Statues of New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Year's Music

This is a reproduction of a library book that was digitized by Google as part of an ongoing effort to preserve the information in books and make it universally accessible. https://books.google.com fti E Y LAKS MV5IC 1896 juu> S-q. SV- THE YEAR'S MUSIC. PIANOS FOR HIRE Cramer FOR HARVARD COLLEGE LIBRARY Pianos BY All THE BEQUEST OF EVERT JANSEN WENDELL (CLASS OF 1882) OF NEW YORK Makers. 1918 THIS^BQQKJS FOR USE 1 WITHIN THE LIBRARY ONLY 207 & 209, REGENT STREET, REST, E.C. A D VERTISEMENTS. A NOVEL PROGRAMME for a BALLAD CONCERT, OR A Complete Oratorio, Opera Recital, Opera and Operetta in Costume, and Ballad Concert Party. MADAME FANNY MOODY AND MR. CHARLES MANNERS, Prima Donna Soprano and Principal Bass of Royal Italian Opera, Covent Garden, London ; also of 5UI the principal ©ratorio, dJrtlustra, artii Sgmphoiu) Cxmctria of ©wat Jfvitain, Jtmmca anb Canaba, With their Full Party, comprising altogether Five Vocalists and Three Instrumentalists, Are now Booking Engagements for the Coming Season. Suggested Programme for Ballad and Opera (in Costume) Concert. Part I. could consist of Ballads, Scenas, Duets, Violin Solos, &c. Lasting for about an hour and a quarter. Part II. Opera or Operetta in Costume. To play an hour or an hour and a half. Suggested Programme for a Choral Society. Part I. A Small Oratorio work with Chorus. Part II. An Operetta in Costume; or the whole party can be engaged for a whole work (Oratorio or Opera), or Opera in Costume, or Recital. REPERTOIRE. Faust (Gounod), Philemon and Baucis {Gounod) (by arrangement with Sir Augustus Harris), Maritana (Wallace), Bohemian Girl (Balfe), and most of the usual Oratorios, &c. -

Daguerreian Annual 1990-2015: a Complete Index of Subjects

Daguerreian Annual 1990–2015: A Complete Index of Subjects & Daguerreotypes Illustrated Subject / Year:Page Version 75 Mark S. Johnson Editor of The Daguerreian Annual, 1997–2015 © 2018 Mark S. Johnson Mark Johnson’s contact: [email protected] This index is a work in progress, and I’m certain there are errors. Updated versions will be released so user feedback is encouraged. If you would like to suggest possible additions or corrections, send the text in the body of an email, formatted as “Subject / year:page” To Use A) Using Adobe Reader, this PDF can be quickly scrolled alphabetically by sliding the small box in the window’s vertical scroll bar. - or - B) PDF’s can also be word-searched, as shown in Figure 1. Many index citations contain keywords so trying a word search will often find other instances. Then, clicking these icons Figure 1 Type the word(s) to will take you to another in- be searched in this Adobe Reader Window stance of that word, either box. before or after. If you do not own the Daguerreian Annual this index refers you to, we may be able to help. Contact us at: [email protected] A Acuna, Patricia 2013: 281 1996: 183 Adams, Soloman; microscopic a’Beckett, Mr. Justice (judge) Adam, Hans Christian d’types 1995: 176 1995: 194 2002/2003: 287 [J. A. Whipple] Abbot, Charles G.; Sec. of Smithso- Adams & Co. Express Banking; 2015: 259 [ltr. in Boston Daily nian Institution deposit slip w/ d’type engraving Evening Transcript, 1/7/1847] 2015: 149–151 [letters re Fitz] 2014: 50–51 Adams, Zabdiel Boylston Abbott, J. -

