Reflections on Hebrews

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Star Channels, Jan. 5-11, 2020

JANUARY 5 - 11, 2020 staradvertiser.com HEARING VOICES In an innovative, exciting departure from standard television fare, NBC presents Zoe’s Extraordinary Playlist. Jane Levy stars as the titular character, Zoey Clarke, a computer programmer whose extremely brainy, rigid nature often gets in the way of her ability to make an impression on the people around her. Premiering Tuesday, Jan. 7, on NBC. Delivered over 877,000 hours of programming Celebrating 30 years of empowering our community voices. For our community. For you. olelo.org 590191_MilestoneAds_2.indd 2 12/27/19 5:22 PM ON THE COVER | ZOEY’S EXTRAORDINARY PLAYLIST A penny for your songs ‘Zoey’s Extraordinary Playlist’ ...,” narrates the first trailer for the show, “... her new ability, when she witnesses an elabo- what she got, was so much more.” rate, fully choreographed performance of DJ premieres on NBC In an event not unlike your standard super- Khaled’s “All I Do is Win,” but Mo only sees “a hero origin story, an MRI scan gone wrong bunch of mostly white people drinking over- By Sachi Kameishi leaves Zoey with the ability to access people’s priced coffee.” TV Media innermost thoughts and feelings. It’s like she It’s a fun premise for a show, one that in- becomes a mind reader overnight, her desire dulges the typical musical’s over-the-top, per- f you’d told me a few years ago that musicals to fully understand what people want from formative nature as much as it subverts what would be this culturally relevant in 2020, I her seemingly fulfilled. -

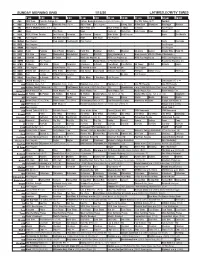

Sunday Morning Grid 1/12/20 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 1/12/20 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Face the Nation (N) News College Basketball Michigan State at Purdue. (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) Å NBC4 News Paid Program Saving Pets A New Leaf Champion Bensinger Monster 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Hearts of Rock-Park Jack Hanna News Ocean Paid 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday Joel Osteen Jeremiah Joel Osteen Jentzen Mike Webb Paid Program Icons The World’s 1 1 FOX Paid Program Fox News Sunday News The Issue Paid Program 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Freethought Paid Program News The Issue 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Kitchen Mexican Christina Joanne Simply Ming Food 50 2 8 KCET Kid Stew Curious Wunderkind Wunderkind Darwin’s Biz Kid$ Aging Backwards 3 Brain Secrets With Dr. Michael Merzenich Å 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Paid NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva (N) 4 0 KTBN Pathway Win Walk Prince Carpenter A Jackson In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Ed Young Bethel Kelinda Hagee 4 6 KFTR Paid Program Super Genios (TVY) El mundo es tuyo El mundo es tuyo Paid Program 5 0 KOCE Nature Cat Nature Cat Wild Kratts Wild Kratts Odd Squad Odd Squad Antiques Roadshow Antiques Nature (N) Å NOVA Å 5 2 KVEA Paid La Liga Fútbol Premier League La Liga Paid Program 5 6 KDOC Perry Stone In Search Lift Up Paid Cath. -

Greetings Faithful Reader and Welcome Once Again to Cosmic

Greetings faithful reader and welcome A couple of decades ago, whilst still a once again to Cosmic Masque. student, I wrote an unsolicited submis- sion of a third Doctor novel for the BBC We’ve got some great stuff for you in Past Doctor range. Expecting a swift this issue including Neil Davies story rejection, I was delighted to receive a ‘Devil Woman’ which concludes what two page response clearly showing that began in ‘Reunion of The Rani’ last my book had been read and analysed issue. at length. There are features on Colourisation Encouraged, I reworked the idea as a and 3D as well as the second part of sixth Doctor script for the then nascent my feature on the Twitch marathon this Big Finish range (at a time when they time covering the Second Doctor. considered unsolicited manuscripts). Again, I received positive comments, We’ve also got an interview with The but it was felt that the story was un- Greatest Show In The Galaxy’s Flower workable due to various considerations Girl and our usual plethora of reviews including the number of characters. for you to devour. Sadly, real life took over and post- So sit back, put your feet up and delve degree I had to concentrate on working into this issue. Dickensian hours and gaining my ac- countancy qualifications. The career Enjoy! took over and life became the mundan- ity of work and sleep and eating chips. Rik Writing was put on hold indefinitely as mortgages and family took hold. Then Russell T. Davies gave Doctor Who back to the masses, enthralling Published by The Doctor Who Appreciation Society the UK (and beyond) including my twin P O Box 1011, Horsham, RH10 9RZ, UK children. -

