The Virtuous Circle: Putting Korea’S Startup Ecosystem on a Path to Sustainable Long-Run Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

20Annual Report UNITED STATES SECURITIES and EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C

20 20Annual Report UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K È ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2020. OR ‘ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Transition Period from to . Commission file number 001-37713 eBay Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 77-0430924 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 2025 Hamilton Avenue San Jose, California 95125 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (408) 376-7008 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading symbol Name of exchange on which registered Common stock EBAY The Nasdaq Global Select Market 6.00% Notes due 2056 EBAYL The Nasdaq Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes È No ‘ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ‘ No È Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

E-Commerce in South Korea: a Canadian Perspective

E-COMMERCE IN SOUTH KOREA: A CANADIAN PERSPECTIVE REPORT PREPARED BY: Theresa Eriksson, Luleå University of Technology, Sweden Kristin Matheson, Luleå University of Technology, Sweden Dr. Leyland Pitt, Professor of Marketing, Beedie School of Business, Simon Fraser University Dr. Kirk Plangger, King’s College, London, UK Dr. Karen Robson, University of Windsor 1 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4 INTRODUCTION 5 SOUTH KOREA: THE COUNTRY, THE ECONOMY 7 METHODOLOGY 8 THE SOUTH-KOREAN E-COMMERCE CONTEXT 9 Customer Context 9 The E-commerce Shopping process 11 Products and Brands 15 Online Behaviour 16 Shopping Events and Timing 20 Main Stakeholders 24 Technology and Infrastructure Landscape 27 For Canadian Firms Contemplating E-commerce in South Korea: 32 Marketing Considerations FUTURE OUTLOOK 40 CONCLUSION 41 CASE STUDIES 42 Case Study I: Yogiyo 42 Case Study II: Pinkfong and Baby Shark 46 APPENDIX 53 Digital Technology in South Korea and Canada — A Comparison of Digital Device Ownership, Digital Media Consumption, and Digital Behaviour. ABOUT THE AUTHORS 68 3 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY This report focuses on e-commerce opportunities for Canadian firms in South Korea, one of the world’s most connected markets. Korea is not for the faint-hearted: consumers are very sophisticated and markets are very competitive. Nevertheless, for Canadian firms with excellent offerings and a willingness to provide excellent service, coupled with patience and an ability to build good relationships at all levels, Korea offers significant opportunities. The report proceeds as follows: First, it provides a broad overview of the nation of South Korea with particular focus on e-commerce and online connectivity in that country. -

Quarterly Portfolio Holdings

T. Rowe Price Extended Equity Market Index Fund PEXMX 06/30/2021 (Unaudited) Portfolio of Investments Investments in Securities Coupon % Maturity Shares/Par Value ($) % of Net Assets 10X Genomics 13,000 2,545,660 0.183% 1-800-Flowers.com 7,768 247,566 0.018% 1Life Healthcare 14,500 479,370 0.034% 1st Source 8,652 401,972 0.029% 22nd Century 46,800 216,684 0.016% 2U 13,500 562,545 0.040% 3D Systems 26,350 1,053,210 0.076% 8x8 19,600 544,096 0.039% AAON 6,690 418,727 0.030% Aaron s 7,567 242,068 0.017% Abercrombie & Fitch 14,500 673,235 0.048% ABM Industries 11,150 494,503 0.035% Abraxas Petroleum 15,382 49,684 0.004% Acadia Healthcare 16,900 1,060,475 0.076% ACADIA Pharmaceuticals 25,800 629,262 0.045% Acadia Realty Trust, REIT 16,650 365,634 0.026% Acceleron Pharma 9,500 1,192,155 0.086% Acco Brands 21,900 188,997 0.014% AcelRx Pharmaceuticals 95,700 132,066 0.009% ACI Worldwide 20,300 753,942 0.054% Aclaris Therapeutics 25,400 446,024 0.032% ACM Research 2,800 286,216 0.021% ACRES Commercial Realty, REIT 15,332 246,232 0.018% Acuity Brands 6,300 1,178,289 0.085% Acushnet Holdings 7,475 369,265 0.026% Adamas Pharmaceuticals 33,700 177,936 0.013% Adams Resources & Energy 3,341 92,512 0.007% AdaptHealth 12,200 334,402 0.024% Adaptive Biotechnologies 15,500 633,330 0.045% Addus HomeCare 2,300 200,652 0.014% Adient 18,000 813,600 0.058% ADT 29,300 316,147 0.023% Adtalem Global Education 12,200 434,808 0.031% Advanced Drainage Systems 8,791 1,024,767 0.074% Advanced Energy Industries 5,750 648,083 0.047% Adverum Biotechnologies 46,900 164,150 -

