St Augustine of Hippo Biography Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Nuremberg Chronicle Recycles a Pre-Christian Idea Paul Gross*

ERROR TOWARDS JUDGEMENT. HOW THE NUREMBERG CHRONICLE RECYCLES A PRE-CHRISTIAN IDEA PAUL GROSS* Resumo: Ainda que firmemente baseada numa doutrina cristã, aCrónica de Nuremberga de 1493 abre com uma enumeração de ideias opostas relativamente à origem do mundo e do Homem. Esta primeira passagem é, porém, desde logo rotulada como sendo um erro. Contudo, enquanto o narrador estabelece uma verdade universal, outro erro surge proeminentemente como parte da dimensão factual da crónica. Através da análise intermedial dos textos e de xilogravuras, o presente texto pretende investigar então a forma como este incu- nábulo expõe uma variedade de inverdades com o eventual intuito de integrar uma destas na sua ideologia. Palavras-chave: Crónica do mundo; Incunábulo; Intermedialidade; Early New High German. Abstract: Although firmly grounded in Christian doctrine, the 1493Nuremberg Chronicle opens with an enu- meration of conflicting ideas regarding the origin of the world and of mankind. This initial passage is quickly and effectively done away with by being labelled erroneous. However, while the narrator continues to estab- lish a universal truth, one of the errors reappears, prominently, as part of the chronicle’s facticity. Through the intermedial analysis of texts and woodcuts the paper investigates how the incunable exposes a multitude of falsehoods to eventually integrate one of them into its ideology. Keywords: World chronicle; Incunable; Intermediality; Early New High German. Although firmly grounded in Christian doctrine, the 1493 Nuremberg Chronicle opens with an enumeration of conflicting ideas regarding the origin of the world and of man- kind. This initial passage is quickly and effectively done away with by being labelled erro- neous. -

FINDING AID to the RARE BOOK LEAVES COLLECTION, 1440 – Late 19/20Th Century

FINDING AID TO THE RARE BOOK LEAVES COLLECTION, 1440 – Late 19/20th Century Purdue University Libraries Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center 504 West State Street West Lafayette, Indiana 47907-2058 (765) 494-2839 http://www.lib.purdue.edu/spcol © 2013 Purdue University Libraries. All rights reserved. Processed by: Kristin Leaman, August 27, 2013 Descriptive Summary Title Rare Book Leaves collection Collection Identifier MSP 137 Date Span 1440 – late 19th/early 20th Century Abstract The Rare Book Leaves collection contains leaves from Buddhist scriptures, Golden Legend, Sidonia the Sorceress, Nuremberg Chronicle, Codex de Tortis, and an illustrated version of Wordsworth’s poem Daffodils. The collection demonstrates a variety of printing styles and paper. This particular collection is an excellent teaching tool for many classes in the humanities. Extent 0.5 cubic feet (1 flat box) Finding Aid Author Kristin Leaman, 2013 Languages English, Latin, Chinese Repository Virginia Kelly Karnes Archives and Special Collections Research Center, Purdue University Libraries Administrative Information Location Information: ASC Access Restrictions: Collection is open for research. Acquisition It is very possible Eleanore Cammack ordered these Information: rare book leaves from Dawson’s Book Shop. Cammack served as a librarian in the Purdue Libraries. She was originally hired as an order assistant in 1929. By 1955, she had become the head of the library's Order Department with a rank of assistant professor. Accession Number: 20100114 Preferred Citation: MSP 137, Rare Book Leaves collection, Archives and Special Collections, Purdue University Libraries Copyright Notice: Purdue Libraries 7/7/2014 2 Related Materials MSP 136, Medieval Manuscript Leaves collection Information: Collection of Tycho Brahe engravings Collection of British Indentures Palm Leaf Book Original Leaves from Famous Books Eight Centuries 1240 A.D.-1923 A.D. -

1 a Place Is Carefully Constructed: Reading the Nuremberg Cityscape

A Place is Carefully Constructed: Reading the Nuremberg Cityscape in the Nuremberg Chronicle Kendra Grimmett A Sense of Place May 3, 2015 In 1493 a group of Nuremberg citizens published the Liber Chronicarum, a richly illustrated printed book that recounts the history of the world from Creation to what was then present day.1 The massive tome, which contains an impressive 1,809 woodcut prints from 645 different woodblocks, is also known as the Nuremberg Chronicle. This modern English title, which alludes to the book’s city of production, misleadingly suggests that the volume only records Nuremberg’s history. Even so, I imagine that the men responsible for the book would approve of this alternate title. After all, from folios 99 verso through 101 recto, the carefully constructed visual and textual descriptions of Nuremberg and its inhabitants already unabashedly favor the makers’ hometown. Truthfully, it was common in the final decades of the fifteenth century for citizens’ civic pride and local allegiance to take precedence over their regional or national identification.2 This sentiment is strongly stated in the city’s description, which directly follows the large Nuremberg print spanning folios 99 verso and 100 recto (fig. 1). The Chronicle specifies that although there was doubt whether Nuremberg was Franconian or Bavarian, “Nurembergers neither wished to be 1 Scholarship on the Nuremberg Chronicle is extensive. See, for instance: Stephanie Leitch, “Center the Self: Mapping the Nuremberg Chronicle and the Limits of the World,” in Mapping Ethnography in Early Modern Germany: New Worlds in Print Culture (Basingstoke; New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2010), 17-35; Jeffrey Chipps Smith, “Imaging and Imagining Nuremberg,” in Topographies of the Early Modern City, ed. -

Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate

Fordham University DigitalResearch@Fordham Faculty Publications Jewish Studies 2020 Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs Part of the History Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fordham University, "Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate" (2020). Faculty Publications. 2. https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jewish Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Media Technology & The Dissemination of Hate November 15th, 2019-May 31st 2020 O’Hare Special Collections Fordham University & Center for Jewish Studies Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Highlights from the Fordham Collection November 15th, 2019-May 31st, 2020 Curated by Sally Brander FCRH ‘20 Clare McCabe FCRH ‘20 Magda Teter, The Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies with contributions from Students from the class HIST 4308 Antisemitism in the Fall of 2018 and 2019 O’Hare Special Collections Walsh Family Library, Fordham University Table of Contents Preface i Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate 1 Christian (Mis)Interpretation and (Mis)Representation of Judaism 5 The Printing Press and The Cautionary Tale of One Image 13 New Technology and New Opportunities 22 -

Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations Spring 2010 Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection Jason Skirry University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the History of Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Skirry, Jason, "Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection" (2010). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 179. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/179 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/179 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Malebranche's Augustinianism and the Mind's Perfection Abstract This dissertation presents a unified interpretation of Malebranche’s philosophical system that is based on his Augustinian theory of the mind’s perfection, which consists in maximizing the mind’s ability to successfully access, comprehend, and follow God’s Order through practices that purify and cognitively enhance the mind’s attention. I argue that the mind’s perfection figures centrally in Malebranche’s philosophy and is the main hub that connects and reconciles the three fundamental principles of his system, namely, his occasionalism, divine illumination, and freedom. To demonstrate this, I first present, in chapter one, Malebranche’s philosophy within the historical and intellectual context of his membership in the French Oratory, arguing that the Oratory’s particular brand of Augustinianism, initiated by Cardinal Bérulle and propagated by Oratorians such as Andre Martin, is at the core of his philosophy and informs his theory of perfection. Next, in chapter two, I explicate Augustine’s own theory of perfection in order to provide an outline, and a basis of comparison, for Malebranche’s own theory of perfection. -

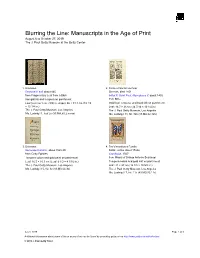

Blurring the Line: Manuscripts in the Age of Print August 6 to October 27, 2019 the J

Blurring the Line: Manuscripts in the Age of Print August 6 to October 27, 2019 The J. Paul Getty Museum at the Getty Center 6 6 1. Unknown 2. Circle of Stefan Lochner AGE_ PRINT Detached Leaf, about 845 German, died 1451 AGE_ from Fragmentary Leaf from a Bible PRINT Initial P: Saint Paul, Maccabees II, about 1450 Iron gall ink and tempera on parchment from Bible Leaf (cut into 1 cm. (3/8) in. strips): 46 × 31.1 cm (18 1/8 Gold leaf, tempera, and black ink on parchment × 12 1/4 in.) Leaf: 36.7 × 26 cm (14 7/16 × 10 1/4 in.) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Ms. Ludwig I 1, leaf 2v (83.MA.50.2.verso) Ms. Ludwig I 13, fol. 326 (83.MA.62.326) 6 6 3. Unknown 4. Fra Vincentius a Fundis AGE_ PRINT Decorated Initial R, about 1528-30 Italian, active about 1560s AGE_ from Getty Epistles PRINT Crucifixion, 1567 Tempera colors and gold paint on parchment from Missal of Bishop Antonio Scarampi Leaf: 16.5 × 10.3 cm (Leaf: 6 1/2 × 4 1/16 in.) Tempera colors and gold leaf on parchment The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Leaf: 41 × 27 cm (16 1/8 × 10 5/8 in.) Ms. Ludwig I 15, fol. 3v (83.MA.64.3v) The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles Ms. Ludwig V 7, fol. 11v (83.MG.82.11v) July 8, 2019 Page 1 of 5 Additional information about some of these works of art can be found by searching getty.edu at http://www.getty.edu/art/collection/ © 2019 J. -

