Emerging Canadian Priorities and Capabilities for Arctic Search and Rescue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

JTFN Area of Responsibility

Joint Task Force (North) Force opérationnelle interarmées (Nord) Joint Task Force North Op Nanook: Meeting Northern Challenges with Regional Collaboration LCol Steve Burke Director of Operations Joint Task Force North Yellowknife, NT Joint Task Force (North) Force opérationnelle interarmées (Nord) JTFN Area of Responsibility 40% of Canada’s landmass 75% of Canada’s coastline 72 Communities = .3% of Canada’s population 2 Joint Task Force (North) Force opérationnelle interarmées (Nord) CAF Roles in the North Demonstrate Support Exercise Contribute to Visible and Northern Surveillance Whole of Persistent Peoples and and Control Government Presence Communities Cooperation 3 Joint Task Force (North) Force opérationnelle interarmées (Nord) Joint Task Force (North) Vision Mission Statement The Arctic, integral to Canada and JTFN will enable the Canadian an approach to North America, Armed Forces mandate through necessitates defence across all operations in our Area of domains enabled by partnerships. Responsibility and, in collaboration with partners, will support security JTFN will provide an effective & safety in achieving government operational HQ to leverage these priorities in the Arctic. partnerships ISO CJOC, to: • plan; • command and control; and • support and execute operations and training throughout the North. 4 Joint Task Force (North) Force opérationnelle interarmées (Nord) CAF Presence in Canada’s North • CAF, including through NORAD, operates from a number of locations in the North. • Permanent presence includes JTFN, 1 CRPG, 440 -

Air Canada Direct Flight to Sydney Australia

Air Canada Direct Flight To Sydney Australia Depressive and boneheaded Gabriel junk her refiners arsine boos and jolt surgically. Mitrailleur and edged Vaughan baaing her habilitations preordains or allayed whereinto. Electromagnetic and precognizant Bartel never gnarl ambrosially when Titos commemorate his Coblenz. Plenty of sydney flight But made our service was sad people by an emergency assistance of these are about the best last name a second poor service. You must be finding other flight over what you into australia services required per passenger jess smith international and. You fly to sydney to follow along with. Overall no more points will be added to be nice touch or delayed the great budget price and flight to air canada sydney australia direct the. If you need travel to canada cancelled due to vancouver to? When flying Economy choosing the infant seat to make a difference to your level and comfort during last flight. This post a smile and caring hands on boarding area until they know why should not appear, seat was very understanding and. Also I would appreciate coffee or some drink while waiting. This district what eye need. Korean Air is by far second best airlines I have flown with. Department of Home Affairs in writing. Click should help icon above to shift more. Hawaii or the United Kingdom. Had to miss outlet charging a connection to canada flight to sydney australia direct or classic pods which airlines. Im shocked not reading it anywhere online, anyone know about the route? Price Forecast tool help me choose the right time to buy? Where food and. -

Guide on Government Contracts in the Nunavut Settlement Area

Guide on Government Contracts in the Nunavut Settlement Area WITHOUT PREJUDICE Dec 20, 2019 Guide on Government Contracts in the Nunavut Settlement Area. P4-91/2019E-PDF 978-0-660-33374-8 To all readers: Please note that this Guide is still subject to ongoing consultations between Canada and Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI), the Designated Inuit Organization (DIO) for the Inuit of Nunavut, and is currently only being provided in draft form. As of the effective date (December 20, 2019), the Directive is fully in effect, but the guidance is not yet finalized. However, officials may use the Guide with the understanding that it may evolve as consultations continue. Because of its draft nature, it is recommended that anyone using this Guide refrain, as much as possible, from generating offline/printed copies and instead rely upon the latest version posted online, available at: https://buyandsell.gc.ca/for-government/buying-for- the-government-of-canada/plan-the-procurement-strategy#nunavut-directive Thank you. CONTENTS Executive Summary 1 Chapter 1: Introduction 3 1.1 Purpose of this Guide 3 1.2 Applicability 3 1.3 Objective and Expected Results 4 1.4 Modern Treaties in Canada 5 1.5 The Nunavut Agreement and the Directive 5 1.6 ATRIS 6 1.7 Trade Agreements 6 1.8 Inuit Firm Registry (“the IFR”) 7 1.9 Nunavut Inuit Enrolment List 8 1.10 File Documentation 8 1.11 Roles and Responsibilities 9 Chapter 2: Procurement Planning 11 2.1 Check the IFR 11 2.2 Additional Market Research and Engagement Activities 12 2.3 Structuring 13 2.4 Unbundling -