The Sculptures of Upper Summit Avenue

The Sculptures of Upper Summit Avenue PUBLIC ART SAINT PAUL: STEWARD OF SAINT PAUL’S CULTURAL TREASURES Art in Saint Paul’s public realm matters: it manifests Save Outdoor Sculpture (SOS!) program 1993-94. and strengthens our affection for this city — the place This initiative of the Smithsonian Institution involved of our personal histories and civic lives. an inventory and basic condition assessment of works throughout America, carried out by trained The late 19th century witnessed a flourishing of volunteers whose reports were filed in a national new public sculptures in Saint Paul and in cities database. Cultural Historian Tom Zahn was engaged nationwide. These beautiful works, commissioned to manage this effort and has remained an advisor to from the great artists of the time by private our stewardship program ever since. individuals and by civic and fraternal organizations, spoke of civic values and celebrated heroes; they From the SOS! information, Public Art Saint illuminated history and presented transcendent Paul set out in 1993 to focus on two of the most allegory. At the time these gifts to states and cities artistically significant works in the city’s collection: were dedicated, little attention was paid to long Nathan Hale and the Indian Hunter and His Dog. term maintenance. Over time, weather, pollution, Art historian Mason Riddle researched the history vandalism, and neglect took a profound toll on these of the sculptures. We engaged the Upper Midwest cultural treasures. Conservation Association and its objects conservator Kristin Cheronis to examine and restore the Since 1994, Public Art Saint Paul has led the sculptures. -

Music and the American Civil War

“LIBERTY’S GREAT AUXILIARY”: MUSIC AND THE AMERICAN CIVIL WAR by CHRISTIAN MCWHIRTER A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of History in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2009 Copyright Christian McWhirter 2009 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT Music was almost omnipresent during the American Civil War. Soldiers, civilians, and slaves listened to and performed popular songs almost constantly. The heightened political and emotional climate of the war created a need for Americans to express themselves in a variety of ways, and music was one of the best. It did not require a high level of literacy and it could be performed in groups to ensure that the ideas embedded in each song immediately reached a large audience. Previous studies of Civil War music have focused on the music itself. Historians and musicologists have examined the types of songs published during the war and considered how they reflected the popular mood of northerners and southerners. This study utilizes the letters, diaries, memoirs, and newspapers of the 1860s to delve deeper and determine what roles music played in Civil War America. This study begins by examining the explosion of professional and amateur music that accompanied the onset of the Civil War. Of the songs produced by this explosion, the most popular and resonant were those that addressed the political causes of the war and were adopted as the rallying cries of northerners and southerners. All classes of Americans used songs in a variety of ways, and this study specifically examines the role of music on the home-front, in the armies, and among African Americans. -

Boston Common and the Public Garden

WalkBoston and the Public Realm N 3 minute walk T MBTA Station As Massachusetts’ leading advocate for safe and 9 enjoyable walking environments, WalkBoston works w with local and state agencies to accommodate walkers | in all parts of the public realm: sidewalks, streets, bridges, shopping areas, plazas, trails and parks. By B a o working to make an increasingly safe and more s attractive pedestrian network, WalkBoston creates t l o more transportation choices and healthier, greener, n k more vibrant communities. Please volunteer and/or C join online at www.walkboston.org. o B The center of Boston’s public realm is Boston m Common and the Public Garden, where the pedestrian m o network is easily accessible on foot for more than o 300,000 Downtown, Beacon Hill and Back Bay workers, n & shoppers, visitors and residents. These walkways s are used by commuters, tourists, readers, thinkers, t h talkers, strollers and others during lunch, commutes, t e and on weekends. They are wonderful places to walk o P — you can find a new route every day. Sample walks: u b Boston Common Loops n l i • Perimeter/25 minute walk – Park St., Beacon St., c MacArthur, Boylston St. and Lafayette Malls. G • Central/15 minute walk – Lafayette, Railroad, a MacArthur Malls and Mayor’s Walk. r d • Bandstand/15 minute walk – Parade Ground Path, e Beacon St. Mall and Long Path. n Public Garden Loops • Perimeter/15 minute walk – Boylston, Charles, Beacon and Arlington Paths. • Swans and Ducklings/8 minute walk – Lagoon Paths. Public Garden & Boston Common • Mid-park/10 minute walk – Mayor’s, Haffenreffer Walks. -

