The Thames Gateway: an Introduction to the Historical Landscapes of the Northern Riverside

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Greater London Authority

Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London March 2009 Consumer Expenditure and Comparison Goods Retail Floorspace Need in London A report by Experian for the Greater London Authority March 2009 copyright Greater London Authority March 2009 Published by Greater London Authority City Hall The Queen’s Walk London SE1 2AA www.london.gov.uk enquiries 020 7983 4100 minicom 020 7983 4458 ISBN 978 1 84781 227 8 This publication is printed on recycled paper Experian - Business Strategies Cardinal Place 6th Floor 80 Victoria Street London SW1E 5JL T: +44 (0) 207 746 8255 F: +44 (0) 207 746 8277 This project was funded by the Greater London Authority and the London Development Agency. The views expressed in this report are those of Experian Business Strategies and do not necessarily represent those of the Greater London Authority or the London Development Agency. 1 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY.................................................................................................... 5 BACKGROUND ........................................................................................................................... 5 CONSUMER EXPENDITURE PROJECTIONS .................................................................................... 6 CURRENT COMPARISON FLOORSPACE PROVISION ....................................................................... 9 RETAIL CENTRE TURNOVER........................................................................................................ 9 COMPARISON GOODS FLOORSPACE REQUIREMENTS -

Making a Home in Silvertown – Transcript

Making a Home in Silvertown – Transcript PART 1 Hello everyone, and welcome to ‘Making a Home in Silvertown’, a guided walk in association with Newham Heritage Festival and the Access and Engagement team at Birkbeck, University of London. My name’s Matt, and I’m your tour guide for this sequence of three videos that lead you on a historic guided walk around Silvertown, one of East London’s most dynamic neighbourhoods. Silvertown is part of London’s Docklands, in the London Borough of Newham. The area’s history has been shaped by the River Thames, the Docks, and the unrivalled variety of shipping, cargoes and travellers that passed through the Port of London. The walk focuses on the many people from around the country and around the world who have made their homes here, and how residents have coped with the sometimes challenging conditions in the area. It will include plenty of historical images from Newham’s archives. There’s always more to explore about this unique part of London, and I hope these videos inspire you to explore further. The reason why this walk is online, instead of me leading you around Silvertown in person, is that as we record this, the U.K. has some restrictions on movement and public assembly due to the pandemic of COVID-19, or Coronavirus. So the idea is that you can download these videos onto a device and follow their route around the area, pausing them where necessary. The videos are intended to be modular, each beginning and ending at one of the local Docklands Light Railway stations. -

Reading History in Early Modern England

READING HISTORY IN EARLY MODERN ENGLAND D. R. WOOLF published by the press syndicate of the university of cambridge The Pitt Building, Trumpington Street, Cambridge, United Kingdom cambridge university press The Edinburgh Building, Cambridge CB2 2RU, UK www.cup.cam.ac.uk 40 West 20th Street, New York, NY 10011–4211, USA www.cup.org 10 Stamford Road, Oakleigh, Melbourne 3166, Australia Ruiz de Alarco´n 13, 28014 Madrid, Spain © Cambridge University Press 2000 This book is in copyright. Subject to statutory exception and to the provisions of relevant collective licensing agreements, no reproduction of any part may take place without the written permission of Cambridge University Press. First published 2000 Printed in the United Kingdom at the University Press, Cambridge Typeset in Sabon 10/12pt [vn] A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Library of Congress Cataloguing in Publication data Woolf, D. R. (Daniel R.) Reading History in early modern England / by D. R. Woolf. p. cm. (Cambridge studies in early modern British history) ISBN 0 521 78046 2 (hardback) 1. Great Britain – Historiography. 2. Great Britain – History – Tudors, 1485–1603 – Historiography. 3. Great Britain – History – Stuarts, 1603–1714 – Historiography. 4. Historiography – Great Britain – History – 16th century. 5. Historiography – Great Britain – History – 17th century. 6. Books and reading – England – History – 16th century. 7. Books and reading – England – History – 17th century. 8. History publishing – Great Britain – History. I. Title. II. Series. DA1.W665 2000 941'.007'2 – dc21 00-023593 ISBN 0 521 78046 2 hardback CONTENTS List of illustrations page vii Preface xi List of abbreviations and note on the text xv Introduction 1 1 The death of the chronicle 11 2 The contexts and purposes of history reading 79 3 The ownership of historical works 132 4 Borrowing and lending 168 5 Clio unbound and bound 203 6 Marketing history 255 7 Conclusion 318 Appendix A A bookseller’s inventory in history books, ca. -

