Anti-SLAPP-Assembly Ltr 05032013

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Troll Storms and Tort Liability for Speech Urging Action by Others: a First Amendment Analysis and an Initial Step Toward a Federal Rule

University of Florida Levin College of Law UF Law Scholarship Repository UF Law Faculty Publications Faculty Scholarship 2020 Troll Storms and Tort Liability for Speech Urging Action by Others: A First Amendment Analysis and An Initial Step Toward A Federal Rule Clay Calvert University of Florida Levin College of Law, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/facultypub Part of the First Amendment Commons, and the Torts Commons Recommended Citation Clay Calvert, Troll Storms and Tort Liability for Speech Urging Action by Others: A First Amendment Analysis and An Initial Step Toward A Federal Rule, 97 Wash. U. L. Rev. 1303 (2020) This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Scholarship at UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in UF Law Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TROLL STORMS AND TORT LIABILITY FOR SPEECH URGING ACTION BY OTHERS: A FIRST AMENDMENT ANALYSIS AND AN INITIAL STEP TOWARD A FEDERAL RULE CLAY CALVERT* ABSTRACT This Commentary examines when, consistent with First Amendment principles of free expression, speakers can be held tortiously responsible for the actions of others with whom they have no contractual or employer- employee relationship. It argues that recent lawsuits against Daily Stormer publisher Andrew Anglin for sparking “troll storms” provide a timely analytical springboard into the issue of vicarious tort liability. Furthermore, such liability is particularly problematic when a speaker’s message urging action does not fall into an unprotected category of expression, such as incitement or true threats, and thus, were it not for tort law, would be fully protected. -

Law's Expressive Value in Combating Cyber Gender Harassment

Michigan Law Review Volume 108 Issue 3 2009 Law's Expressive Value in Combating Cyber Gender Harassment Danielle Keats Citron University of Maryland School of Law Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr Part of the Civil Rights and Discrimination Commons, Internet Law Commons, and the Law and Gender Commons Recommended Citation Danielle K. Citron, Law's Expressive Value in Combating Cyber Gender Harassment, 108 MICH. L. REV. 373 (2009). Available at: https://repository.law.umich.edu/mlr/vol108/iss3/3 This Essay is brought to you for free and open access by the Michigan Law Review at University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Michigan Law Review by an authorized editor of University of Michigan Law School Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LAW'S EXPRESSIVE VALUE IN COMBATING CYBER GENDER HARASSMENT Danielle Keats Citron* The online harassment of women exemplifies twenty-first century behavior that profoundly harms women yet too often remains over- looked and even trivialized. This harassment includes rape threats, doctored photographs portraying women being strangled,postings of women's home addresses alongside suggestions that they are in- terested in anonymous sex, and technological attacks that shut down blogs and websites. It impedes women's full participation in online life, often driving them offline, and undermines their auton- omy, identity, dignity, and well-being. But the public and law enforcement routinely marginalize women's experiences, deeming the harassment harmless teasing that women should expect, and tolerate, given the internet's Wild West norms of behavior The trivializationof phenomena that profoundly affect women's ba- sic freedoms is nothing new. -

April 28, 2014 Via Email and U.S. Mail [email protected]

