Canadian Participation in Episcopal Synods, 1967-1985

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy

The University of Notre Dame Australia ResearchOnline@ND Theology Papers and Journal Articles School of Theology 2007 Classified timelines of ernacularv liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy Russell Hardiman University of Notre Dame Australia, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article Part of the Religion Commons This article was originally published as: Hardiman, R. (2007). Classified timelines of vernacular liturgy: Responsibility timelines & vernacular liturgy. Pastoral Liturgy, 38 (1). This article is posted on ResearchOnline@ND at https://researchonline.nd.edu.au/theo_article/9. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Classified Timelines of Vernacular Liturgy: Responsibility Timelines & Vernacular Liturgy Russell Hardiman Subject area: 220402 Comparative Religious Studies Keywords: Vernacular Liturgy; Pastoral vision of the Second Vatican Council; Roman Policy of a single translation for each language; International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL); Translations of Latin Texts Abstract These timelines focus attention on the use of the vernacular in the Roman Rite, especially developed in the Renewal and Reform of the Second Vatican Council. The extensive timelines have been broken into ten stages, drawing attention to a number of periods and reasons in the history of those eras for the unique experience of vernacular liturgy and the issues connected with it in the Western Catholic Church of our time. The role and function of International Committee of English in the Liturgy (ICEL) over its forty year existence still has a major impact on the way we worship in English. This article deals with the restructuring of ICEL which had been the centre of much controversy in recent years and now operates under different protocols. -

MEV 2013 1-2.Szam

MAGYAR EGYHÁZTÖRTÉNETI VÁ ZLATOK essays in church history in hungary 2013/1–2 MAGYAR EGYHÁZTÖRTÉNETI ENCIKLOPÉDIA MUNKAKÖZÖSSÉG BUDAPEST, 2014 Kiadó – Publisher MAGYAR EGYHÁZTÖRTÉNETI ENCIKLOPÉDIA MUNKAKÖZÖSSÉG (METEM) Pannonhalma–Budapest METEM INTERNATIONAL SOCIETY FOR ENCYCLOPEDIA OF CHURCH HISTORY IN HUNGARY Toronto, Canada HISTORIA ECCLESIASTICA HUNGARICA ALAPÍTVÁNY Szeged www.heh.hu Alapító † Horváth Tibor SJ Főszerkesztő – General Editor CSÓKA GÁSPÁR Szerkesztőbizottság – Board of Editors HUNGARY: Balogh Margit, Barna Gábor, Beke Margit, Csóka Gáspár, Érszegi Géza, Kiss Ulrich, Lakatos Andor, Mészáros István, Mózessy Gergely, Rosdy Pál, Sill Ferenc, Solymosi László, Szabó Ferenc, Török József, Várszegi Asztrik, Zombori István; AUSTRIA: Szabó Csaba; GERMANY: Adriányi Gábor, Tempfli Imre ITALY: Molnár Antal, Németh László Imre, Somorjai Ádám, Tóth Tamás; USA: Steven Béla Várdy Felelős szerkesztő – Editor ZOMBORI ISTVÁN Felelős kiadó – Publisher VÁRSZEGI ASZTRIK Az angol nyelvű összefoglalókat fordította: PUSZTAI-VARGA ILDIKÓ ISSN 0865–5227 Nyomdai előkészítés: SIGILLUM 2000 Bt. Szeged Nyomás és kötés: EFO Nyomda www.efonyomda.hu Tartalom TANULMÁNYOK – essays TAMÁSI Zsolt Püspöki székek betöltése 1848-ban: állami beavatkozás vagy katolikus egyházi autonómia. Értelmezési szempontok a magyar nemzeti zsinati készületek tükrében 5 The filling of Episcopal chairs in 1848: state intervention or Catholic Church autonomia. Posibilities of interpretational in the mirror of national Hungarian synodical preparations. SARNYAI Csaba Máté Szerb–magyar -

