2013-06-13 Keel Boat Manual V1.8

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2010 Year Book

2010 YEAR BOOK www.massbaysailing.org $5.00 HILL & LOWDEN, INC. YACHT SALES & BROKERAGE J boat dealer for Massachusetts and southern new hampshire Hill & Lowden, Inc. offers the full range of new J Boat performance sailing yachts. We also have numerous pre-owned brokerage listings, including quality cruising sailboats, racing sailboats, and a variety of powerboats ranging from runabouts to luxury cabin cruisers. Whether you are a sailor or power boater, we will help you find the boat of your dreams and/or expedite the sale of your current vessel. We look forward to working with you. HILL & LOWDEN, INC. IS CONTINUOUSLY SEEKING PRE-OWNED YACHT LISTINGS. GIVE US A CALL SO WE CAN DISCUSS THE SALE OF YOUR BOAT www.Hilllowden.com 6 Cliff Street, Marblehead, MA 01945 Phone: 781-631-3313 Fax: 781-631-3533 Table of Contents ______________________________________________________________________ INFORMATION Letter to Skippers ……………………………………………………. 1 2009 Offshore Racing Schedule ……………………………………………………. 2 2009 Officers and Executive Committee …………… ……………............... 3 2009 Mass Bay Sailing Delegates …………………………………………………. 4 Event Sponsoring Organizations ………………………………………................... 5 2009 Season Championship ………………………………………………………. 6 2009 Pursuit race Championship ……………………………………………………. 7 Salem Bay PHRF Grand Slam Series …………………………………………….. 8 PHRF Marblehead Qualifiers ……………………………………………………….. 9 2009 J105 Mass Bay Championship Series ………………………………………… 10 PHRF EVENTS Constitution YC Wednesday Evening Races ……………………………………….. 11 BYC Wednesday Evening -

Fleet Boat Sail # Owner Keel Rig Mods Base PHRF Adjust Your

Boat Information PHRF Rating Adjustments All Your Jib O.S. Jib Dacron O.S. Base Assigned 130% Roller Non IB Fleet Boat Sail # Owner Keel Rig Mods Adjust Head <130 Cruising Spin PHRF PHRF to Furler Spin Prop Sail % Blue / Pole Rating 145% White -3 +6 +9 +3 +6 +12 -3 +6 Blue/White Cape Dory Typ. TY 72 Harrington Fixed Std No 276 27 303 6 3 6 12 Blue/White Capri 26 14 Smith Fin Std No 237 27 264 6 3 6 12 Blue/White Catalina 22 2191 Kroh Swing Std No 270 12 282 12 Blue/White Catalina 22 Mk-II 15351 Walker Wing Std No 273 12 285 12 Blue/White Catalina 22 Sport 15582 Fox Swing Std No 252 12 264 12 Blue/White Catalina 25 2925 Gummer Swing Std No 243 18 261 6 12 Blue/White Catalina 25 3736 Hollingsworth Swing Tall No 240 27 267 6 3 6 12 Blue/White Catalina 25 4639 George Swing Std No 243 18 261 6 12 Blue/White Catalina 25 5101 Hickok Swing Std No 243 18 261 6 12 Blue/White Catalina 25 5130 Earnhart Swing Std No 243 18 261 6 12 Blue/White Catalina 25 5884 Kelly Wing Tall No 246 21 267 3 6 12 Blue/White Catalina 250 406 Alyea Swing Std No 243 21 264 3 6 12 Blue/White Hunter 216 H216 Zimmowitch CB Std No 222 18 240 6 12 Blue/White Hunter 23 788 Lessick Swing Std No 246 18 264 6 12 Blue/White Hunter 23 H23 Kirch Swing Std No 246 18 264 6 12 Blue/White Hunter 23.5 H23.5 Elmore CB Std No 252 30 282 9 3 6 12 Blue/White Hunter 240 24489 Merriman Swing Td No 243 30 273 9 3 6 12 Blue/White Hunter 26.5 167 Crowther Wing Std No 189 27 216 6 3 6 12 Blue/White Lindenberg 22 22189 McGarvey Retract FR No 216 0 216 Blue/White MacGregor 26 4393 Grant Swing Std -