The Rise of Start-Ups Source List

The Rise Of Start-Ups Source List Top 25 Start-Ups https://www.investopedia.com/investing/10-biggest-start-ups-valuation-recode/ https://www.cbinsights.com/research-unicorn-companies Toutiao (Bytedance) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ByteDance https://pandaily.com/bytedance-rumored-to-hit-20-billion-revenue-goal-for-2019/ JUUL Labs https://news.crunchbase.com/news/juul-lands-12-8b-from-big-tobacco-as-vaping-grows-up-sells-out/ Nubank https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nubank https://techcrunch.com/2014/09/25/finance-startup-nubank-nabs-14-3m-in-sequoias-first-brazil-investment/ Stripe https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Stripe_(company) Airbnb https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Airbnb https://www.businessinsider.com.au/estimating-airbnbs-revenues-2012-3 https://www.businessinsider.com/how-airbnb-was-founded-a-visual-history-2016-2 https://www.reuters.com/article/us-airbnb-results/airbnb-had-substantially-more-than-1-billion-in-quarterly-revenue-idUSKCN1NL270 Kuaishou https://www.reuters.com/article/us-kuaishou-fundraising/chinas-kuaishou-in-1-billion-tencent-led-funding-round-eyes-ipo-sources-idUSKBN1FE11D Oyo Rooms https://www.businesstoday.in/top-story/oyo-hotel-sales-globally-jump-over-4-fold-to-usd-18-bn-in-2018/story/318233.html https://www.financialexpress.com/industry/even-as-revenue-soared-14x-to-rs-32-8-cr-oyo-rooms-posts-24x-jump-in-losses-in-fy16/785161/ Coupang https://techcrunch.com/2018/11/20/coupang-raises-2-billion-from-softbanks-vision-fund/ https://venturebeat.com/2012/05/30/koreas-21-month-old-e-commerce-startup-coupang-will-generate-600m-in-revenue-this-year/ -

International Ecommerce

A special report from the editors of International Ecommerce The challenges and opportunities in global e-retail PRESENTED BY: The growth opportunity of international ecommerce International shipping is complex. It can be costly to send products to customers in other countries, and it may also require retailers to clear hurdles they don’t normally face with domestic shipments. Because of these complexities, many retailers--especially small and midsized businesses--don’t bother to ship abroad, which limits their opportunities for growth. Some leading North American brands and retailers have seen those opportunities and expanded their international and cross-border operations in the past year. And many see global expansion as an important source of growth, according to a recent survey of 111 retailers and brands by Internet Retailer and the Global E-Commerce Leaders Forum, an organization dedicated to helping retailers and brands sell internationally via ecommerce. Nearly 48% of survey respondents reported 2017 growth in overseas web sales of at least 15% and 80% of respondents called international ecommerce “a critical source of our ecommerce growth in the future.” This e-book, brought to you by GlobalPost, presents articles and data previously published by Internet Retailer and helps to define these issues and uncover the opportunities. Reaching global online shoppers . .. 3 How retailers can overcome international shipping challenges and open up new markets . .. 8 The top hurdles to international ecommerce . 10 Building a marketing strategy for global ecommerce . 11 Case Study: Victoria’s Secret enters China ecommerce with a flourish . 19 Emerging legal trends in international ecommerce . 21 Copyright 2018-2019 Internet Retailer and DigitalCommerce360.com. -

Retail(Neutral/Maintain)

