Under the Basho 2014

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Richard Flanagan's the Narrow Road to the Deep North and Matsuo

Coolabah, No.21, 2017, ISSN 1988-5946, Observatori: Centre d’Estudis Australians / Australian Studies Centre, Universitat de Barcelona Richard Flanagan’s The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Matsuo Basho’s Oku no Hosomichi Yasue Arimitsu Doshisha University [email protected] Copyright©2017 Yasue Arimitsu. This text may be archived and redistributed both in electronic form and in hard copy, provided that the author and journal are properly cited and no fee is charged, in accordance with our Creative Common Licence. Abstract. This paper investigates Australian author Richard Flanagan’s novel, The Narrow Road to the Deep North, and attempts to clarify the reason why Flanagan chose this title, which is linked to the travel writings of the Japanese author Matsuo Basho, for his novel. The novel focuses on the central character’s prisoner of war experience on the Thai-Burma Death Railway during World War II, and depicts the POW camp as well as cruel Japanese behaviour and atrocities in a realistic way. The work seems to provide a postcolonial framework in the sense that there is a colonial and postcolonial relationship between the colonizer, and the colonized. However, in this novel, the colonizer is Eastern, and the colonized is Western, and this fact reverses postcolonial theory which postulates a structure in which the colonizer is usually considered as Western and the colonized, Eastern. Postcolonial theory, thus, cannot be applied in this novel, which attempts to fuse the two opposites, the Western view and the Eastern view, through the work of the Japanese poet. As a result, Flanagan, in writing The Narrow Road to the Deep North, goes beyond being a postcolonial writer to become a writer in a globalizing age. -

Rhyming Pattern Selection in Japanese Short Poetry

Original Paper________________________________________________________ Forma, 21, 259–273, 2006 Statistical Prosody: Rhyming Pattern Selection in Japanese Short Poetry Kazuya HAYATA Department of Socio-Informatics, Sapporo Gakuin University, Ebetsu 069-8555, Japan E-mail address: [email protected] (Received August 5, 2005; Accepted August 2, 2006) Keywords: Quantitative Poetics, Rhyme, HAIKU, TANKA, Bell Number Abstract. Rhyme patterns of Japanese short poetry such as HAIKU, SENRYU, SEDOKAs, and TANKAs are analyzed by a statistical approach. Here HAIKU and SENRYU are poems composed of only seventeen syllables, which can be segmented into five, seven, and five syllables. As rhyming both head and end rhymes are considered. Analyses of sampled works of typical poets show that for the end rhyme composers prefere the avoided rhyming, whereas for the head rhyme they compose poems according to the stochastic law. Subsequently the statistical method is applied to a work of SEDOKAs as well as to those of TANKAs being written with three lines. Evaluation of the khi-square statistics shows that for a certain work of TANKAs the feature being identical to that of HAIKU is seen. 1. Introduction Irrespective of languages, texts are categorized into proses and verses. Poems, in general, take the form of the latter. Conventional poetics has classified poems into a variety of forms such as a lyric, an epic, a prose, a long, and a short poem. One finds that in typical European poetry a sound on a site in a line is correlated to that on the same site in another line in an established form. Correlation among feet of lines is termed end rhyme in contrast to the head rhyme for the one among heads of lines (SAKAMOTO, 2002). -

