A Journal of Onomastics I.M

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities In

“Go eat a bat, Chang!”: On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the Face of COVID-19 Fatemeh Tahmasbi Leonard Schild Chen Ling Binghamton University CISPA Boston University [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Jeremy Blackburn Gianluca Stringhini Yang Zhang Binghamton University Boston University CISPA [email protected] [email protected] [email protected] Savvas Zannettou Max Planck Institute for Informatics [email protected] ABSTRACT KEYWORDS The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives in COVID-19, Sinophobia, Hate Speech, Twitter, 4chan unprecedented ways. In the face of the projected catastrophic conse- ACM Reference Format: quences, most countries have enacted social distancing measures in Fatemeh Tahmasbi, Leonard Schild, Chen Ling, Jeremy Blackburn, Gianluca an attempt to limit the spread of the virus. Under these conditions, Stringhini, Yang Zhang, and Savvas Zannettou. 2021. “Go eat a bat, Chang!”: the Web has become an indispensable medium for information ac- On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the quisition, communication, and entertainment. At the same time, Face of COVID-19. In Proceedings of the Web Conference 2021 (WWW ’21), unfortunately, the Web is being exploited for the dissemination April 19–23, 2021, Ljubljana, Slovenia. ACM, New York, NY, USA, 12 pages. of potentially harmful and disturbing content, such as the spread https://doi.org/10.1145/3442381.3450024 of conspiracy theories and hateful speech towards specific ethnic groups, in particular towards Chinese people and people of Asian 1 INTRODUCTION descent since COVID-19 is believed to have originated from China. -

The N-Word : Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings Anne V

Union College Union | Digital Works Honors Theses Student Work 6-2009 The N-word : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings Anne V. Benfield Union College - Schenectady, NY Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses Part of the Race and Ethnicity Commons, Sociology of Culture Commons, and the Urban Studies and Planning Commons Recommended Citation Benfield, Anne V., "The -wN ord : comprehending the complexity of stratification in American community settings" (2009). Honors Theses. 1433. https://digitalworks.union.edu/theses/1433 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Work at Union | Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Union | Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The N-Word: Comprehending the Complexity of Stratification in American Community Settings By Anne V. Benfield * * * * * * * * * Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for Honors in the Department of Sociology UNION COLLEGE June, 2009 Table of Contents Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Chapter One: Literature Review Etymology 7 Early Uses 8 Fluidity in the Twentieth Century 11 The Commercialization of Nigger 12 The Millennium 15 Race as a Determinant 17 Gender Binary 19 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 23 Generational Difference 25 Chapter Two: Methodology Sociological Theories 29 W.E.B DuBois’ “Double-Consciousness” 34 Qualitative Research Instrument: Focus Groups 38 Chapter Three: Results and Discussion Demographics 42 Generational Difference 43 Class Stratification and the Talented Tenth 47 Gender Binary 51 Race as a Determinant 55 The Ambiguity of Nigger vs. -

Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate

Fordham University DigitalResearch@Fordham Faculty Publications Jewish Studies 2020 Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Fordham University Follow this and additional works at: https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs Part of the History Commons, and the Jewish Studies Commons Recommended Citation Fordham University, "Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate" (2020). Faculty Publications. 2. https://fordham.bepress.com/jewish_facultypubs/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Jewish Studies at DigitalResearch@Fordham. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of DigitalResearch@Fordham. For more information, please contact [email protected], [email protected]. Media Technology & The Dissemination of Hate November 15th, 2019-May 31st 2020 O’Hare Special Collections Fordham University & Center for Jewish Studies Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate Highlights from the Fordham Collection November 15th, 2019-May 31st, 2020 Curated by Sally Brander FCRH ‘20 Clare McCabe FCRH ‘20 Magda Teter, The Shvidler Chair in Judaic Studies with contributions from Students from the class HIST 4308 Antisemitism in the Fall of 2018 and 2019 O’Hare Special Collections Walsh Family Library, Fordham University Table of Contents Preface i Media Technology and the Dissemination of Hate 1 Christian (Mis)Interpretation and (Mis)Representation of Judaism 5 The Printing Press and The Cautionary Tale of One Image 13 New Technology and New Opportunities 22 -

Canadian Inclusive Language Glossary the Canadian Cultural Mosaic Foundation Would Like to Honour And