Geographical List of Public Sculpture-1

GEOGRAPHICAL LIST OF SELECTED PERMANENTLY DISPLAYED MAJOR WORKS BY DANIEL CHESTER FRENCH ♦ The following works have been included: Publicly accessible sculpture in parks, public gardens, squares, cemeteries Sculpture that is part of a building’s architecture, or is featured on the exterior of a building, or on the accessible grounds of a building State City Specific Location Title of Work Date CALIFORNIA San Francisco Golden Gate Park, Intersection of John F. THOMAS STARR KING, bronze statue 1888-92 Kennedy and Music Concourse Drives DC Washington Gallaudet College, Kendall Green THOMAS GALLAUDET MEMORIAL; bronze 1885-89 group DC Washington President’s Park, (“The Ellipse”), Executive *FRANCIS DAVIS MILLET AND MAJOR 1912-13 Avenue and Ellipse Drive, at northwest ARCHIBALD BUTT MEMORIAL, marble junction fountain reliefs DC Washington Dupont Circle *ADMIRAL SAMUEL FRANCIS DUPONT 1917-21 MEMORIAL (SEA, WIND and SKY), marble fountain reliefs DC Washington Lincoln Memorial, Lincoln Memorial Circle *ABRAHAM LINCOLN, marble statue 1911-22 NW DC Washington President’s Park South *FIRST DIVISION MEMORIAL (VICTORY), 1921-24 bronze statue GEORGIA Atlanta Norfolk Southern Corporation Plaza, 1200 *SAMUEL SPENCER, bronze statue 1909-10 Peachtree Street NE GEORGIA Savannah Chippewa Square GOVERNOR JAMES EDWARD 1907-10 OGLETHORPE, bronze statue ILLINOIS Chicago Garfield Park Conservatory INDIAN CORN (WOMAN AND BULL), bronze 1893? group !1 State City Specific Location Title of Work Date ILLINOIS Chicago Washington Park, 51st Street and Dr. GENERAL GEORGE WASHINGTON, bronze 1903-04 Martin Luther King Jr. Drive, equestrian replica ILLINOIS Chicago Jackson Park THE REPUBLIC, gilded bronze statue 1915-18 ILLINOIS Chicago East Erie Street Victory (First Division Memorial); bronze 1921-24 reproduction ILLINOIS Danville In front of Federal Courthouse on Vermilion DANVILLE, ILLINOIS FOUNTAIN, by Paul 1913-15 Street Manship designed by D.C. -

Adventure Playground: Essentially, to a Place of Pleasure—That Today It Surrounds Us, Everywhere, Having Quietly John V

The city’s onscreen prominence is so taken for granted today that it is hard to imagine that as late as 1965, the last year of Robert F. Wagner’s mayoralty, New York hardly appeared in films at all. That year, only two features were shot substantially in the city: The Pawnbroker, an early landmark in the career of veteran New York director Sidney Lumet, and A Thousand Clowns, directed by Fred Coe, which used extensive location work to “open up” a Broadway stage hit of a few years earlier by the playwright Herb Gardner. The big change came with Wagner’s successor, John V. Lindsay—who, soon after taking office in 1966, made New York the first city in history to encourage location filmmaking: establishing a simple, one-stop permit process through a newly created agency (now called the Mayor’s Office of Film, Theatre and Broadcasting), creating a special unit of the Police Department to assist filmmakers, and ordering all city agencies and departments to cooperate with producers and directors (1). The founding of the Mayor’s Film Office—the first agency of its kind in the world—remains to this day one of the Lindsay administration’s signal achievements, an innovation in governance which has been replicated by agencies or commissions in almost every city and state in the Union, and scores of countries and provinces around the world. In New York, it helped to usher in a new industry, now generating over five billion dollars a year in economic activity and bringing work to more than 100,000 New Yorkers: renowned directors and stars, working actors and technicians, and tens of thousands of men and women employed by supporting businesses—from equipment rental houses, to scenery shops, to major studio complexes that now rival those of Southern California. -