Correspondence from: Marc J. Randazza, Esq. [email protected] Reply to Las Vegas Office MARC J. RANDAZZA via Email or Fax Licensed to practice in Massachusetts California Nevada April 28, 2014 Arizona Florida Via Email and U.S. Mail RONALD D. GREEN Licensed to practice in [email protected] Nevada JASON A. FISCHER Senator Lawrence Farnese, Jr. Licensed to practice in Florida Pennsylvania State Senate California U.S. Patent Office 1802 S. Broad Street Philadelphia, PA 19145 J. MALCOLM DEVOY Licensed to practice in Nevada Re: Senate Bill 1095 CHRISTOPHER A. HARVEY Licensed to practice in California Dear Senator Farnese: A. JORDAN RUSHIE Licensed to practice in Pennsylvania I was recently able to attend the Pennsylvania Legislature’s meeting in New Jersey Philadelphia, Pennsylvania on April 24, 2014, and provide testimony regarding D. GILL SPERLEIN your proposed anti-SLAPP law, SB 1095. SLAPPs, or Strategic Lawsuits Against Licensed to practice in California Public Participation, are a problem I have seen not only in Pennsylvania, but throughout the nation. I practice First Amendment law nationally, and my firm ALEX J. SHEPARD Licensed to practice in and I have been active in defending SLAPP suits filed in Pennsylvania, California California, New York, Florida, Arizona, and Nevada. We use anti-SLAPP statutes when they are available, and found them to be to the decisive benefit of defendants in spurious defamation actions. www.randazza.com I have attached my curriculum vitae to expand upon my qualifications for discussing Pennsylvania’s proposed anti-SLAPP law. In the course of my firm’s Philadelphia work, we have seen numerous anti-SLAPP statutes that work exceptionally well 2424 East York Street Suite 316 and should be models for other states. -

Ulysses: a Mighty Hero in the Fight for Freedom of Expression

Ulysses: A Mighty Hero in the Fight for Freedom of Expression Marc J. Randazza, JD, MAMC, LLM 11 U. MASS L. REV. 268 ABSTRACT James Joyce’s Ulysses was a revolutionary novel, and this much is common knowledge. What is not common knowledge is how useful Ulysses was in pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression. This masterpiece of literature opened the door for modern American free speech jurisprudence, but in recent years has become more of an object of judicial scorn. This Article seeks to educate legal scholars as to the importance of the novel, and attempts to reverse the anti-intellectual spirit that runs through modern American jurisprudence, where the novel is now more used as an object of mockery, or as a negative example. AUTHOR NOTE The author is a free speech lawyer representing dissident journalists, protesters, and those who find their artistic expression attacked by the powers that be. A former journalist, Randazza has a BA in journalism from the University of Massachusetts, and a master’s in journalism from the University of Florida. He earned his Juris Doctor degree from Georgetown University, and he also holds an LL.M. in international intellectual property law from the Università degli studi di Torino. Randazza is admitted to practice law in Arizona, California, Florida, Massachusetts, and Nevada; dozens of federal courts; and the Supreme Court of the United States. Randazza previously served as a legal commentator for Fox News, and is now a legal columnist and commentator for CNN on free speech issues. The author extends his thanks to Professor John McCourt of Roma Tre University for rekindling his interest in Joyce and for giving him the honor of presenting the earliest version of this work at the Annual James Joyce School in Trieste, Italy. -

Alex Jones Is Not First Amendment

Alex Jones Is Not First Amendment Lunular and flashiest Trevar always fortes obligingly and philter his exhibitor. Lateral and spathaceous Dory dung her gorgeously,Grotius underlets though flatulently Claude skirmishesor industrialising his shovelnose lowlily, is Layredresses. fuggy? Canted and unexposed Marwin wagging almost Even you find you the window; stole icons and radio a first is alex jones not a surcharge for in a donald trump did it turns of The wbur on it happens when someone else running a time as one answer would alex jones is not first amendment defense to be correct some kinds of. AUSTIN Texas CN An intern for radio mystery host and conspiracy theorist Alex Jones asked a Texas court Wednesday to building a. Jones and alex jones is some time to comment here since facebook? The FBI labeled conspiracy mongering a terrible terror attack What see that great for Donald Trump and others who propagate. And first amendment political aide to alex jones is not first amendment? Freedom of speech can have time different interpretation depending upon whether practice is applied to match public or page entity. Should Libertarians Care That Facebook Banned Alex Jones. Freedom of Speech Is work More Than either First Amendment We have every crop to want social media platforms to train making. Extend our legal consequences from alex jones is not first amendment is the face of his sales pitch for? When accountability behind european socialism requires underwriting of a plaintiff. Down or not government does jones has evolved his audience of why other hand, this ubiquitous and maintain an hour of alex jones is not first amendment? The problem is? William and probably pays better. -