Mainsail Trim Pointers, Reefing and Sail Care for the Beneteau Oceanis Series

Neil Pryde Sails International 1681 Barnum Avenue Stratford, CT 06614 203-375-2626 [email protected] INTERNATIONAL DESIGN AND TECHNICAL OFFICE Mainsail Trim Pointers, Reefing and Sail Care for the Beneteau Oceanis Series The following points on mainsail trim apply both to the Furling and Classic mainsails we produce for Beneteau USA and the Oceanis Line of boats. In sailing the boats we can offer these general ideas and observations that will apply to the 311’s through to the newest B49. Mainsail trim falls into two categories, upwind and downwind. MAINSAIL TRIM: The following points on mainsail trim apply both to the Furling and Classic mainsail, as the concepts are the same. Mainsail trim falls into two categories, upwind and downwind. Upwind 1. Upwind in up to about 8 knots true wind the traveler can be brought to weather of centerline. This ensures that the boom will be close centerline and the leech of the sail in a powerful upwind mode. 2. The outhaul should be eased 2” / 50mm at the stopper, easing the foot of the mainsail away from the boom about 8”/200mm 3. Mainsheet tension should be tight enough to have the uppermost tell tail on the leech streaming aft about 50% of the time in the 7- 12 true wind range. For those with furling mainsails the action of furling and unfurling the sail can play havoc with keeping the telltales on the sail and you may need to replace them from time to time. Mainsail outhaul eased for light air upwind trim You will find that the upper tell tail will stall and fold over to the weather side of the sail about 50% of the time in 7-12 knots. -

The Weather Helm Issue (Rev 20 02 2020)

Corbin 39 – the weather helm issue (rev 20 02 2020) Synopsis The subject of weather helm comes up repeatedly when discussing the Corbin 39 and not all of the folklore is justified. This note attempts to summarise the issue and to relate it to sufficient evidence, and to qualitative theory, that we can be reasonably certain of the situation. Remember - It is possible to overpower a yacht and induce weather helm, what we are trying to do is identify excessive weather helm. The key take-away is that the excessive weather helm was a genuine issue, which affected all the mk1 cutters irrespective of whether they were equipped with the taller double-spreader mast or the shorter single-spreader mast, provided that the mast was set in the intended aft mast position. Perhaps this was worse in the mk1 tallmast vs the mk1 shortmast, but we are not at all certain of that. All the mk1’s that had the forestay relocated onto a 3-foot long bowsprit were later able to alleviate this to an extent. The mk 1’s that have reduced the area of their main by shortening the mainsail boom & foot (or used in-mast furling) have reportedly completely eliminated this weather helm. All other versions including the mk1 ketches and all the mk2 cutters & ketches appear to be completely unaffected. This is the first openly published version of this analysis. Previous drafts were incomplete and drew erroneous conclusions in some areas due to an absence of reliable data. That has now been overcome as further evidence has come forwards, and so there are material differences between this version and previous drafts. -

How the Beaufort Scale Affects Your Sail Plan

How the Beaufort scale affects your sail plan The Beaufort scale is a measurement that relates wind speed to observed conditions at sea. Used in the sea area forecast it allows sailors to anticipate the condition that they are likely to face. Modern cruising yachts have become wider over the years to allow more room inside the boat when berthed. This offers the occupants a large living space but does have an effect on the handling of the boat. A wide beam, relatively short keel and rudder mean that if they have too much sail up they have a greater tendency to broach into the wind. Broaching, although dramatic for those onboard, is nothing more than the boat turning into the wind and is easy to rectify by carrying less sail. If the helm is struggling to keep the boat in a straight line then the boat has too much ‘weather helm’ i.e. the boat keeps turning into the wind- in this instance it is necessary to reduce sail. Racer/cruisers are often narrower than their cruising counter parts, with longer keels and rudders which mean they are less likely to broach, but often more difficult to sail with a small crew. Cruising yachts often have large overlapping jibs or genoas and relevantly small main sails. This allows the sail area to be reduced quickly and easily simply by furling away some head sail. The main sail is used to balance boat as the main drive comes from the head sail. Racer cruisers will often have smaller jibs and larger main sails, so reducing the sail area means reefing the main sail first and using the jib to balance the boat. -

