PLAZA HOTEL INTERIOR Designation Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Murdoch's Global Plan For

CNYB 05-07-07 A 1 5/4/2007 7:00 PM Page 1 TOP STORIES Portrait of NYC’s boom time Wall Street upstart —Greg David cashes in on boom on the red hot economy in options trading Page 13 PAGE 2 ® New Yorkers are stepping to the beat of Dancing With the Stars VOL. XXIII, NO. 19 WWW.NEWYORKBUSINESS.COM MAY 7-13, 2007 PRICE: $3.00 PAGE 3 Times Sq. details its growth, worries Murdoch’s about the future PAGE 3 global plan Under pressure, law firms offer corporate clients for WSJ contingency fees PAGE 9 421-a property tax Times, CNBC and fight heads to others could lose Albany; unpacking out to combined mayor’s 2030 plan Fox, Dow Jones THE INSIDER, PAGE 14 BY MATTHEW FLAMM BUSINESS LIVES last week, Rupert Murdoch, in a ap images familiar role as insurrectionist, up- RUPERT MURDOCH might bring in a JOINING THE PARTY set the already turbulent media compatible editor for The Wall Street Journal. landscape with his $5 billion offer for Dow Jones & Co. But associ- NEIL RUBLER of Vantage Properties ates and observers of the News media platform—including the has acquired several Corp. chairman say that last week planned Fox Business cable chan- thousand affordable was nothing compared with what’s nel—and take market share away housing units in the in store if he acquires the property. from rivals like CNBC, Reuters past 16 months. Campaign staffers They foresee a reinvigorated and the Financial Times. trade normal lives for a Dow Jones brand that will combine Furthermore, The Wall Street with News Corp.’s global assets to Journal would vie with The New chance at the White NEW POWER BROKERS House PAGE 39 create the foremost financial news York Times to shape the national and information provider. -

PERSHING SQUARE VIADUCT (Park Avenue Viaduct), Park Avenue from 40Th Street to Grand Central Terminal (42Nd Street), Borough of Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission September 23, 1980, Designation List 137 LP-1127 PERSHING SQUARE VIADUCT (Park Avenue Viaduct), Park Avenue from 40th Street to Grand Central Terminal (42nd Street), Borough of Manhattan. Built 1917-19; architects Warren & Wetmore. Landmark Site: The property bounded by a line running easward parallel with the northern curb line of East 40th Street, a line running northward to the edge of Tax Map Block 1280, Lot 1, parallel with the eastern wall of the viaduct, a line running westward along the edge of Tax Map Block 1280, Lot 1, and a line running southward parallel with the western wall of the viaduct to the point of beginning. On March 11, 1980, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Pershing Square Viaduct (Park Avenue Viaduct) and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No. 9). The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with the provisions of law. Four witnesses spoke in favor of designation. There were no speakers in opposition to designation. DESCRIPTION AND ANALYSIS Located at Park Avenue and 42nd Street, tfie Pershing Square Viaduct was constructed tn 1917-1919. The viaduct extends from 40th Street to Grand Central Terminal at 42nd Street, linking upper and lower Park Avenue by way of elevated drives that make a circuit around the terminal building and descend to ground level at 45th Street. Designed in 1912 by the architectural firm of Warren & Wetmore, the viaduct was conceived as part of the original 1903 plan for the station by the firm of Reed & Stem. -

RITZ TOWER, 465 Park Avenue (Aka 461-465 Park Avenue, and 101East5t11 Street), Manhattan

Landmarks Preservation Commission October 29, 2002, Designation List 340 LP-2118 RITZ TOWER, 465 Park Avenue (aka 461-465 Park Avenue, and 101East5T11 Street), Manhattan. Built 1925-27; Emery Roth, architect, with Thomas Hastings. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1312, Lot 70. On July 16, 2002 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation as a Landmark of the Ritz Tower, and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site (Item No.2). The hearing had been advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Ross Moscowitz, representing the owners of the cooperative spoke in opposition to designation. At the time of designation, he took no position. Mark Levine, from the Jamestown Group, representing the owners of the commercial space, took no position on designation at the public hearing. Bill Higgins represented these owners at the time of designation and spoke in favor. Three witnesses testified in favor of designation, including representatives of State Senator Liz Kruger, the Landmarks Conservancy and the Historic Districts Council. In addition, the Commission has received letters in support of designation from Congresswoman Carolyn Maloney, from Community Board Five, and from architectural hi storian, John Kriskiewicz. There was also one letter from a building resident opposed to designation. Summary The Ritz Tower Apartment Hotel was constructed in 1925 at the premier crossroads of New York's Upper East Side, the comer of 57t11 Street and Park A venue, where the exclusive shops and artistic enterprises of 57t11 Street met apartment buildings of ever-increasing height and luxury on Park Avenue. -

