Scanned Image

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Entrevistas Con Veinte Escritores Mexicanos Nacidos En Los 70: De Abenshushan a Xoconostle

Entrevistas con veinte escritores mexicanos nacidos en los 70: De Abenshushan a Xoconostle 0a. inicio.indd 3 7/9/12 3:38:56 PM 0a. inicio.indd 4 7/9/12 3:38:56 PM Entrevistas con veinte escritores mexicanos nacidos en los 70: De Abenshushan a Xoconostle EMILY HIND Logo Universidad de Wayoming 0a. inicio.indd 5 7/9/12 3:38:57 PM Colección Diseño y producción editorial: Ediciones Eón ISBN EÓN: Primera edición: 2012 © Ediciones y Gráficos Eón, S.A. de C.V. Av. México-Coyoacán No. 421 Col. Xoco, Deleg. Benito Juárez México, D.F., C.P. 03330 Tels.: 5604-1204 / 5688-9112 [email protected] Impreso y hecho en México Printed and made in Mexico 0a. inicio.indd 6 7/9/12 3:38:57 PM ÍNDICE Prólogo 11 Vivian Abenshushan 21 Orfa Alarcón 57 Vicente Alfonso 79 Liliana V. Blum 99 Luis Jorge Boone 121 Karen Chacek 143 Alberto Chimal 167 Bernardo Esquinca 205 Bernardo Fernández (Bef) 227 Iris García Cuevas 251 David Miklos 273 0a. inicio.indd 7 7/9/12 3:38:57 PM Ernesto Murguía 297 Guadalupe Nettel 321 Antonio Ortuño 345 Cristina Rascón Castro 355 Ximena Sánchez Echenique 373 Felipe Soto Viterbo 397 Socorro Venegas 429 Nadia Villafuerte 453 Ruy Xoconostle 477 0a. inicio.indd 8 7/9/12 3:38:57 PM AGRADEZCO A Pepe ROJO POR IMPULSAR este proyecto en su inicio al ponerme en contacto con Bef. Admiro mucho Punto cero (1972, Tijuana), la excelente novela que Rojo escribió. Doy las gracias a Alejandra Silva Lomelí y Rubén Leyva por su entusiasmo respecto a la posibilidad de publicar el proyecto, y agradezco la rapidez con que me contestó Cristina Rivera Garza cuando primero busqué una editorial. -

Frontier Re-Imagined: the Mythic West in the Twentieth Century

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2018 Frontier Re-Imagined: The yM thic West In The Twentieth Century Michael Craig Gibbs University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Gibbs, M.(2018). Frontier Re-Imagined: The Mythic West In The Twentieth Century. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5009 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. FRONTIER RE-IMAGINED : THE MYTHIC WEST IN THE TWENTIETH CENTURY by Michael Craig Gibbs Bachelor of Arts University of South Carolina-Aiken, 1998 Master of Arts Winthrop University, 2003 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2018 Accepted by: David Cowart, Major Professor Brian Glavey, Committee Member Tara Powell, Committee Member Bradford Collins, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Michael Craig Gibbs All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION To my mother, Lisa Waller: thank you for believing in me. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I wish to thank the following people. Without their support, I would not have completed this project. Professor Emeritus David Cowart served as my dissertation director for the last four years. He graciously agreed to continue working with me even after his retirement. -

El Llegat Dels Germans Grimm En El Segle Xxi: Del Paper a La Pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira I Virgili [email protected]

El llegat dels germans Grimm en el segle xxi: del paper a la pantalla Emili Samper Prunera Universitat Rovira i Virgili [email protected] Resum Les rondalles que els germans Grimm van recollir als Kinder- und Hausmärchen han traspassat la frontera del paper amb nombroses adaptacions literàries, cinema- togràfiques o televisives. La pel·lícula The brothers Grimm (2005), de Terry Gilli- am, i la primera temporada de la sèrie Grimm (2011-2012), de la cadena NBC, són dos mostres recents d’obres audiovisuals que han agafat les rondalles dels Grimm com a base per elaborar la seva ficció. En aquest article s’analitza el tractament de les rondalles que apareixen en totes dues obres (tenint en compte un precedent de 1962, The wonderful world of the Brothers Grimm), així com el rol que adopten els mateixos germans Grimm, que passen de creadors a convertir-se ells mateixos en personatges de ficció. Es recorre, d’aquesta manera, el camí invers al que han realitzat els responsables d’aquestes adaptacions: de la pantalla (gran o petita) es torna al paper, mostrant quines són les rondalles dels Grimm que s’han adaptat i de quina manera s’ha dut a terme aquesta adaptació. Paraules clau Grimm, Kinder- und Hausmärchen, The brothers Grimm, Terry Gilliam, rondalla Summary The tales that the Grimm brothers collected in their Kinder- und Hausmärchen have gone beyond the confines of paper with numerous literary, cinematographic and TV adaptations. The film The Brothers Grimm (2005), by Terry Gilliam, and the first season of the series Grimm (2011–2012), produced by the NBC network, are two recent examples of audiovisual productions that have taken the Grimm brothers’ tales as a base on which to create their fiction. -

