Competing While Injured: What Wrestlers Do and Why a THESIS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

State Athletic Commission 10/25/13 523

523 CMR: STATE ATHLETIC COMMISSION Table of Contents Page (523 CMR 1.00 THROUGH 4.00: RESERVED) 7 523 CMR 5.00: GENERAL PROVISIONS 31 Section 5.01: Definitions 31 Section 5.02: Application 32 Section 5.03: Variances 32 523 CMR 6.00: LICENSING AND REGISTRATION 33 Section 6.01: General Licensing Requirements: Application; Conditions and Agreements; False Statements; Proof of Identity; Appearance Before Commission; Fee for Issuance or Renewal; Period of Validity 33 Section 6.02: Physical and Medical Examinations and Tests 34 Section 6.03: Application and Renewal of a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant 35 Section 6.04: Initial Application for a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant New to Massachusetts 35 Section 6.05: Application by an Amateur for a License as a Professional Unarmed Combatant 35 Section 6.06: Application for License as a Promoter 36 Section 6.07: Application for License as a Second 36 Section 6.08: Application for License as a Manager or Trainer 36 Section 6.09: Manager or Trainer May Act as Second Without Second’s License 36 Section 6.10: Application for License as a Referee, Judge, Timekeeper, and Ringside Physician 36 Section 6.11: Application for License as a Matchmaker 36 Section 6.12: Applicants, Licensees and Officials Must Submit Material to Commission as Directed 36 Section 6.13: Grounds for Denial of Application for License 37 Section 6.14: Application for New License or Petition for Reinstatement of License after Denial, Revocation or Suspension 37 Section 6.15: Effect of Expiration of License on -

China Military Strategy

Cover China’s strategic thought is strongly influenced by three authors: Sun Tzu, Karl Marx, and Mao Zedong, according to Chinese sources. The methodology and philosophy of these men impact how Chinese strategists consider their battlefield context and accordingly develop their plans and procedures for the conduct of military operations. The views expressed in this document are those of the author and do not reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defense or the US government. The author works for the Foreign Military Studies Office (FMSO), Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. FMSO is a component of the US Army's Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC). The FMSO does strategic, guidance-driven, unclassified research and analysis of the foreign perspective of unconsidered/understudied security issues of the military operational environment. FMSO is the Army’s principal unclassified researcher, leader educator, and operational-support resource regarding the foreign perspective of the Operational Environment, and the Army’s leading advanced open source education developer, provider, and collaboration organization. TIMOTHY L. THOMAS FOREIGN MILITARY STUDIES OFFICE (FMSO) FORT LEAVENWORTH, KS 2014 TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION .................................................................................. 1 PART ONE: WHAT IS STRATEGY? ................................................. 9 CHAPTER ONE: CHINA’S MILITARY STRATEGY: WHERE KARL TRUMPS CARL ...................................................................... 11 Introduction -

Jackie Goes Home Young Working-Class Women: Higher Education, Employment and Social (Re)Alignment

Jackie Goes Home Young Working-Class Women: Higher Education, Employment and Social (Re)Alignment Laura Jayne Bentley, BA (Hons) A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the University of the West of England, Bristol for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Faculty of Arts, Creative Industries and Education Department of Education and Childhood Supervised by Associate Professor Richard Waller and Professor Harriet Bradley February 2020 Word count: 83,920 i Abstract This thesis builds on and contributes to work in the field of sociology of education and employment. It provides an extension to a research agenda which has sought to examine how young people’s transitions from ‘undergraduate’ to ‘graduate’ are ‘classed’ processes, an interest of some academics over the previous twenty-five years (Friedman and Laurison, 2019; Ingram and Allen, 2018; Bathmaker et al., 2016; Burke, 2016a; Purcell et al., 2012; Tomlinson, 2007; Brown and Hesketh, 2004; Brown and Scase, 1994). My extension and claim to originality are that until now little work has considered how young working-class women experience such a transition as a classed and gendered process. When analysing the narratives of fifteen young working-class women, I employed a Bourdieusian theoretical framework. Through this qualitative study, I found that most of the working-class women’s aspirations are borne out of their ‘experiential capital’ (Bradley and Ingram, 2012). Their graduate identity construction practices and the characteristics of their transitions out of higher education were directly linked to the different quantity and composition of capital within their remit and the (mis)recognition of this within various fields. -

Issue #46, March 2020 ISSN 22064907 (Online)

