NOCINIOUSV3 EAST LONDON RECORD No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Appendix 2 Strategic CIL Project Appraisal Scoring Criteria Section 1

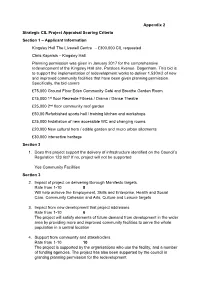

Appendix 2 Strategic CIL Project Appraisal Scoring Criteria Section 1 – Applicant Information Kingsley Hall The Livewell Centre - £300,000 CIL requested Chris Kapnisis – Kingsley Hall Planning permission was given in January 2017 for the comprehensive redevelopment of the Kingsley Hall site, Parsloes Avenue, Dagenham. This bid is to support the implementation of redevelopment works to deliver 1,530m2 of new and improved community facilities that have been given planning permission. Specifically, the bid covers £75,000 Ground Floor Eden Community Café and Breathe Garden Room £75,000 1st floor Recreate Fitness / Drama / Dance Theatre £25,000 2nd floor community roof garden £50,00 Refurbished sports hall / training kitchen and workshops £25,000 Installation of new accessible WC and changing rooms £20,000 New cultural herb / edible garden and micro urban allotments £30,000 interactive heritage Section 2 1. Does this project support the delivery of infrastructure identified on the Council’s Regulation 123 list? If no, project will not be supported Yes Community Facilities Section 3 2. Impact of project on delivering Borough Manifesto targets. Rate from 1-10 8 Will help achieve the Employment, Skills and Enterprise, Health and Social Care, Community Cohesion and Arts, Culture and Leisure targets 3. Impact from new development that project addresses Rate from 1-10 6 The project will satisfy elements of future demand from development in the wider area by providing more and improved community facilities to serve the whole population in a central location 4. Support from community and stakeholders Rate from 1-10 10 The project is supported by the organisations who use the facility, and a number of funding agencies. -

Sandars Lectures 2007: Conversations with Maps

SANDARS LECTURES 2007: CONVERSATIONS WITH MAPS Sarah Tyacke CB Lecture III: There are maps and there are maps – motives, markets and users As Christian Jacob put it ‘There are maps and there are maps’. More prosaically the nature of them depends on what you want the map or chart for and how you the reader perceive it? This third lecture is about what drove the cartographic activity internally and externally and how did it manifest itself in England and the rest of maritime Europe through its distributors, patrons and readers. This is probably the most challenging subject, first articulated in embryonic form as part of the history of cartography’s remit in the 1970s by David Woodward (as we saw in lecture I) and developed thereafter as the history of cartography took a ‘second turn’ and embraced social context. This ‘second turn’ challenged the inevitability of progress in cartography and understood that cartography was just as much a product of its society as other texts. In the case of Brian Harley he took this further arguing powerfully, from the examples he found, that in the early modern period with the rise of the nation state and European expansion ‘cartography was primarily a form of political discourse concerned with the acquisition and maintenance of power’ ( Imago Mundi 1988, 40 pp. 57-76). One might say the same of archives and libraries which spent (and do spend) their time ordering knowledge in the shape of books and manuscripts. In the case of a National Archives there is a clear explicit connection between the state and the archive; but even here within the archive and within the map there are other human elements at work as well, even subversive at least when it comes to interpreting them. -