Public Health Ward Profile: East Tilbury

East Tilbury Ward (E05002234) Published by Thurrock Public Health 2017/18 Population Pyramid East Tilbury Ward has a greater percentage of adults aged 50- 69yrs compared to Thurrock. Conversely there is a smaller proportion of 30-39yr olds. Source: ONS Mid-Year Estimates 2017 East Tilbury Ward (E05002234) Published by Thurrock Public Health 2017/18 Ethnicity Groups (%) Deprivation White/White East Tilbury is ranked 11th 95% British/White Other out of the 20 Thurrock wards 1 = Most Deprived Black/African/Caribbean/ 3% 20 = Least Deprived Black British Unemployment Deprivation Poverty Asian/Asian British 1% Social Mixed/Multiple 1% Ethnic Groups Other Ethnic Group 0% Deprivation is strongly associated with poor physical and mental health 0 20 40 60 80 100 Source: DCLG (Department of Percentage (%) Communities and Local Government) Employment Thurrock East Tilbury Ward (%) Average (%) Employee: Full-time 44.8 42.3 Employee: Part-time 16.4 14.5 Self-employed 8.1 9.0 Being in employment has been shown to be Unemployed 4.4 5.2 highly protective to one's health. Retired 10.9 12.2 Conversely evidence Looking after home or family 5.3 5.1 shows that being unemployed is linked to Long-term sick or disabled 2.8 3.4 poor physical and mental health Student (inc. full-time students) 3.6 3.5 outcomes. (Source for all data in this profile is Census 2011 unless otherwise stated) East Tilbury Ward (E05002234) Published by Thurrock Public Health 2017/18 Primary Schools (No Secondary Schools within this Ward) SATs Results 2017 East Tilbury Primary School 75 67% and Nursery 60 Approx pupils - 673 45 Ofsted rating - Good 30 15 Percentage (%) Percentage 0 East Tilbury Primary School and Nursery % Pupils Meeting Expected Standard England Average (63%) Government pupil progress scores, comprised of key stage 1 assessments & key stage 2 tests, compared to pupils across England. -

Template Letter

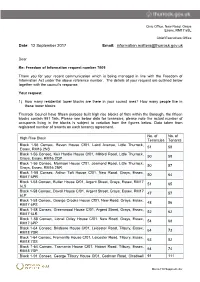

Civic Office, New Road, Grays Essex, RM17 6SL Chief Executives Office Date: 12 September 2017 Email: [email protected] Dear Re: Freedom of Information request number 7005 Thank you for your recent communication which is being managed in line with the Freedom of Information Act under the above reference number. The details of your request are outlined below together with the council’s response. Your request 1) How many residential tower blocks are there in your council area? How many people live in these tower blocks Thurrock Council have fifteen purpose built high rise blocks of flats within the Borough, the fifteen blocks contain 981 flats. Please see below data for tenancies, please note the actual number of occupants living in the blocks is subject to variation from the figures below. Data taken from registered number of tenants on each tenancy agreement. No. of No. of High Rise Block Tenancies Tenants Block 1-56 Consec, Bevan House Cf01, Laird Avenue, Little Thurrock, 51 58 Essex, RM16 2NS Block 1-56 Consec, Keir Hardie House Cf01, Milford Road, Little Thurrock, 50 58 Grays, Essex, RM16 2QP Block 1-56 Consec, Morrison House Cf01, Jesmond Road, Little Thurrock, 50 57 Grays, Essex, RM16 2NR Block 1-58 Consec, Arthur Toft House Cf01, New Road, Grays, Essex, 50 64 RM17 6PR Block 1-58 Consec, Butler House Cf01, Argent Street, Grays, Essex, RM17 51 65 6LS Block 1-58 Consec, Davall House Cf01, Argent Street, Grays, Essex, RM17 47 57 6LP Block 1-58 Consec, George Crooks House Cf01, New Road, Grays, Essex, 48 56 RM17 6PS -