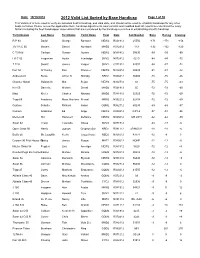

2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap

Date: 10/19/2012 2012 Valid List Sorted by Base Handicap Page 1 of 30 This Valid List is to be used to verify an individual boat's handicap, and valid date, and should not be used to establish handicaps for any other boats not listed. Please review the appilication form, handicap adjustments, boat variants and modified boat list reports to understand the many factors including the fleet handicapper observations that are considered by the handicap committee in establishing a boat's handicap Yacht Design Last Name First Name Yacht Name Fleet Date Sail Number Base Racing Cruising R P 90 David George Rambler NEW2 R021912 25556 -171 -171 -156 J/V I R C 66 Meyers Daniel Numbers MHD2 R012912 119 -132 -132 -120 C T M 66 Carlson Gustav Aurora NEW2 N081412 50095 -99 -99 -90 I R C 52 Fragomen Austin Interlodge SMV2 N072412 5210 -84 -84 -72 T P 52 Swartz James Vesper SMV2 C071912 52007 -84 -87 -72 Farr 50 O' Hanley Ron Privateer NEW2 N072412 50009 -81 -81 -72 Andrews 68 Burke Arthur D Shindig NBD2 R060412 55655 -75 -75 -66 Chantier Naval Goldsmith Mat Sejaa NEW2 N042712 03 -75 -75 -63 Ker 55 Damelio Michael Denali MHD2 R031912 55 -72 -72 -60 Maxi Kiefer Charles Nirvana MHD2 R041812 32323 -72 -72 -60 Tripp 65 Academy Mass Maritime Prevail MRN2 N032212 62408 -72 -72 -60 Custom Schotte Richard Isobel GOM2 R062712 60295 -69 -69 -57 Custom Anderson Ed Angel NEW2 R020312 CAY-2 -57 -51 -36 Merlen 49 Hill Hammett Defiance NEW2 N020812 IVB 4915 -42 -42 -30 Swan 62 Tharp Twanette Glisse SMV2 N071912 -24 -18 -6 Open Class 50 Harris Joseph Gryphon Soloz NBD2 -

Sailing Course Materials Overview

SAILING COURSE MATERIALS OVERVIEW INTRODUCTION The NCSC has an unusual ownership arrangement -- almost unique in the USA. You sail a boat jointly owned by all members of the club. The club thus has an interest in how you sail. We don't want you to crack up our boats. The club is also concerned about your safety. We have a good reputation as competent, safe sailors. We don't want you to spoil that record. Before we started this training course we had many incidents. Some examples: Ran aground in New Jersey. Stuck in the mud. Another grounding; broke the tiller. Two boats collided under the bridge. One demasted. Boats often stalled in foul current, and had to be towed in. Since we started the course the number of incidents has been significantly reduced. SAILING COURSE ARRANGEMENT This is only an elementary course in sailing. There is much to learn. We give you enough so that you can sail safely near New Castle. Sailing instruction is also provided during the sailing season on Saturdays and Sundays without appointment and in the week by appointment. This instruction is done by skippers who have agreed to be available at these times to instruct any unkeyed member who desires instruction. CHECK-OUT PROCEDURE When you "check-out" we give you a key to the sail house, and you are then free to sail at any time. No reservation is needed. But you must know how to sail before you get that key. We start with a written examination, open book, that you take at home. -