JANE DOE NO. 28 Plaintiff - and

-:« Court File No. ONTARIO SUPERIOR COURT OF JUSTICE BETWEEN: JANE DOE NO. 28 Plaintiff - and - THE ESTATE OF CHARLES H. SYLVESTRE, TH!= ROMAN CATHOLIC EPISCOPAL CORPORATION OF THE DIOCESE OF LONDON IN ONTARIO, The Estate of John Christopher Cody, The Estate of GERALD EMMETI CARTER, JOHN MICHAEL SHERLOCK, S1. CLAIR CATHOLIC DISTRICT SCHOOL BOARD, THE SARNIA POLICE FORCE, JOHN SMITH, J. TORRANCE, LE CONSEIL SCOLAIRE DE DiSTRICT DES ECOLES CATHOUQUES DU SUD-OUEST, and THE SISTERS OF CHARITY OF OTIAWA (also known as GREY NUNS OF THE CROSS "SOEURS GRISES DE LA CROIX") Defendants STATEMENT OF CLAIM TO THE DEFENDANT(S) A LEGAL PROCEEDING HAS BEEN COMMENCED AGAINST YOU by the plaintiff(s). The claim made against you appears on the following pages. IF YOU WISH TO DEFEND THIS PROCEEDING, you or an Ontario lawyer acting for you must prepare a statement of Defence in Form 18A prescribed by the Rules of Civil Procedure, serve it on the plaintiff(s) lawyer(s) or, where the plaintiff(s) do(es) not have a lawyer, serve it on the plaintiff(s), and file it, with proof of service, in this court office, WITHIN TWENTY DAYS after this statement of claim is served on you, if you are served in Ontario. If you are served in another province or territory of Canada or in the United States of America, the period for serving and filing your statement of defence is forty days. If you are served outside Canada and the United States of America, the period is sixty days. Instead of serving and filing a statement of defence, you may serve and file a notice of intent to defend in Form 18B prescribed by the Rules of Civil Procedure. -

The Denver Catholic Register WEDNESDAY JUNE 20, 1979 VOL

The Denver Catholic Register WEDNESDAY JUNE 20, 1979 VOL. LIV NO. 36 Colorado’s Largest Weekly 32 PAGES 25 CENTS PER COPY Conrad, an Editorial Cartoonist Whose Pen Has a Tongue of Fire By Thomas M. Jenkins Assaulting complacency, ridiculing corruption and lambasting the pretentions, malfeasances and idiotic decisions of modern bureaucratic government as well as the personal and spiritual plight of the American citizen, Paul Conrad is a cartoonist who dares to be controversial and take an unequivocal stand. In the process, his six cartoons a week for the Los Angeles Times have been raising blood pressures for the past 16 years. After two Pulitzer Prizes and two published books, his caustic im agery continues to be syndicated in 150 newspapers. Conrad, who was with the Denver Post for 13 years as an editorial cartoonist, has justly earned his place in the procession of the illustrious cartoonist pens of Daumier, Nast, Levine, MacNelly, Mauldin, Herblock, Wright and Oliphant. He maintains the gutsy tradition of those satirists whose ridicule contains the truth necessary to puncture the bubbles of inept leadership, overuse of power, the inability to act, the mistreatment of the disadvantaged, elderly and ignorant, the prolongation of war and the continuation of a destructive monetary policy. If he seems cruel to the politician, it is only to be kind to the Republic. Religious Conviction Unique in presentation is Conrad’s religious conviction. Under no constraining directives from the Los Angeles Times, Conrad is always forthright and sometimes brutal in confronting the spiritual issues of the day. In that process, he disturbs (and even angers) many of his readers as he forces them to look at themselves and their patterns of living. -

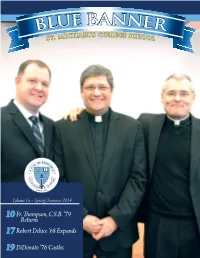

2014 Spring/Summer

bbllue banner HAEL’S COLLEGE SC ST. MIC HOOL Volume 16 ~ Spring/Summer 2014 10 Fr. ompson, C.S.B. ’79 Returns 17 Robert Deluce ’68 Expands 19 DiDonato ’76 Castles lettersbb tol theu editore banner HAEL’S COLLEGE S ST. MIC CHOOL The St. Michael’s College School alumni magazine, Blue Banner, is published two times per year. It reflects the history, accomplishments and stories of graduates and its purpose is to promote collegiality, respect and Christian values under the direction of the Basilian Fathers. PRESIDENT: Terence M. Sheridan ’89 CONTACT DIRECTORY EDITOR: Gavin Davidson ’93 St. Michael’s College School: www.stmichaelscollegeschool.com CO-EDITOR: Michael De Pellegrin ’94 Blue Banner Online: www.mybluebanner.com CONTRIBUTING EDITORS Basilian Fathers: www.basilian.org Kimberley Bailey, Michael Flood ’87, Jillian Kaster, Pat CISAA (Varsity Athletic Schedule): www.cisaa.ca Mancuso ’90, Harold Moffat ’52, Marc Montemurro ’93, Twitter: www.twitter.com/smcs1852 Joe Younder ’56, Stephanie Nicholls, Terence Sheridan Advancement Office: [email protected] ’89. Alumni Affairs: [email protected] TABLE OF CONTENTS Archives Office: [email protected] Blue Banner Feedback: [email protected] School Administration Message 4 Communications Office: [email protected] Alumni Association Message 5 Tel: 416-653-3180 ext. 292 Editor’s Letter 6 Fax: 416-653-8789 Letters to the Editor 7 E-mail: [email protected] Around St. Mike’s 8 • Admissions (ext. 195) Fr. Thompson, C.S.B. ’79 10 • Advancement (ext. 118) Returns Home as New President • Alumni Affairs (ext. 273) Securing Our Future by Giving Back: 12 Michael Flood ’87 • Archives (ext. -

