Book Reviews 69 the Canadian Pacific Railway and The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rocky Mountain Express

ROCKY MOUNTAIN EXPRESS TEACHER’S GUIDE TABLE OF CONTENTS 3 A POSTCARD TO THE EDUCATOR 4 CHAPTER 1 ALL ABOARD! THE FILM 5 CHAPTER 2 THE NORTH AMERICAN DREAM REFLECTIONS ON THE RIBBON OF STEEL (CANADA AND U.S.A.) X CHAPTER 3 A RAILWAY JOURNEY EVOLUTION OF RAIL TRANSPORT X CHAPTER 4 THE LITTLE ENGINE THAT COULD THE MECHANICS OF THE RAILWAY AND TRAIN X CHAPTER 5 TALES, TRAGEDIES, AND TRIUMPHS THE RAILWAY AND ITS ENVIRONMENTAL CHALLENGES X CHAPTER 6 DO THE CHOO-CHOO A TRAIL OF INFLUENCE AND INSPIRATION X CHAPTER 7 ALONG THE RAILROAD TRACKS ACTIVITIES FOR THE TRAIN-MINDED 2 A POSTCARD TO THE EDUCATOR 1. Dear Educator, Welcome to our Teacher’s Guide, which has been prepared to help educators integrate the IMAX® motion picture ROCKY MOUNTAIN EXPRESS into school curriculums. We designed the guide in a manner that is accessible and flexible to any school educator. Feel free to work through the material in a linear fashion or in any order you find appropriate. Or concentrate on a particular chapter or activity based on your needs as a teacher. At the end of the guide, we have included activities that embrace a wide range of topics that can be developed and adapted to different class settings. The material, which is targeted at upper elementary grades, provides students the opportunity to explore, to think, to express, to interact, to appreciate, and to create. Happy discovery and bon voyage! Yours faithfully, Pietro L. Serapiglia Producer, Rocky Mountain Express 2. Moraine Lake and the Valley of the Ten Peaks, Banff National Park, Alberta 3 The Film The giant screen motion picture Rocky Mountain Express, shot with authentic 15/70 negative which guarantees astounding image fidelity, is produced and distributed by the Stephen Low Company for exhibition in IMAX® theaters and other giant screen theaters. -

Xmr^M. ALBERTA

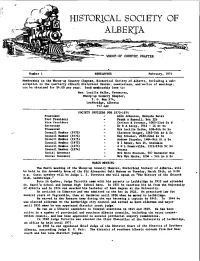

f C 4i;l, HISTORICAL SOCIETY OF (( xmr^m. ALBERTA WHOOP-UP COUNTRY. CHAPTER Number 1 NEWSLETTER February, 1974 Membership in the Whoop-up Country Chapter, Historical Society of Alberta, including a sub scription to the quarterly Alherta Histoviaal Review, newsletters, and'notice of meetings, can be obtained for $4.00 per year. Send membership fees to: Mrs. Lucille Dalke, Treasurer, Whoop-up Country Chapter, P. 0. Box 974, Lethbridge, Alberta TIJ 4A2 SOCIETY OFFICERS FOR 1973-1974 President Al&x Johnston, Marquis Hotel Past President Frank A Russell. Box 326 Vice President Carlton R Stewart, 1005-23rd St N Secretary Dr R A Lacey, 1912 - 14 St So Treasurer Mrs Lucille Dalke, 638-9th St So Council Member (1976) - Clarence Geiger, 1265-5th Av A So Council Member (1976) - Ray Schuler, 2630-22nd Av So Council Member (1975) - Andrew Staysko, 1404-9th St A So Council Member (1975) - R I Baker, Box 14, Coaldale Council Member (1974) - A H L Somerville, 1312-15th St So Council Member (1974) - Vacant Social Convener Mrs Nora Everson, 507 Balmoral Hse Social Convenor Mrs Wyn Myers, 1236 - 5th Av A So MARCH MEETING The March meeting of the Whoop-up Country Chapter, Historical Society of Alberta, will be held in the Assembly Room of the Sir Alexander Gait Museum on Tuesday, March 26th, at 8:00 p.m. Guest speaker will be Judge L. S. Turcotte who will speak on "The History of the Chinook Club, Lethbridge." Born in Quebec, Judge Turcotte came with his parents to Lethbridge in 1912 and attended St, Basil's School and Bowman High School here. -