[Korea] January 25, 2021 Retail (Neutral/Maintain) Coupang: Putting doubts to rest Mirae Asset Daewoo Co., Ltd. Myoungjoo Kim [email protected] Minjeong Kyeong [email protected] Coupang IPO coming into view IPO looking increasingly likely Coupang has reportedly passed preliminary screening for listing on the US Nasdaq market. Media reports have suggested the company could be worth around US$25-40bn, which implies a P/S of 1.7-2.8x based on our 2021 estimates. Amazon traded at 3.95x P/S in 2003, the year it first turned a profit (2002-04 average of 2.8x). In 2021, Coupang should benefit from a steady increase in commission income along with falling parcel delivery rates (due to volume growth), potentially leading to meaningful improvement in profitability. Potential valuation levels should also be viewed in the context of the company’s expanding retail market share. E-commerce market Coupang driving e -commerce market re alignment realignment has begun Coupang has regained its parcel delivery business license. In 2021, we expect the company to expand its fulfillment services in order to: 1) strengthen the competitiveness of its platform categories; and 2) raise commission income. The company should gain share in the e-commerce market, backed by: 1) enhanced competitiveness in directly sourced merchandise (especially in fashion); and 2) GMV growth of its marketplace resulting from the expansion of fulfillment services. Coupang looks likely to expand its e-commerce market share to 15.7% (+2.4%p) in 2021 and 19.3% (+3.6%p) in 2022. Retail market share to expand Market leadership to expand beyond e -commerce to broader retail sector Furthermore, Coupang appears likely to expand its share of the broader retail market to 5.8% (+1.4%p) in 2021 and 7.8% (+2.0%p) in 2022. -

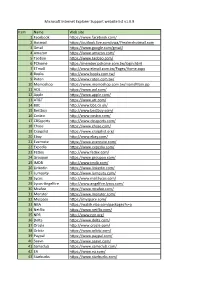

Item Name Web Site 1 Facebook

Microsoft Internet Explorer Support website list v1.0.9 Item Name Web site 1 Facebook https://www.facebook.com/ 2 Hotmail https://outlook.live.com/owa/?realm=hotmail.com 3 Gmail https://www.google.com/gmail/ 4 Amazon https://www.amazon.com/ 5 Taobao https://www.taobao.com/ 6 PChome https://member.pchome.com.tw/login.html 7 ETmall http://www.etmall.com.tw/Pages/Home.aspx 8 Books http://www.books.com.tw/ 9 Ruten http://www.ruten.com.tw/ 10 Momoshop https://www.momoshop.com.tw/main/Main.jsp 11 AOL https://www.aol.com/ 12 Apple https://www.apple.com/ 13 AT&T https://www.att.com/ 14 BBC http://www.bbc.co.uk/ 15 Bestbuy http://www.bestbuy.com/ 16 Costco http://www.costco.com/ 17 CBSsports http://www.cbssports.com/ 18 Chase https://www.chase.com/ 19 Craigslist https://www.craigslist.org/ 20 Ebay http://www.ebay.com/ 21 Evernote https://www.evernote.com/ 22 Expedia https://www.expedia.com/ 23 FEDex http://www.fedex.com/ 24 Groupon https://www.groupon.com/ 25 IMDB http://www.imdb.com/ 26 Linkedin https://www.linkedin.com/ 27 Lumosity https://www.lumosity.com/ 28 Lycos http://www.mail.lycos.com/ 29 Lycos-Angelfire http://www.angelfire.lycos.com/ 30 Mcafee https://www.mcafee.com/ 31 Monster https://www.monster.com/ 32 Myspace https://myspace.com/ 33 NBA https://watch.nba.com/packages?s=o 34 Netflix https://www.netflix.com/ 35 NPR http://www.npr.org/ 36 Delta https://www.delta.com/ 37 Oracle http://www.oracle.com/ 38 Orbitz https://www.orbitz.com/ 39 Paypal https://www.paypal.com/ 40 Saavn https://www.saavn.com/ 41 Samsclub https://www.samsclub.com/ -

ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT to SECTION 13 OR 15(D) of the SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT of 1934 for the Fiscal Year Ended December 31, 2019