A Unique Experience with Albion Journeys

2020 Departures 2020 Departures A unique experience with Albion Journeys The Tudors & Stuarts in London Fenton House 4 to 11 May, 2020 - 8 Day Itinerary Sutton House $6,836 (AUD) per person double occupancy Eastbury Manor House The Charterhouse St Paul’s Cathedral London’s skyline today is characterised by modern high-rise Covent Garden Tower of London Banqueting House Westminster Abbey The Globe Theatre towers, but look hard and you can still see traces of its early Chelsea Physic Garden Syon Park history. The Tudor and Stuart monarchs collectively ruled Britain for over 200 years and this time was highly influential Ham House on the city’s architecture. We discover Sir Christopher Wren’s rebuilding of the city’s churches after the Great Fire of London along with visiting magnificent St Paul’s Cathedral. We also travel to the capital’s outskirts to find impressive Tudor houses waiting to be rediscovered. Kent Castles & Coasts 5 to 13 May, 2020 - 9 Day Itinerary $6,836 (AUD) per person double occupancy The romantic county of Kent offers a multitude of historic Windsor Castle LONDON Leeds Castle Margate treasures, from enchanting castles and stately homes to Down House imaginative gardens and delightful coastal towns. On this Chartwell Sandwich captivating break we learn about Kent’s role in shaping Hever Castle Canterbury Ightham Mote Godinton House English history, and discover some of its famous residents Sissinghurst Castle Garden such as Ann Boleyn, Charles Dickens and Winston Churchill. In Bodiam Castle a county famed for its castles, we also explore historic Hever and impressive Leeds Castle. -

At Barking Riverside

PARKLANDS 1–3 BEDROOM APARTMENTS 3–4 BEDROOM HOUSES BARKING RIVERSIDE WILL DELIVER 10,800 HOMES AND 65,000 SQ. M. OF COMMERCIAL SPACE OVER 178 HECTARES Computer generated image. BARKINGRIVERSIDE.LONDON #AGIANTLEAPFORLONDON 1 2KM OF SOUTH-FACING RIVER THAMES FRONTAGE Computer generated image. 2 BARKINGRIVERSIDE.LONDON #AGIANTLEAPFORLONDON 3 WELCOME TO PARKLANDS AT BARKING RIVERSIDE. A brand new neighbourhood for Parklands, the first phase of new London, Barking Riverside is a vibrant homes to launch on site with L&Q, COME HOME new district, sitting alongside 2km of is a collection of one to four bedroom majestic River Thames frontage. contemporary houses and apartments. Once completed, the pioneering Each home will bring together a perfect TO A BRAND NEW development will offer 10,800 new blend of comfort, architecture, design homes, alongside shops, restaurants and impeccable eco-credentials, where and leisure and sports facilities. There you can live the life you want to live, will be public parks and river walkways, and live it in style. ADVENTURE excellent new schools with state-of- the-art facilities, and a new London Overground station, all in close proximity of central London. 4 BARKINGRIVERSIDE.LONDON #AGIANTLEAPFORLONDON 5 A VIBRANT COMMUNITY Be part of a brand new, thriving community at Barking Riverside. Set to be one of the most dynamic new destinations in the capital, once completed, Barking Riverside’s District Centre will include an impressive 65,000 square metres of commercial floorspace – home to shopping outlets, restaurants, bars and cafés. A growing number of businesses are already making their mark on the East London development. -

History of the Welles Family in England

HISTORY OFHE T WELLES F AMILY IN E NGLAND; WITH T HEIR DERIVATION IN THIS COUNTRY FROM GOVERNOR THOMAS WELLES, OF CONNECTICUT. By A LBERT WELLES, PRESIDENT O P THE AMERICAN COLLEGE OP HERALDRY AND GENBALOGICAL REGISTRY OP NEW YORK. (ASSISTED B Y H. H. CLEMENTS, ESQ.) BJHttl)n a account of tljt Wu\\t% JFamtlg fn fHassssacIjusrtta, By H ENRY WINTHROP SARGENT, OP B OSTON. BOSTON: P RESS OF JOHN WILSON AND SON. 1874. II )2 < 7-'/ < INTRODUCTION. ^/^Sn i Chronology, so in Genealogy there are certain landmarks. Thus,n i France, to trace back to Charlemagne is the desideratum ; in England, to the Norman Con quest; and in the New England States, to the Puri tans, or first settlement of the country. The origin of but few nations or individuals can be precisely traced or ascertained. " The lapse of ages is inces santly thickening the veil which is spread over remote objects and events. The light becomes fainter as we proceed, the objects more obscure and uncertain, until Time at length spreads her sable mantle over them, and we behold them no more." Its i stated, among the librarians and officers of historical institutions in the Eastern States, that not two per cent of the inquirers succeed in establishing the connection between their ancestors here and the family abroad. Most of the emigrants 2 I NTROD UCTION. fled f rom religious persecution, and, instead of pro mulgating their derivation or history, rather sup pressed all knowledge of it, so that their descendants had no direct traditions. On this account it be comes almost necessary to give the descendants separately of each of the original emigrants to this country, with a general account of the family abroad, as far as it can be learned from history, without trusting too much to tradition, which however is often the only source of information on these matters. -

