatamente). - Questo elenco è relativo alla scheda NEW PLATINUM EDITION basata su Raspberry Pi4. - Gli emulatori di sistemi 3D (Playstation, Nintendo64, Dreamcast) e PC (Amiga, Commodore) sono presenti SOLO nella NEW PLATINUM Pi4 e non sulle versioni Pi3 Plus e Gold. - Gli emulatori Atomiswave, Sega Naomi (Virtua Tennis, Virtua Striker, etc.) sono presenti SOLO nelle schede Pi4. - La versione PLUS Pi3B+ emula solo 550 titoli ARCADE, generati casualmente al momento dell'acquisto e non modificabile. Ultimo aggiornamento 2 Settembre 2020 NOME GIOCO EMULATORE 005 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1 On 1 Government [Japan] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1000 Miglia: Great 1000 Miles Rally SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 10-Yard Fight SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 18 Holes Pro Golf SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1941: Counter Attack SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1942 SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1943: The Battle of Midway [Europe] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1944 : The Loop Master [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 1945k III SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 19XX : The War Against Destiny [USA] SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 2 On 2 Open Ice Challenge SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 4-D Warriors SALA GIOCHI ARCADE 64th. -

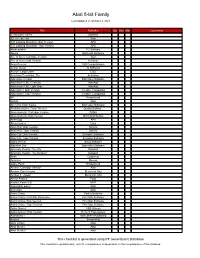

Atari 8-Bit Family

Atari 8-bit Family Last Updated on October 2, 2021 Title Publisher Qty Box Man Comments 221B Baker Street Datasoft 3D Tic-Tac-Toe Atari 747 Landing Simulator: Disk Version APX 747 Landing Simulator: Tape Version APX Abracadabra TG Software Abuse Softsmith Software Ace of Aces: Cartridge Version Atari Ace of Aces: Disk Version Accolade Acey-Deucey L&S Computerware Action Quest JV Software Action!: Large Label OSS Activision Decathlon, The Activision Adventure Creator Spinnaker Software Adventure II XE: Charcoal AtariAge Adventure II XE: Light Gray AtariAge Adventure!: Disk Version Creative Computing Adventure!: Tape Version Creative Computing AE Broderbund Airball Atari Alf in the Color Caves Spinnaker Software Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves Quality Software Alien Ambush: Cartridge Version DANA Alien Ambush: Disk Version Micro Distributors Alien Egg APX Alien Garden Epyx Alien Hell: Disk Version Syncro Alien Hell: Tape Version Syncro Alley Cat: Disk Version Synapse Software Alley Cat: Tape Version Synapse Software Alpha Shield Sirius Software Alphabet Zoo Spinnaker Software Alternate Reality: The City Datasoft Alternate Reality: The Dungeon Datasoft Ankh Datamost Anteater Romox Apple Panic Broderbund Archon: Cartridge Version Atari Archon: Disk Version Electronic Arts Archon II - Adept Electronic Arts Armor Assault Epyx Assault Force 3-D MPP Assembler Editor Atari Asteroids Atari Astro Chase Parker Brothers Astro Chase: First Star Rerelease First Star Software Astro Chase: Disk Version First Star Software Astro Chase: Tape Version First Star Software Astro-Grover CBS Games Astro-Grover: Disk Version Hi-Tech Expressions Astronomy I Main Street Publishing Asylum ScreenPlay Atari LOGO Atari Atari Music I Atari Atari Music II Atari This checklist is generated using RF Generation's Database This checklist is updated daily, and it's completeness is dependent on the completeness of the database. -