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 Form 10-K ☒ ANNUAL REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the fiscal year ended December 31, 2019. OR ☐ TRANSITION REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 For the Transition Period from to . Commission file number 001-37713 eBay Inc. (Exact name of registrant as specified in its charter) Delaware 77-0430924 (State or other jurisdiction of (I.R.S. Employer incorporation or organization) Identification No.) 2025 Hamilton Avenue San Jose , California 95125 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip Code) Registrant’s telephone number, including area code: (408) 376-7008 Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(b) of the Act: Title of each class Trading symbol Name of exchange on which registered Common stock EBAY The Nasdaq Global Select Market 6.00% Notes due 2056 EBAYL The Nasdaq Global Select Market Securities registered pursuant to Section 12(g) of the Act: None Indicate by check mark if the registrant is a well-known seasoned issuer, as defined in Rule 405 of the Securities Act. Yes ☒ No ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is not required to file reports pursuant to Section 13 or Section 15(d) of the Act. Yes ☐ No ☒ Indicate by check mark whether the registrant (1) has filed all reports required to be filed by Section 13 or 15(d) of the Securities Exchange Act of 1934 during the preceding 12 months (or for such shorter period that the registrant was required to file such reports), and (2) has been subject to such filing requirements for the past 90 days. -

Baron Global Advantage Strategy

Baron Global Advantage Strategy March 31, 2021 Dear Investor: • Financials – the sector was up 11.4%, and we were 12.4% Performance underweight. • Industrials – the sector was up 7.5%, and we were 9.0% underweight. Baron Global Advantage Strategy declined 1.8% during the first quarter. The MSCI ACWI Index and the MSCI ACWI Growth Index, the Strategy’s Looking on a level deeper, within Consumer Discretionary our results were benchmarks, gained 4.6% and 0.3%, respectively, for the quarter. After a impacted by not being in the right sub-industries as we had no exposure to few years of very strong performance, including last year’s best absolute double-digit gainers such as hotels, casinos, and homebuilders, and instead and relative returns in the nine-year history of the Strategy, it was time for were significantly overweight e-commerce (internet & direct marketing many of our investments to take a breather. retail) and education services, sub-industries that were down 2.8% and 24.4%, respectively, during the quarter. Similarly, in IT, we had almost no Table I. exposure to the more cyclical sub-industries, such as communications Performance† equipment and semiconductors, which performed very well, and were Annualized for periods ended March 31, 2021 significantly overweight software and internet services & infrastructure which were either flat or down in the quarter. Baron Baron Global Global MSCI Advantage Advantage MSCI ACWI Ironically, the picture is similar from a geographical perspective, where we Strategy Strategy ACWI Growth seemed to have been in mostly the wrong places. Per usual, we were (net)1 (gross)1 Index1 Index1 overweight emerging markets, which underperformed and were responsible Three Months2 (1.80)% (1.60)% 4.57% 0.28% for about half of our underperformance. -

Netflix Growing Pains

NET 1YR Interestrates TREASURYS LAST PVS CHG WK MO QTR AGO Money&Markets e-Edition 3-month T-bill .04 .04 ... s t t .10 6-month T-bill .05 .05 ... s t r .11 52-wk T-bill .08 .08 ... s s r .12 4,480 S&P 500 35,080 Dow Jones industrials 2-year T-note .28 .30 -0.02 s s s .13 Close: 4,307.54 Close: 33,843.92 4,380 34,340 5-year T-note .98 1.01 -0.03 s s s .28 Change: -51.92 (-1.2%) Change: -546.8 (-1.6%) The yield on the 4,280 33,600 10-year T-note 1.52 1.54 -0.02 s s s .69 10 DAYS 10 DAYS 10-year Treasury 30-year T-bond 2.09 2.08 +0.01 s s s 1.46 4,600 36,000 note slid to 4,500 1.52% Thursday. 35,200 Yields affect 4,400 rates on mort- NAT'L WK 6MO 1YR 4,300 34,400 gages and other CONSUMER RATES AVG AGO AGO AGO 4,200 consumer loans. 33,600 48 month new car loan 3.72 t 3.73 3.89 4.05 4,100 r PRIME FED Money market account 0.07 0.07 0.08 0.10 4,000 32,800 ASMJ JA ASMJ JA RATE FUNDS 1 year CD 0.29 r 0.29 0.29 0.33 $30K Home equity loan 6.45 r 6.45 6.45 4.71 LAST 3.25 .13 6 MO AGO 3.25 .13 30 year fixed mortgage 3.18 s 3.03 3.03 3.26 HIGH LOW CLOSE CHG %CHG YTD Stocks Recap 1 YR AGO 3.25 .13 15 year fixed mortgage 2.46 s 2.29 2.32 2.51 DOW 34,557.37 33,833.32 33,843.92 -546.80 -1.59% +10.58% DOW Trans. -