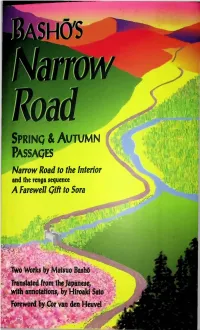

Basho's Narrow Road: Two Works by Matsuo Basho: Review

RESOURCES BOOK REVIEWS task for tormenting defenseless dwarf trees, and there is “Mr. Robert” At its most straightforward level, the work is Bash¬’s travel diary of (236–42) by Viki Radden, which recounts the gala reception given a five-month circuitous journey in 1689 from the capital Edo to to the newly-arrived English-language teacher in a small Japanese Kisakata in the north, along the coast of the Sea of Japan through town, and the comic confusion that ensues when the young man turns Niigata and Tsuruga, and back inland to √gaki. Sato includes a out ‘not’ to be an obese Mexican, as the townsfolk had somehow double-page map of the route showing the major stopping places— come to expect. a handy device to keep us attuned to the progress of the narrative and The Broken Bridge owes much to the aforementioned Donald its grounding in real terrain. In order to take in some uta-makura— Richie, who was instrumental in the volume’s production. I should “poetic pillows” or places charged with literary significance due to mention that the book begins with his fine introductory essay (9–16) repeated reference throughout history—he and his companion Sora and ends with his “Six Encounters” (342–53), a mini-anthology of forsake the high road for one “seldom used by people but frequented vignettes that in effect recapitulates the entire volume. by pheasants, rabbits, and woodcutters” (83). They take a wrong turn In conclusion, one imagines any number of interesting applications but are treated to a panoramic view of Mount Kinka across the sea of The Broken Bridge, either in whole or in part, in courses concerning from Ishinomaki port. -

3Ce70fcf2def46fef69305cd567fb

REDISCOVERING BASHO ■i M ft . ■ I M S 0 N ;V is? : v> V,•• I 8 C: - :-4 5 1k: ; fly j i- -i-h. • j r-v?-- m &;.*! .! * sg ‘Matsuo Basho’ (Basho-o Gazo) painting by Ogawa Haritsu (1663-1747) (Wascda University Library, Tokyo) REDISCOVERING BASHO A 300TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION f,:>; TED BY r.N HENRY GILL ' IDREW GERSTLE GLOBAL ORIENTAL REDISCOVERING BASHO A 300TH ANNIVERSARY CELEBRATION Edited by Stephen Henry Gill C. Andrew Gcrstlc First published 1999 by GLOBAL ORIENTAL PO Box 219 Folkestone Kent CT20 3LZ Global Oriental is an imprint of Global Boohs Ltd © 1999 GLOBAL BOOKS LTD ISBN 1-901903-15-X All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission in writing from the Publishers, except for the use of short extracts in criticism. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A CIP catalogue entry for this book is available from the British Library Set in Bembo llpt by Bookman, Hayes, Middlesex Printed and bound in England by Bookcraft Ltd., Midsomer Norton, Avon Contents List of Contributors vii 1. Introduction - Shepherd’s Purse: A Weed for Basho 1 STEPHEN HENRY GILL 2. An Offering of Tea 13 MICHAEL BIRCH ; o and I: The Significance of Basho 300 Years after 16 his Death . - 'NEHIKO HOSHINO 4. ■ seiuation of Basho in the Arts & Media 24 : C HEN HENRY GILL 5. ri : ao has been Found: His Influence on Modem 52 Japanese Poetry VlIROFUMI WADA 6. Laughter in Japanese Haiku 63 NOBUYUKI YUASA 7. -

Matsuo Bashōs Poetic Spaces: Exploring Haikai Intersections Edited by Eleanor Kerkhan Pargrave Macmillan, $95.00

Matsuo Bashōs Poetic Spaces: Exploring Haikai Intersections Edited by Eleanor Kerkhan Pargrave Macmillan, $95.00 Haiku is a well-known in much of the world as a short poem, usually written in three lines. Traditionally, in Japanese at least, it's laid out in a 5-7-5 sequence and includes a seasonal reference. The word "haiku" was first popularized by Masoka Shiki (1867-1902), in order to distinguish it from the linked verses, renga, to which it was originally attached. Most of the contributors to Matsuo Basho's Poetic Spaces use the term haikai, the genre's original name, an abbreviation of haikai no renga. I will use the modern term, haiku, except when quoting. During the rule of Japan's Tokugawa shogunate (1600-1868), the country was unified and finally at peace, although the price was an iron-fisted feudal social order. Jesuit missionaries from Portugal and their Japanese converts were executed, and except for a small colony of Dutch traders confined to the port of Nagasaki, foreign trade had been banned. Into this climate of isolation and xenophobia, in 1644 Matsuo Kinsaku was born in the village of Ueno, thirty miles southeast of Kyoto. As Matsuo Bashō---he took his pen name from a bashō (banana) tree that grew outside a hut he lived in for two years---he built a reputation as a haiku teacher. What set him apart from the others was his freeing of haiku from renga, making it a genre in its own right. He is also known for his tireless wayfaring to places made famous by former poets (utamakura), and for visiting poets in different provinces, along with patrons with whom he participated in evenings of linked verse composing. -