Lan- guage De- Coded Canadian Inclusive Language Glossary The Canadian Cultural Mosaic Foundation would like to honour and acknowledgeTreaty aknoledgment all that reside on the traditional Treaty 7 territory of the Blackfoot confederacy. This includes the Siksika, Kainai, Piikani as well as the Stoney Nakoda and Tsuut’ina nations. We further acknowledge that we are also home to many Métis communities and Region 3 of the Métis Nation. We conclude with honoring the city of Calgary’s Indigenous roots, traditionally known as “Moh’Kinsstis”. i Contents Introduction - The purpose Themes - Stigmatizing and power of language. terminology, gender inclusive 01 02 pronouns, person first language, correct terminology. -ISMS Ableism - discrimination in 03 03 favour of able-bodied people. Ageism - discrimination on Heterosexism - discrimination the basis of a person’s age. in favour of opposite-sex 06 08 sexuality and relationships. Racism - discrimination directed Classism - discrimination against against someone of a different or in favour of people belonging 10 race based on the belief that 14 to a particular social class. one’s own race is superior. Sexism - discrimination Acknowledgements 14 on the basis of sex. 17 ii Language is one of the most powerful tools that keeps us connected with one another. iii Introduction The words that we use open up a world of possibility and opportunity, one that allows us to express, share, and educate. Like many other things, language evolves over time, but sometimes this fluidity can also lead to miscommunication. This project was started by a group of diverse individuals that share a passion for inclusion and justice. -

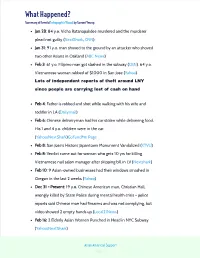

A Timeline of What Has Happened Since

What Happened? Summary of Events/Infographic Visual by Sammi Yeung Jan 28 : 84 y.o. Vicha Ratanapakdee murdered and the murderer plead not guilty (NextShark , CNN ) Jan 31 : 91 y.o. man shoved to the ground by an attacker who shoved two other Asians in Oakland (ABC News ) Feb 3 : 61 y.o. Filipino man got slashed in the subway (CBN). 64 y.o. Vietnamese woman robbed of $1000 in San Jose (Yahoo ) Lots of independent reports of theft around LNY since people are carrying lost of cash on hand Feb 4 : Father is robbed and shot while walking with his wife and toddler in LA (Dailymail ) Feb 6 : Chinese deliveryman had his car stolen while delivering food. His 1 and 4 y.o. children were in the car. ()Yahoo/NextShark GoFundMe Page Feb 8 : San Jose's Historic Japantown Monument Vandalized (KTVU ) Feb 8 : Verdict came out for woman who gets 10 yrs for killing Vietnamese nail salon manager after skipping bill in LV (Nextshark ) Feb 10 : 9 Asian-owned businesses had their windows smashed in Oregon in the last 2 weeks (Yahoo ) Dec 31 - Present : 19 y.o. Chinese American man, Christian Hall, wrongly killed by State Police during mental health crisis - police reports said Chinese man had firearms and was not complying, but video showed 2 empty hands up (Local21News ) Feb 16: 2 Elderly Asian Women Punched in Head in NYC Subway ()Yahoo/NextShark Asian American Support Page 2 Feb 16 : Flushing Asian woman got assaulted - got gashes in her head (ABC7 ) Man was released the next day without bail (Yahoo/NextShark ) Her daughter: https://www.instagram.com/p/CLYarIfDxU6/ -

" Go Eat a Bat, Chang!": on the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the Face of COVID-19

“Go eat a bat, Chang!”: On the Emergence of Sinophobic Behavior on Web Communities in the Face of COVID-19* Fatemeh Tahmasbi1, Leonard Schild2, Chen Ling3, Jeremy Blackburn1, Gianluca Stringhini3, Yang Zhang2, and Savvas Zannettou4 1Binghamton University,2CISPA Helmholtz Center for Information Security, 3Boston University, 4Max Planck Institute for Informatics [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract thought to have originated in China, with the presumed ground zero centered around a wet market in the city of Wuhan in The outbreak of the COVID-19 pandemic has changed our lives the Hubei province [50]. In a few months, SARS-CoV-2 has in an unprecedented way. In the face of the projected catas- spread, allegedly from a bat or pangolin, to essentially every trophic consequences, many countries enforced social distanc- country in the world, resulting in over 1M cases of COVID-19 ing measures in an attempt to limit the spread of the virus. and 50K deaths as of April 2, 2020 [45]. Under these conditions, the Web has become an indispensable Humankind has taken unprecedented steps to mitigating the medium for information acquisition, communication, and en- spread of SARS-CoV-2, enacting social distancing measures tertainment. At the same time, unfortunately, the Web is ex- that go against our very nature. While the repercussions of so- ploited for the dissemination of potentially harmful and disturb- cial distancing measures are yet to be fully understood, one ing content, such as the spread of conspiracy theories and hate- thing is certain: the Web has not only proven essential to the ful speech towards specific ethnic groups, in particular towards approximately normal continuation of daily life, but also as a Chinese people since COVID-19 is believed to have originated tool by which to ease the pain of isolation. -