Alberta Coal Studies Messrs

Alex Johnston Keith G. Gladwyn L. Gregory Ellis LETHBRIDGE ITS COAL INDUSTRY Copyright © 19Sy by the City of Lethbridge. Crown cop\ right re^er\ ed No part of this book m:\\ be reproduced or tran.smitted in an\' form or by an\' mean.s, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, or by any information .storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. ISBN - 0-919224-81-4 Printed and bound in Canada By Graphcom Printers Ltd., Lethbridge, Alberta Cartography b\ Energy Resources Conservation Board Canadian Cataloguing in Publication Data Johnston, A. (Alex), 1920- Lethbridge, its coal industry (Occasional paper ; no. 20) Bibliography: p. 139-143 Includes inde.x. 1 Coal mines and mining - Alberta - Lethbridge - History. I. Cladwvn. Keith G. n. Ellis, L. Gregory (Leonard Gregory). III. Lethbridge Historical .Society, I\'. Title. \'. .Series: Occasional paper (Lethbridge Historical Society) ; no. 2(). Hl»SS4,C23A-t4 1989 33.S.2'~24'()9-123-i C.SS-()914.S-t-X A product of: The George and Jessie Watson Memorial Computer Centre Sir Alexander Gait Museum, Lethbridge, Alberta LETHBRIDGE: ITS COfiL INDUSTRY by Alex Johnston Sir Alexander Gait Museum, Lethbridge, Alberta Keith G. Gladwyn Energy Resources Conservation Board, Calgary, Alberta L. Gregory Ellis Sir Alexander Gait Museum, Lethbridge, Alberta Occasional Paper No. 20 The Lethbridge Historical ,Societ\ P. O. Bo.x 9-4 Lethbridge, Alberta TIJ 4A2 1989 Dr Ck'orge Mencr Dawson (thirdfrom left) was the son ofSirJol.w town of Dawson, Yukon Territory. He was GSC director from 1895 William Dawson, principal of McC!ill Vnirersily He was burn in to 1901. -

NEWSLETTER Lethbridge Historical Society the Southern Alberta Chapter of the Historical Society of Alberta

NEWSLETTER Lethbridge Historical Society The Southern Alberta Chapter of the Historical Society of Alberta P.O.BOX 974 Lethbridge, Alberta, Canada TIJ 4A2 ®Copvtiahl1999_ INumba-l NbWt^Lfc 11 bti ISSN 0836-724^ Membership in the Historical Society of Alberta is $25.00 per year single or $30.00 a couple or family. It includes a subscription to the quarterly ALBERTA HISTORY, and members residing from Nanton south are also registered with the Lethbridge Historical Society and receive newsletters and notices. (Your mailing label expiration date will be highlighted when it is time to renew) Please send dues to the treasurer. LETHBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS Presktent Carlton R. (Barbara) Stewart Vtoe& Past President Wm. (Bill) (Juanita) Ungard Seaetary/Newsletter Editor Irma (Jake) Dogterom Treasurer David J. (Gerry) Dowey Council Member (1999 Richard Shockley (Leslie) Council Member (1999 Helen Kovacs Council Member (2000 Ernie (Goldie) Snowden Council Member (20CX» R. W. (Dick) (Theresa) Papworth Council Member (2001 AudreySwedish Council Member (20011 Robert (Emerice) Shore Book Distribution & Sales Ralph Erdman ^ Regular meetings are held in the Theatre Gallery of the Lethbridge Public Library at 7:15 p.m. on the fourth Tuesday of the month. Notices From the executive meeting minutes: The annual meeting was held November 24 in the Suggested guidehnes for memorials for deceased Theatre Gallery of the Lethbridge Public Library. The members have been compiled as follows: new officers are noted above. 1. Such donations to be determined by the executive with The following notice of motion was made at the approval from the membership. meeting: "/ move the following Notice Of Motion to all members at large of the Lethbridge Historical Society. -

From the Frontier to the Front: Imagined Community and the Southwestern Alberta Great War Experience