Loyola University New Orleans Study Abroad

For further information contact: University of East London International Office Tel: +44 (0)20 8223 3333 Email: [email protected] Visit: uel.ac.uk/international Docklands Campus University Way London E16 2RD uel.ac.uk/international Study Abroad uel.ac.uk/international Contents Page 1 Contents Page 2 – 3 Welcome Page 4 – 5 Life in London Page 6 – 9 Docklands Campus Page 10 – 11 Docklands Page 12 – 15 Stratford Campus Page 16 – 17 Stratford Page 18 – 19 London Map Page 20 – 21 Life at UEL Page 23 Study Abroad Options Page 25 – 27 Academic School Profiles Page 28 – 29 Practicalities Page 30 – 31 Accommodation Page 32 Module Choices ©2011 University of East London Welcome This is an exciting time for UEL, and especially for our students. With 2012 on the horizon there is an unprecedented buzz about East London. Alongside a major regeneration programme for the region, UEL has also been transformed. Our £170 million campus development programme has brought a range of new facilities, from 24/7 multimedia libraries and state-of-the-art clinics,to purpose-built student accommodation and, for 2011, a major new sports complex. That is why I am passionate about our potential to deliver outstanding opportunities to all of our students. Opportunities for learning, for achieving, and for building the basis for your future career success. With our unique location, our record of excellence in teaching and research, the dynamism and diversity provided by our multinational student community and our outstanding graduate employment record, UEL is a university with energy and vision. I hope you’ll like what you see in this guide and that you will want to become part of our thriving community. -

Print West Indian Seamen Education Pack E7arts Celebrates the Launch of Its Monthly by Sukdev Sandhu

BLACK HISTORY Hackney, Newham and 2005 Tower Hamlets October MONTH What’s inside... Welcome Key: Arts and Heritage 06 Black History Month is celebrated every October across the UK. Its aims include promoting H Hackney knowledge of Black History and experience, providing information on positive Black contributions Children 12 to British Society and heightening awareness of Black cultural heritage. N Newham Family 16 For the first time this year, the three East London Boroughs of Hackney, Newham and T Tower Hamlets Tower Hamlets have joined together for Black History Month in a partnership collectively titled Film 22 Fusion East. We are proud to bring you the East London Black History Month programme. Literature and Spoken Word 24 In presenting the 2005 East London Black History Month programme we hope that you will be impressed, as we are, by the range of talent, experience and interests of the artists, arts Music and Dance 28 organisations, local groups and individuals participating in this year's Black History Month. The programme presents an exciting series of events including exhibitions, discussions, creative Politics and History 32 workshops, a quiz night, cricket coaching sessions and much more besides. Youth 34 We warmly invite residents from all communities and of all ages to take part in East London's Black History Month; to learn from and be entertained by the artists, musicians, scholars and Venues 36 many others featuring on the programme. From the three boroughs and Fusion East we hope you enjoy being part of this significant tri- borough partnership for East London Black History Month. -

Kingsley Hall and the Lester Archive (Available to the Public at Bishopsgate Library )

Kingsley Hall and the Lester Archive (available to the public at Bishopsgate Library https://www.bishopsgate.org.uk/content.aspx?CategoryID=1750 ) 1. Muriel Lester (1883-1968) Muriel and her sister Doris moved to Bow in 1908. From the late 1920s onwards, while Doris held the fort in Bow and later Dagenham, Muriel spent most of her time abroad, campaigning for peace as Travelling Secretary for the International Fellowship of Reconciliation. 2. Muriel and Doris Lester in Retirement For the last years of their lives the sisters lived in Loughton. Their home on the edge of Epping Forest, which they called Kingsley Cottage, has a local blue plaque commemorating the sisters. 3. Kingsley Lester 1877-1914 Kingsley was Muriel and Doris’s younger brother. He moved to Bow to join his sisters in their work but died in Muriel’s arms in1914 after an operation. With financial help from their father, the sisters bought a disused chapel as a base for their activities. It was named Kingsley Hall as a memorial to him. 4. Brick-laying Ceremony at the New Kingsley Hall, July 14th, 1927 As Kingsley Hall’s work expanded, funds were raised for new buildings. The present Kingsley Hall building and Children’s House nursery school (1923) were designed by Charles Cowles-Voysey, as was the nursery school at Kingsley Hall Dagenham. In the ceremony shown here, bricks were laid by famous supporters to represent the ideals of Kingsley Hall. Here, novelist John Galsworthy is laying the brick of Literature and actress Sybil Thorndike the brick of Drama. -