Venetian Capital, German Technology and Renaissance Culture in the Later Fifteenth Century

Lowry, M. Venetian Capital, German Technology and Renaissance Culture in the Later Fifteenth Century pp. 1-13 Lowry, M., (1988) "Venetian Capital, German Technology and Renaissance Culture in the Later Fifteenth Century", Renaissance studies, 2, 1, pp.1-13 Staff and students of University of Warwick are reminded that copyright subsists in this extract and the work from which it was taken. This Digital Copy has been made under the terms of a CLA licence which allows you to: • access and download a copy; • print out a copy; Please note that this material is for use ONLY by students registered on the course of study as stated in the section below. All other staff and students are only entitled to browse the material and should not download and/or print out a copy. This Digital Copy and any digital or printed copy supplied to or made by you under the terms of this Licence are for use in connection with this Course of Study. You may retain such copies after the end of the course, but strictly for your own personal use. All copies (including electronic copies) shall include this Copyright Notice and shall be destroyed and/or deleted if and when required by University of Warwick. Except as provided for by copyright law, no further copying, storage or distribution (including by e-mail) is permitted without the consent of the copyright holder. The author (which term includes artists and other visual creators) has moral rights in the work and neither staff nor students may cause, or permit, the distortion, mutilation or other modification of the work, or any other derogatory treatment of it, which would be prejudicial to the honour or reputation of the author. -

Sauterdivineansamplepages (Pdf)

The Decline of Space: Euclid between the Ancient and Medieval Worlds Michael J. Sauter División de Historia Centro de Investigación y Docencia Económicas, A.C. Carretera México-Toluca 3655 Colonia Lomas de Santa Fe 01210 México, Distrito Federal Tel: (+52) 55-5727-9800 x2150 Table of Contents List of Illustrations ............................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgments .............................................................................................................. v Preface ............................................................................................................................... vi Introduction: The divine and the decline of space .............................................................. 1 Chapter 1: Divinus absconditus .......................................................................................... 2 Chapter 2: The problem of continuity ............................................................................... 19 Chapter 3: The space of hierarchy .................................................................................... 21 Chapter 4: Euclid in Purgatory ......................................................................................... 40 Chapter 5: The ladder of reason ........................................................................................ 63 Chapter 6: The harvest of homogeneity ............................................................................ 98 Conclusion: The -

Predication and the Problem of Universals Catherine Legg

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Research Commons@Waikato Philosophical Papers Vol. 30, No. 2 (July 2001): 117-143 Predication and the Problem of Universals Catherine Legg Abstract: This paper contrasts the scholastic realists of David Armstrong and Charles Peirce. It is argued that the so-called 'problem of universals' is not a problem in pure ontology (concerning whether universals exist) as Armstrong construes it to be. Rather, it extends to issues concerning which predicates should be applied where, issues which Armstrong sets aside under the label of 'semantics', and which from a Peircean perspective encompass even the fundamentals of scientific methodology. It is argued that Peir ce's scholastic realism not only presents a more nuanced ontology (distinguishing the existent front the real) but also provides more of a sense of why realism should be a position worth fighting for. ... a realist is simply one who knows no more recondite reality than that which is represented in a true representation. C.S. Peirce Like many other philosophical problems, the grandly-named 'Problem of Universals' is difficult to define without begging the question that it raises. Laurence Goldstein, however, provides a helpful hands-off denotation of the problem by noting that it proceeds from what he calls The Trivial Obseruation:2 The observation is the seemingly incontrovertible claim that, 'sometimes some things have something in common'. The 1 Philosophical Writings of Peirce, ed. Justus Buehler (New York: Dover Publications, 1955), 248. 2 Laurence Goldstein, 'Scientific Scotism – The Emperor's New Trousers or Has Armstrong Made Some Real Strides?', Australasian Journal of Philosophy, vol 61, No. -

Contemporary Perspectives on Natural Law

1 CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVES ON NATURAL LAW 2 [Dedication/series information/blank page] 3 CONTEMPORARY PERSPECTIVES ON NATURAL LAW NATURAL LAW AS A LIMITING CONCEPT 4 [Copyright information supplied by Ashgate] 5 CONTENTS Note on the sources and key to abbreviations and translations Introduction Part One The Concept of Natural Law 1. Ana Marta González. Natural Law as a Limiting Concept. A Reading of Thomas Aquinas Part Two Historical Studies 2. Russell Hittinger. Natural Law and the Human City 3. Juan Cruz. The Formal Foundation of Natural Law in the Golden Age. Vázquez and Suárez’s case 4. Knud Haakonssen. Natural Law without Metaphysics. A Protestant Tradition 5. Jeffrey Edwards. Natural Law and Obligation in Hutcheson and Kant 6. María Jesús Soto–Bruna. Spontaneity and the Law of Nature. Leibniz and the Precritical Kant 7. Alejandro Vigo. Kant’s Conception of Natural Right 8. Montserrat Herrero. The Right of Freedom Regarding Nature in G. W. F. Hegel’s Philosophy of Right 6 Part Three Controversial Issues about Natural Law 9. Alfredo Cruz. Natural Law and Practical Philosophy. The Presence of a Theological Concept in Moral Knowledge 10. Alejandro Llano. First Principles and Practical Philosophy 11. Christopher Martin. The Relativity of Goodness: a Prolegomenon to a Rapprochement between Virtue Ethics and Natural Law Theory 12. Urbano Ferrer. Does the Naturalistic Fallacy Reach Natural Law? 13. Carmelo Vigna. Human Universality and Natural Law Part Four Natural Law and Science 14. Richard Hassing. Difficulties for Natural Law Based on Modern Conceptions of Nature 15. John Deely. Evolution, Semiosis, and Ethics: Rethinking the Context of Natural Law 16. -