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 22, 2016, Designation List 490 LP-2579

Landmarks Preservation Commission November 22, 2016, Designation List 490 LP-2579 YALE CLUB OF NEW YORK CITY 50 Vanderbilt Avenue (aka 49-55 East 44th Street), Manhattan Built 1913-15; architect, James Gamble Rogers Landmark site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1279, Lot 28 On September 13, 2016, the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of the Yale Club of New York City and the proposed designation of the related Landmark Site. The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Six people spoke in support of designation, including representatives of the Yale Club of New York City, Manhattan Borough President Gale A. Brewer, Historic Districts Council, New York Landmarks Conservancy, and the Municipal Art Society of New York. The Real Estate Board of New York submitted written testimony in opposition to designation. State Senator Brad Hoylman submitted written testimony in support of designation. Summary The Yale Club of New York City is a Renaissance Revival-style skyscraper at the northwest corner of Vanderbilt Avenue and East 44th Street. For more than a century it has played an important role in East Midtown, serving the Yale community and providing a handsome and complementary backdrop to Grand Central Terminal. Constructed on property that was once owned by the New York Central Railroad, it stands directly above two levels of train tracks and platforms. This was the ideal location to build the Yale Club, opposite the new terminal, which serves New Haven, where Yale University is located, and at the east end of “clubhouse row.” The architect was James Gamble Rogers, who graduated from Yale College in 1889 and attended the Ecole des Beaux Arts in Paris during the 1890s. -

Peter Ward, 93, Very Active in Law Associations, Sailing Clubs, RTM Member

Darienite News for Darien https://darienite.com Peter Ward, 93, Very Active in Law Associations, Sailing Clubs, RTM Member Author : David Gurliacci Categories : Obituaries Tagged as : Darien Obituaries 2018, Darien Obituary, Darien Obituary 2018, Darien Obituary June 2018 Date : June 6, 2018 Peter Minton Ward, 93, of Darien died peacefully on Sunday, June 3, 2018. A beloved husband, he is survived by his wife Audrey of 60 years. He was born on Dec. 24, 1924 in New York City to Francis T. and Alice W. Ward. He attended The Green Vale School, ’39, on Long Island, St. George's School, ’43, Newport, RI, where he was a trustee and chair of the Board of Trustees, and then an active honorary trustee, the University of Pennsylvania, ‘47 in Philadelphia and its Law School ‘49, where he was an associate editor of the Law Review and, after coming to New York, president of the New York Alumni Society. Of Counsel to Chadbourne & Parke, LLP, New York City, (recently merged with Norton Rose Fulbright) where he had been a partner for over 35 years. During his professional career in New York, he served on various committees of the New York City and New York State Bar Associations and of the American Bar Association. He served also as a director and a vice president and member of the executive committee of the Legal Aid Society of New York and as a director of the New York Lawyers for the Public Interest. Activities in Darien included service on its Representative Town Meeting and the Vestry and as senior warden of St. -

Vornado Realty Trust

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM 8-K Current report filing Filing Date: 2017-06-05 | Period of Report: 2017-06-05 SEC Accession No. 0001104659-17-037358 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER VORNADO REALTY TRUST Mailing Address Business Address 888 SEVENTH AVE 888 SEVENTH AVE CIK:899689| IRS No.: 221657560 | State of Incorp.:MD | Fiscal Year End: 0317 NEW YORK NY 10019 NEW YORK NY 10019 Type: 8-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-11954 | Film No.: 17889956 212-894-7000 SIC: 6798 Real estate investment trusts VORNADO REALTY LP Mailing Address Business Address 888 SEVENTH AVE 210 ROUTE 4 EAST CIK:1040765| IRS No.: 133925979 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 1231 NEW YORK NY 10019 PARAMUS NJ 07652 Type: 8-K | Act: 34 | File No.: 001-34482 | Film No.: 17889957 212-894-7000 SIC: 6798 Real estate investment trusts Copyright © 2017 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, DC 20549 FORM 8-K CURRENT REPORT PURSUANT TO SECTION 13 OR 15(d) OF THE SECURITIES EXCHANGE ACT OF 1934 Date of Report (Date of earliest event reported): June 5, 2017 VORNADO REALTY TRUST (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Charter) Maryland No. 001-11954 No. 22-1657560 (State or Other (Commission (IRS Employer Jurisdiction of File Number) Identification No.) Incorporation) VORNADO REALTY L.P. (Exact Name of Registrant as Specified in Charter) Delaware No. 001-34482 No. 13-3925979 (State or Other (Commission (IRS Employer Jurisdiction of -