Key to London Map of Days

A London Map of Days This is the key to the daily details that feature on my etching A London Map of Days. I posted these every day on both Facebook and Twitter from the 9 February 2015 through to 8 February 2016. As the project continued, I began to enjoy myself and treat it more like a blog and so there is a marked difference between the amount of detail I have included at the beginning and the end of that year. 1 January 1660 Samuel Pepys begins writing his famous diary. He started the diary when he was only 26 years old and kept it for 10 years. He was a naval administrator and even though he had no maritime experience, he rose by a combination of hard work, patronage and talent for administration to be the Chief Secretary to the Admiralty under King Charles II and King James II. His diary, which was not published until the 19th century was written in a cryptic, personal shorthand and the first person to fully transcribe it, did so without the benefit of the key. It was not until 1970 that an unabridged version was published as previous editions had omitted passages deemed too obscene to print, usually involving Pepys sexual exploits. The diary combines personal anecdotes (often centred around drinking) with eyewitness accounts of great events such as the Great Plague of London, the Second Dutch War and the Great Fire of London. It is a glorious work and was a constant source of inspiration for my map. Daily detail from A London Map of Days. -

Robin Hood Gardens Blackwall Reach

Robin Hood Gardens Blackwall Reach The search for a sense of place A report by Graham Stewart WILD ReSEARCH Table of contents About the Author and Wild ReSearch 2 Preface 3 The Smithsons’ vision 4 The Place 7 Bring on the Brutalists 10 Streets in the Sky 12 A Home and a Castle? 14 What Went Wrong? 15 Renovation or Demolition? 16 Redeveloping Blackwall Reach 19 Urban Connections 20 References 24 The search for a sense of place 1 About the Author About Wild ReSearch Graham Stewart is Associate Director of Wild ReSearch and Wild ReSearch is the thought leadership and advisory division a noted historian of twentieth-century British politics, society of Wild Search, a boutique executive search business. We and the media. A former leader writer and columnist for The specialise in working with charities, educational organisations, Times, his is the newspaper’s official historian and author of The housing providers, arts, organisations and trade bodies and Murdoch Years. His other publications include the internationally rural organisations. Wild ReSearch provides research, analysis acclaimed Burying Caesar: Churchill, Chamberlain and the and project management for clients wishing to commission Battle for the Tory Party and he has also been a nominee for their own reports, in addition to organising events to launch the Orwell Prize, Britain’s most prestigious award for political such publications. writing. His sixth book, a study of British politics, culture and Our first publication, by Edward Wild and Neil Carmichael society in the 1980s will be published in January 2013. MP, was entitled ‘Who Governs the Governors? School A graduate of St Andrews University and with a PhD from governance in the Twenty-First Century. -

London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Notice of Meeting THE

London Borough of Barking and Dagenham Notice of Meeting THE EXECUTIVE Tuesday, 28 May 2002 - Civic Centre, Dagenham, 7:00 pm Members: Councillor C J Fairbrass (Chair); Councillor C Geddes (Deputy Chair); Councillor J L Alexander, Councillor S Kallar, Councillor M E McKenzie, Councillor B M Osborn, Councillor J W Porter and Councillor T G W Wade. Declaration of Members Interest: In accordance with Article 1, Paragraph 12 of the Constitution, Members are asked to declare any direct/indirect financial or other interest they may have in any matter which is to be considered at this meeting 22.5.02 Graham Farrant Chief Executive Contact Officer Steve Foster / Barry Ray Tel. 020 8227 2113 / 2134 Fax: 020 8227 2171 Minicom: 020 8227 2685 e-mail: [email protected] AGENDA 1. Apologies for Absence 2. Minutes - To confirm as correct the minutes of the meeting held on 14 May 2002 (Pages 1 - 16) Business Items Public Items 3 and Private Item 15 are business items. The Chair will move that these be agreed without discussion, unless any Member asks to raise a specific point. Any discussion of a Private Business Item will take place after the exclusion of the public and press. 3. Attendance at Chartered Institute of Housing Conference (Pages 17 - 18) Discussion Items 4. Annual Report of the Director of Public Health: Presentation (Report to follow on 24 May 2002) BR/04/03/02 5. Draft Race Equality Scheme (Pages 19 - 108) 6. Best Value Review of Waste Management: Final Report (Pages 109 - 162) 7. Best Value Review of the Library Service: Final Report (Pages 163 - 266) 8. -