Civil Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990S. IYSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 343 979 UD 028 599 AUTHOR Chun, Ki-Taek; Zalokar, Nadja TITLE Civil Rights Issues Facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. IYSTITUTION Commission on Civil Rights, Washington, D.C. PUB DATE Feb 92 NOTE 245p. PUB TYPE Reports - Evaluative/Feasibility (142) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC10 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Access to Education; *Asian Americans; *Civil Rights; Educational Discrimination; Elementary Secondary Education; Equal Educetion; *Equal Opportunities (Jobs); Ethnic Discrimination; Higher Education; Immigrants; Minority Groups; *Policy Formation; Public Policy; Racial Bias; *Racial Discrimination; Violence IDENTIFIERS *Commission on Civil Rights ABSTRACT In 1989, the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights held a series of roundtable conferences to learn about the civil rights concerns of Asian Americans within their communities. Using information gathered at these conferences as a point of departure, the Commission undertook this study of the wide-ranging civil rights issues facing Asian Americans in the 1990s. Asian American groups considered in the report are persons having origins in the Far East, Southeast Asia, and the Indian subcontinent. This report presents the results of that investigation. Evidence is presented that Asian Americans face widespread prejudice, discrimination, and barriers to equal opportunity. The following chapters highlight specificareas: (1) "Introduction," an overview of the problems;(2) "Bigotry and Violence Against Asian Americans"; (3) "Police Community Relations"; (4) "Access to Educational Opportunity: Asian American Immigrant Children in Primary and Secondary Schools";(5) "Access to Educational Opportunity: Higher Education"; (6) "Employment Discrimination";(7) "Other Civil Rights Issues Confronting Asian AmericansH; and (8) "Conclusions and Recommendations." More than 40 recommendations for legislative, programmatic, and administrative efforts are made. -

On the Power of Slurring Words and Derogatory Gestures

Charged Expressions: On the Power of Slurring Words and Derogatory Gestures Ralph DiFranco, Ph.D. University of Connecticut, 2016 Slurs have the striking power to promulgate prejudice. Standard semantic and pragmatic theories fail to explain how this works. Drawing on embodied cognition research, I show that metaphorical slurs, descriptive slurs, and slurs that imitate their targets are effective means of transmitting prejudice because they are vehicles for prompting hearers to form mental images that depict targets in unflattering ways or to simulate experiential states such as negative feelings for targets. However, slurs are a heterogeneous group, and there may be no one mechanism by which slurs harm their targets. Some perpetrate a visceral kind of harm – they shock and offend hearers – while others sully hearers with objectionable imagery. Thus, a pluralistic account is needed. Although recent philosophical work on pejoratives has focused exclusively on words, derogation is a broader phenomenon that often constitutively involves various forms of non- verbal communication. This dissertation leads the way into uncharted territory by offering an account of the rhetorical power of iconic derogatory gestures and other non-verbal pejoratives that derogate by virtue of some iconic resemblance to their targets. Like many slurs, iconic derogatory gestures are designed to sully recipients with objectionable imagery. I also address ethical issues concerning the use of pejoratives. For instance, I show that the use of slurs for a powerful majority -

CHSA HP2010.Pdf

The Hawai‘i Chinese: Their Experience and Identity Over Two Centuries 2 0 1 0 CHINESE AMERICA History&Perspectives thej O u r n a l O f T HE C H I n E s E H I s T O r I C a l s OCIET y O f a m E r I C a Chinese America History and PersPectives the Journal of the chinese Historical society of america 2010 Special issUe The hawai‘i Chinese Chinese Historical society of america with UCLA asian american studies center Chinese America: History & Perspectives – The Journal of the Chinese Historical Society of America The Hawai‘i Chinese chinese Historical society of america museum & learning center 965 clay street san francisco, california 94108 chsa.org copyright © 2010 chinese Historical society of america. all rights reserved. copyright of individual articles remains with the author(s). design by side By side studios, san francisco. Permission is granted for reproducing up to fifty copies of any one article for educa- tional Use as defined by thed igital millennium copyright act. to order additional copies or inquire about large-order discounts, see order form at back or email [email protected]. articles appearing in this journal are indexed in Historical Abstracts and America: History and Life. about the cover image: Hawai‘i chinese student alliance. courtesy of douglas d. l. chong. Contents Preface v Franklin Ng introdUction 1 the Hawai‘i chinese: their experience and identity over two centuries David Y. H. Wu and Harry J. Lamley Hawai‘i’s nam long 13 their Background and identity as a Zhongshan subgroup Douglas D. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Asian