Milena Rodríguez Gutiérrez Poetas Hispanoamericanas Contemporáneas Mimesis

Milena Rodríguez Gutiérrez Poetas hispanoamericanas contemporáneas Mimesis Romanische Literaturen der Welt Herausgegeben von Ottmar Ette Band 91 Poetas hispanoamericanas contemporáneas Poéticas y metapoéticas (siglos XX–XXI) Editado por Milena Rodríguez Gutiérrez Este libro se enmarca dentro del Proyecto de investigación FEM2016-78148P «Las poetas hispanoamericanas: identidades, feminismos, poéticas (Siglos XIX-XXI)», financiado por la Agencia Estatal de Investigación (AEI), España y FEDER. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. ISBN 978-3-11-073962-6 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-073627-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-073704-2 ISSN 0178-7489 https://doi.org/10.1515/9783110736274 This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-No-Derivatives 4.0 License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. Library of Congress Control Number: 2021934666 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Milena Rodríguez Gutiérrez, published by de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston. The book is published open access at www.degruyter.com. Typesetting: Integra Software Services Pvt. Ltd. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com Una mujer escribe este poema Carilda Oliver Labra Índice Milena Rodríguez Gutiérrez Una mujer escribe este poema. -

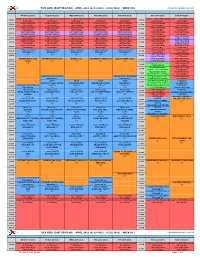

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - APRIL 2021 (4/12/2021 - 4/18/2021) - WEEK #16 Date Updated:3/25/2021 2:29:43 PM MON (4/12/2021) TUE (4/13/2021) WED (4/14/2021) THU (4/15/2021) FRI (4/16/2021) SAT (4/17/2021) SUN (4/18/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO -

THE GETAWAY GIRL: a NOVEL and CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By

THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION By EMILY CHRISTINE HOFFMAN Bachelor of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 1999 Master of Arts in English University of Kansas Lawrence, Kansas 2002 Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of the Oklahoma State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY December, 2009 THE GETAWAY GIRL: A NOVEL AND CRITICAL INTRODUCTION Dissertation Approved: Jon Billman Dissertation Adviser Elizabeth Grubgeld Merrall Price Lesley Rimmel Ed Walkiewicz A. Gordon Emslie Dean of the Graduate College ii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I would like to express my appreciation to several people for their support, friendship, guidance, and instruction while I have been working toward my PhD. From the English department faculty, I would like to thank Dr. Robert Mayer, whose “Theories of the Novel” seminar has proven instrumental to both the development of The Getaway Girl and the accompanying critical introduction. Dr. Elizabeth Grubgeld wisely recommended I include Elizabeth Bowen’s The House in Paris as part of my modernism reading list. Without my knowledge of that novel, I am not sure how I would have approached The Getaway Girl’s major structural revisions. I have also appreciated the efforts of Dr. William Decker and Dr. Merrall Price, both of whom, in their role as Graduate Program Director, have generously acted as my advocate on multiple occasions. In addition, I appreciate Jon Billman’s willingness to take the daunting role of adviser for an out-of-state student he had never met. Thank you to all the members of my committee—Prof. -

GULDEN-DISSERTATION-2021.Pdf (2.359Mb)