Biblio:Basho-27S-Haiku.Pdf

Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Matsuo Basho¯, 1644–1694. [Poems. English. Selections] Basho¯’s haiku : selected poems by Matsuo Basho¯ / translated by David Landis Barnhill. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6165-3 — 0-7914-6166-1 1. Haiku—Translations into English. 2. Japanese poetry—Edo period, 1600–1868—Translations into English. I. Barnhill, David Landis. II. Title. PL794.4.A227 2004 891.6’132—dc22 2004005954 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Basho¯’s Haiku Selected Poems by Matsuo Basho¯ Matsuo Basho¯ Translated by, annotated, and with an Introduction by David Landis Barnhill STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS for Phyllis Jean Schuit spruce fir trail up through endless mist into White Pass sky Contents Preface ix Selected Chronology of the Life of Matsuo Basho¯ xi Introduction: The Haiku Poetry of Matsuo Basho¯ 1 Translation of the Hokku 19 Notes 155 Major Nature Images in Basho¯’s Hokku 269 Glossary 279 Bibliography 283 Index to Basho¯’s Hokku in Translation 287 Index to Basho¯’s Hokku in Japanese 311 Index of Names 329 vii Preface “You know, Basho¯ is almost too appealing.” I remember this remark, made quietly, offhand, during a graduate seminar on haiku poetry. -

English Translations of Hokku from Matsuo Basho's Oku No Hosomichi

xi The Beat of Different Drummers: English Translations of Hokku from Matsuo Basho's Oku no hosomichi Mark Jewel (Waseda University) Haiku is without question Japan's most successful literary export. Indeed, along with judo in the field of sports and, more recently, anime and video games, haiku is one of only a handful of Japanese cultural products that can be said to have acquired an international following of any significant size. Haiku in English boasts a history in translation of over one hundred years, and an active "haiku community" of original poets that dates back at least as far as the first regularly published magazines of English haiku in the 1960s. As one indication of just how popular English haiku has become in the past quarter century, it may suffice to point out that more than ten single volume anthologies of haiku in English have been published since the first such anthology- Cor van den Heuval's The Haiku Anthology (Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books)--came out in 1974. 1 Small wonder it may seem, the~ that the poetic travel diary Oku no hosomichi, by Matsuo Bash6 (1654-1694), which contains fifty ofBashO's hokku, has been translated into English more frequently than any other major work of Japanese literature, with no fewer than eight complete published versions. 2 Part of the purpose of this paper is to suggest that, in fact, eight different versions cannot be called an overabundance in this case. But before turning to an examination of some of the hokku from Okuno hosomichi to help justify this assertion, I think it will be helpful to review the changing fortunes of haiku in English over the past hundred years, for the current high regard in which BashO's poetry is held by both translators and English-language haiku poets by no means reflects its reputation among the first serious foreign students of Japanese literature. -