Crossrail Assessment of Archaeology Impacts, Technical Report

CROSSRAIL ASSESSMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY IMPACTS, TECHNICAL REPORT. PART 2 OF 6, CENTRAL SECTION 1E0318-C1E00-00001 Cross London Rail Links Limited 1, Butler Place LONDON SW1H 0PT Tel: 020 7941 7600 Fax: 020 7941 7703 www.crossrail.co.uk CROSSRAIL ASSESSMENT OF ARCHAEOLOGY IMPACTS TECHNICAL REPORT PART 2 OF 6, CENTRAL SECTION: WESTBOURNE PARK TO STRATFORD AND ISLE OF DOGS FEBRUARY 2005 Project Manager: George Dennis Project Officer: Nicholas J Elsden Authors: Jon Chandler, Robert Cowie, James Drummond-Murray, Isca Howell, Pat Miller, Kieron Tyler, and Robin Wroe-Brown Museum of London Archaeology Service © Museum of London Mortimer Wheeler House, 46 Eagle Wharf Road, London N1 7ED tel 0207 410 2200 fax 0207 410 2201 email [email protected] Archaeology Service 17/02/2005 Crossrail Archaeological Impact Assessment: Central Route Section © MoLAS List of Contents Introduction 1 Route overview 2 Zone A: Royal Oak to Hatton Garden 2 Boundaries and layout 2 Topography and geology 2 Archaeological and historical background 3 Selected research themes 7 Zone B: Hatton Garden to Wilkes Street 9 Boundaries and layout 9 Topography and Geology 9 Archaeological and historical background 9 Selected research themes 14 Zone C: Wilkes Street to West India Dock North and Lea Valley 16 Boundaries and layout 16 Topography and Geology 16 Archaeological and Historical Background 16 Selected Research Themes 19 Zone D: West India Dock to Dartford Tunnel 20 Boundaries and layout 20 Topography and Geology 20 Archaeological and historical background 20 Selected research -

An Early Eighteenth-Century Cartographic Record of an Oxfordshire Manor

An Early Eighteenth-Century Cartographic Record of an Oxfordshire Manor By W lLLlAM R.A VENHILL OEL GASCOYNE, a pioneer of large-scale county mapping and a notable estate surveyor,' compiled in 1701 A Scheme of the Manor of GREAT HASELET and JLA TCHFORD in the Parish of Haseley in the Counry of Oxford.' In its present form this estate map covers three pieces ofvcllum stuck and stitched together so as to make up a continuous sheet which measures 131 ·5 cm. west to east and 78.5 cm. south to north. It gives the impression of having been well-used, for the vellum is stained in places, much of the lettering has been rubbed off, while the colours, by their lack of freshness, bear witness to the friction of handling over the centuries. Nevertheless, for a flat map which was housed on the manor from 1701 to the 1930S it is remarkably well-preserved and provides an interesting survi,·ing example of Joel Gascoyne's work. The circumstances which brought him to Oxfordshire are of interest, and once again demonstrate the importance to the study of cartography of the interplay of personalities at a national and local level. Much of the surveying career of Joel Gascoyne is already known and so it is necessary to outline only the main events in his life in order that this episode can be given its appropriate place.) Joel Gascoyne was born in Kingston-upon-Hull, in 1650, the son of Thomas Gaskin (Gascoyne) a sailor.. In 1668, Joel Gascoyne was apprenticed to John Thornton, citizen and draper of London, from whom he acquired the skills of chart making and surveying.s In 1675, Joel Gascoyne set himself up in business on Thames-side as a chart-maker,6 but after [689 he practised mainly as an estate and land surveyor. -