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Asian American and African American Masculinities: Race, Citizenship, and Culture in Post -Civil Rights A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Phil osophy in Literature by Chong Chon-Smith Committee in charge: Professor Lisa Lowe, Chair Professor Takashi Fujitani Professor Judith Halberstam Professor Nayan Shah Professor Shelley Streeby Professor Lisa Yoneyama This dissertation of Chong Chon-Smith is approved, and it is acceptable in quality and form for publication on microfilm: __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ __________________________________________________ Chair University of California, San Diego 2006 iii DEDICATION I have had the extraordinary privilege and opportunity to learn from brilliant and committed scholars at UCSD. This dissertation would not have been successful if not for their intellectual rigor, wisdom, and generosity. This dissertation was just a dim thought until Judith Halberstam powered it with her unique and indelible iridescence. Nayan Shah and Shelley Streeby have shown me the best kind of work American Studies has to offer. Their formidable ideas have helped shape these pages. Tak Fujitani and Lisa Yoneyama have always offered me their time and office hospitality whenever I needed critical feedback. -

The Social Life of Slurs

The Social Life of Slurs Geoff Nunberg School of Information, UC Berkeley Jan. 22, 2016 To appear in Daniel Fogal, Daniel Harris, and Matt Moss (eds.) (2017): New Work on Speech Acts (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press). Chaque mot a son histoire. —Jules Gilliéron A Philological Caution The Emergence of Slurs We wear two hats when we talk about slurs, as engaged citizens and as scholars of language. The words had very little theoretical interest for philosophy or linguistic semantics before they took on a symbolic role in the culture wars that broke out in and around the academy in the 1980s.1 But once scholars’ attention was drawn to the topic, they began to discern connections to familiar problems in meta-ethics, semantics, and the philosophy of language. The apparent dual nature of the words—they seem both to describe and to evaluate or express— seemed to make them an excellent test bed for investigations of non-truth-conditional aspects of meaning, of certain types of moral language, of Fregean “coloring,” and of hybrid or “thick” terms, among other things. There are some writers who take slurs purely as a topical jumping-off point for addressing those issues and don’t make any explicit effort to bring their discussions back to the social questions that drew scholars’ attention to the words in the first place. But most seem to feel that their research ought to have some significance beyond the confines of the common room. That double perspective can leave us a little wall-eyed, as we try to track slurs as both a social and linguistic phenomenon. -

"A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 Piano Solo | Twelfth 12Th Street Rag 1914 Euday L

Box Title Year Lyricist if known Composer if known Creator3 Notes # "A" - You're Adorable (The Alphabet Song) 1948 Buddy Kaye Fred Wise Sidney Lippman 1 piano solo | Twelfth 12th Street Rag 1914 Euday L. Bowman Street Rag 1 3rd Man Theme, The (The Harry Lime piano solo | The Theme) 1949 Anton Karas Third Man 1 A, E, I, O, U: The Dance Step Language Song 1937 Louis Vecchio 1 Aba Daba Honeymoon, The 1914 Arthur Fields Walter Donovan 1 Abide With Me 1901 John Wiegand 1 Abilene 1963 John D. Loudermilk Lester Brown 1 About a Quarter to Nine 1935 Al Dubin Harry Warren 1 About Face 1948 Sam Lerner Gerald Marks 1 Abraham 1931 Bob MacGimsey 1 Abraham 1942 Irving Berlin 1 Abraham, Martin and John 1968 Dick Holler 1 Absence Makes the Heart Grow Fonder (For Somebody Else) 1929 Lewis Harry Warren Young 1 Absent 1927 John W. Metcalf 1 Acabaste! (Bolero-Son) 1944 Al Stewart Anselmo Sacasas Castro Valencia Jose Pafumy 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Ac-cent-tchu-ate the Positive 1944 Johnny Mercer Harold Arlen 1 Accidents Will Happen 1950 Johnny Burke James Van Huesen 1 According to the Moonlight 1935 Jack Yellen Joseph Meyer Herb Magidson 1 Ace In the Hole, The 1909 James Dempsey George Mitchell 1 Acquaint Now Thyself With Him 1960 Michael Head 1 Acres of Diamonds 1959 Arthur Smith 1 Across the Alley From the Alamo 1947 Joe Greene 1 Across the Blue Aegean Sea 1935 Anna Moody Gena Branscombe 1 Across the Bridge of Dreams 1927 Gus Kahn Joe Burke 1 Across the Wide Missouri (A-Roll A-Roll A-Ree) 1951 Ervin Drake Jimmy Shirl 1 Adele 1913 Paul Herve Jean Briquet Edward Paulton Adolph Philipp 1 Adeste Fideles (Portuguese Hymn) 1901 Jas.