A Thirteenth Doctorate

Number 43 Trinity 2019 A THIRTEENTH DOCTORATE Series Eleven reviewed Minor or major corrections, or referral? Virgin New Adventures • Meanings of the Mara The Time of the Doctor • Big Chief Studios • and more Number 43 Trinity 2019 [email protected] [email protected] oxforddoctorwho-tidesoftime.blog users.ox.ac.uk/~whosoc twitter.com/outidesoftime twitter.com/OxfordDoctorWho facebook.com/outidesoftime facebook.com/OxfordDoctorWho The Wheel of Fortune We’re back again for a new issue of Tides! After all this time anticipating her arrival true, Jodie Whittaker’s first series as the Doctor has been and gone, so we’re dedicating a lot of coverage this issue to it. We’ve got everything from reviews of the series by new president Victoria Walker, to predictions from society stalwart Ian Bayley, ratings from Francis Stojsavljevic, and even some poetry from Will Shaw. But we’re not just looking at Series Eleven. We’re looking back too, with debates on the merits of the Capaldi era, a spirited defence of The Time of the Doctor, and drifting back through the years, even a look at the Virgin New Adventures! Behind the scenes, there’s plenty of “change, my dear, and not a moment too soon!” We bid adieu to valued comrades like Peter, Francis and Alfred as new faces are welcomed onto the committee, with Victoria now helming the good ship WhoSoc, supported by new members Rory, Dahria and Ben, while familiar faces look on wistfully from the port bow. It’s also the Society’s Thirtieth Anniversary this year, which will be marked by a party in Mansfield College followed by a slap-up dinner; an event which promises to make even the most pampered Time Lord balk at its extravagance! On a personal note, it’s my last year before I graduate Oxford, at least for now, so when the next issue is out, I’ll be writing from an entirely new place. -

If It's New Year's Eve, It Must Be Ryan Seacrest

Visit Our Showroom To Find The Perfect Lift Bed For You! Dec. 27, 2019 - Jan. 2, 2020 Ryan Seacrest hosts “Dick Clark’s New Year’s Rockin’ Eve With Ryan Seacrest“ Tuesday on ABC. 2 x 2" ad 300 N Beaton St | Corsicana | 903-874-82852 x 2" ad M-F 9am-5:30pm | Sat 9am-4pm milesfurniturecompany.com FREE DELIVERY IN LOCAL AREA WA-00114341 V A H R E G N F K N U F F G A Your Key 2 x 3" ad I Z F O Z J O S E P H E O T P B G O P E F A H T E O L V A R To Buying R T A W F P Z E P X L R U Y I and Selling! S L T R Q M A R T I N E Z L L 2 x 3.5" ad C L O J U S T I C E D Q D O M A D K S M C F F S H E E J R F P U I R A X M F L T D Y A K F O O T V S N C B L I U I W L E V J L L O Y G O R H C A Q A H Z A L I Z W H E J I L G M U L E I X C T N I K L U A A J S U B K G G A I E Z A E R N O U G E T E V F D C P X D S E N K A A S X A Y B E S K I L T R A B “Deputy” on Fox Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) Bill (Hollister) (Stephen) Dorff Los Angeles (County) Place your classified Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 Cade (Ward) (Brian) Van Holt Justice ad in the Waxahachie Daily Light, Merchandise High-End 2 x 3" ad Brianna (Bishop) (Bex) Taylor-Klaus Drama Midlothian Mirror and Ellis Joseph (Harris) (Shane Paul) McGhie Politics County Trading1 Post! x 4" ad Deal Merchandise Word Search Paula (Reyes) (Yara) Martinez (New) Sheriff Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item If it’s New Year’s Eve, it priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily Light, must be Ryan Seacrest Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading2 x 3.5" Post ad and online at waxahachietx.com All specials are pre-paid. -

