Vol 75 Anglais Final.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theology Papers and Journal Articles School of Theology 2007 Classified timelines of ernacularv liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy Russell Hardiman University of Notre Dame Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article Part of the Religion Commons This article was originally published as: Hardiman, R. (2007). Classified timelines of vernacular liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy. Pastoral Liturgy, 38 (1). This article is posted on ResearchOnline@ND at https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article/9. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Classified Timelines of Vernacular Liturgy: Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy Russell Hardiman Subject area: 220402 Comparative Religious Studies Keywords: Vernacular Liturgy; Pastoral vision of the Second Vatican Council; Roman Policy of a single translation for each language; International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL); Translations of Latin Texts Abstract These timelines focus attention on the use of the vernacular in the Roman Rite, especially developed in the Renewal and Reform of the Second Vatican Council. The extensive timelines have been broken into ten stages, drawing attention to a number of periods and reasons in the history of those eras for the unique experience of vernacular liturgy and the issues connected with it in the Western Catholic Church of our time. The role and function of International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL) over its forty year existence still has a major impact on the way we worship in English. This article deals with the restructuring of ICEL which had been the centre of much controversy in recent years and now operates under different protocols. -

MEV 2013 1-2.Szam

MAGYAR EGYHÁZTÖRTÉNETI VÁ ZLATOK essays in church history in hungary 2013/1–2 MAGYAR EGYHÁZTÖRTÉNETI ENCIKLOPÉDIA MUNKAKÖZÖSSÉG BUDAPEST, 2014 Kiadó – Publisher MAGYAR EGYHÁZTÖRTÉNETI ENCIKLOPÉDIA MUNKAKÖZÖSSÉG (METEM) Pannonhalma–Budapest METEM INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CHURCH HISTORY IN HUNGARY Toronto, Canada HISTORIA ECCLESIASTICA HUNGARICA ALAPÍTVÁNY Szeged www.heh.hu Alapító † Horváth Tibor SJ Főszerkesztő – General Editor CSÓKA GÁSPÁR Szerkesztőbizottság – Board of Editors HUNGARY: Balogh Margit, Barna Gábor, Beke Margit, Csóka Gáspár, Érszegi Géza, Kiss Ulrich, Lakatos Andor, Mészáros István, Mózessy Gergely, Rosdy Pál, Sill Ferenc, Solymosi László, Szabó Ferenc, Török József, Várszegi Asztrik, Zombori István; AUSTRIA: Szabó Csaba; GERMANY: Adriányi Gábor, Tempfli Imre ITALY: Molnár Antal, Németh László Imre, Somorjai Ádám, Tóth Tamás; USA: Steven Béla Várdy Felelős szerkesztő – Editor ZOMBORI ISTVÁN Felelős kiadó – Publisher VÁRSZEGI ASZTRIK Az angol nyelvű összefoglalókat fordította: PUSZTAI-VARGA ILDIKÓ ISSN 0865–5227 Nyomdai előkészítés: SIGILLUM 2000 Bt. Szeged Nyomás és kötés: EFO Nyomda www.efonyomda.hu Tartalom TANULMÁNYOK – essays TAMÁSI Zsolt Püspöki székek betöltése 1848-ban: állami beavatkozás vagy katolikus egyházi autonómia. Értelmezési szempontok a magyar nemzeti zsinati készületek tükrében 5 The filling of Episcopal chairs in 1848: state intervention or Catholic Church autonomia. Posibilities of interpretational in the mirror of national Hungarian synodical preparations. SARNYAI Csaba Máté Szerb–magyar -