Download the 2019 Map & Guide

ARCHITECTURAL AND CULTURAL Map &Guide FRIENDS of the Upper East Side Historic Districts Architectural and Cultural Map and Guide Founded in 1982, FRIENDS of the Upper East Side Historic Districts is an independent, not-for-profit membership organization dedicated to preserving the architectural legacy, livability, and sense of place of the Upper East Side by monitoring and protecting its seven Historic Districts, 131 Individual Landmarks, and myriad significant buildings. Walk with FRIENDS as we tour some of the cultural and architectural sites that make the Upper East Side such a distinctive place. From elegant apartment houses and mansions to more modest brownstones and early 20th-century immigrant communities, the Upper East Side boasts a rich history and a wonderfully varied built legacy. With this guide in hand, immerse yourself in the history and architecture of this special corner of New York City. We hope you become just as enchanted by it as we are. FRIENDS’ illustrated Architectural and Cultural Map and Guide includes a full listing of all of the Upper East Side’s 131 Individual Landmarks. You can find the location of these architectural gems by going to the map on pages 2-3 of the guide and referring to the numbered green squares. In the second section of the guide, we will take you through the history and development of the Upper East Side’s seven Historic Districts, and the not landmarked, though culturally and architecturally significant neighborhood of Yorkville. FRIENDS has selected representative sites that we feel exemplify each district’s unique history and character. Each of the districts has its own color-coded map with easy-to-read points that can be used to find your own favorite site, or as a self-guided walking tour the next time you find yourself out strolling on the Upper East Side. -

Using Dry Ice Blasting to Remove Lacquer Coating

Article: The Case for Cold: Using Dry Ice Blasting to Remove Lacquer Coating from TheKing Jagiello Monument in Central Park Author: Matt Reiley Source: Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Twenty-Four, 2017 Pages: 269–292 Editors: Emily Hamilton and Kari Dodson, with Tony Sigel Program Chair ISSN (print version) 2169-379X ISSN (online version) 2169-1290 © 2019 by American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works 727 15th Street NW, Suite 500, Washington, DC 20005 (202) 452-9545 www.culturalheritage.org Objects Specialty Group Postprints is published annually by the Objects Specialty Group (OSG) of the American Institute for Conservation (AIC). It is a conference proceedings volume consisting of papers presented in the OSG sessions at AIC Annual Meetings. Under a licensing agreement, individual authors retain copyright to their work and extend publications rights to the American Institute for Conservation. Unless otherwise noted, images are provided courtesy of the author, who has obtained permission to publish them here. This article is published in the Objects Specialty Group Postprints, Volume Twenty-Four, 2017. It has been edited for clarity and content. The article was peer-reviewed by content area specialists and was revised based on this anonymous review. Responsibility for the methods and materials described herein, however, rests solely with the author(s), whose article should not be considered an official statement of the OSG or the AIC. OSG2017-Reiley.indd 1 12/9/19 4:10 PM THE CASE FOR COLD: USING DRY ICE BLASTING TO REMOVE LACQUER COATING FROM THE KING JAGIELLO MONUMENT IN CENTRAL PARK MATT REILEY This case study provides an overview of the use of dry ice blasting as a suitable method for Incralac coating removal on a heroic- scaled equestrian bronze sculpture as part of the development of a sustainable program of protective coatings maintenance. -

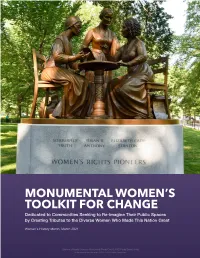

TOOLKIT for CHANGE Dedicated to Communities Seeking to Re-Imagine Their Public Spaces by Creating Tributes to the Diverse Women Who Made This Nation Great

MONUMENTAL WOMEN’S TOOLKIT FOR CHANGE Dedicated to Communities Seeking to Re-imagine Their Public Spaces by Creating Tributes to the Diverse Women Who Made This Nation Great Women’s History Month, March 2021 Women’s Rights Pioneers Monument Photo Credit: NYC Parks/Daniel Avila © Monumental Women 2021 – All Rights Reserved Table of Contents Introduction 1 A Framework For Structure, Accounting, Budgeting And Taxation 5 Suggestions For Launching A Women’s History Education Campaign 12 Intergenerational Leadership: Inspiring Youth Activism 16 Creating And Amplifying Partnerships 19 Fundraising Tips 22 Other Fundraising Issues To Consider 28 Publicity And Marketing: Public Relations 33 A Happy Ending 37 Welcome to Monumental Women’s Toolkit for Change! This document was created by members of the Board of Monumental Women with experience and expertise in particular areas of the process of honoring more women and people of color in public spaces. We hope that the information contained in the Toolkit will serve as a guide to others who are embarking on their own eforts to reimagine their communities’ public spaces. Officers and Board Members: President - Pam Elam Vice President for Operations - Namita Luthra Vice President for Programs - Brenda Berkman Secretary - Ariel Deutsch Treasurer - David Spaulding Judaline Cassidy Gary Ferdman Coline Jenkins Serina Liu Eileen Macdonald Meridith Maskara Myriam Miedzian Heather Nesle Monumental Women thanks ongoing partner Jane Walker by Johnnie Walker, the first-ever female iteration of the Johnnie Walker Striding Man and a symbol of progress in gender equality, for its support of our project and collaboration in bringing this Toolkit to fruition. Introduction INTRODUCTION By Pam Elam, Monumental Women President It's not often that you have the chance to be part of something truly historic. -