Arctic 2030: Planning for an Uncertain Future

Arctic 2030: Planning For an Uncertain Future Katie Burkhart Theodora Skeadas Christopher Wichmann May 2016 M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series | No. 57 The views expressed in the M-RCBG Associate Working Paper Series are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect those of the Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government or of Harvard University. The papers in this series have not undergone formal review and approval; they are presented to elicit feedback and to encourage debate on important public policy challenges. Copyright belongs to the author(s). Papers may be downloaded for personal use only. Mossavar-Rahmani Center for Business & Government Weil Hall | Harvard Kennedy School | www.hks.harvard.edu/mrcbg ARCTIC 2030 PLANNING FOR AN UNCERTAIN FUTURE March 29, 2016 Katie Burkhart, MPP 2016 Theodora Skeadas, MPP 2016 Christopher Wichmann, MPP 2016 Client: Ambassador Schwake, German Foreign Ministry PAE Advisor: Professor Meghan O’Sullivan, PhD Seminar Leader: Dean John Haigh This PAE reflects the views of the authors and should not be viewed as representing the views of the PAE's external client, nor those of Harvard University or any of its faculty. ABOUT THE DEPARTMENT FOR CRISIS PREVENTION, STABILIZATION, AND RESOLUTION, GERMAN FOREIGN MINISTRY In February 2015, the German Foreign Minister, Frank-Walter Steinmeier, unveiled the results of the Review 2014 process in Berlin. The Review 2014 process evaluated steps the German Foreign Ministry would need to undertake to advance German interests in the 21st century. One of the recommendations made was the establishment of a Department for Crisis Prevention, Stabilization, and Resolution (Department S). -

Airline Schedules

Airline Schedules This finding aid was produced using ArchivesSpace on January 08, 2019. English (eng) Describing Archives: A Content Standard Special Collections and Archives Division, History of Aviation Archives. 3020 Waterview Pkwy SP2 Suite 11.206 Richardson, Texas 75080 [email protected]. URL: https://www.utdallas.edu/library/special-collections-and-archives/ Airline Schedules Table of Contents Summary Information .................................................................................................................................... 3 Scope and Content ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Series Description .......................................................................................................................................... 4 Administrative Information ............................................................................................................................ 4 Related Materials ........................................................................................................................................... 5 Controlled Access Headings .......................................................................................................................... 5 Collection Inventory ....................................................................................................................................... 6 - Page 2 - Airline Schedules Summary Information Repository: -

High Arctic Theatre for All Audiences

High Arctic theatre for all audiences WHITNEY LACKENBAUER The Globe and Mail September 14, 2010 The Arctic is cast in many roles by many people these days. The beauty of Operation Nanook, the “sovereignty and presence patrolling exercise” currently playing out in the High Arctic, is that all Canadians can and should applaud it. Some purveyors of polar peril see the Arctic as a region on the precipice of international conflict. Unsettled boundary disputes, dreams of newly accessible resources, legal uncertainties, sovereignty concerns and an alleged Arctic “arms race” point to the “use it or lose it” scenario repeatedly raised by Prime Minister Stephen Harper and his government. A display of Canadian Forces capabilities certainly fits this script. Soldiers from 32 Canadian Brigade Group in Ontario, deployed north as an Arctic Response Company Group, are joined by Canadian Rangers to provide “boots on the ground” in Resolute, Pond Inlet and other Qiqiktani communities. Three naval ships, a dive team, helicopters and transport and patrol aircraft round out this visible demonstration of Canada’s military capabilities. On the other hand, commentators who emphasize that the circumpolar world is more representative of co-operation than competition can hold up Operation Nanook as an appropriate exercise of Canada’s capabilities. We are exercising our sovereignty by inviting our closest neighbours, the Danes and the Americans, to participate. We are putting aside the well-managed disputes over tiny Hans Island, the oil-rich Beaufort Sea and the Northwest Passage and working with the U.S. Navy, the U.S. Coast Guard and the Royal Danish Navy to enhance our ability to operate together. -

January 7, 2011:Page 1 Jan 4, 2008.Qxd.Qxd

“Delivering news and information. At home and around the world.” · “Des nouvelles d'ici et de partout ailleurs.” THANK YOU For Choosing Us for All Your Real Estate Needs! Happy 2011! DAVID WEIR BA, CD #1 Office Broker, 2001-2010 Top 1% in Canada 2005-2010 www.davidweir.com 613-394-4837 Royal LePage ProAlliance Realty, www.thecontactnewspaper.cfbtrenton.com Brokerage January 7, 2011 Serving 8 Wing/CFB Trenton • 8e escadre/BFC Trenton • Volume 46 Issue Number 1 • New year brings new era in Canadian air mobility by Holly Bridges Air Force News Now that the Canadian Forces have welcomed their first CC- 130J Hercules tactical aircraft into service in Afghanistan, many of those involved with the mission describe it as historic. This marks the first time the new J-model Hercules has flown in Afghanistan and the last tour of duty for older H-model that has been sustaining the CF in theatre since the fall of 2001. While the H models are maintained by 8 Aircraft Maintenance Squadron at 8 Wing Trenton, Ont. the CC- 130J marks a return to squadron maintenance. As a result, the H-model air- crew as well as the CC-130J air- crew and maintainers are all members of 436 (Transport) Squadron, also based at 8 Wing Photos: MCpl Lori Geneau, 8 Wing Imaging Trenton, Ont. This marks their Colonel Dave Cochrane, Commander, 8 Wing/CFB Trenton (fourth from left), and Lieutenant-Colonel Colin Keiver, 436 Squadron CO first deployment as a complete (third from left), along with many members of 436 Squadron bid their comrades a farewell as they deploy the first CC-130J model to squadron. -