Pag. 4 • DOCTOR WOW • PSYCHIC PAPER

P U L L T O O P E N È più grande all’interno! THE MAGAZINE • DOCTOR WEAR • DOCTOR WOW Consigli e ispirazioni per Gossip Cosmico Whovians vacanzieri in questa e altre - pag. 4 galassie - pag. 14 • DOCTOR IF • PSYCHIC PAPER Una rubrica dedicata La nostra rubrica alle fanfiction del della posta mondo Whovian - pag. 23 - pag. 6 numero 14 luglio 2021 4 Doctor Wear! Consigli e ispirazioni per Whovians vacanzieri 6 Doctor if 2021 Ogni mese vi regaliamo una fanfiction: una storia ambientata nell’universo di Doctor Who, in cui l’immaginazione di un fan muove e rein- venta i personaggi della nostra serie preferita! 14 Doctor wow! Gossip Cosmico in questa e altre galassie 16 Enigmistica whovian Giochi a tema Whovian: cruciverba e tanto altro! 21 The Shadow Proclamation luglio Metti da parte pesci, leoni e sagittari: prova il nostro Oroscopo Whovian, l’unico adattabile a più di 5 milioni di forme di vita differenti, liq- uide, solide o gassose! 25 Psychic Paper La nostra rubrica della posta... copertina, retro e grafica creati da: Bruno Alicata con l’aiuto dello staff editor testi: SakiJune, Tardis rubriche a cura di: Dalek Oba Seven Saki June Tardis Eleven Brig Alex Kingston (River Song) Inglese da parte di padre e tedesca da parte di madre, l’abbiamo conosciuta anche come Elizabeth Corday nella serie ER… tra l’altro Elizabeth è il suo secondo nome! Si è sposata tre volte e il suo primo marito è stato l’attore Ralph Fiennes. Un dimanche après-midi à l'Île de la Grande Jatte di George Seurat VWORP VWORP! Pull to Open è più grande all’interno! Ogni -

Doctor Who Episode Data, 2005-20

Episode Information BBC IMDB Series # Title Date Year XMAS AI Chart Rating # User-Raters 1 1 Rose 3/26/2005 2005 0 76 7 7.5 7,027 1 2 The End of the World 4/2/2005 2005 0 76 19 7.6 6,136 1 3 The Unquiet Dead 4/9/2005 2005 0 80 15 7.6 7,578 1 4 Aliens of London 4/16/2005 2005 0 82 18 7.0 5,516 1 5 World War III 4/23/2005 2005 0 81 20 7.0 5,327 1 6 Dalek 4/30/2005 2005 0 84 14 8.7 6,065 1 7 The Long Game 5/7/2005 2005 0 81 17 7.1 5,253 1 8 Father's Day 5/14/2005 2005 0 83 17 8.4 5,839 1 9 The Empty Child 5/21/2005 2005 0 84 21 9.2 7,138 1 10 The Doctor Dances 5/28/2005 2005 0 85 18 9.1 6,547 1 11 Boom Town 6/4/2005 2005 0 82 18 7.1 5,013 1 12 Bad Wolf 6/11/2005 2005 0 86 19 8.7 5,727 1 13 The Parting of the Ways 6/18/2005 2005 0 89 17 9.1 6,196 2 0 The Christmas Invasion 12/25/2005 2005 1 84 9 8.1 5,692 2 1 New Earth 4/15/2006 2006 0 85 9 7.4 5,281 2 2 Tooth and Claw 4/22/2006 2006 0 83 10 7.8 5,418 2 3 School Reunion 4/29/2006 2006 0 85 12 8.3 5,795 2 4 The Girl in the Fireplace 5/6/2006 2006 0 84 13 9.3 9,064 2 5 Rise of the Cybermen 5/13/2006 2006 0 86 6 7.8 5,050 2 6 The Age of Steel 5/20/2006 2006 0 86 15 7.9 4,994 2 7 The Idiot's Lantern 5/27/2006 2006 0 84 18 6.7 5,175 2 8 The Impossible Planet 6/3/2006 2006 0 85 18 8.7 5,817 2 9 The Satan Pit 6/10/2006 2006 0 86 19 8.8 6,027 2 10 Love & Monsters 6/17/2006 2006 0 76 15 6.1 6,150 2 11 Fear Her 6/24/2006 2006 0 83 20 6.0 5,405 2 12 Army of Ghosts 7/1/2006 2006 0 86 7 8.5 5,252 2 13 Doomsday 7/8/2006 2006 0 89 8 9.3 7,291 3 0 The Runaway Bride 12/25/2006 2006 1 84 10 7.6 5,388 3 1 Smith -