For People Who Love Early Maps Early Love Who People for 136 No

136 THE IntErnational Map CollEctors’ SociETY spring 2014 No.136 FOR PEOPLE WHO LOVE EARLY MAPS JOURNAL ADVERTISING Index of Advertisers 4 issues per year Colour B&W Altea Gallery 63 Full page (same copy) £950 £680 Half page (same copy) £630 £450 Antiquariaat Sanderus 51 Quarter page (same copy) £365 £270 Barry Lawrence Ruderman 40 For a single issue Full page £380 £275 Clive A Burden 2 Half page £255 £185 Christie’s 29 Quarter page £150 £110 Flyer insert (A5 double-sided) £325 £300 Dominic Winter 51 Frame 63 Advertisement formats for print Gonzalo Fernández Pontes 58 We can accept advertisements as print ready artwork saved as tiff, high quality jpegs or pdf files. Graham Franks 63 It is important to be aware that artwork and files that Jonathan Potter 21 have been prepared for the web are not of sufficient quality for print. Full artwork specifications are Kenneth Nebenzahl Inc. 57 available on request. Kunstantiquariat Monika Schmidt 52 Kunstantikvariat Pama AS 39 Advertisement sizes Librairie Le Bail 58 Please note recommended image dimensions below: Full page advertisements should be 216mm high x Loeb-Larocque 45 158mm wide and 300-400 ppi at this size. The Map House inside front cover Half page advertisements are landscape and 105mm high x 158mm wide and 300-400 ppi at this size. Martayan Lan outside back cover Quarter page advertisements are portrait and are Mostly Maps 20 105mm high x 76mm wide and 300-400 ppi at this size. Murray Hudson 52 The Observatory 58 IMCoS Website Web Banner £160* The Old Print Shop Inc. -

An Account of the Ancient Town of Frodsham In

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com Harvard College Library ) ACADEMIAE SIGILLUM RO INV.NO FROM THE GIFT OF WILLIAM ENDICOTT , JR . ( Class of 1887 ) OF BOSTON هت AN ACCOUNT OF THE ANCIENT TOWN OF FRODSHAM , IN CHESHIRE . All only for to publish plaine Tyme past , tyme present , bothe , That tyme to come may well retaine Of each good tyme the truthe . BY WILLIAM BEAMONT . WARRINGTON : PERCIVAL PEARSE , 8 , SANKEY STREET . I 88 1 . Pr 5184.68 HARVARD COLLEGE JUN 14 1918 LIBRARY biti Price ca pe eman TO THE Reverend Henry Birdwood Blogg , M.A. , VICAR OF FRODSHAM ( The 42nd in succession to that office ) , WHO , WHILE FAITHFULLY DISCHARGING HIS SPIRITUAL DUTIES , SUGGESTED , AND BY THE LIBERAL CONTRIBUTIONS OF HIS PARISHIONERS AND OTHERS , CARRIED OUT THE DESIGN OF RESTORING THE ORIGINAL FEATURES WHICH HIS VENERABLE PARISH CHURCH HAD RECEIVED FROM ITS FOUNDER IN THE NINTH CENTURY , BUT WHICH TIME AND INJUDICIOUS REPAIRS HAD GREATLY OBSCURED , THIS BOOK IS RESPECTFULLY DEDICATED BY Its Author . Orford Hall , September 19th , 1881 . FRODSHAM : SOME ACCOUNT OF ITS HISTORY . CHAPTER I. BEFORE THE NORMAN CONQUEST . FRODSHAM , though a very ancient market town , with a weekly 1 market and two fairs yearly , and once an important pass defending the entrance into Cheshire from the west , has lost , or perhaps more properly may be said to have gained , by the change to more peaceful times , some of its former importance .