MF Full Holdings

Hartford Growth Opportunities HLS Fund Full Portfolio Holdings* as of August 31, 2020 % of Security Coupon Maturity Shares/Par Market Value Net Assets Apple, Inc. 0.000 973,488 125,618,892 5.739 Amazon.com, Inc. 0.000 31,539 108,839,827 4.973 Microsoft Corp. 0.000 383,555 86,503,159 3.952 Facebook, Inc. 0.000 203,750 59,739,500 2.729 Alphabet, Inc. 0.000 36,224 59,028,095 2.697 Procter & Gamble Co. 0.000 368,050 50,912,357 2.326 salesforce.com, Inc. 0.000 159,562 43,504,579 1.988 NextEra Energy, Inc. 0.000 148,817 41,545,242 1.898 Mastercard, Inc. 0.000 115,716 41,448,314 1.894 JP Morgan Chase & Co. 0.000 407,707 40,848,164 1.866 UnitedHealth Group, Inc. 0.000 128,676 40,217,684 1.837 Eli Lilly and Co. 0.000 246,724 36,611,374 1.673 Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc. 0.000 84,811 36,382,223 1.662 Bank of America Corp. 0.000 1,412,855 36,366,888 1.662 Walt Disney Co. 0.000 258,145 34,041,581 1.555 Walmart, Inc. 0.000 241,107 33,477,707 1.530 McDonald's Corp. 0.000 154,571 33,004,000 1.508 Verizon Communications, Inc. 0.000 514,591 30,499,809 1.393 Constellation Brands, Inc. 0.000 159,891 29,496,692 1.348 TJX Cos., Inc. 0.000 535,994 29,367,111 1.342 Texas Instruments, Inc. -

Transportation the Inexorable March of Innovation

2H19 Outlook Transportation The inexorable march of innovation Jay JH Ryu +822-3774-1738 [email protected] Analysts who prepared this report are registered as research analysts in Korea but not in any other jurisdiction, including the U.S. PLEASE SEE ANALYST CERTIFICATIONS AND IMPORTANT DISCLOSURES & DISCLAIMERS IN APPENDIX 1 AT THE END OF REPORT. Contents [Summary] Shares to rebound on earnings improvements in 2H 3 I. Logistics 4 II. Mobility 10 III. Airlines 21 [Conclusion] Market share expansion holds the key 27 Top picks 28 CJ Logistics, Jeju Air Global peer group valuations 30 [Summary] Shares to rebound on earnings improvements in 2H OP of the transportation sector vs. P/B: Valuations have declined amid economic slowdown (Wbn) (x) OP (L) P/B (R) 1,500 2.5 Oil price decline; Air cargo Minimum Global Global High oil prices; greater Oil wage hike; Slowdown in rebound; housing financial Inventory shipping market logistics price oil price Chinese stimulus LCC growth; bubble crisis restocking restructuring momentum rebound M&As growth 1,000 2.0 500 1.5 0 1.0 -500 0.5 -1,000 0.0 1Q04 1Q05 1Q06 1Q07 1Q08 1Q09 1Q10 1Q11 1Q12 1Q13 1Q14 1Q15 1Q16 1Q17 1Q18 Source: FnGuide, Mirae Asset Daewoo Research 3| 2H19 Outlook [Transportation] Mirae Asset Daewoo Research I. Logistics: Easing of oversupply Over the past 15 years, • In the five years following the Asian financial crisis (1998), the domestic logistics market saw annual average regulations have supply growth of more than 10%, as many laid-off workers became independent delivery truck drivers.