The Pilgrim's Ideal in Basho's Oku No Hosomichi

VIEWS AND REVIEWS Awakening to the High/Retuming to the Low: The Pilgrim’s Ideal in Basho’s Oku no Hosomichi DENNIS G. HARGISS INTRODUCTION HERE is a tremendous disparity among scholars concerning the relationship between Matsuo Basho (1644-1694) and Buddhism. Many discus sionsT in this debate revolve especially around the nature and extent of Basho’s involvement in Z e n .1 On the one hand, R.H. Blyth and Heinrich Dumoulin point out Basho’s “deep interest in Zen”2 3or “Zen lifestyle”;2 the Japanese literary scholar Yagi Kametard describes Basho’s oeu vre as “permeated with the mind of Zen”;4 and 1 William LaFleur notes this situation in an article entitled “Japanese Religious Poetry" in The Encyclopedia of Religion when he states: “Scholarly opinion differs about the Zen involvement of the principal haiku poet, Matsuo Basho." William LaFleur, “Japanese Religious Poetry” in Mircea Eliade, ed., The Encyclopedia of Religion vol. 11 (New York: Macmillan, 1987), 381. 2 Reginald Horace Blyth, Haiku vol. 1 (Tokyo: Hokuseido Press, 1949), 27. Blyth not only notes the “flavour o f Zen” in some o f Basho’s poems, but even states that haiku are “a form o f Zen” which "are to be understood from the Zen point o f view” (i.e., from “that state o f mind in which we are not separated from other things, and yet retain our own individuality and personal peculiarities”). See Blyth, 26-27; iii-iv. 3 From Heinrich Dumoulin’s article “Zen” in Eliade, Encyclopedia o f Religion, vol. 15, 566. -

Volume XI Number 2 CONTENTS Fall 2003

Volume XI Number 2 CONTENTS Fall 2003 From the Editors' Desk 編纂者から 1 EMJ Renewals, Call for Proposals, EMJNet at the AAS 2004 (with abstracts of presentations) Articles 論文 Collaboration In Haikai: Chōmu, Buson, Issa Collaboration In Haikai: Chōmu, Buson, Issa: An Introduction Cheryl Crowley 3 Collaboration in the "Back to Bashō" Movement: The Susuki Mitsu Sequence of Buson's Yahantei School Cheryl Crowley 5 Collaboration of Buson and Kitō in Their Cultural Production Toshiko Yokota 15 The Evening Banter of Two Tanu-ki: Reading the Tobi Hiyoro Sequence Scot Hislop 22 Collaborating with the Ancients: Issues of Collaboration and Canonization in the Illustrated Biography of Master Bashō Scott A. Lineberger 32 Editors Philip C. Brown Ohio State University Lawrence Marceau University of Delaware Editorial Board Sumie Jones Indiana University Ronald Toby University of Illinois For subscription information, please see end page. The editors welcome preliminary inquiries about manuscripts for publication in Early Modern Japan. Please send queries to Philip Brown, Early Modern Japan, Department of History, 230 West 17th Avenue, Colmbus, OH 43210 USA or, via e-mail to [email protected]. All scholarly articles are sent to referees for review. Books for review and inquiries regarding book reviews should be sent to Law- rence Marceau, Review Editor, Early Modern Japan, Foreign Languages & Lit- eratures, Smith Hall 326, University of Deleware, Newark, DE 19716-2550. E-mail correspondence may be sent to [email protected]. Subscribers wishing to review books are encouraged to specify their interests on the subscriber information form at the end of this volume. The Early Modern Japan Network maintains a web site at http://emjnet.history.ohio-state.edu/. -

Basho's Haikus

Basho¯’s Haiku Basho¯’s Haiku Selected Poems by Matsuo Basho¯ Matsuo Basho¯ Translated by, annotated, and with an Introduction by David Landis Barnhill STATE UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK PRESS Published by State University of New York Press, Albany © 2004 State University of New York All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner whatsoever without written permission. No part of this book may be stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means including electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise without the prior permission in writing of the publisher. For information, address State University of New York Press, 90 State Street, Suite 700, Albany, NY 12207 Production by Kelli Williams Marketing by Michael Campochiaro Library of Congress Cataloging in Publication Data Matsuo Basho¯, 1644–1694. [Poems. English. Selections] Basho¯’s haiku : selected poems by Matsuo Basho¯ / translated by David Landis Barnhill. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 0-7914-6165-3 — 0-7914-6166-1 1. Haiku—Translations into English. 2. Japanese poetry—Edo period, 1600–1868—Translations into English. I. Barnhill, David Landis. II. Title. PL794.4.A227 2004 891.6’132—dc22 2004005954 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 for Phyllis Jean Schuit spruce fir trail up through endless mist into White Pass sky Contents Preface ix Selected Chronology of the Life of Matsuo Basho¯ xi Introduction: The Haiku Poetry of Matsuo Basho¯ 1 Translation of the Hokku 19 Notes 155 Major Nature Images in Basho¯’s Hokku 269 Glossary 279 Bibliography 283 Index to Basho¯’s Hokku in Translation 287 Index to Basho¯’s Hokku in Japanese 311 Index of Names 329 vii Preface “You know, Basho¯ is almost too appealing.” I remember this remark, made quietly, offhand, during a graduate seminar on haiku poetry. -