National Bulletin Onlitur ~

Number 152 Volume 31 Spring 1998 Confirmation and Initiation national bulletin onLitur ~- Confirmation and Initiation National Bulletin on Liturgy A review published by the - Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops. This bulletin is primarily pastoral in scope. Editor: It is prepared for members of parish liturgy Zita E. Maier. OSU committees, readers, musicians, singers. Editorial Office: catechists, teachers. religious, seminarians. NATIONAL LITURGY OFFICE clergy, diocesan liturgical commissions. 90 Parent Avenue (613) 241-9461 and for all who are involved in preparing, Ottawa, Ontario extension 276 celebrating, and improving the community's K1N 7B1 life of worship and prayer. Web Site: http://www.cccb.ca E-mail: [email protected] Editorial commentary in the bulletin is the Business Office: responsibility of the editor. NOVALIS P.O. Box 990 Outremont, Quebec H2V 4S7 1-800-NOVALIS (668-2547) Subscriptions The price of a single issue is now $5.50. For one year, excluding 7% GST: Individual copies and back issues must be 1-4 copies: purchased from the publisher. Customers Canada $17 should add to the price the GST (7%) after United States $20 us adding one of the following amounts for Other countries $27 us shipping and handling: Five or more copies: For orders of Canada $15 $99.99 and less: 8% ($2.00 minimum United States $18 US charge) Other countries $25 US $1 00.00 to $999.99: 5% $1 ,000.00 and more: shipping costs only Quantity discount for this issue: National Bulletin on Liturgy is published by For 50 or more copies to one address, Publications SeNice of the CCCB and 30% discount. -

ADESJO Joins Friends in Canada March-April 2013 $1.00 to Celebrate Its 50 Years of Community Development in San José De Ocoa, Dominican Republic Story on Page 12

th anniver 50 sary ADESJO joins friends in Canada March-April 2013 $1.00 to celebrate its 50 years of community development in San José de Ocoa, Dominican Republic Story on page 12 March-April 2013/Scarboro Missions 1 EDITORIAL Dear friend of Scarboro Missions... Thank you for your faithful prayers and generosity to us. Whom shall I send? We will continue to be good stewards of all your gifts as we put ourselves at the service of By Kathy Gillis others. Please note our dona- CONTENTS tion envelope inside this issue he writers in this issue are pas- ence, and innate worth of all creatures. ment based on solidarity and the belief for your convenience. FEATURES sionate about justice—justice They write: “All creatures, humans in God’s desire that “they may have life for the poor and justice for the and otherwise, were ‘made from the and have it to the full” (John 10:10). Justice in the World T We welcome enquiries about Scarboro’s Earth. In the first article, Fr. Bill Ryan, soil,’ i.e. they are flesh. In Christ, May you respond like the high By Bill Ryan, S.J. 4 priest and lay missioner programs. special advisor to the Jesuit Forum for God entered into unity, not only with school students in the D.R.E.A.M.S. Please contact: Politics and religion Social Faith and Justice in Toronto, human beings, but also with the entire feature who did service volunteering in Fr. Ron MacDonell (priesthood): By Bishop Benedict Singh 8 writes about Justice in the World, a visible and material world. -

Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos , Coloquios | 2008 Canadian English-Speaking Catholics, Latin America and the Refugee Issue Unde

Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos Nouveaux mondes mondes nouveaux - Novo Mundo Mundos Novos - New world New worlds 2008 Coloquios | 2016 Canadian English-speaking Catholics, Latin America and the Refugee issue under Trudeau Daniela Saresella Publisher Mondes Américains Electronic version URL: http://nuevomundo.revues.org/69612 Brought to you by École des hautes études ISSN: 1626-0252 en sciences sociales Electronic reference Daniela Saresella, « Canadian English-speaking Catholics, Latin America and the Refugee issue under Trudeau », Nuevo Mundo Mundos Nuevos [Online], Workshops, Online since 10 October 2016, connection on 19 December 2016. URL : http://nuevomundo.revues.org/69612 This text was automatically generated on 19 décembre 2016. Nuevo mundo mundos nuevos est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Canadian English-speaking Catholics, Latin America and the Refugee issue unde... 1 Canadian English-speaking Catholics, Latin America and the Refugee issue under Trudeau Daniela Saresella 1 Historically, English-speaking Catholics who arrived from Ireland and settled in Protestant-dominated societies were a small minority. During the twentieth century, Toronto saw the arrival of many immigrants mostly from Italy, Ukraine and other Catholic countries. Since they did not have much social and political weight, English- speaking Catholics organized a network of institutions in the fields of education, health and welfare to support their community. English-speaking Catholics gained recognition in 1945, when James McGuigan, archbishop of Toronto, became the first prelate outside Québec to receive the cardinal’s hat.1 2 After WWII a period of revitalization was inaugurated : the return to peace brought renewed optimism as ordinary Canadians looked forward to leading normal lives. -