Diocese of London Series (F01-S128)

Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada Finding Aid - Diocese of London series (F01-S128) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.5.4 Printed: August 10, 2020 Language of description: English Congregation of the Sisters of St. Joseph in Canada 485 Windermere Road P.O. Box 487 London Ontario Canada N6A 4X3 Telephone: 519-432-3781 ext. 404 Fax: 519- 432-8557 Email: [email protected] https://www.csjcanada.org/ http://www.archeion.ca/index.php/diocese-of-london-series Diocese of London series Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 4 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Access points ................................................................................................................................................... 5 Collection holdings .......................................................................................................................................... 5 F01-S128--01, Bishop Fallon (1910-1953) ................................................................................................. -

Proquest Dissertations

NOTE TO USERS This reproduction is the best copy available. UMI® Unveiling the Army of Mary: A Gendered Analysis of a Conservative Catholic Marian Devotional Organization Paul Gareau A Thesis In the Department of Religion Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts (History & Philosophy of Religion) at Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada September 2009 © Paul Gareau, 2009 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre rif&rence ISBN: 978-0-494-63174-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-63174-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

A Tribute to Gregory Baum Michael W

Sacred Heart University DigitalCommons@SHU Mission and Catholic Identity Publications Office of Mission and Catholic Identity 12-2-2011 The ourJ nalist as Theologian: A Tribute to Gregory Baum Michael W. Higgins Sacred Heart University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/mission_pub Part of the Catholic Studies Commons, and the Religious Thought, Theology and Philosophy of Religion Commons Recommended Citation Higgins, Michael W. "The ourJ nalist As Theologian." Commonweal 138.21 (2011): 12-18. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Office of Mission and Catholic Identity at DigitalCommons@SHU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Mission and Catholic Identity Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@SHU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ARTICLE The Journalist as Theologian A Tribute to Gregory Baum Michael W. Higgins heir number is not legion, and it continues to not as a theological shaper or foundational thinker, but as dwindle. The few remaining Second Vatican a journalist following his curiosity wherever it leads him. Council Fathers alive today are in their nineties, To Baum, one should note, “journalist” does not betoken and their able theological experts—the periti— a scribbler with a deadline, but rather someone inexhaust- notT far behind. But at least one in this august company is ibly fascinated with ideas, intellectual trends, and currents. not going quietly into the good night of retirement: Grego- His career has balanced the Good News with news in pi- ry Baum, mathematician, theologian, ex-Augustinian friar, oneering proportions. -

Le “AFIN D'être EN PLEINE POSSESSION DE SES MOYENS”

$6.00 US Le“AFIN D’ÊTREFORUM EN PLEINE POSSESSION DE SES MOYENS” VOLUME 34, #4 SPRING/PRINTEMPS- 2010 “Photo by Annette Paradis King” New Website: francoamericanarchives.org another pertinent website to check out - Franco-American Women’s Institute: http://www.fawi.net Le Forum This issue of Le Forum is dedicated in loving memory to Irène Simoneau. Le Centre Franco-Américain Ce numéro du “Forum” est dédié à la Université du Maine Orono, Maine 04469-5719 douce mémoire de Irène Simoneau, voir page 3... [email protected] Téléphone: 207-581-FROG (3764) Sommaire/Contents Télécopieur: 207-581-1455 Volume 34, Numéro 4 FALL/AUTOMNE Features Éditeur/Publisher Yvon A. Labbé Letters/Lettres...............................................................................9, 19-20 L’État du Maine....................................................................................8, 9 Rédactrice/Gérante/Managing Editor Lisa Desjardins Michaud L’État du Connecticut.......................................................................10-18 L’État du Massachusetts.........................................................................23 Mise en page/Layout Lisa Desjardins Michaud L’État du Minnesota.......................................................37, 38, 42, 47, 48 Books/Livres.................................................................................20, 36-38 Composition/Typesetting Robin Ouellette Music/Musique..................................................................................39-42 Lisa Michaud Artist/Artiste......................................................................................43-44 -