Lorna Jowett Is a Reader in Television Studies at the University Of

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by NECTAR 1 The Girls Who Waited? Female Companions and Gender in Doctor Who Lorna Jowett Abstract: Science fiction has the potential to offer something new in terms of gender representation. This doesn’t mean it always delivers on this potential. Amid the hype surrounding the 50th anniversary of Doctor Who, the longest running science fiction series on television, a slightly critical edge is discernable in the media coverage concerning the casting of the twelfth Doctor and issues of representation in the series. This paper examines Doctor Who in the broader context of TV drama and changes to the TV industry, analysing the series’ gender representation, especially in the 2005 reboot, and focusing largely on the female ‘companions’. Keywords: gender representation, television, feminism, BBC. When I put together an earlier version of this paper two years ago, I discovered a surprising gap in the academic study of Doctor Who around gender. Gender in science fiction has often been studied, after all, and Star Trek, another science fiction television series starting in the 1960s (original run 1966-69) and continued via spin-offs and reboots, has long been analysed in terms of gender. So why not Doctor Who? Admittedly, Doctor Who’s creators have no clear philosophy about trying to represent a more equal society, as with the utopian Trek. The lack of scholarship on gender in Doctor Who may also be part of a lack of scholarship generally on the series—academic study of it is just gaining momentum, and only started to accumulate seriously in the last five years. -

Year 8 Project – Black Lives Matter

Year 8 project – Black Lives Matter Hello Year 8s, This week we will be focusing on Black Lives Matter (BLM) and the civil rights movement. If you have access to BBC iPlayer watch the Dr Who episode on Rosa Parks! https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/b0bpwm2m/doctor-who-series-11-3- rosa • Literacy Task – Write a letter/ debating skills/is racism getting worse? • Numeracy Task – Solving the calculations. • Science Task – Identify the contributions of famous Black Scientist. • Humanities Task – The Montgomery Bus Boycott/Civil Rights and Black Lives Matter • Art Task – Create a design to raise awareness of BLM in schools/ Take a virtual Tour of art work by a famous Black artist. Stay safe ☺ ☺ From Miss Masud and Mr Rogers Note to parents – Tasks are labelled with *, **, or *** based on their level of challenge, *** being the most challenging. Lesson – Literacy-Black Lives Matter Task – Write a personal response towards racism in the UK.* (The tasks have been given *, ** and *** to help you choose which one is best for you.) 0 First up: Write a personal response to this song- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nPOxEo7NtpQ Consider how the lyrics highlighted below make you feel. What are your thoughts? What are your views? “Black children, their childhood stolen from them.” “Robbed of our names and our language.” “These are the things we gotta discuss.” “The colour of my skin they comparing it to sin.” “All men and women were created equal. Including Black Americans.” The song made me feel ____________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ I think _________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ ________________________________________________________________________ Lesson – Literacy-Black Lives Matter Task – Write some arguments for and against the protests. -