FROM THE FRONTIER TO THE FRONT: IMAGINED COMMUNITY AND THE SOUTHWESTERN ALBERTA GREAT WAR EXPERIENCE BRETT CLIFTON Bachelor of Arts, Canadian Studies, University of Lethbridge, 2013 Bachelor of Education, Social Studies Education, University of Lethbridge, 2013 A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies Of the University of Lethbridge In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements of the Degree MASTER OF ARTS Department of History University of Lethbridge, LETHBRIDGE, ALBERTA CANADA © Brett Clifton, 2016 FROM THE FRONTIER TO THE FRONT: IMAGINED COMMUNITY AND THE SOUTHWESTERN ALBERTA GREAT WAR EXPERIENCE BRETT CLIFTON Date of Defence: December 16, 2016 Dr. Heidi MacDonald Associate Professor Ph.D. Thesis Supervisor Dr. Amy Shaw Associate Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Dr. Jeff Keshen Adjunct Professor Ph.D. Thesis Examination Committee Member Mount Royal University Calgary, Alberta Dr. Christopher Burton Associate Professor Ph.D. Chair, Thesis Examination Committee Dedication This thesis is dedicated to my mother, Carol, without whom none of this would have been possible. Thanks Mom. iii Abstract As Canada joins other nations in observing a succession of First World War centenaries, the public narrative constructed over the past hundred years holds up the Great War, particularly the battle for Vimy Ridge, as a pivotal point in Canadian history that forged our national identity. This thesis sets aside this romanticised and idealised construct, focusing upon the regional and cultural variations specific to Lethbridge and Southwestern Alberta. While much work has been done on the French-English divide, comparatively few microstudies have examined the distinctive experiences and regional nuances of other communities within this vast and diverse nation. -

Proquest Dissertations

THE LANGUAGE OF MAKING: THE FINE ARTS, CRAFTS, AND BUILDING TRADES by David J. Cocks Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Architecture at Dalhousie University Halifax, Nova Scotia April 2010 © Copyright by David J. Cocks, 2010 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON MAOISM Ottawa ON K1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-68067-4 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-68067-4 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduce, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent §tre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

Vital Signs 2019 Alberta Is a Canada Revenue Agency-Registered Charity and the Ninth-Oldest of Canada’S 191 Community Foundations

2019 COMMUNITY HEALTHY ENVIRONMENT LIVING CULTURAL LIFE LIFELONG CONNECTIONS COMMUNITIES STANDARDS LEARNING 1 About the Community Foundation The Community Foundation of Lethbridge and Southwestern Vital Signs 2019 Alberta is a Canada Revenue Agency-registered charity and the ninth-oldest of Canada’s 191 community foundations. All gifts to the Community Foundation are endowed, and the investment income generated is distributed to qualified groups throughout What is Vital Signs? Southwestern Alberta. In 2018, the Community Foundation supported the community with over $850,000 in grant funding. Vital Signs is a community check-up conducted by community Learn more at www.cflsa.ca. foundations across Canada that measures the vitality of our region and identifies significant trends in a range of Community Foundation Board of Directors areas critical to quality of life. Vital Signs is coordinated nationally by Community Foundations of Canada. Randall Baker, President (Pincher Creek) The Community Foundation of Lethbridge and Southwestern Alberta has published Vital Signs reports since 2013. In addition to informing donors of areas of need in the community, it has Steve Miles, Vice-President (Lethbridge) grown into a tool that helps to determine the allocation of financial support through granting initiatives. Applicants to the Bruce Anderson, Second Vice-President (Lethbridge) Community Foundation’s Community Priorities and Henry S. Varley Fund for Rural Life granting programs must indicate how Darren Adamson, Treasurer (Lethbridge) their proposed project addresses areas of need by identifying within which of the six Impact Areas their project fits. Vital Signs is a tool to spark dialogue. The information Bjorn Berg, Director (Pincher Creek) presented in this report is a quick look at bigger topics—use Vital Signs as a starting point to initiate conversations and learn more. -