Monthly Market Report

MAY 2017 Monthly Market Report SALES SUMMARY .......................... 2 HISTORICAL PERFORMANCE ....... 4 NEW DEVELOPMENTS ................... 2 5 NOTABLE NEW LISTINGS .............. 4 6 SNAPSHOT ...................................... 7 7 8 CityRealty is the website for NYC real estate, providing high-quality listings and tailored agent matching for pro- spective apartment buyers, as well as in-depth analysis of the New York real estate market. MONTHLY MARKET REPORT MAY 2017 Summary MOST EXPENSIVE SALES The average sales price and number of Manhattan apartment sales both increased in the four weeks leading up to April 1. The average price for an apartment—taking into account both condo and co-op sales—was $2.3 million, up from $2.2 million the prior month. The number of recorded sales, 817, was up from the 789 recorded in the preceding month. AVERAGE SALES PRICE CONDOS AND CO-OPS $65.1M 432 Park Avenue, #83 $2.3 Million 6+ Beds, 6+ Baths Approx. 8,055 ft2 ($8,090/ft2) The average price of a condo was $3.6 million and the average price of a co-op was $1.2 million. There were 389 condo sales and 428 co-op sales. RESIDENTIAL SALES 817 $1.9B UNITS GROSS SALES The top sale this month was in 432 Park Avenue. Unit 83 in the property sold for $65 million. The apartment, one of the largest in 432 Park, has six+ bedrooms, six+ bathrooms, and measures 8,055 square feet. $43.9M 443 Greenwich Street, #PHH The second most expensive sale this month was in the recent Tribeca condo conversion at 5 Beds, 6+ Baths 443 Greenwich Street. -

Course Syllabus Jump to Today Modern American Architecture Columbia University, GSAPP Spring 2020, Mondays 11-1 Professor Jorge Otero- Pailos Ph.D

Course Syllabus Jump to Today Modern American Architecture Columbia University, GSAPP Spring 2020, Mondays 11-1 Professor Jorge Otero- Pailos Ph.D. TA: Shuyi [email protected] M.S TA: Mariana Ávila [email protected] Course Description: This course is a survey of American Modern Architecture since the country’s first centennial. As America ascended to its current position of hegemony during the late 19th and 20th centuries, its architects helped refashion the built environment to serve the needs of a growing and ever-diverse population. Hand in hand with the satisfaction of pragmatic requirements, American architects were called upon to fulfill deeper psychological wants, such as the country’s desire to have a national History. The American complex about the brevity, artificiality, and exterior dependency of its history, structured, with varying degrees of intensity, the evolution of the architectural discipline. Out of this deep-seated, and by no means exhausted, anxiety about producing, preserving, and identifying American history, came a sophisticated architectural culture; one capable of foiling, exploiting, subverting, and manipulating the various contradictions of modernity. From the standpoint of this relationship between history and modernity, we will analyze the American architectural struggle to be progressive and accepted, exceptional and customary, and to simultaneously capture the future and the past. Each lecture will analyze the production and reception of built (and written) works by renowned figures and anonymous builders. The question of History will help us discern the terms of engagement between architecture and other disciplines over time, such as: preservation, planning, real estate development, politics, health, ecology, sociology, and philosophy. -

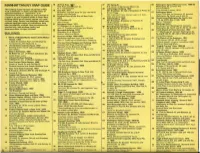

Manhattan N.V. Map Guide 18

18 38 Park Row. 113 37 101 Spring St. 56 Washington Square Memorial Arch. 1889·92 MANHATTAN N.V. MAP GUIDE Park Row and B kman St. N. E. corner of Spring and Mercer Sts. Washington Sq. at Fifth A ve. N. Y. Starkweather Stanford White The buildings listed represent ali periods of Nim 38 Little Singer Building. 1907 19 City Hall. 1811 561 Broadway. W side of Broadway at Prince St. First erected in wood, 1876. York architecture. In many casesthe notion of Broadway and Park Row (in City Hall Perk} 57 Washington Mews significant building or "monument" is an Ernest Flagg Mangin and McComb From Fifth Ave. to University PIobetween unfortunate format to adhere to, and a portion of Not a cast iron front. Cur.tain wall is of steel, 20 Criminal Court of the City of New York. Washington Sq. North and E. 8th St. a street or an area of severatblocks is listed. Many glass,and terra cotta. 1872 39 Cable Building. 1894 58 Housesalong Washington Sq. North, Nos. 'buildings which are of historic interest on/y have '52 Chambers St. 1-13. ea. )831. Nos. 21-26.1830 not been listed. Certain new buildings, which have 621 Broadway. Broadway at Houston Sto John Kellum (N.W. corner], Martin Thompson replaced significant works of architecture, have 59 Macdougal Alley been purposefully omitted. Also commissions for 21 Surrogates Court. 1911 McKim, Mead and White 31 Chembers St. at Centre St. Cu/-de-sac from Macdouga/ St. between interiorsonly, such as shops, banks, and 40 Bayard-Condict Building. -