RPG REVIEW Issue #46, March 2020 ISSN 2206-4907 (Online) FUDGE, FATE,& FRIENDS FUDGE, Fate, and Spirit of the Century Reviews ¼ Fate Core Hacks .. Robots of Diaspora ¼ Collaborative Legends of Anglerre ¼ Undying Empire ¼ Gulliver©s Trading Company .. and more! 1 RPG REVIEW ISSUE 46 March 2020 Table of Contents ADMINISTRIVIA.........................................................................................................................................................2 EDITORIAL AND COOPERATIVE NEWS................................................................................................................2 FUDGE AND FATE REVIEWS...................................................................................................................................4 SOME HACKS FOR FATE CORE.............................................................................................................................14 TECHNOLOGY AND ROBOTS OF THE DIASPORA............................................................................................16 THE BLACK BULL, A GULLIVER©S TRADING COMPANY JOURNEY............................................................25 LEGENDS OF ANGLERRE : COLLABORATIVE CAMPAIGNS..........................................................................34 LEGENDS OF ANGLERRE : UNDYING EMPIRES................................................................................................44 CRPG REVIEW : LINKS AWAKENING REMAKE................................................................................................57 -

Insert Front Page Gladiatorial Combat in Ancient Rome

GLADIATOR Insert Front Page GLADIATOR Gladiatorial Combat in Ancient Rome Colosseum Edition (ver XXX) I Colosseum Edition For Holly, Ryan & Tristen Mei gaudium, mei amor, mei vita! GLADIATOR TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS 22. SPECIAL ATTACKS & DEFENSES - XV 23. UNARMED COMBAT - XV 1. INTRODUCTION - II 24. TWO-HANDED FIGHTING - XVI BASIC GAME 25. ARENA WALLS - XVI 2. GAME COMPONENTS - III 26. CLEAVING - XVI 3. GLADIATOR LOG SHEET – III 27. TEAM COMBAT - XVI 4. MATCH PREPARATION – IV 28. GLADIATOR VS BEAST - XVII 5. SUMMARY OF PLAY – V 29. SOLITAIRE GLADIATOR - XVIII 6. FACING – V CAMPAIGN GAME 7. MOVEMENT – V 30. ARRANGING MATCHES - XX 8. COLLISIONS – VI 31. EXPERIENCE - XX 9. COMBAT – VII 32. INJURIES - XXI 10. WOUNDS – VIII 33. SOCIAL ORIGIN - XXI 11. STUN – IX 34. CUSTOMIZED ARMOR - XXI 12. SHIELD DAMAGE – X 35. PRESTIGE - XXI 13. WEAPON & SHIELD LOSS – X 36. TALENTS - XXI 14. KNEELING – XI 37. LANISTAS - XXII 15. STUMBLE – XI 16. PRONE – XI APPENDIX 17. ENDURANCE – XI GLADIATOR HISTORY - XXIII 18. MOMENT OF TRUTH – XI COMMON ROMAN NAMES - XXIV ADVANCED GAME BIBLIOGRAPHY - XXV PRINTING NOTES - XXV 19. GLADIATOR FIGHTING STYLES - XII GLADIATOR CREDITS - XXV 20. USE OF THE NET & TRIDENT - XII 21. USE OF OPTIONAL WEAPONS - XIV In GLADIATOR, each player assumes the role of a 1. INTRODUCTION - gladiator fighting in the Roman arena. Players secretly plot their gladiator’s movement and combat actions in an effort to outmaneuver, and outfight their opponents. Careful planning, maneuvering, and luck are needed to defeat your opponent and survive for another day. Many of the concepts in GLADIATOR require practice and experience gained only through repeated play. -

A Spectator=S Guide to Water Polo

A Spectator’s Guide to Water Polo by: Peter W. Pappas, Ph.D. This document may be copied and distributed freely, without limitation, in either printed or electronic form, for “personal use.” This document may not be reproduced in any form and sold for profit without the prior, written consent of the author. Version: 5.0 Released: August 1, 2006 Copyright 2006 by Peter W. Pappas A Spectator’s Guide to Water Polo Page 2 Preface (Version 5.0) In 2005, FINA (Federation Internationale de Natation) adopted a number of new water polo rules. These new rules have been adopted in their entirety by USA Water Polo (USAWP), and many of the rules have also been adopted by the National Collegiate Athletic Association (NCAA) and the National Federation of State High School Associations (NFHS). Thus, these new rules are now used in virtually all water polo competitions, and A Spectator’s Guide to Water Polo has been re-written to conform with and include appropriate references to these new rules. All rule numbers and figures in this version of the Guide have been updated to conform to the most current versions of the rules. These include the 2005-2009 USAWP rules, the 2006-2007 NCAA rules, and the 2006-2007 NISCA rules. Finally, I have moved all files to a new server. An electronic file (.pdf) of Version 5.0 of the Guide can be found at: oaa.osu.edu/coam/guide/home.html This Guide may be copied and distributed freely, without limitation, in either printed or electronic form, for “personal use.” This document may not be reproduced in any form and sold for profit without the prior, written consent of the author. -