The Denv DENVER, COLO., WEDNESDAY, JULY 12, 1978

The Denv DENVER, COLO., WEDNESDAY, JULY 12, 1978 !M ‘Christ-Clowns' Help Us to Celebrate Life (Photo by Mark Kirvluk) “ A circus celebrates life . gives one that sunset on a hope-full note,” says a newsletter of St. joined teachers and other students in dressing as clowns enthusiasm which keeps the routineness of sunrise and Mary’s School of Religion in Littleton. These fifth graders • I lor the final day of the summer session. Story page 7. Abortion Still Hot Issue •i For Political Candidates Ry Teresa Coyle states and several foreign countries took part. VATICAN CITY (NC) — Shortly before beginning y ST. LOUIS (NC) — Politicians who found abortion a hot Besides seeking to step up the political activities of its his summer working vacation at Castelgandolfo, Pope political issue in the past will find it getting even hotter if 11 million members, the organization reaffirmed its Paul urged vacationers to use their time off as a the National Right to Life Committee succeeds with plans policy against violent anti-abortion activities, drew chance to enjoy and meditate on the world around f made at its recent convention in St. Louis. numerous parallels between the pro-life movement and them. ; "Those men and women who do not understand the life the civil rights movement, and endorsed non-violent He told thousands in St. Peter’s Square to have a issues and will not vote to protect the right to life will find direct actions such as abortion clinic sit-ins. good vacation, but then added a word of advice: “ Seek it very, very difficult to be elected to office.” said Dr. -

Canadian Participation in Episcopal Synods, 1967-1985

CCHA, Historical Studies, 54 (1987), 145-157 Canadian Participation in Episcopal Synods, 1967-1985 by Michael W. HIGGINS and Douglas R. LETSON University of St. Jerome’s College, Waterloo, Ontario On the tenth of February, 1986, Bernard Hubert, President of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops (CCCB), released a twelve-page summary report of the Canadian delegation’s role at the Extraordinary Synod convened in Rome by John Paul II late in 1985. The penultimate paragraph of that statement articulates our sentiments as media observers at that Synod; it also confirms the assessment of Council father and frequent synod delegate Gerald Emmett Carter,1 as well as echoing the expressed accolades of the majority of the non-U.S. delegates with whom we became acquainted during the 1985 Extraordinary Synod. Hubert concludes: Until now, the Canadian delegates to various Synods honoured the CCCB because they clearly expressed the Canadian experience on the subject presented. They were not afraid to bring to light the questions, remarks and suggestions from the Christian communities at home. They did so with confidence and openness. They were ready to accept criticisms and decisions formulated by the whole Synod to which they participated. I believe we have reason to be proud of the contribution of the Canadian delegates to past Synods. In its delegates, the CCCB provides the universal Church with a rich and loyal contribution for the benefit of all.2 In this paper we have accepted Hubert’s implicit invitation to examine the historical breadth mentioned in his observation, to weigh his thesis of the Canadian delegatio’'s historical tradition of forthrightness in relating the Canadian experience, and we intend also to test the thesis that Canadian delegates have made a “rich and loyal contribution.” To appreciate the role the Canadians have played, one must first recall the tenor of the documents from which the synod takes its origin. -

Remembering Mcluhan New Exhibit Shines Spotlight on Visionary Educator St.Michael’S Contents the University of St