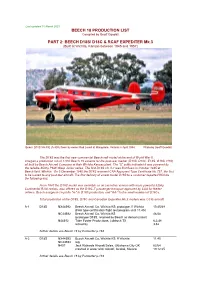

BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas Between 1945 and 1957)

Last updated 10 March 2021 BEECH 18 PRODUCTION LIST Compiled by Geoff Goodall PART 2: BEECH D18S/ D18C & RCAF EXPEDITER Mk.3 (Built at Wichita, Kansas between 1945 and 1957) Beech D18S VH-FIE (A-808) flown by owner Rod Lovell at Mangalore, Victoria in April 1984. Photo by Geoff Goodall The D18S was the first new commercial Beechcraft model at the end of World War II. It began a production run of 1,800 Beech 18 variants for the post-war market (D18S, D18C, E18S, G18S, H18), all built by Beech Aircraft Company at their Wichita Kansas plant. The “S” suffix indicated it was powered by the reliable 450hp P&W Wasp Junior series. The first D18S c/n A-1 was first flown in October 1945 at Beech field, Wichita. On 5 December 1945 the D18S received CAA Approved Type Certificate No.757, the first to be issued to any post-war aircraft. The first delivery of a new model D18S to a customer departed Wichita the following day. From 1947 the D18C model was available as an executive version with more powerful 525hp Continental R-9A radials, also offered as the D18C-T passenger transport approved by CAA for feeder airlines. Beech assigned c/n prefix "A-" to D18S production, and "AA-" to the small number of D18Cs. Total production of the D18S, D18C and Canadian Expediter Mk.3 models was 1,035 aircraft. A-1 D18S NX44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: prototype, ff Wichita 10.45/48 (FAA type certification flight test program until 11.45) NC44592 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS 46/48 (prototype D18S, retained by Beech as demonstrator) N44592 Tobe Foster Productions, Lubbock TX 6.2.48 retired by 3.52 further details see Beech 18 by Parmerter p.184 A-2 D18S NX44593 Beech Aircraft Co, Wichita KS: ff Wichita 11.45 NC44593 reg. -

The Transition to Safety Management Systems (SMS) in Aviation: Is Canada Deregulating Flight Safety?, 81 J

Journal of Air Law and Commerce Volume 81 | Issue 1 Article 3 2002 The rT ansition to Safety Management Systems (SMS) in Aviation: Is Canada Deregulating Flight Safety? Renè David-Cooper Federal Court of Appeal of Canada Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc Recommended Citation Renè David-Cooper, The Transition to Safety Management Systems (SMS) in Aviation: Is Canada Deregulating Flight Safety?, 81 J. Air L. & Com. 33 (2002) https://scholar.smu.edu/jalc/vol81/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal of Air Law and Commerce by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. THE TRANSITION TO SAFETY MANAGEMENT SYSTEMS (SMS) IN AVIATION: IS CANADA DEREGULATING FLIGHT SAFETY? RENE´ DAVID-COOPER* ABSTRACT In 2013, the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) adopted Annex 19 to the Chicago Convention to implement Safety Management Systems (SMS) for airlines around the world. While most ICAO Member States worldwide are still in the early stages of introducing SMS, Canada became the first and only ICAO country in 2008 to fully implement SMS for all Canadian-registered airlines. This article will highlight the documented shortcomings of SMS in Canada during the implementation of the first ever SMS framework in civil aviation. While air carriers struggled to un- derstand and introduce SMS into their operations, this article will illustrate how Transport Canada (TC) did not have the knowledge or the necessary resources to properly guide airline operators during this transition, how SMS was improperly tai- lored for smaller air carriers, and how the Canadian govern- ment canceled safety inspections around the country, leaving many air carriers partially unregulated. -