![(Essex.] East Ham. 80 Post Office](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5536/essex-east-ham-80-post-office-445536.webp)

(Essex.] East Ham. 80 Post Office

' (ESSEX.] EAST HAM. 80 POST OFFICE Surrogate for granting Licences of Marriage• ~for Baptut Chapel, North Rtreet ; Rev. W m .elements, ministr proving Wills, Rev. Charles Burney, M.A. Vicarage Baptist (Particular) Chapel, High st.; ministers various PuBLIC ScHooLs :- Independent Chapel, Parson's lane; Rev. John Reynolds, Free Grammar, High street; James Flavell, master miniQter; Rev. Joseph Waite, assistant minister St. Andrew'1 National, High street; John Bryon, Independent Chapel, Higb st.; Rev.Benj.Johnson,ministr master; Miss Mary Ann Earthy, mistress Friends' Meeting House, Colchester road National, Greenstead green; John Isaac, master; Miss PosTING HousEs:- Elizabeth Evens, mistress ' George,' Charles Nunn, Market bill Trinity National, Chapel street; Frederick M nrton, 'White Hart,' William Moye, High street master; Mrs. Emma Murton, mistress 'Bull,' John Elsdon, Bridue street Br-itish, Clipt hedges; William Stratton, master; Miss CoAcH TO BRAINTREE STATION.-The Eagle, evPry Elizabeth Freeman, mistress mornin~r & afternoon, sunday excepted, from the' White Infant, Clipt hedges; Miss Sarah Grey, mistress Hart,' Hi~h street PLACES OP WORSHIP:- CARRIERS TO:- St. ilndrew's Church, High street; Rev. Charles Burney, LONDON-William Howard's waggon, from Brid!le foot, M.A. vic11r; Rev. Fredk. Henry Gray,:s.A.. curate; Rev. to the 'Bull,' Aldgate, monday, tue:,day, thursday & friday Robert Helme, B.A. assistant curate COLCHESTER-Francis Mansfield, from his honsP, Trinity Holy Trinity Church, Chapel street; Rev. Duncan Fraser, street, tuesday, thursday & saturday; returns same days M.A. incumbent; Rev. Charles Cobb, l'tl.A.. curate BRAINTREE-Henry Cresswell, every day, & through to St. James's Church, Greenstead green; Rev. William London on friday Billopp, M.A. -