Star Channels, July 14-20

JULY 14 - 20, 2019 staradvertiser.com PREACH ON It’s 1956 and change is in the air. Sidney Chambers (James Norton) is feeling adrift and there is a hip new reverend in town (Tom Brittney). He is a man of the people and he is shaking things up with his progressiveness. Will the changing of the times leave Det. Insp. Geordie Keating (Robson Green) behind? Find out when Grantchester returns after a two-year absence. Airing Sunday, July 14, on PBS. HONORING HARRY B. SORIA, JR. TONIGHT | 10PM | CHANNEL 53 Join the fun as Territorial Airwaves, the longest continuously running radio show in Hawaii, celebrates its 40th Anniversary with a magical evening of incredible entertainment including Raiatea 40TH ANNIVERSARY Helm, Ho¶okena, Na Hoa, Kimo Alama Keaulana & olelo.org CELEBRATION Lei Hulu and Alan Akaka & the Islanders. ON THE COVER | GRANTCHESTER Hot for preacher James Norton’s time in series by James Runcie, the period drama chaplain and man of the people who embod- ‘Grantchester’ comes to an end follows the adventures of a charismatic ies the changing post-war world. The hip Anglican vicar and former World War II reverend rides a motorcycle and listens to Scots Guards officer Sidney Chambers rock ‘n’ roll. He is young and does not pos- By Francis Babin (James Norton, “McMafia”) as he develops sess the post-war emotional baggage that TV Media a penchant for sleuthing. After receiving a many others, including Sidney, struggle with. visit from a deceased man’s mistress who Much like his fellow man of the cloth, he is ecently, investigative journalist Billy believes his death was not a suicide but a considered a “boat-rocker” who embraces Jensen popularized the term “citizen murder, Sidney is implored to investigate the future. -

Star Channels, Feb. 2-8, 2020

staradvertiser.com FEBRUARY 2 - 8, 2020 COVERT CROONERS Season 3 of The Masked Singer premieres right after Super Bowl LIV, and the new installment of this simultaneously strange and beautiful series promises to be bigger and better than ever. Host Nick Cannon returns along with the previous seasons’ judges: actors Ken Jeong and Jenny McCarthy are back on the panel with musicians Robin Thicke and Nicole Scherzinger. Premiering Sunday, Feb. 2, on NBC. WEEKLY NEWS UPDATE LIVE @ THE LEGISLATURE Join Senate and House leadership as they discuss upcoming legislation and issues of importance to the community. TUESDAY, 8:30AM | CHANNEL 49 | olelo.org/49 olelo.org ON THE COVER | THE MASKED SINGER Musical mystery Season 3 of ‘The Masked tery celebrities — more than any season so artists by trade — such as the Empress of far. Soul, Gladys Knight, who took third place in Singer’ premieres after Unlike most performance competitions, Season 1, and last season’s high-ranking Super Bowl LIV “The Masked Singer” does not recruit previ- competitors Patti LaBelle, Seal and runner- ously unknown talents to vie for a prize. In up Chris Daughtry — most are taking a leap, By Breanna Henry this reality series, it’s celebrities who face off amazing judges, fans and even themselves TV Media against one another for fan votes, and each with their vocal chops. Simply imagining the episode features spectacular musical per- celebs that could appear on the upcoming here is an absolute smorgasbord of formances. The catch is that the celebrities season of “The Masked Singer” is fun — and reality television to choose from these are wearing elaborate costumes that con- imagining is all we can do. -

Texts and Practices: Readings in Critical Discourse Analysis

Texts and Practices Texts and Practices provides an essential introduction to the theory and practice of Critical Discourse Analysis. Using insights from this challenging new method of linguistic analysis, the contributors to this collection reveal the ways in which language can be used as a means of social control. The essays in Texts and Practices: • Demonstrate how Critical Discourse Analysis can be applied to a variety of written and spoken texts. • Deconstruct data from a range of contexts, countries and disciplines. • Expose hidden patterns of discrimination and inequalities of power. Texts and Practices, which includes specially commissioned papers from a range of distinguished authors, provides a state-of-the-art overview of Critical Discourse Analysis. As such it represents an important contribution to this developing field and an essential text for all advanced students of language, media and cultural studies. Carmen Rosa Caldas-Coulthard is Professor of English and Applied Linguistics at the Federal University of Santa Catarina, Brazil. Her most recent publications are contributions to the edited collections Techniques of Description (1993) and Advances in Written Text Analysis (1994), both published by Routledge. Malcolm Coulthard is Professor of English Language and Linguistics at the University of Birmingham. His most recent publications with Routledge are Advances in Spoken Discourse Analysis (1992) and Advances in Written Text Analysis (1994). He also edits the journal Forensic Linguistics. Texts and Practices Readings in Critical Discourse Analysis Edited by Carmen Rosa Caldas-Coulthard and Malcolm Coulthard London and New York First published 1996 by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EE This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2003.