Appetite for Autumn 34Th Street Style Knicks & Nets

NOV 2014 NOV ® MUSEUMS | Knicks & Nets Knicks 34th Street Style Street 34th Restaurants offering the flavors of Fall NBA basketball tips-off in New York City York New in tips-off basketball NBA Appetite For Autumn For Appetite Styles from the world's brands beloved most BROADWAY | DINING | ULTIMATE MAGAZINE FOR NEW YORK CITY FOR NEW YORK MAGAZINE ULTIMATE SHOPPING NYC Monthly NOV2014 NYCMONTHLY.COM VOL. 4 NO.11 44159RL_NYC_MONTHLY_NOV.indd All Pages 10/7/14 5:18 PM SAMPLE SALE NOV 8 - NOV 16 FOR INFO VISIT: ANDREWMARC.COM/SAMPLESALE 1OOO EXCLUSIVES • 1OO DESIGNERS • 1 STORE Contents Cover Photo: Woolworth Building Lobby © Valerie DeBiase. Completed in 1913 and located at 233 Broadway in Manhattan’s financial district, The Woolworth building is an NYC landmark and was at the time the world’s tallest building. Its historic, ornate lobby is known for its majestic, vaulted ceiling, detailed sculptures, paintings, bronze fixtures and grand marble staircase. While generally not open to the public, this neo-Gothic architectural gem is now open for tours with limited availability. (woolworthtours.com) FEATURES Top 10 things to do in November Encore! Encore! 16 26 Feel the energy that only a live performance in the Big Apple can produce 34th Street Style 18 Make your way through this stretch of Midtown, where some of the biggest outposts from global NYC Concert Spotlight brands set up shop 28 Fitz and the Tantrums Appetite For Autumn 30 The Crowd Goes Wild 20 As the seasons change, so do these restaurant's NBA basketball tips off in NYC menus, -

Download the 2019 Map & Guide

ARCHITECTURAL AND CULTURAL Map &Guide FRIENDS of the Upper East Side Historic Districts Architectural and Cultural Map and Guide Founded in 1982, FRIENDS of the Upper East Side Historic Districts is an independent, not-for-profit membership organization dedicated to preserving the architectural legacy, livability, and sense of place of the Upper East Side by monitoring and protecting its seven Historic Districts, 131 Individual Landmarks, and myriad significant buildings. Walk with FRIENDS as we tour some of the cultural and architectural sites that make the Upper East Side such a distinctive place. From elegant apartment houses and mansions to more modest brownstones and early 20th-century immigrant communities, the Upper East Side boasts a rich history and a wonderfully varied built legacy. With this guide in hand, immerse yourself in the history and architecture of this special corner of New York City. We hope you become just as enchanted by it as we are. FRIENDS’ illustrated Architectural and Cultural Map and Guide includes a full listing of all of the Upper East Side’s 131 Individual Landmarks. You can find the location of these architectural gems by going to the map on pages 2-3 of the guide and referring to the numbered green squares. In the second section of the guide, we will take you through the history and development of the Upper East Side’s seven Historic Districts, and the not landmarked, though culturally and architecturally significant neighborhood of Yorkville. FRIENDS has selected representative sites that we feel exemplify each district’s unique history and character. Each of the districts has its own color-coded map with easy-to-read points that can be used to find your own favorite site, or as a self-guided walking tour the next time you find yourself out strolling on the Upper East Side. -

City of Wauwatosa, Wisconsin

City of Wauwatosa, Wisconsin Architectural and Historical Intensive Survey Report of Residential Properties Phase 2 By Rowan Davidson, Associate AIA & Jennifer L. Lehrke, AIA, NCARB Legacy Architecture, Inc. 605 Erie Avenue, Suite 101 Sheboygan, Wisconsin 53081 Project Director Joseph R. DeRose, Survey & Registration Historian Wisconsin Historical Society Division of Historic Preservation – Public History 816 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 Sponsoring Agency Wisconsin Historical Society Division of Historic Preservation – Public History 816 State Street Madison, Wisconsin 53706 2019-2020 Acknowledgments This program receives Federal financial assistance for identification and protection of historic properties. Under Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973, and the Age Discrimination Act of 1975, as amended, the U.S. Department of the Interior prohibits discrimination on the basis of race, color, national origin, or disability or age in its federally assisted programs. If you believe you have been discriminated against in any program, activity, or facility as described above, or if you desire further information, please write to Office of the Equal Opportunity, National Park Service, 1849 C Street NW, Washington, DC 20240. The activity that is the subject of this intensive survey report has been financed entirely with Federal Funds from the National Park Service, U.S. Department of the Interior, and administered by the Wisconsin Historical Society. However, the contents and opinions do not necessarily reflect the views or policies of the Department of the Interior or the Wisconsin Historical Society, nor does the mention of trade names or commercial products constitute endorsement or recommendation by the Department of the Interior or the Wisconsin Historical Society.