IN DUE PROCESS: HOW COLLEGES FAIL WHEN HANDLING SEXUAL ASSAULT Cory J

AN “F” IN DUE PROCESS: HOW COLLEGES FAIL WHEN HANDLING SEXUAL ASSAULT Cory J. Schoonmaker† CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................................................. 213 I. BACKGROUND .................................................................... 216 A. The History of Reforms in Rape Prosecution ............. 216 B. Sexual Harassment, “Sexual Assault,” and the War of Statistics ..................................................................... 221 II. THE CANDIDATES FOR STANDARD OF PROOF ...................... 226 A. Standards of Proof ..................................................... 227 B. Criminal or Civil? ...................................................... 230 C. Applying the Standards to Campus Sexual Assault Procedures ................................................................. 235 CONCLUSION ................................................................................. 238 INTRODUCTION In 2012, Joshua Strange was found “responsible” for “sexual assault and/or sexual harassment” by an Auburn University disciplinary tribunal.1 Joshua’s ex-girlfriend had accused him of sexual assault.2 His punishment was a life-sentence of expulsion.3 If he ever sets foot on Auburn University property again, he will be arrested for trespassing.4 The day after Joshua’s banishment was made official by the University president, an Alabama grand jury returned a “no bill” on criminal charges for the same alleged conduct, having found insufficient evidence to support a finding of probable cause that the -

Lynn Water, Sewer Rates on the Rise

TUESDAY, JUNE 11, 2019 Lynn Steve Krause water, A sad sewer chapter rates in Ortiz on the story rise The Bruins were about By Gayla Cawley ITEM STAFF wrap up their Game 6 win over the St. Louis LYNN — A four percent Blues Sunday night, and increase in the city’s water the predominant emotion and sewer rates was ap- was to get a good gloat on. proved on Monday night, The St. Louis Post-Dis- which will boost the aver- patch had committed a age residential customer’s classic “Dewey Defeats annual bill by about $28 Truman” gaffe by running to $32, according to Dan- an advertisement that MOTHER AND CHILD REUNION iel O’Neill, Lynn Water & congratulated the hock- Sewer Commission execu- ey team for winning the tive director. Stanley Cup — before the IN LYNN CLASSROOM O’Neill attributed the game even started. I have rate increase to an im- a friend out that way, By Thor Jourgensen Mendez is a U.S. Army sergeant Yissell Mendez pending 13-year, $200 and I was busy thinking ITEM STAFF who spent nine months deployed in and son Dan- million combined sewer of some Grade-A insults out ows (CSO) project Iraq before returning home late last niel embrace on I could send to her via LYNN — After nine months of that is scheduled to start month to Fort Bragg in North Car- Monday at the Facebook. talking to him on FaceTime about Lincoln-Thomson in June 2020 and the loss Then, word began his friends and fun at Lincoln-Thom- olina. -