Canadian Rail No269 1974

Rail SHOVEL ON A LITTLE MORE COAL! Colin J. Churcher ,.' hould you ever decide to join the Railway Branch, Surface Iransport Administration, S Department of Transport, Government of Canada, you can expect to become involved in a variety of undertakings, most of which are related to a greater or lesser de gree to railways. But who could have imagined that an apparently innocent tele- phone call in mid-April 1973 would have projected me into the steam locomotive procurement and operation business? It was unb~lievable, but it was a fact. A steam locomotive was required for operation in the Ottawa, Canada area by July 1, 1973 and I was expected to pro cure it. When I became involved, the terminal date was about 75 days away. I n the early 1970s, steam locomotives were like gold: precious and scarce. But there were and are a number of diligent modern-day prospectors like Mr. Duncan du Fresne of the Air Traffic Control Section, Air Administration, Department of Transport. You might think that a person working for Air Traffic Control would not know anything about railways but, in Dunc's case, the exoct opposite is the case. Dunc could tell me that a group in Toronto had an opera- ting steam engine, which just might be available for the proposed Ottawa operation. Taking a chance, I made a telephone call and, within a short time, I had determined that Ontario Rail Association did have an ex-Canadian Pacific Railway 4-6-0 Locomotive, Number 1057, which was available for the summer season. -

Canadian Rail No517 2007

Published bi-monthly by the Canadian Railroad Historical Association Publie tous les deux mois par l'Association Canadienne d'Histoire Ferroviaire 42 ISSN 0008-4875 CANADIAN RAIL Postal Permit No. 40066621 PUBLISHED BI-MONTHLY BY THE CANADIAN RAILROAD HISTORICAL ASSOCIATION TABLE OF CONTENTS The 2141 'Spirit of Kamloops', David Emmington ... ... _____ .. __ . _... __ . ___ . _. _.... ..... _....... __ ... __ . .. 43 Book Reviews ...... ....... _. .... .... _. _..... _.. ... ................ .. ... _. _............ _... 51 Six October Days behind 2816, Fred Angus ...... .. .... ... ___ ....... ... ... ...... ............. .. .. _...... 56 2816 Is the Star of 'Rocky Mountain Express', Peter Murphy . ................. ........... ....... ... _. ... _.. .. 67 Business Car ........... ... ............................................. .... .................. .......... 70 FRONT COVER: Russ Watson caught ex CNR 2141 at Campbell Creek on September 24, 2005 just prior to the start ofthe Almstrong Explorer trips. BELOW: Volunteers prepare ex-CNR 2141 for removal from Riverside Park in 1994. Photo cowtesy the Kamloops Heritage Railway Society. For your membership in the CRHA, which Canadian Rail is continually in need of news, stories, EDITOR: Fred F. Angus includes a subscription to Canadian Rail, historical data, photos, maps and other material. CO-EDITORS: Douglas N.W. Smith, write to: Please send all contributions to the editor: Fred F. Peter Murphy CRHA, 110 Rue St-Pierre, St. Constant, Angus, 3021 Trafalgar Avenue, Montreal, P'Q. ASSOCIATE EDITOR (Motive Power): Que. J5A 1G7 H3Y 1H3, e-mail [email protected] . No payment can Hugues W. Bonin be made for contributions, but the contributer will be Membership Dues for 2007: LAYOUT: Gary McMinn given credit for material submitted. Material will be In Canada: $45.00 (including all taxes) returned to the contributer if requested. -

LETHBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY the LETHBRIDGE CHAPTER of the Historical Society of Alberta

LETHBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY THE LETHBRIDGE CHAPTER Of the Historical Society of Alberta 3«fe_. P.O. BOX 974 LETHBRIDGE. ALBERTA. TIJ 4A2 e Copyright 1993 fstfTterl NEWSLETTER ISSN 0638-7249 January 1993 Membership in the Historical Society of Alberta, including a subscription to the quarterly ALBERTA HISTORY: $20.00 per year single $25.00 a couple or family. Those members residing from Nanton south are also registered with the Lethbridge Historical Society and receive newsletters and notices. Your mailing label expiration date will be highlighted when it is time to renew) Please send your dues to the treasurer. LETHBRIDGE HISTORICAL SOCIETY OFFICERS FOR 1992 President George F. Kush Past President Douglas J. Card Vice-President Wm. (Bill) Lingard Secretary/Newsletter Editor Irma Dogterom Treasurer David J. Dowey Council Member (1995) Kathleen E. Miller Council Member (1995) Robert Shore Council Member (1994) Ralph Erdman Council Member (1994) Carlton R. Stewart Council Member (1993) Beatrice Hales Coundi Member (1993) Nora Holmes Regular meetings are held in the Theatre Gallery of the Lethbridge Public Library at 7:15 p.m. on the fourth Tuesday of the month. Notices HIGH LEVEL BRIDGE The next regular meeting of the Lethbridge Historical Society will PHOTO CHALLENGE be held on January 26, 1993. The program will have George Kush, speaking on "Across the Medicine Line. Sitting Bull and The LHS Book Publishing Committee is contemplating the N.W.M.P." reprinting an updated version of C.P. Rail High Level Bridge at Lethbridge - by Alex Johnston, it was our 1976 publication Gordon Toiton will give a talk at the February 23,1993 meeting. -