Matthew Paris's Chronica Majora and Allegations Of

2018 HAWAII UNIVERSITY INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCES ARTS, HUMANITIES, SOCIAL SCIENCES & EDUCATION JANUARY 3 - 6, 2018 PRINCE WAIKIKI HOTEL, HONOLULU, HAWAII MATTHEW PARIS’S CHRONICA MAJORA AND ALLEGATIONS OF JEWISH RITUAL MURDER MEIER, DAVID DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL SCIENCES DICKINSON STATE UNIVERSITY DICKINSON, NORTH DAKOTA Dr. David Meier Department of Social Sciences Dickinson State University Dickinson, North Dakota Matthew Paris’s Chronica Majora and Allegations of Jewish Ritual Murder Synopsis: Robert Nisbet recognized Matthew Paris as “admittedly one of the greatest historians, if not the greatest in his day.” Matthew provided “the most detailed record of events unparalleled in English medieval history” from 1236-1259. Within the chronicle, allegations of Jewish ritual murder rested alongside classical sources in various languages, including Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Hebrew. Matthew Paris’s Chronica Majora and Allegations of Jewish Ritual Murder David A. Meier, Dickinson State University Allegations of Jewish ritual murder in medieval European chronicles rested alongside classical sources in various languages, including Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Hebrew. Hartmann Schedel’s Weltchronik 1493 (2001) depicted Simon of Trent’s alleged murder by the local Jewish community in 1475 in a manner that mirrored alleged Jewish ritual murders in England in 1144 and 1255.1 Between 1144 and 1493, allegations of Jewish ritual murder spread and flourished. Matthew Paris’s Chronica Majora emerged at historical crossroads where allegations of Jewish ritual murder spread beyond England and into continental Europe. Before the century finished in 1290, England had expelled its Jewish population inspiring many regions on the continent to follow suit in the coming years.2 In offering a written record, chroniclers bridged narrative history from ancient times (largely Biblical) with contemporary culture, history, society, politics and nascent legal systems, employed, in turn, by both church and state in the High Middle Ages. -

Cognitive Issues in the Long Scotist Tradition

Online Conference 11-13 February 2021 Cognitive Issues in the Long Scotist Tradition Thursday 11/2 Cognitive Issues in Early Scotism Chair: Daniel Heider 12:45–13:00 CET Introduction Daniel Heider and Claus A. Andersen 13:00–13:50 CET Giorgio Pini (Fordham University, New York): In God’s Mind: Divine Cognition in Duns Scotus and Some Scotists 14:00–14:50 CET Richard Cross (Notre Dame University): The Ontological Status of esse intelligibile in William of Alnwick Coffee Break 15:10–16:00 CET Francesco Fiorentino (Q. Orazio Flacco High School, Bari): Cognitive Being and the Divine Ideas in the First Two Centuries of Scotism 16:10–17:00 CET Marina Fedeli (University of Macerata): The Species Intelligibilis in the Cognitive Process in Early Scotism, especially in Alnwick Coffee Break 17:20–18:10 CET Damian Park (Boston College): The Non-Beatific Vision of God according to Franciscus de Mayronis (c. 1285–1328) Friday 12/2 Cognitive Issues in Scotism and Reformed Protestant Thought Chair: Ueli Zahnd 11:00–11:50 CET Ueli Zahnd (University of Geneva): The Epistemological Limits of Religious Images: On the Scotist Sources of a Reformed Theological Tenet 12:00–12:50 CET Arthur Huiban (University of Geneva): Melanchthon and the Will: An Early Protestant Reception of Scotist Epistemology? Coffee Break 13:10–13:50 CET Giovanni Gellera (University of Geneva): Univocity of Being, the Cogito and “Proto-Idealism in Johannes Clauberg (16221665) Lunch break Cognitive Issues in Baroque Scotism I Chair: Claus A. Andersen 15:00–15:50 CET Daniel Heider (University