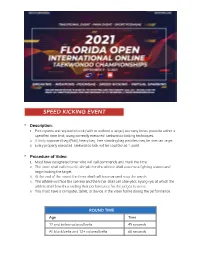

Speed Kicking Event

SPEED KICKING EVENT Description: Participants are required to kick a target as many times possible within a specifed time limit, using correctly executed Taekwondo Kicking Techniques delivered to the same body-level height as athlete performing. They can kick a “Bob” (body opponent bag), Heavy Bag, Free Standing Bag Paddles, or the air. They are able to use any taekwondo kicking techniques. If they hang their leg it must be within 3 seconds. Every kick will be counted as 1. Procedure of Video: Must have designated timer who will call commands and mark the time. The Athlete shall face the camera and the timer shall call cha-ryeot, kyeong-rye. After bowing the athlete shall turn to face the kicking target, holder or to the side. The timer shall call choonbi, shi-jak then the athlete shall assume a fghting stance and begin kicking the target. At the end of the round the timer shall call keu-man and stop the watch. The athlete will then face the camera and the timer shall call char-yeot, kyung-rye, at which the athlete shall bow thus ending their performance for the judges to score. You must have a computer, tablet, or device in the video frame during the performance. ROUND TIME AGE: TIME: 12 and Below Colored Belts 45 Seconds All Black Belts and (12+) Colored Belts 60 Seconds SCORING: Judges will score legal kicks that are executed to same body and head level height as athlete. Three referees will count the number of athlete’s kick and we will average score. -

The Martial Arts of Medieval Europe

THE MARTIAL ARTS OF MEDIEVAL EUROPE Brian R. Price Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2011 APPROVED: Laura Stern, Major Professor Geoffrey Wawro, Committee Member Adrian R. Lewis, Committee Member Robert M. Citino, Committee Member Stephen Forde, Committee Member Richard McCaslin, Chair of the Department of History James D. Meernik, Acting Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Price, Brian R. The Martial Arts of Medieval Europe. Doctor of Philosophy (History), August 2011, 310 pp., 2 tables, 6 illustrations, bibliography, 408 titles. During the late Middle Ages and into the Renaissance, fighting books—Fechtbücher— were produced in northern Italy, among the German states, in Burgundy, and on the Iberian peninsula. Long dismissed by fencing historians as “rough and untutored,” and largely unknown to military historians, these enigmatic treatises offer important insights into the cultural realities for all three orders in medieval society: those who fought, those who prayed, and those who labored. The intent of this dissertation is to demonstrate, contrary to the view of fencing historians, that the medieval works were systematic and logical approaches to personal defense rooted in optimizing available technology and regulating the appropriate use of the skills and technology through the lens of chivalric conduct. I argue further that these approaches were principle-based, that they built on Aristotelian conceptions of arte, and that by both contemporary and modern usage, they were martial arts. Finally, I argue that the existence of these martial arts lends important insights into the world-view across the spectrum of Medieval and early Renaissance society, but particularly with the tactical understanding held by professional combatants, the knights and men-at-arms. -

Physiological Demands and Time-Motion Analysis of Simulated Elite Karate Kumite Matches

Physiological demands and time-motion analysis of simulated elite karate kumite matches ELSABÉ LE ROUX In fulfilment of the degree MAGISTER ARTIUM (HUMAN MOVEMENT SCIENCE) In the Faculty of Humanities (Department of Exercise and Sport Sciences) At the University of the Free State Study Leader: Prof. F.F. Coetzee Co-Study Leader: Dr. C.J. Jansen van Rensburg Bloemfontein January 2015 DECLARATION THESIS TITLE: Physiological demands and time-motion analysis of simulated elite karate kumite matches I, Elsabé le Roux, hereby declare that the work on which this dissertation is based is my original work (except where acknowledgments indicate otherwise) and that neither the whole work nor any part of it has been, is being, or is to be submitted for another degree in this or any other university. I empower the university to reproduce for the purpose of research either the whole or any portion of the contents in any matter whatsoever. SIGNATURE: _______________________________ DATE: _____________________________________ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank the following people for their contributions to this dissertation through their assistance in the data collection and analysis: To my promoter, Prof. F. F. Coetzee, I am eternally grateful to you for your supervision. Your assistance, guidance and input in this dissertation are greatly appreciated. To Prof. Robert Schall, University of the Free State, for your input and statistical support, for which I am truly grateful. To the Free State Sport Science Institute (FSSSI), for the utilization of their equipment, facilities and personnel. To Mr. Evert Venter, director of FSSSI, and Mr. Jan du Toit, deputy director of FSSSI, for supporting this research. -