A Stage Full of Trees and Sky: Analyzing Representations of Nature on the New York Stage, 1905 – 2012 by Leslie S. Gulden, M.F.A. A Dissertation In Fine Arts Major in Theatre, Minor in English Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Texas Tech University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Approved Dr. Dorothy Chansky Chair of Committee Dr. Sarah Johnson Andrea Bilkey Dr. Jorgelina Orfila Dr. Michael Borshuk Mark Sheridan Dean of the Graduate School May, 2021 Copyright 2021, Leslie S. Gulden Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I owe a debt of gratitude to my Dissertation Committee Chair and mentor, Dr. Dorothy Chansky, whose encouragement, guidance, and support has been invaluable. I would also like to thank all my Dissertation Committee Members: Dr. Sarah Johnson, Andrea Bilkey, Dr. Jorgelina Orfila, and Dr. Michael Borshuk. This dissertation would not have been possible without the cheerleading and assistance of my colleague at York College of PA, Kim Fahle Peck, who served as an early draft reader and advisor. I wish to acknowledge the love and support of my partner, Wesley Hannon, who encouraged me at every step in the process. I would like to dedicate this dissertation in loving memory of my mother, Evelyn Novinger Gulden, whose last Christmas gift to me of a massive dictionary has been a constant reminder that she helped me start this journey and was my angel at every step along the way. Texas Tech University, Leslie S. Gulden, May 2021 TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGMENTS………………………………………………………………ii ABSTRACT …………………………………………………………..………………...iv LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………..v I. -

Análisis Discursivo De Las Líricas Del Rock Argentino En La “Primavera Democrática” (1983 - 1986)

Si tienes voz, Análisis discursivo de las líricas del r oc k ar g entino tienes palabras Federico Rodríguez Lemos en la “primavera democr ática” Cristian Secul Giusti (1983 - 1986) Universidad Nacional de La Plata Facultad de Periodismo y Comunicación Social Licenciatura en Comunicación Social Tesis de Grado Si tienes voz, tienes palabras Análisis discursivo de las líricas del rock argentino en la “primavera democrática” (1983 - 1986) Autores: Federico Rodríguez Lemos Cristian Secul Giusti Directora: Susana Souilla Agosto, 2011 Facultad de Periodismo y Comunicación Social Universidad Nacional de La Plata La Plata, Agosto de 2011 Estimados miembros del Consejo Académico S / D Tengo el agrado de dirigirme a ustedes a los efectos de dejar constancia de que los alumnos Cristian Secul Giusti y Federico Rodríguez Lemos han concluido su tesis de licenciatura bajo mi dirección. En el trabajo “Si tienes voz, tienes palabras: análisis discursivo de las líricas del rock argentino en la “primavera democrática” (1983-1986)”, los tesistas han elaborado un cuidadoso análisis de letras de rock a partir de las herramientas teórico metodológicas del análisis del discurso y han consultado una extensa bibliografía no sólo de análisis discursivo sino también de las ciencias sociales en general. Considero pertinente destacar que durante todo el proceso de investigación y escritura de la tesis, los alumnos Secul Giusti y Rodríguez Lemos han demostrado responsabilidad, entusiasmo, curiosidad y una gran disposición para revisar su producción, corregir diversos aspectos formales y de contenido y proponer ideas creativas e interesantes. Estas cualidades y actitudes les han permitido experimentar un proceso de crecimiento en sus habilidades analíticas y reflexivas. -

![Downloaded by [New York University] at 12:41 13 August 2016 the Interactive World of Severe Mental Illness](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7402/downloaded-by-new-york-university-at-12-41-13-august-2016-the-interactive-world-of-severe-mental-illness-2167402.webp)

Downloaded by [New York University] at 12:41 13 August 2016 the Interactive World of Severe Mental Illness

Downloaded by [New York University] at 12:41 13 August 2016 The Interactive World of Severe Mental Illness In our society, medication is often seen as the treatment for severe mental illness, with psychotherapy a secondary treatment. However, quality social interaction may be as important for the recovery of those with severe mental illness as are treatments. This volume makes this point while describing the emotionally moving lives of eight individuals with severe mental illness as they exist in the U.S. mental health system. Offering social and psychologi- cal insight into their experiences, these stories demonstrate how patients can create meaningful lives in the face of great difficulties. Based on in-depth interviews with clients with severe mental illness, this volume explores which structures of interaction encourage growth for people with severe mental illness and which trigger psychological damage. It con- siders the clients’ relationships with friends, family, peers, spouses, lovers, co-workers, mental health professionals, institutions, the community, and society as a whole. It focuses specifically on how structures of social interac- tion can promote or harm psychological growth, and how interaction dynam- ics affect the psychological well-being of individuals with severe mental illness. Diana Semmelhack is Professor of Behavioral Medicine at Midwestern Uni- versity and a Board Certified Clinical Psychologist. She has done extensive research on group work. Larry Ende received his MSW from the Jane Addams College of Social Work in Chicago and specializes in psychodynamically oriented therapy with chil- dren and adolescents and with severely mentally ill adults. He has a Ph.D in Literature from SUNY Buffalo. -