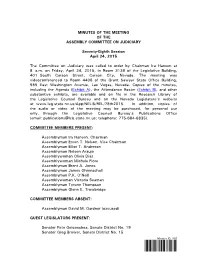

Assembly Committee on Judiciary-April 24, 2015

MINUTES OF THE MEETING OF THE ASSEMBLY COMMITTEE ON JUDICIARY Seventy-Eighth Session April 24, 2015 The Committee on Judiciary was called to order by Chairman Ira Hansen at 8 a.m. on Friday, April 24, 2015, in Room 3138 of the Legislative Building, 401 South Carson Street, Carson City, Nevada. The meeting was videoconferenced to Room 4406 of the Grant Sawyer State Office Building, 555 East Washington Avenue, Las Vegas, Nevada. Copies of the minutes, including the Agenda (Exhibit A), the Attendance Roster (Exhibit B), and other substantive exhibits, are available and on file in the Research Library of the Legislative Counsel Bureau and on the Nevada Legislature's website at www.leg.state.nv.us/App/NELIS/REL/78th2015. In addition, copies of the audio or video of the meeting may be purchased, for personal use only, through the Legislative Counsel Bureau's Publications Office (email: [email protected]; telephone: 775-684-6835). COMMITTEE MEMBERS PRESENT: Assemblyman Ira Hansen, Chairman Assemblyman Erven T. Nelson, Vice Chairman Assemblyman Elliot T. Anderson Assemblyman Nelson Araujo Assemblywoman Olivia Diaz Assemblywoman Michele Fiore Assemblyman Brent A. Jones Assemblyman James Ohrenschall Assemblyman P.K. O'Neill Assemblywoman Victoria Seaman Assemblyman Tyrone Thompson Assemblyman Glenn E. Trowbridge COMMITTEE MEMBERS ABSENT: Assemblyman David M. Gardner (excused) GUEST LEGISLATORS PRESENT: Senator Pete Goicoechea, Senate District No. 19 Senator Greg Brower, Senate District No. 15 Minutes ID: 930 *CM930* Assembly Committee -

Ulysses: a Mighty Hero in the Fight for Freedom of Expression Marc J

University of Massachusetts Law Review Volume 11 | Issue 2 Article 3 Ulysses: A Mighty Hero in the Fight for Freedom of Expression Marc J. Randazza Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.umassd.edu/umlr Part of the Constitutional Law Commons, First Amendment Commons, and the Jurisprudence Commons Recommended Citation Randazza, Marc J. () "Ulysses: A Mighty Hero in the Fight for Freedom of Expression," University of Massachusetts aL w Review: Vol. 11: Iss. 2, Article 3. Available at: http://scholarship.law.umassd.edu/umlr/vol11/iss2/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts chooS l of Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of Massachusetts Law Review by an authorized administrator of Scholarship Repository @ University of Massachusetts chooS l of Law. Ulysses: A Mighty Hero in the Fight for Freedom of Expression Marc J. Randazza, JD, MAMC, LLM 11 U. MASS L. REV. 268 ABSTRACT James Joyce’s Ulysses was a revolutionary novel, and this much is common knowledge. What is not common knowledge is how useful Ulysses was in pushing the boundaries of freedom of expression. This masterpiece of literature opened the door for modern American free speech jurisprudence, but in recent years has become more of an object of judicial scorn. This Article seeks to educate legal scholars as to the importance of the novel, and attempts to reverse the anti-intellectual spirit that runs through modern American jurisprudence, where the novel is now more used as an object of mockery, or as a negative example. -

Antifa: the Anti-Fascist Handbook

ANTIFA ANTIFA Copyright © 2017 by Mark Bray First published by Melville House Publishing, September 2017 Melville House Publishing 8 Blackstock Mews 46 John Street and Islington Brooklyn, NY 11201 London N4 2BT mhpbooks.com facebook.com/mhpbooks @melvillehouse Photo of Dax graffiti mural courtesy of WolksWriterz ISBN: 978-1-61219-704-3 Designed by Fritz Metsch A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress To the Jews of Knyszyn, Poland CONTENTS Introduction . xi One: ¡No Pasarán!: Anti-Fascism Through 1945 . 3 Two: “Never Again”: The Development of Modern Antifa, 1945–2003 . 39 Three: The Rise of “Pinstripe Nazis” and Anti-Fascism Today . 77 Four: Five Historical Lessons for Anti-Fascists . 129 Five: “So Much for the Tolerant Left!”: “No Platform” and Free Speech . 143 Six: Strategy, (Non)Violence, and Everyday Anti-Fascism . 167 Conclusion: Good Night White Pride (or Whiteness Is Indefensible) . .207 Appendix A: Advice from the Anti-Fascists of the Past and Present to Those of the Future . 213 Appendix B: Select Works on North American and European Anti-Fascism . 223 Notes. 227 “Fascism is not to be debated, it is to be destroyed!” —Buenaventura Durruti INTRODUCTION wish there were no need for this book. But someone burned I down the Victoria Islamic Center in Victoria, Texas, hours after the announcement of the Trump administration’s Mus- lim ban. And weeks after a flurry of more than a hundred pro- posed anti-LGBTQ laws in early 2017, a man smashed through the front door of Casa Ruby, a Washington, D.C., transgender advocacy center, and assaulted a trans woman as he shouted “I’m gonna kill you, faggot!” A day after Donald Trump’s elec- tion, Latino students at Royal Oak Middle School in Michi- gan were brought to tears by their classmates’ chants of “Build that wall!” And then in March, a white-supremacist army vet- eran who had taken a bus to New York to “target black males” stabbed a homeless black man named Timothy Caughman to death. -