PRIVATE RESIDENTS. Bll 741 Lledbam .A.Rtbur, 1 South Primrose Bentley Charles

ESSEX.) PRIVATE RESIDENTS. BlL 741 lleDbam .A.rtbur, 1 South Primrose Bentley Charles. Harry, The Chateau, Best Arthur Edward, 40 Moruington hill. Chelmsford Cliff Sea gro.West cliff,Leigh-on-Sea road, Chingford Jlenham C.E.28Wellesley rd.Colchestr Bentley Charles S. 6 Sewardstone rd. Best Geo. A. 553 Leigh rd.ea.Southnd Jlenbam Leonard A. Burleigh, Third Waltham Abbey Best Henry, The Haven, Cliff Sea avenue. Frinton-on-Sea Bentley Frederick Joseph, 12 Seward grove, West cliff, Leigh-on-Sea Jlenbam Mrs. 36 Crouch st.Colchester stone road, Waltham Abbey Best Miss, 10 Prittlewell sq. Southend Jlenbam William Gurney, 9 Lexden Bentley Harry, Sea View house, Great Best Mrs. 589 Leigh rd. ea. Southend 10ad, Colchester Wakering, Shoeburyness Bestall Rev. W. J. Gregory, Wesley Jlenjamin Isaac, 127 Elm rd. Leigh Bentley John, Aberdour, Hockley house, Palmer's avenue, Grays Jlenn Rev. Herbert, uo Coggeshall Bentley John, 3 Satanita road, West Bestley Wait. F. Crays hill, Billericay road, Braintree cliff, Southend Beswick Henry, Heilbron, Parkstone JJennett Col. Alfd. Chas. D.S.O. ..A.rd- Bentley John Thomas, 4 Milton viis. avenue, Hornchurch, Romford leigh park, ..A.rdleigh, Colchester Dovercourt, Harwich Bethell Thomas Robert J.P. The Firs,. Jlennett Rev. Henry, 120 Wellesley Bentley Louis, Glenholme, Park rd. Woodford. NE road, Clacton-on-Sea Shenfield, Brentwood Bethney Chas.2r Ambleside drv.Sthnd Bennett A. E. The Oaks,Vange,Pitsea Bentley Miss,39Sun st.WalthamAbbey Bethune Miss, 4 Stanhope gardens, Jlennett Albt.C.3r Roman rd.Colchstr Bentley Mrs. 5 Palmeira avenue, The Avenue, Loug'hton Jlennett Arnold, Comarques, Thorpe- West cliff, Southend Betterton H.B. -

London and South East

London and South East nationaltrust.org.uk/groups 69 Previous page: Polesden Lacey, Surrey Pictured, this page: Ham House and Garden, Surrey; Basildon Park, Berkshire; kitchen circa 1905 at Polesden Lacey Opposite page: Chartwell, Kent; Petworth House and Park, West Sussex; Osterley Park and House, London From London living at New for 2017 Perfect for groups Top three tours Ham House on the banks Knole Polesden Lacey The Petworth experience of the River Thames Much has changed at Knole with One of the National Trust’s jewels Petworth House see page 108 to sweeping classical the opening of the new Brewhouse in the South East, Polesden Lacey has landscapes at Stowe, Café and shop, a restored formal gardens and an Edwardian rose Gatehouse Tower and the new garden. Formerly a walled kitchen elegant decay at Knole Conservation Studio. Some garden, its soft pastel-coloured roses The Churchills at Chartwell Nymans and Churchill at restored show rooms will reopen; are a particular highlight, and at their Chartwell see page 80 Chartwell – this region several others will be closed as the best in June. There are changing, themed restoration work continues. exhibits in the house throughout the year. offers year-round interest Your way from glorious gardens Polesden Lacey Nearby places to add to your visit are Basildon Park see page 75 to special walks. An intriguing story unfolds about Hatchlands Park and Box Hill. the life of Mrs Greville – her royal connections, her jet-set lifestyle and the lives of her servants who kept the Itinerary ideas house running like clockwork. -

Sandars Lectures 2007: Conversations with Maps

SANDARS LECTURES 2007: CONVERSATIONS WITH MAPS Sarah Tyacke CB Lecture III: There are maps and there are maps – motives, markets and users As Christian Jacob put it ‘There are maps and there are maps’. More prosaically the nature of them depends on what you want the map or chart for and how you the reader perceive it? This third lecture is about what drove the cartographic activity internally and externally and how did it manifest itself in England and the rest of maritime Europe through its distributors, patrons and readers. This is probably the most challenging subject, first articulated in embryonic form as part of the history of cartography’s remit in the 1970s by David Woodward (as we saw in lecture I) and developed thereafter as the history of cartography took a ‘second turn’ and embraced social context. This ‘second turn’ challenged the inevitability of progress in cartography and understood that cartography was just as much a product of its society as other texts. In the case of Brian Harley he took this further arguing powerfully, from the examples he found, that in the early modern period with the rise of the nation state and European expansion ‘cartography was primarily a form of political discourse concerned with the acquisition and maintenance of power’ ( Imago Mundi 1988, 40 pp. 57-76). One might say the same of archives and libraries which spent (and do spend) their time ordering knowledge in the shape of books and manuscripts. In the case of a National Archives there is a clear explicit connection between the state and the archive; but even here within the archive and within the map there are other human elements at work as well, even subversive at least when it comes to interpreting them.