The Lower Bathyal and Abyssal Seafloor Fauna of Eastern Australia T

O’Hara et al. Marine Biodiversity Records (2020) 13:11 https://doi.org/10.1186/s41200-020-00194-1 RESEARCH Open Access The lower bathyal and abyssal seafloor fauna of eastern Australia T. D. O’Hara1* , A. Williams2, S. T. Ahyong3, P. Alderslade2, T. Alvestad4, D. Bray1, I. Burghardt3, N. Budaeva4, F. Criscione3, A. L. Crowther5, M. Ekins6, M. Eléaume7, C. A. Farrelly1, J. K. Finn1, M. N. Georgieva8, A. Graham9, M. Gomon1, K. Gowlett-Holmes2, L. M. Gunton3, A. Hallan3, A. M. Hosie10, P. Hutchings3,11, H. Kise12, F. Köhler3, J. A. Konsgrud4, E. Kupriyanova3,11,C.C.Lu1, M. Mackenzie1, C. Mah13, H. MacIntosh1, K. L. Merrin1, A. Miskelly3, M. L. Mitchell1, K. Moore14, A. Murray3,P.M.O’Loughlin1, H. Paxton3,11, J. J. Pogonoski9, D. Staples1, J. E. Watson1, R. S. Wilson1, J. Zhang3,15 and N. J. Bax2,16 Abstract Background: Our knowledge of the benthic fauna at lower bathyal to abyssal (LBA, > 2000 m) depths off Eastern Australia was very limited with only a few samples having been collected from these habitats over the last 150 years. In May–June 2017, the IN2017_V03 expedition of the RV Investigator sampled LBA benthic communities along the lower slope and abyss of Australia’s eastern margin from off mid-Tasmania (42°S) to the Coral Sea (23°S), with particular emphasis on describing and analysing patterns of biodiversity that occur within a newly declared network of offshore marine parks. Methods: The study design was to deploy a 4 m (metal) beam trawl and Brenke sled to collect samples on soft sediment substrata at the target seafloor depths of 2500 and 4000 m at every 1.5 degrees of latitude along the western boundary of the Tasman Sea from 42° to 23°S, traversing seven Australian Marine Parks. -

Japan's Pacific Campaign

2 Japan’s Pacific Campaign MAIN IDEA WHY IT MATTERS NOW TERMS & NAMES EMPIRE BUILDING Japan World War II established the • Isoroku •Douglas attacked Pearl Harbor in Hawaii United States as a leading player Yamamoto MacArthur and brought the United States in international affairs. •Pearl Harbor • Battle of into World War II. • Battle of Guadalcanal Midway SETTING THE STAGE Like Hitler, Japan’s military leaders also had dreams of empire. Japan’s expansion had begun in 1931. That year, Japanese troops took over Manchuria in northeastern China. Six years later, Japanese armies swept into the heartland of China. They expected quick victory. Chinese resistance, however, caused the war to drag on. This placed a strain on Japan’s economy. To increase their resources, Japanese leaders looked toward the rich European colonies of Southeast Asia. Surprise Attack on Pearl Harbor TAKING NOTES Recognizing Effects By October 1940, Americans had cracked one of the codes that the Japanese Use a chart to identify used in sending secret messages. Therefore, they were well aware of Japanese the effects of four major plans for Southeast Asia. If Japan conquered European colonies there, it could events of the war in the also threaten the American-controlled Philippine Islands and Guam. To stop the Pacific between 1941 and 1943. Japanese advance, the U.S. government sent aid to strengthen Chinese resistance. And when the Japanese overran French Indochina—Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos—in July 1941, Roosevelt cut off oil shipments to Japan. Event Effect Despite an oil shortage, the Japanese continued their conquests. They hoped to catch the European colonial powers and the United States by surprise. -

The Battle of Midway

OVERVIEW ESSAY: The Battle of Midway (Naval History and Heritage Command, NH 73065.) One of Japan’s main goals during World War II was to THE BATTLE remove the United States as a Pacific power in order Early on the morning of June 4, aircraft from four to gain territory in east Asia and the southwest Pacific Japanese aircraft carriers attacked and severely islands. Japan hoped to defeat the US Pacific Fleet and damaged the US base on Midway. Unbeknownst to the use Midway as a base to attack Pearl Harbor, securing Japanese, the US carrier forces were just to the east of dominance in the region and then forcing a negotiated the island and ready for battle. After their initial attacks, peace. the Japanese aircraft headed back to their carriers to BREAKING THE CODE rearm and refuel. While the aircraft were returning, the Japanese navy became aware of the presence of US The United States was aware that the Japanese naval forces in the area. were planning an attack in the Pacific (on a TBD Devastator torpedo-bombers and SBD Dauntless location the Japanese code-named “AF”) because dive-bombers from the USS Enterprise, USS Hornet, Navy cryptanalysts had begun breaking Japanese and USS Yorktown attacked the Japanese fleet. The communication codes in early 1942. The attack location Japanese carriers Akagi, Kaga, and Soryu were hit, and time were confirmed when the American base at set ablaze, and abandoned. Hiryu, the only surviving Midway sent out a false message that it was short of Japanese carrier, responded with two waves of fresh water. -