FOITC Speedkicking, VS, Breaking

SPEED KICKING EVENT • Description: 1. Participants are required to kick (with or without a target) as many times possible within a specified time limit, using correctly executed Taekwondo kicking techniques. 2. A body opponent bag (Bob), heavy bag, free standing bag paddles may be used as target. 3. Every properly executed Taekwondo kick will be counted as 1 point. • Procedure of Video: 1. Must have designated timer who will call commands and mark the time. 2. The timer shall call choonbi, shi-jak then the athlete shall assume a fighting stance and begin kicking the target. 3. At the end of the round, the timer shall call keu-man and stop the watch. 4. The athlete will face the camera and the timer shall call char-yeot, kyung-rye, at which the athlete shall bow thus ending their performance for the judges to score. 5. You must have a computer, tablet, or device in the video frame during the performance. ROUND TIME Age Time 12 and below colored belts 45 seconds All black belts and 12+ colored belts 60 seconds Scoring: Judges will score legal kicks that are executed to same body and head level height as athlete. Three referees will count the number of athlete’s kick and we will average score. Every kick will be counted as 1 point. VIRTUAL SPARRING • Description: 1. Participants use controlled, correctly executed Taekwondo hand and kicking techniques delivered to a heavy bag equipped with head and body level target of the same height as the athlete. 2. You must have a body opponent bag (Bob), or Heavy Bag/ Free Standing Bag with tape marking head level. -

Philippines the Title Filipino Martial Arts (FMA) Refers to Several Styles, Methods, and Systems of Self-Defense That Include Armed and Unarmed Combat

now internationally known system of training performers using the princi- ples of techniques of Asian martial and meditation arts as a foundation for the psychophysiological process of the performer (see Zarrilli 1993, 1995). One example of the actual use of a martial art in contemporary the- ater performance is that of Yoshi and Company. In the 1970s Yoshi Oida, an internationally known actor with Peter Brook’s company in Paris, cre- ated a complete performance piece, Ame-Tsuchi, based on kendô. Yoshi used the rituals of combat and full contact exchanges as a theatrical vehi- cle for transmission of the symbolic meaning behind the Japanese origin myth that served as the text for the performance. Of the many examples from Asia per se, during the 1980s in India a number of dancers, choreographers, and theater directors began to make use of martial arts in training their companies or for choreography. Among some of the most important have been theater directors Kavalam Narayana Panikkar of Kerala, who used kalarippayattu in training his company, Sopanam, and Rattan Theyyam in Manipur, who made use of thang-ta. Among Indian choreographers, Chandralekha of Madras and Daksha Seth of Thiruvananthapuram have both drawn extensively on kalarippayattu in training their companies and creating their contemporary choreographies. Phillip Zarrilli See also Africa and African America; Capoeira; Form/Xing/Kata/Pattern Practice; Japan; Kalarippayattu; Mongolia; Thang-Ta References Elias, Norbert. 1972. “The Genesis of Sport as a Sociological Problem.” In Sport: Readings from a Sociological Perspective. Edited by Eric Dunning. Toronto: University of Toronto. Ghosh, M. 1956. Natyasastra. -

Contemporary Letter

Region One Training Class PO Box 10818, Pleasanton, March 28th and 29th, 2017 CA 94588 0800-1700 hours Law Enforcement Combatives Course Ground Control Fundamentals & Intro to Vehicle Tactics 16 Hour Training Course (2 day) @ CNOA-Region 1 Win the fight! Ground altercations are inherently high risk for officers with the potential for serious injury or death. Officers must understand the mechanics of a ground fight in order REGION 1 BOARD to survive. Risk can be mitigated through training and awareness. In this course, we will CHAIRMAN build confidence while reinforcing these important points: Doug Ulrich Santa Clara County Sheriff’s • You must fight to get to your feet Office • If you must be on the ground, have the confidence to survive and win VICE CHAIRMAN • Tom Moreno Weapon retention and positional awareness remain paramount San Jose P.D. • Gain positional advantage, control the threat and finish the fight SECRETARY In this course, we will cover common ground fighting positions, escapes, reversals, gaining Faye Maloney Hayward P.D. and maintaining control, weapon retention, submissions and handcuffing. This course will satisfy a Carotid Restraint Hold (Lateral Vascular Restraint) refresher and initial certification. TREASURER ***On day two, we will introduce vehicle combatives. Students will learn how to fight from insid Jose Marin Contra Costa Co. D.A.’s Office a vehicle. Topics will include; gaining dominant position, weapon retention and weapon disarming. We will be utilizing simunitions and force on force during the final portion of the SERGEANT-AT-ARMS course.*** Oscar Ortiz Napa County Sheriff’s Office Instructors: Nathan Mendes has been in Law Enforcement for 15 years and is certified through TRAINING (POST) and the Federal Law Enforcement Training Center (FLETC) to teach defensive tactics, impact COORDINATORS weapons, and chemical agents.