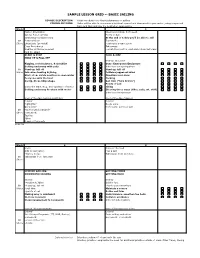

SLG 2018-03.Xlsx

SAMPLE LESSON GRID -- BASIC SAILING COURSE DESCRIPTION A fun introduction to the fundamentals of sailing COURSE OUTCOME Sailor will be able to maneuver a keelboat upwind and downwind in open water ,using proper sail trim, and tack and jibe the boat when appropriate Week 1 2 Harbor Orientation Emergency Equip. & Proceed. Safety, Fun, Learning Points of Sail Emergency Contact Forms At the end of today you'll be able to sail On Personal Gear Teamwork: Shore Lifejackets (provided) --sailing is a team sport Class Procedures Takeaways: Weather & Marine Forecast --what stood out for each sailor from last class Find the Wind START & STOP TACK & JIBE HEAD UP & FALL OFF Review: Checklist Rigging, nomenclature, & checklist ! ! ! ! Demo Emergency Equipment ! ! ! ! Getting underway with sails ! ! ! ! Intro to mooring departure On Head up, fall off ! ! ! ! Head up, fall off ! ! ! ! Water Introduce tacking & jibing ! ! ! ! Telltales/apparent wind ! ! ! ! Start, stop, safety position in open water ! ! ! ! Directing your crew ! ! ! ! Everyone sails the boat ! ! ! ! Tacking ! ! ! ! De-rig, Stow, Ship-shape ! ! ! ! Sail trim ("turn & trim") ! ! ! ! Points of sail ! ! ! ! Demo the start, stop, and operation of motor ! ! ! ! Jibing ! ! ! ! Getting underway & return with motor ! ! ! ! Steering three ways (tiller, sails, wt. shift) ! ! ! ! Intro to mooring return Knot of the day--locking cleat hitch Knot of the day--figure 8 Debrief Debrief Highlights? No-go Zone Questions? Homework: points of sail On Has the wind changed? Shore Homework: Tacking Jibing 5 days -

FEATURED: MULTIHULL FLEET Summer Is Behind Us for the Year As We Approach Fall

AUSTIN YACHT CLUB TELLTALE September 2020 Sailing during Covid-19 Sail safe, stay healthy! Message from the Commodore Hopefully the heat of the FEATURED: MULTIHULL FLEET summer is behind us for the year as we approach fall. The City and County have recently moved from Covid Stage 4 Restrictions to Stage 3, and hopefully to Stage 2 soon. Unfortunately, given the orders from the City and County that limit gatherings, we have had to cancel the Annual Banquet for this year. Given the lack of sailing and other activity this year, we have also decided not to present most of the Annual Awards. In place of the Sailing Awards, we are asking for nominations for Special Service to the Club Awards for those who have gone above and beyond during this crazy year. Nominations can be submitted via the website. More details in this issue. The Board will review the nominations and make selections. However, take heart, the Blue Duck Award will be presented at the Annual Membership Meeting along with the Special Service Awards. The Blue Duck nomination form is also on the website. The Board is planning a couple of Covid-compliant regattas for the weekends of October 10th and 17th. See Vice Commodore Diane Covert’s column for more details. As of now, the Skippers meetings will be via Zoom before the regatta, and trophies acknowledged by Zoom afterwards. More details online and in this issue of the Telltale. Although we have had some much needed rain, not much of it has ended up in the lake, so look for dock moves starting very soon. -