Obsesiones Y Compulsiones

Comentarios elogiosos previos a la publicación de El pensamiento es lo que cuenta “Tan inspirador como instructivo, el inquebrantable relato de Jared Kant sobre su lucha contra el TOC en la adolescencia debería ser lectura obligatoria para aquellos cuyas vidas han sido afectadas por el trastorno. Por su franqueza y trascendencia, el libro puede cambiar innumerables vidas”. —Jeff Bell, autor de Rewind Replay, Repeat: A Memoir of Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder “¡Un libro extraordinario! Jared Kant y sus coautores han logrado una descripción reveladora y directa del TOC. El libro refleja una cruda realidad pero, a la vez, brinda muchísimo apoyo y tranquilidad. Admiro el coraje y la predisposición de Jared para permitir que el mundo vea su caída en esta terrible enfermedad y su posterior recuperación. Los jóvenes que padecen el TOC verán que la información incluida en el libro es explicativa, aterradora, graciosa y esperanzadora. En ciertos momentos, la narrativa conjuga todas estas características al mismo tiempo. Si eres un adolescente o joven adulto que padece el TOC, este libro es lectura obligatoria”. —David F. Tolin, Ph.D., director, Anxiety Disorders Center, The Institute of Living; profesor adjunto, Facultad de Medicina de la Universidad de Yale (Yale University School of Medicine) y autor de Buried in Treasures: Help for Compulsive Acquiring, Saving, and Hoarding “El pensamiento que sí importa es The Catcher in the Rye (El guardián entre el centeno) para adolescentes y adultos jóvenes que padecen el TOC. Narra la historia del lector y del autor a la vez. Luego de leer el libro, la persona que padece el TOC ya no estará solo y contará con información sobre las maneras de manejar la enfermedad”. -

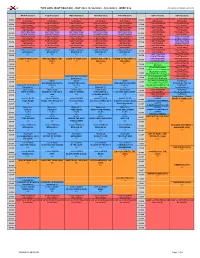

MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM

TLEX GRID (EAST REGULAR) - MAY 2021 (4/26/2021 - 5/2/2021) - WEEK #18 Date Updated:4/16/2021 2:24:45 PM MON (4/26/2021) TUE (4/27/2021) WED (4/28/2021) THU (4/29/2021) FRI (4/30/2021) SAT (5/1/2021) SUN (5/2/2021) SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM SHOP LC (PAID PROGRAM 05:00A 05:00A NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 05:30A 05:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:00A 06:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 06:30A 06:30A (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:00A 07:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 07:30A 07:30A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (SUBNETWORK) PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM PAID PROGRAM 08:00A 08:00A (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) (NETWORK) CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO CERRADO CASO -

Faulkner's God

FAULKNER’S GOD & Other Perspectives To My Brother Arne "Memory believes before knowing remembers ....” –Light in August CONTENTS: Preface 2 1. Faulkner and Holy Writ: The Principle of Inversion 4 2. Music: Faulkner's “Eroica" 20 3. Liebestod: Faulkner and The Lessons of Eros 34 4. Between Truth and Fact: Faulkner’s Symbols of Identity 61 5. Transition: Faulkner’s Drift From Freud to Marx 79 6. Faulkner’s God: A Jamesian Perspective 127 SOURCES 168 INDEX 173 * For easier revision and reading, I have changed the format of the original book to Microsoft Word. 2 PREFACE "With Soldiers' Pay [his first novel] I found out writing was fun," Faulkner remarked in his Paris Review interview. "But I found out afterward that not only each book had to have a design but the whole output or sum of an artist's work had to have a design." In the following pages I have sought to illuminate that larger design of Faulkner's art by placing the whole canon within successive frames of thought provided by various sources, influences, and affinities: Holy Writ, music, biopsychology, religion, Freud/Marx, William James. In the end, I hope these essays may thereby contribute toward revealing in Faulkner's work what Henry James, in "The Figure in the Carpet," spoke of as "the primal plan; some thing like a complex figure in a Persian carpet .... It's the very string . .my pearls are strung upon.... It stretches ... from book to book." I wish to acknowledge my debt to William J. Sowder for his discussion of the "Sartrean stare" in "Colonel Thomas Sutpen as Existentialist Hero" in American Literature (January 1962); to James B.