Matsuo Bashō's Narrow Road to the Deep North

Bashō Matsuo Bashō’s Narrow Road to the Deep North Oku no Hosomichi Three genres: travelogue; picaresque; haibun ••• Bashō’s Narrow Road is, arguably, the most famous and influential work of Japanese literature. In essence, the piece belongs to the travelogue genre, being Bashō’s first-person account of a journey (or pilgrimage of sorts) that he undertook in 1689 with fellow-poet Kawai Sora (also known as Soga) as his companion. Narrow Road first appeared in 1702, after Bashō’s death (at around age 50, in 1694). Westerners sometimes refer to Bashō as the “Shakespeare of Japan.” ••• As with Voltaire’s Candide, a later work, Narrow Road conforms to the formula identified with the picaresque genre, namely: a central protagonist (Bashō) who, while experiencing a journey made up of didactic episodes (called “Stations” in this case) is informed by a mentor, also known as preceptor (or by several such individuals). Some of Bashō’s mentors are living people (e.g., Sora/Soga), but others are dead sages and poets whose influence continues to be felt at many of the sites that Bashō chooses to visit. ••• On the Narrow Road odyssey, Sora kept a journal, known as Sora’s Diary (or Sora Nikki), which was lost for many centuries until rediscovered in 1943. Details in Sora’s account sometimes differ from details in Bashō’s, suggesting that Bashō may have edited or “spun” elements of his content to make certain ideological points or even to hide certain potentially embarrassing details (e.g., a possible dalliance with a prostitute). Towards the end of Narrow Road, Sora finds himself “seized by an incurable pain in his stomach,” so he cannot finish out the journey with Bashō. -

Spring &Autumn

Spring & Autumn Passages Narrow Road to the Interior and the renga sequence A Farewell Qift to Sora iV-y, . p^: Two Works by Matsuo BasM Translated from the Japanese, with annotations, by Hiroaki Sato Foreword by Cor van den Heuvel '-f BASHO'S NARROW ROAD i j i ; ! ! : : ! I THE ROCK SPRING COLLECTION OF JAPANESE LITERATURE ; BaSHO'S Narrow Road SPRINQ & AUTUMN PASSAQES Narrow Road to the Interior AND THE RENGA SEQUENCE A Farewell Gift to Sora TWO WORKS BY MATSUO BASHO TRANSLATED FROM THE JAPANESE, WITH ANNOTATIONS, BY Hiroaki Sato FOREWORD BY Cor van den Heuvel STONE BRIDGE PRESS • Berkeley,, California Published by Stone Bridge Press, P.O, Box 8208, Berkeley, CA 94707 510-524-8732 • [email protected] • www.stoncbridgc.com Cover design by Linda Thurston. Text design by Peter Goodman. Text copyright © 1996 by Hiroaki Sato. Signature of the author on front part-title page: “Basho.” Illustrations by Yosa Buson reproduced by permission of Itsuo Museum. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form without permission from the publisher. Printed in the United States of America 10 987654321 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOG1NG-1N-PUBL1 CATION DATA Matsuo, BashO, 1644-1694. [Oku no hosomichi. English] Basho’s Narrow road: spring and autumn passages: two works / by Matsuo Basho: translated from the Japanese, with annotations by Hiroaki Sato. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. Contents: Narrow road to the interior and the renga sequence—A farewell gift to Sora. ISBN 1-880656-20-5 (pbk.) 1- Matsuo, Basho, 1644-1694—Journeys—Japan.