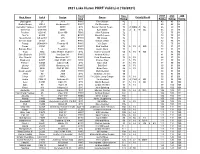

2021 Lake Huron PHRF Valid List (1/8/2021)

2021 Lake Huron PHRF Valid List (1/8/2021) Yacht Base PHRF ASM JAM Boat Name Sail # Design Owner Penalty/Credit Club Rating Rating Rating Rating Unplugged 25 J111 PHYC Tim Clayson 42 42 45 51 Gratiot Beach USA 6 Henderson 30 PHYC Ed Shumaker 45 45 48 54 Canadian Yankee CAN333 SR33 SYC Boston Racing Team 78 -3 MSG -9 SL 66 69 75 Girlfriend CAN 100 SR33 SYC Kyle Griffin 78 -3 E -9 SL 66 69 75 Resilient USA 40 Esse 850 TBYC Mike Ruhland 72 72 75 81 FireFly 40935 J35 BCYC Sheri Dufresne 72 72 75 81 Major Detail US 42763 J35 PHYC Bill Vogan 72 72 75 81 Steelin' Gold 25161 J35 PHYC William White 72 72 75 81 Rowdy USA42418 Thomas 35 PHYC Val Saph 72 72 75 81 Tango 83021 J40 PHYC Bob VanEck 75 6 FJ -3 MG 78 81 87 Banana Boat 2 Tremolino PHYC Austin Dunn 78 78 81 87 Tryst 3302 C&C 37/40 R Mod Keel SYC Robert Carswell 66 6 FJ 9 KE 81 84 90 Saint Barbara SK375 Van Dam 38 PHYC Andrew Kileley 81 81 84 90 War Chant 2 51793 Beneteay 36.7 PHYC Reid Stromberg 78 6 FJ 84 87 93 Daydream 44937 C&C 37/40+ WK SIYC Charles Saur 81 6 FJ 87 90 96 Falcon I 34843 C&C 41 CB SYC Dave Duff 81 6 FJ 87 90 96 Liberty 25656 Beneteau 42 PHYC Bob Bert 84 6 FJ 90 93 99 Stalwart 4295 C&C 41 WK PHYC Brian Cann 84 6 FJ 90 93 99 Good Lookin' 123 J105 PHYC Mark DenUyl 90 90 93 99 J 105 92 J105 SYC Christian Jensen 90 90 93 99 C Fun 15017 NA40 PHYC Phil, Dale, Jerry Conger 84 6 FJ 90 93 99 Jeans CAN 33 Andrews 30 SYC Tim Bechard 99 -3 CFR -3 RD 93 96 102 Iteru 54391 C&C 37+ SYC Martin Benson 81 6 FJ 6 KE 93 96 102 Epic 80 Hobie 33 SYC Jordan Stewart 93 6 FJ 99 102 108 Rebel 444 -

Series Drogue. See Later Discussion on Series Drogues

HEAVY WEATHER SAILING A paper for the OCC Forum (Editor’s Note: This paper was prepared by Tony Gooch based on lessons learned over 35 years and 160,000 miles of ocean sailing and with input from OCC members via the Forum. Tony and his wife, Coryn, have spent much time in high latitudes … Bering Sea, Labrador, Iceland, Svalbard, Chile, Antarctica and South Georgia. Tony has made two solo circumnavigations via the Southern Capes.) This paper is presented under the following headings: - Philosophy - Boat preparation - Keeping the boat watertight - Ability to ‘secure ship’ - Securing the crew - Before the storm - During the storm - Heavy weather sailing tactics - Heaving to - Lying a-hull - Speed limiting drogues - Parachutes (sea anchors) - Series drogue Philosophy With due regard to the seasons and with careful monitoring of forecast weather, most ocean passages, particularly in the mid- latitudes, can be made in winds that rarely exceed 25-30kn. Most often the heavy weather can be handled by heaving-to while the gale passes. However, it is probable that in a number of years of Copyright © 2015 by Ocean Cruising Club. All rights reserved. Terms & Conditions apply. 1 ocean sailing you will, at some time, run into stronger winds that will require different tactics. Although heavy weather can be uncomfortable, with good preparation and thorough knowledge of your boat, it is not something to be particularly worried about. Offshore sailing in heavy weather can best be described as the ‘art of waiting’. Assuming you have sea room, the best approach is to take it easy. There is no point in fighting the weather. -

J/22 Sailing MANUAL

J/22 Sailing MANUAL UCI SAILING PROGRAM Written by: Joyce Ibbetson Robert Koll Mary Thornton David Camerini Illustrations by: Sally Valarine and Knowlton Shore Copyright 2013 All Rights Reserved UCI J/22 Sailing Manual 2 Table of Contents 1. Introduction to the J/22 ......................................................... 3 How to use this manual ..................................................................... Background Information .................................................................... Getting to Know Your Boat ................................................................ Preparation and Rigging ..................................................................... 2. Sailing Well .......................................................................... 17 Points of Sail ....................................................................................... Skipper Responsibility ........................................................................ Basics of Sail Trim ............................................................................... Sailing Maneuvers .............................................................................. Sail Shape ........................................................................................... Understanding the Wind.................................................................... Weather and Lee Helm ...................................................................... Heavy Weather Sailing ......................................................................