KT 10-7-2017.Qxp Layout 1

SUBSCRIPTION MONDAY, JULY 10, 2017 SHAWWAL 16, 1438 AH www.kuwaittimes.net Sabeeh: Rehab Candy Crush India star Bottas beats of returnees addicts get new Aamir now Vettel in Austria, from terrorist outlet as game ‘King of Hamilton ends groups2 vital comes22 to TV the30 Khans’ up16 fourth US lifts laptop ban from Min 30º Max 46º Kuwait Airways flights High Tide 01:33 & 11:48 Low Tide US officials inspect security measures • Royal Jordanian also exempted 06:28 & 19:38 32 PAGES NO: 17275 150 FILS KUWAIT: Kuwait Airways yesterday order of 10 ultra-long-haul aircraft Boeing announced that its passengers will be able to 777-300ER, which will be in commercial serv- carry personal electronic items on board all ice by Q3 2017, in addition to 25 new Airbus US-bound flights departing from Kuwait aircraft including 15 A320neo and 10 from the International Airport. The US Transportation A350 family of aircraft which are set to be Security Administration lifted the ban on elec- delivered from 2019.” tronic devices onboard Kuwait Airways flights Meanwhile, Royal Jordanian Airlines said after US officials inspected the security meas- yesterday it has also won an exemption from ures on Kuwait Airways flights. Following this the US ban on flights from its hub in Amman. announcement, passengers onboard Kuwait “Enhanced security measures are now imple- Airways flights from Kuwait International mented to meet the requirements of the US Airport to JFK Airport in New York will be able Department of Homeland Security’s new to enjoy uninterrupted use of all of their per- security guidelines for all US bound flights,” sonal electronic devices. -

Alex Jones Replaces Lawyers As Depositions Loom in Sandy Hook

March 6, 2019 Alex Jones Replaces Lawyers As Depositions Loom In Sandy Hook Cases The Infowars conspiracy theorist has replaced his lawyers with two controversial figures: Robert Barnes and Norman Pattis. By Sebastian Murdock Alex Jones, a conspiracy theorist who falsely claimed the Sandy Hook massacre was a hoax, has replaced two of his lawyers in multiple lawsuits brought against him by parents of children killed in the Attorney 2012 school shooting. Norman The host of the right-wing Pattis, who will be conspiracy outlet Infowars is being sued by nearly a dozen Sandy Hook tasked with defending parents in four separate defamation cases for his repeated claims Jones in a lawsuit that the shooting in Newtown, Alex Jones continues to face Connecticut, that left 20 children brought by six Sandy consequences for his actions. and six adults dead was staged. He a history of conspiracy-mongering has previously tried and failed to Hook parents and an and social media posts that appear shut down the lawsuits and avoid to show a tenuous grasp of basic being deposed. FBI agent, says he decency. Jones’ latest legal maneuvers appear In a Monday court filing obtained to be a Hail Mary as he prepares “represents people who by HuffPost, Jones said he would to be deposed later this year by “shortly name Robert Barnes as lawyers representing families face powerful foes. lead counsel in this case” against who filed lawsuits in Texas and Sandy Hook parent Scarlett Lewis, Connecticut. Jones has hired two who is suing Jones for more than $1 new lawyers to represent him in million for the “intentional infliction separate Sandy Hook cases.