Renaissance Art and Architecture

Renaissance Art and Architecture from the libraries of Professor Craig Hugh Smyth late Director of the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University; Director, I Tatti, Florence; Ph.D., Princeton University & Professor Robert Munman Associate Professor Emeritus of the University of Illinois; Ph.D., Harvard University 2552 titles in circa 3000 physical volumes Craig Hugh Smyth Craig Hugh Smyth, 91, Dies; Renaissance Art Historian By ROJA HEYDARPOUR Published: January 1, 2007 Craig Hugh Smyth, an art historian who drew attention to the importance of conservation and the recovery of purloined art and cultural objects, died on Dec. 22 in Englewood, N.J. He was 91 and lived in Cresskill, N.J. The New York Times, 1964 Craig Hugh Smyth The cause was a heart attack, his daughter, Alexandra, said. Mr. Smyth led the first academic program in conservation in the United States in 1960 as the director of the Institute of Fine Arts at New York University. Long before he began his academic career, he worked in the recovery of stolen art. After the defeat of Germany in World War II, Mr. Smyth was made director of the Munich Central Collecting Point, set up by the Allies for works that they retrieved. There, he received art and cultural relics confiscated by the Nazis, cared for them and tried to return them to their owners or their countries of origin. He served as a lieutenant in the United States Naval Reserve during the war, and the art job was part of his military service. Upon returning from Germany in 1946, he lectured at the Frick Collection and, in 1949, was awarded a Fulbright research fellowship, which took him to Florence, Italy. -

PLAZA HOTEL INTERIOR Designation Report

PLAZA HOTEL INTERIOR Designation Report New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission July 12, 2005 Designation List 366 LP-2174 PLAZA HOTEL INTERIOR: TABLE OF CONTENTS Site Description 2 Testimony at Public Hearing 2 Essay Summary 3 Fifth Avenue and the Site 4 Construction and Opening of Plaza Hotel 4 Hotel Architecture 5 Frederic Sterry 6 Henry Janeway Hardenbergh 6 Warren & Wetmore 7 The 1905-07 Design of the Plaza Hotel’s Interiors 8 1919-1922 addition and 1929 Grand Ballroom 11 The Hilton Plaza (1943-1953) 13 Plaza Hotel (1953 to present) 14 Plaza Hotel Social History 14 Site Plans 21 Individual Room Entries The Edwardian Room 24 59th Street Lobby 29 Fifth Avenue Lobby and Vestibules 31 Grand Ballroom 35 Corridor and Foyer Main Corridors 44 The Oak Bar 49 The Oak Room 52 The Palm Court 57 Terrace Room 62 Corridor, Foyer Stairways Findings and Designation 72 Report researched and written by Research Department Mary Beth Betts, Director of Research, Michael Caratzas, Gale Harris, Virginia Kurshan, Matthew A. Postal, Donald Presa, and Jay Shockley All photos by Carl Forster PLAZA HOTEL INTERIOR Plaza Hotel, ground floor interior consisting of the Fifth Avenue vestibules, Lobby, corridor to the east of the Palm Court, the Palm Court, Terrace Room, corridor to the north of the Palm Court connecting to the 59th Street Lobby and the Oak Room, foyers to the Edwardian Room from the corridor to the north of the Palm Court and the 59th Street Lobby, the Edwardian Room, 59th Street Lobby and vestibule, the Oak Room and the Oak Bar, corridor