Rochefort Vinse a Midway, Fu Sconfitto a Washington

StO ROCHEFORT VINSE A MIDWAY, FU SCONFITTO A WASHINGTON ALAIN CHARBONNIER «Si può raggiungere qualsiasi risultato, purché nessuno badi a chi va il merito», era scritto alle spalle del capitano di vascello Joseph J. Rochefort nel Dungeon, il seminterrato di Pearl Harbour, dove i decrittatori della stazione ‘Hypo’ che lavoravano sui codici della Marina giapponese misero l’ammiraglio Nimitz in grado di vincere a Midway. Ma c’era chi al merito badava, e come, e voleva appropriarsene. Rochefort era approdato alla crittoanalisi quando negli Stati Uniti era considerata quasi una stregoneria. Sedici anni dopo, nonostante i brillanti risultati, ne fu estromesso dai burocrati di Washington. «Un ex studente di giapponese non può comandare un centro dell’intelligence navale», dissero. La vittoria di Midway fu ascritta a suo merito soltanto nel 1985, nove anni dopo la morte. Impianto desalinizzazione in avaria. Riserva acqua potabile prevista in 14 giorni con razionamento. Provvedere rifornimento». Il 20 maggio 1942 il Comando della Marina americana a Pearl Harbour, nelle isole Hawaii, ricevette il messaggio ‘flash’ tramesso dalla guarnigione di Midway, un atollo distante quasi 2000 chilometri, da poco tempo rinforzata dal Comando del Pacifico. I centri d’ascolto giapponesi intercettarono la comunicazione e avvertirono il Co - mando Generale della Nihon Kaigun , la flotta imperiale, che ‘l’unità aerea AF’ aveva chiesto un immediato rifornimento idrico. Il messaggio giapponese, criptato nel codice JN-25, fu captato e decodificato anche dalla stazione ‘Hypo’, di Honolulu, alle Hawaii, dove il capitano di vascello Joseph J. Rochefort lo stava aspettando. Per lui era la conferma che la sigla ‘AF’ indicava Midway, come aveva intuito nelle settimane precedenti, quando si era delineata l’ipotesi che i Giapponesi stessero preparando una nuova offensiva. -

Tokyo Bay the AAF in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater

The U.S. Army Air Forces in World War II The High Road to Tokyo Bay The AAF in the Asiatic-Pacific Theater Daniel Haulman Air Force Historical Research Agency DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A Approved for Public Release Distribution Unlimited "'Aý-Iiefor Air Force History 1993 20050429 028 The High Road to Tokyo Bay In early 1942, Japanese military forces dominated a significant portion of the earth's surface, stretching from the Indian Ocean to the Bering Sea and from Manchuria to the Coral Sea. Just three years later, Japan surrendered, having lost most of its vast domain. Coordinated action by Allied air, naval, and ground forces attained the victory. Air power, both land- and carrier-based, played a dominant role. Understanding the Army Air Forces' role in the Asiatic-Pacific theater requires examining the con- text of Allied strategy, American air and naval operations, and ground campaigns. Without the surface conquests by soldiers and sailors, AAF fliers would have lacked bases close enough to enemy targets for effective raids. Yet, without Allied air power, these surface victories would have been impossible. The High Road to Tokyo Bay concentrates on the Army Air Forces' tactical operations in Asia and the Pacific areas during World War II. A subsequent pamphlet will cover the strategic bombardment of Japan. REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704-0188 The public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information.