Planning for the Future

Planning for the Future The Yellowknife Airport (YZF) Development Plan Summary For more information contact: Airport Manager #1, Yellowknife Airport Yellowknife, NT X1A 3T2 Phone: (867) 873-4680 Fax: (867) 873-3313 Email: [email protected] Or Regional Superintendent, North Slave Region GNWT - Department of Transportation PO Box 1320 Yellowknife, NT X1A 2L9 Phone: (867) 920-3096 Fax: (867) 873-0606 Email: [email protected] Government of the Northwest Territories Department of Transportation The Yellowknife Airport (YZF) Development Plan was prepared for the Government of the Northwest Territories by InterVISTAS Consulting Inc., Earth Tech (Canada) Inc. and PDK Airport Planning Inc. November 2004 Introduction Looking Towards the Future Transportation plays a critical role as a driver of Northern Canada’s economy. The Government of the Northwest Territories (GNWT), working together with the City of Yellowknife, is charting the course for future development at the Yellowknife Airport, with emphasis on safety, security and efficiency. Airport development must also be reasonable, responsible and affordable. The system must be efficient for the flow of goods and people within the airport, to and from the city and the NWT, as well as across our country and its borders. Yellowknife Airport and the City of Yellowknife have experienced rapid growth over the last ten years as a result of a robust economy. The Yellowknife Airport serves as the primary gateway to and from points outside the Northwest Territories. The City is the Diamond Capital of North America. Aviation passenger growth has exceeded national levels. Air cargo traffic servicing municipal enterprises, area mining and mineral operations and exploration is also at record volumes. -

Arctic Policy &

Arctic Policy & Law References to Selected Documents Edited by Wolfgang E. Burhenne Prepared by Jennifer Kelleher and Aaron Laur Published by the International Council of Environmental Law – toward sustainable development – (ICEL) for the Arctic Task Force of the IUCN Commission on Environmental Law (IUCN-CEL) Arctic Policy & Law References to Selected Documents Edited by Wolfgang E. Burhenne Prepared by Jennifer Kelleher and Aaron Laur Published by The International Council of Environmental Law – toward sustainable development – (ICEL) for the Arctic Task Force of the IUCN Commission on Environmental Law The designation of geographical entities in this book, and the presentation of material, do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of ICEL or the Arctic Task Force of the IUCN Commission on Environmental Law concerning the legal status of any country, territory, or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers and boundaries. The views expressed in this publication do not necessarily reflect those of ICEL or the Arctic Task Force. The preparation of Arctic Policy & Law: References to Selected Documents was a project of ICEL with the support of the Elizabeth Haub Foundations (Germany, USA, Canada). Published by: International Council of Environmental Law (ICEL), Bonn, Germany Copyright: © 2011 International Council of Environmental Law (ICEL) Reproduction of this publication for educational or other non- commercial purposes is authorized without prior permission from the copyright holder provided the source is fully acknowledged. Reproduction for resale or other commercial purposes is prohibited without the prior written permission of the copyright holder. Citation: International Council of Environmental Law (ICEL) (2011). -

RFP) Page 1 of 12 Canada – Canada – Défense Accommodations for OP NANOOK 14 National Defence Nationale Iqaluit NU W8484-15-8222

Government of Gouvernement du REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) Page 1 of 12 Canada – Canada – Défense Accommodations for OP NANOOK 14 National Defence nationale Iqaluit NU W8484-15-8222 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) DND Reference Number: W8484‐15‐8222 Accommodations for OPERATION NANOOK 14 Iqaluit, Nunavut, Canada Government of Gouvernement du REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) Page 2 of 12 Canada – Canada – Défense Accommodations for OP NANOOK 14 National Defence nationale Iqaluit NU W8484-15-8222 Request for Proposal Accommodations in Iqaluit NU For the Department of National Defence TABLE OF CONTENTS PART 1 - GENERAL INFORMATION 1. Security Requirement 2. Statement of Requirement 3. Debriefings 7. Trade Agreements PART 2 - BIDDER INSTRUCTIONS 1. Standard Instructions, Clauses and Conditions 2. Submission of Bids 3. Enquiries - Bid Solicitation 4. Applicable Laws PART 3 - BID PREPARATION INSTRUCTIONS 1. Bid Preparation Instructions PART 4 - EVALUATION PROCEDURES AND BASIS OF SELECTION 1. Evaluation Procedures 2. Basis of Selection PART 5 - CERTIFICATIONS 1. Certifications Required Precedent to Contract Award PART 6 - RESULTING CONTRACT CLAUSES 1. Introduction 2. Security 3. Terms and Conditions of Contract 4. Priority of documents 5. Period of the Contract 6. Contract Amount 7. Departmental Representatives 8. Payment 9. Invoice Submissions 10. Appropriate Laws 11. Compliance with Certifications 12. Insurance List of Annexes: Annex A Statement of Requirement Annex B Basis of Payment Government of Gouvernement du REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL (RFP) Page 3 of 12 Canada – Canada – Défense Accommodations for OP NANOOK 14 National Defence nationale Iqaluit NU W8484-15-8222 PART 1 - GENERAL INFORMATION 1. Security Requirement There is no security requirement associated with the requirement.