Volume 55 Number 2 Fall 2016 stmikes.utoronto.ca St.University of St. Michael’s Michael’s College in the University of Toronto Alumni Magazine REMEMBERING McLUHAN New Exhibit Shines Spotlight on Visionary Educator St.Michael’s Contents The University of St. Michael’s College Alumni Magazine 12 12 An affair to remember PUBLISHER & EDITOR There may be 70 wineries in the Niagara Leslie Belzak Region, but there is only one Foreign Affair Director of Alumni Affairs, University of St. Michael’s College By Christine Arthurs 0T0 MANAGING EDITOR 16 The world’s his stage Ruth Hanley From Toronto to Broadway, and beyond, with St. Mike’s grad RJ Hatanaka COPY EDITORS By Hilary Coles 1T0 Laurel-Ann Finn, Christine Henry 9T6, Betty Noakes 1T3 19 Remembering McLuhan CAMPUS NOTES New exhibit shines spotlight on Betty Noakes 1T3 16 visionary educator By Katherine Ing, Michael CONTRIBUTORS McLuhan, Kalina Nedelcheva Christine Arthurs 0T0 and Simon Patrick Rogers Hilary Coles 1T0 Kathryn Elton Katherine Ing 25 Campus Notes Michael McLuhan David Mulroney 7T8 Bulletin Board Kalina Nedelcheva 30 Duane Rendle Simon Patrick Rogers 33 Honours Emily VanBerkum1T2 Distribution Columns Office of University Advancement 03 FROM FOUNDERS HOUSE Art DIRECTION & DESIGN 19 A tale of two installations Fresh Art & Design Inc. 04 FIRST FLIGHT COVER St. Basil’s Parish: 160 years of purpose Photography: Michael McLuhan Painting: Pied Pipers All by René Cera 07 KELLY CAFÉ A cup of joe with Nicole LeBlanc Publication Mail Agreement No: 40068944 08 ALUMNI ASSOCIATION A new era of fundraising at USMC Please send comments, corrections and enquiries to the Office of University Advancement 09 IN PRINT University of St. -

Oi1holicregism;

Rally Scheduled Sept. 26 ^ ( Educators Convene on Social Justice By Register Reporter education to the problems of World Peace Committee of the He is currently working on a The response of education to modern society will be included in United States Catholic Conference doctoral dissertation toward a social change in the world will be the program, which will end with in Washington, D.C. Ph.D. in philosophy from Harvard studied by Metro Denver a Liturgy celebrated by He is also a visiting lecturer Divinity School. His field of educators at two special forums Monsignor William Jones, Vicar in ethics at St. John’s Seminary in specialization is ethics and on Sept. 26 sponsored Central for Education. Brighton, Massachusetts. international politics. Area School Services. On the evening of Sept. 26, A priest of the Boston Father Hehir recently Both meetings will feature Archbishop James V, Casey will archdiocese, Father Hehir was published the article ’ ’The Church Father Bryon Hehir. nationally host an “ Educators’ Rally” to be ordained in 1966. He attended in the Population Year: Notes on a recognized authority on social held at Christ the King parish Kings College. Pennsylvania and Strategy” in the April 1974 issue of justice and the Church. auditorium beginning at 8 p.m. St. John’s Seminary, Brighton. Theological Studies. Principals will gather on the 3 g morning of Sept. 26 to hear a Father Hehir will speak on the series of three talks by Father overall impact of social justice on Hehir centering on “ Education in education. A reception and 1HE turn Today’s World” informal discussion time will Bishop George Evans will follow the talk. -

SEASON He Used to Be, He Is Now Sur the Public Is Invited to the Passed in Many Areas, the Bish Program Beginning at 7:30 P.M