Nicholas Morant Fonds (M300 / S20 / V500)

NICHOLAS MORANT FONDS (M300 / S20 / V500) I. PHOTOGRAPHY SERIES : A. NEGATIVES AND TRANSPARENCIES 1. Darkroom files : c. Colour (V500 / A4 / 2 to 528; V500 / A5 / Z1 to Z1013) 2. Okanagan Valley orchards. -- 1948. -- 8 photographs : transparencies, col, 7.5x10cm. -- Geographic region: British Columbia. -- Storage location: V500/A4/2. 3. Threemaster, City of New York, Minas Basin, 1938. -- 1938. -- 2 photographs : transparencies, col, 7.5x10cm. -- Ship. -- Geographic region: Nova Scotia. -- Storage location: V500/A4/3. 4. Boxcar loading grain at Crowfoot, AB. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 12 photographs (5 negatives, 7 transparencies) : col, 6x6cm. -- Prairie scenes, Canadian Pacific Railway. -- Negatives, film. -- NM note: see BW H-23. -- Geographic region: Alberta. -- Storage location: V500/A4/4. 5. Nova Scotian misty morning. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 1 photograph : transparency, col, 7.5x10cm. -- Geographic region: Nova Scotia. -- Storage location: V500/A4/5. 6. Loading pulpwood (Ontario) Martin. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- NM note: see also Z-914. -- Empty file 7. Electric shovel, Forestburg Alta. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 10 photographs (6 negatives, 4 transparencies) : col, 6x6cm. -- Negatives, film. -- Geographic region: Alberta. -- Storage location: V500/A4/7. 8. Nova Scotian shipmodeller. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 1 photograph : negative, film, col. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -- Geographic region: Nova Scotia. -- Storage location: V500/A4/8. 9. Kicking Horse River, Mt Field. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 1 photograph : transparency, col, 7.5x10cm. -- Yoho National Park BC. -- Geographic region: British Columbia. -- Storage location: V500/A4/9. 10. Teepee interior, Stoney's, Mrs. Nat Hunter. -- [between 1930 and 1980]. -- 4 photographs : negatives, film, col. -- Stoney First Nation. -- 7.5x10cm or smaller. -

Welcome to Bridge by the Bridge Events Food Service Tours

Tuesday, February 24, 2009 CBF Bridge by the Bridge Regional Issue 1 Welcome to Bridge by the Bridge the Canon camera hanging around her neck), When a member of our High Level Bridge ask the folks at hospitality, ask any of the Centennial Committee asked if I might be local group who will be wearing an able to organize a bridge (the game) event to identifying tag. If you need a ride or celebrate the bridge (the structure), I hoped information about where to shop, just ask. to get a national event sanctioned by the ACBL. However, Jan Anderson of the Thank you so much for attending Canadian Bridge Federation was not Bridge by the Bridge, the 2009 CBF particularly encouraging. Bridge Week was Regional. already set. The one regional that the CBF had been allocated as a fundraiser for the international fund was slated to be in Events Toronto. Despite that, I went forward with Monday, February 23 an “Expression of Interest”. Charity Pairs 7 pm Long story short - Southern Ontario turned Open Knockouts (Rd. 1) 7 pm out to be REALLY expensive. The event Tuesday, February 24th needs to make money so we can support our Morning Side Game Pairs 1 8:45 am best players in world class events. So it Opening Knockouts cont. (Rds. 8:45 am, didn’t take long for the CBF Board to turn 2, 3 & 4) 1 pm & down the Toronto option and call me. 7 pm Initially, I could not find an appropriate Compact Knockouts 1 & 7 pm venue. I was on the verge of telling the CBF that I could not find a site for the dates they Stratified 199er pairs (singles) 1 & 7 pm had available.