In This Issue New President at U of T Jean Vanier Recruitment at St Mike’S Double Blue

DoubleBlue University of St. Michael’s College Alumni Newsletter Vol. 38, Number 1, Spring 2000 In This Issue New President at U of T Jean Vanier Recruitment at St Mike’s Double Blue A Letter from the Editor What a startling image the cover of the The University of Alumni Affairs is looking forward to the St. Michael’s second issue of the DOUBLE BLUE, the visit of Jean Vanier to St. Michael’s on College Alumni Newsletter University of St. Michael’s College 27 October, 2000. He will not only Published twice a year by: Alumni Newsletter, portrays! A deliver the Kelly Lecture at Convocation The Alumni Association dramatic rendition of St. Michael the Hall that evening but will also hold a 81 St. Mary Street Archangel, created by Anne Tully, special workshop during the day Toronto, Canada M5S 1J4 gently reaches out to those journeying primarily for theological students at the Editor: Mary Ellen Burns through the winter landscape of the St. Toronto School of Theology and for a Production: Michael’s Quadrangle. group from the Christianity and Culture Fr. Richard Donovan, CSB Barrett J. Healy programme at the college. Fr. Robert Madden, CSB I am excited about the progress of the Fr. John Madden, CSB newsletter project. After much work In addition to our alumni and friends, Eva Wong and dedication, the Communications this newsletter will be sent, for the first Editorial Commitee Committee of the Alumni Board Duane Rendle time, to all students registered at St. Marie Daly Cook recommended to the editor and a Michael’s College. -

“A Dicastery for the Laity: Past and Future ...”

Cardinal Stanisław Ryłko President Pontifical Council for the Laity Vatican City 28TH PLENARY ASSEMBLY OF THE PONTIFICAL COUNCIL FOR THE LAITY “A dicastery for the laity: past and future ...” Rome, 16-18 June 2016 WELCOME ADDRESS TO THE HOLY FATHER Holy Father, The members and consultors of the Pontifical Council for the Laity, who have come together here in Rome for the 28th Plenary Assembly of the dicastery, wish to express their heartfelt gratitude for the gift of this audience and to convey their affection and filial devotion. Our Plenary Assembly has a special characteristic this time because it is bringing to a close a long and fruitful stage in the history of this dicastery. As part of the reform of the Roman Curia, being led by you Holy Father, on 1 September next, the Council will cease to exist as it is presently structured to make way for a new dicastery with extended jurisdiction. In addition to laity, it will also include family and life. The theme guiding the discussions at this Assembly is the following: “A dicastery for the laity: past and future ...”. We wanted to look back over the history of this Council - not without deep emotion - and to thank the Lord for the fifty years of service given to the great cause of the laity in the Church. This dicastery was established by the explicit will of the Vatican Council Fathers, and it has witnessed the abundant fruits that the Second Vatican Council teaching on the laity has generated in the lives of huge numbers of men and women, adults and young people of our time. -

Proquest Dissertations

/YîO-Cfcf LA CONSÉCRATION DES VIERGES IMPLICATIONS JURIDIQUES par Marie-Paul DION Thèse présentée à la Faculté de Droit canonique de l'Université Saint-Paul Ottawa, pour l'obtention du doctorat en droit canonique Ottawa, Canada, 1983 Marie-Paul Dion, Ottawa, Canada, 1983. UMI Number: DC53614 INFORMATION TO USERS The quality of this reproduction is dépendent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleed-through, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complète manuscript and there are missing pages, thèse will be noted. AIso, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI® UMI Microform DC53614 Copyright 2011 by ProQuest LLC AH rights reserved. This microform édition is protected against unauthorized copying underTitle 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 AnnArbor, Ml 48106-1346 En hommage filial au Cardinal Maurice ROY REMERCIEMENTS Nous tenons à remercier cordialement le Père Francis Morrisey, O.M.I., doyen de la Faculté de Droit canonique à l'Université Saint-Paul et le Père Jean Moncion, O.M.I., professeur à cette même Faculté, d'avoir bien voulu accepter la co-responsabilité de la supervision de notre travail. Notre gratitude va aussi à tous nos professeurs, particulièrement au Père Louis-Philippe Vézina, O.M.I., avec qui nous avons souvent discuté de notre projet. Quant au Père Léo Laberge, O.M.I., professeur à la Faculté de Théologie de l'Université Saint-Paul, son érudition et sa disponibilité en firent pour nous un conseiller précieux.