Ordain Wonjen? Bishops Urge Passage Qdl. Mahif f Urges Discussion Of Amendment One Albany ~ The State's Catho quate employment opportuni -\ Vatican City — dRNS) — Canadian prelate declared here lic Bishops have unanimously ties; health, mental health and that historical! arguments urged voter adoption of the new environmental health; child against the ordination of woqi- Community Development article care and aged care; transporta en as priests can. no longer be whicfar appears on tme November tion and communications; civil, cultural, recreational and other considered valid and urged the ballot as Amendment Number community facilities and ser Pope to establish a [special One. vices; or * any combination of mission to consider *wheth' A yes vote on Community De such $urposes.'* women should' be Ordained. velopment* they say, will bring Cardinal George Flahiff better living conditions for Presently the JUw does not If Rose Kennedy, the devout distance to appreciate it." Winnipeg told delegates to ' families, the aged,, children in allow the government and pri daily Communicant, was bewil Okay. Synod of Bishops that so far both city and suburbs. vate enterprise to cooperate ef dered by Leonard J'Bernstein's he knew "there are no fectively in promoting such concept of the Roman .Catholic Am leaving today for An tic objections" to reconsider The amendment would re programs. Mass she covered hej true emo chorage. the whole question\ He said place the Housing Section of tions with customary courage. • • • spoke for the Canadian Bishop's' the Constitution which - was It provides only that munici It was "fine," she told radiant The funeral service for Ben Conference. -

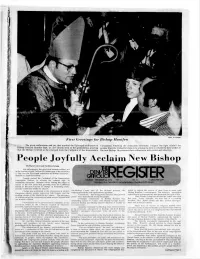

OI1HCXICREGISTER Conception

tu-1 l Photo by Joseph's First Greetings for Bishop Hanifen The great enthusiasm and joy that marked the Episcopal ordination of Conception following the ordination ceremony. Despite the light rainfall the Bishop Richard Hanifen Sept. 21, are clearly seen in the spontaneous greeting people lined the Cathedral steps to be among the first to extend the best wishes to that the Bishop received as he emerged from the Cathedral of the Immaculate the new Bishop. He returned their enthusiasm with smiles and affection. N People Joyfully Acclaim New Bishop By Mary Lynett and Cathleen Grupp Age-old pagentry flavored with Spanish culture, set in the context of post Vatican II Catholicism in the seventies — this was the Episcopal ordination of Bishop Richard C. DENk?l Hanifen as Auxiliary Bishop. Crowds packed the Cathedral of the Immaculate OI1HCXICREGISTER Conception. Denver, to witness the colorful Sept. 20 THUteD# V, SEPTEMBER 26, 1974 VOl. 1. NO, 10 15 CENTS PER COPY ordination ceremony. Autumn colors tinting the edges of SERVING THE CATHOLICS OF NORTHERN COLORADO 72 YEARS leaves of the few trees still growing near the Cathedral hinted at the post-Vatican II change in leadership style, joyfully celebrated inside the church. Change was evidenced in the alternation of ancient Archbishop Casey and all the bishops present, the asked to return the service of their lives in union with Gregorian chants, gentle American folk hymns, and the congregation broke into spontaneous applause. Bishop Hanifen's committment. The offertory procession striking chords of the Mariachi de Colores, The ministers Carnations, "that bring peace because they grew in symbolically represented all who bestowed their gift of life. -

Spiritual Leaders in the IFOR Peace Movement Part 1

A Lexicon of Spiritual Leaders In the IFOR Peace Movement Part 1 Version 3 Page 1 of 52 2010 Dave D’Albert Argentina ............................................................................................................................................. 3 Adolfo Pérez Esquivel 1931- .......................................................................................................... 3 Australia/New Zealand ........................................................................................................................ 4 E. P. Blamires 1878-1967 ............................................................................................................... 4 Austria ................................................................................................................................................. 5 Kaspar Mayr 1891-1963 .................................................................................................................. 5 Hildegard Goss-Mayr 1930- ............................................................................................................ 6 Belgium ............................................................................................................................................... 8 Jean van Lierde ............................................................................................................................... 8 Czech .................................................................................................................................................