Psych 458 Syllabus

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Task-Based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information Visualization

A Task-based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information Visualization Evanthia Dimara, Steven Franconeri, Catherine Plaisant, Anastasia Bezerianos, and Pierre Dragicevic Three kinds of limitations The Computer The Display 2 Three kinds of limitations The Computer The Display The Human 3 Three kinds of limitations: humans • Human vision ️ has limitations • Human reasoning 易 has limitations The Human 4 ️Perceptual bias Magnitude estimation 5 ️Perceptual bias Magnitude estimation Color perception 6 易 Cognitive bias Behaviors when humans consistently behave irrationally Pohl’s criteria distilled: • Are predictable and consistent • People are unaware they’re doing them • Are not misunderstandings 7 Ambiguity effect, Anchoring or focalism, Anthropocentric thinking, Anthropomorphism or personification, Attentional bias, Attribute substitution, Automation bias, Availability heuristic, Availability cascade, Backfire effect, Bandwagon effect, Base rate fallacy or Base rate neglect, Belief bias, Ben Franklin effect, Berkson's paradox, Bias blind spot, Choice-supportive bias, Clustering illusion, Compassion fade, Confirmation bias, Congruence bias, Conjunction fallacy, Conservatism (belief revision), Continued influence effect, Contrast effect, Courtesy bias, Curse of knowledge, Declinism, Decoy effect, Default effect, Denomination effect, Disposition effect, Distinction bias, Dread aversion, Dunning–Kruger effect, Duration neglect, Empathy gap, End-of-history illusion, Endowment effect, Exaggerated expectation, Experimenter's or expectation bias, -

Safe-To-Fail Probe Has…

Liz Keogh [email protected] If a project has no risks, don’t do it. @lunivore The Innovaon Cycle Spoilers Differentiators Commodities Build on Cynefin Complex Complicated sense, probe, analyze, sense, respond respond Obvious Chaotic sense, act, categorize, sense, respond respond With thanks to David Snowden and Cognitive Edge EsBmang Complexity 5. Nobody has ever done it before 4. Someone outside the org has done it before (probably a compeBtor) 3. Someone in the company has done it before 2. Someone in the team has done it before 1. We all know how to do it. Esmang Complexity 5 4 3 Analyze Probe (Break it down) (Try it out) 2 1 Fractal beauty Feature Scenario Goal Capability Story Feature Scenario Vision Story Goal Code Capability Feature Code Code Scenario Goal A Real ProjectWhoops, Don’t need forgot this… Can’t remember Feature what this Scenario was for… Goal Capability Story Feature Scenario Vision Story Goal Code Capability Feature Code Code Scenario Goal Oops, didn’t know about Look what I that… found! A Real ProjectWhoops, Don’t need forgot this… Can’t remember Um Feature what this Scenario was for… Goal Oh! Capability Hmm! Story FeatureOoh, look! Scenario Vision Story GoalThat’s Code funny! Capability Feature Code Er… Code Scenario Dammit! Oops! Oh F… InteresBng! Goal Sh..! Oops, didn’t know about Look what I that… found! We are uncovering be^er ways of developing so_ware by doing it Feature Scenario Goal Capability Story Feature Scenario Vision Story Goal Code Capability Feature Code Code Scenario Goal We’re discovering how to -

Infographic I.10

The Digital Health Revolution: Leaving No One Behind The global AI in healthcare market is growing fast, with an expected increase from $4.9 billion in 2020 to $45.2 billion by 2026. There are new solutions introduced every day that address all areas: from clinical care and diagnosis, to remote patient monitoring to EHR support, and beyond. But, AI is still relatively new to the industry, and it can be difficult to determine which solutions can actually make a difference in care delivery and business operations. 59 Jan 2021 % of Americans believe returning Jan-June 2019 to pre-coronavirus life poses a risk to health and well being. 11 41 % % ...expect it will take at least 6 The pandemic has greatly increased the 65 months before things get number of US adults reporting depression % back to normal (updated April and/or anxiety.5 2021).4 Up to of consumers now interested in telehealth going forward. $250B 76 57% of providers view telehealth more of current US healthcare spend % favorably than they did before COVID-19.7 could potentially be virtualized.6 The dramatic increase in of Medicare primary care visits the conducted through 90% $3.5T telehealth has shown longevity, with rates in annual U.S. health expenditures are for people with chronic and mental health conditions. since April 2020 0.1 43.5 leveling off % % Most of these can be prevented by simple around 30%.8 lifestyle changes and regular health screenings9 Feb. 2020 Apr. 2020 OCCAM’S RAZOR • CONJUNCTION FALLACY • DELMORE EFFECT • LAW OF TRIVIALITY • COGNITIVE FLUENCY • BELIEF BIAS • INFORMATION BIAS Digital health ecosystems are transforming• AMBIGUITY BIAS • STATUS medicineQUO BIAS • SOCIAL COMPARISONfrom BIASa rea• DECOYctive EFFECT • REACTANCEdiscipline, • REVERSE PSYCHOLOGY • SYSTEM JUSTIFICATION • BACKFIRE EFFECT • ENDOWMENT EFFECT • PROCESSING DIFFICULTY EFFECT • PSEUDOCERTAINTY EFFECT • DISPOSITION becoming precise, preventive,EFFECT • ZERO-RISK personalized, BIAS • UNIT BIAS • IKEA EFFECT and • LOSS AVERSION participatory. -

John Collins, President, Forensic Foundations Group

On Bias in Forensic Science National Commission on Forensic Science – May 12, 2014 56-year-old Vatsala Thakkar was a doctor in India but took a job as a convenience store cashier to help pay family expenses. She was stabbed to death outside her store trying to thwart a theft in November 2008. Bloody Footwear Impression Bloody Tire Impression What was the threat? 1. We failed to ask ourselves if this was a footwear impression. 2. The appearance of the impression combined with the investigator’s interpretation created prejudice. The accuracy of our analysis became threatened by our prejudice. Types of Cognitive Bias Available at: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/List_of_cognitive_biases | Accessed on April 14, 2014 Anchoring or focalism Hindsight bias Pseudocertainty effect Illusory superiority Levels-of-processing effect Attentional bias Hostile media effect Reactance Ingroup bias List-length effect Availability heuristic Hot-hand fallacy Reactive devaluation Just-world phenomenon Misinformation effect Availability cascade Hyperbolic discounting Recency illusion Moral luck Modality effect Backfire effect Identifiable victim effect Restraint bias Naive cynicism Mood-congruent memory bias Bandwagon effect Illusion of control Rhyme as reason effect Naïve realism Next-in-line effect Base rate fallacy or base rate neglect Illusion of validity Risk compensation / Peltzman effect Outgroup homogeneity bias Part-list cueing effect Belief bias Illusory correlation Selective perception Projection bias Peak-end rule Bias blind spot Impact bias Semmelweis -

Dear Friends and Colleagues

Dear friends and colleagues On behalf of the organizational team, it is our pleasure to extend a warm welcome to all of you. We hope that you are ready for the stimulating and exciting academic experience of the 16th General Meeting of the European Association of Social Psychology. We received a total of 960 submissions this year representing more than 40 countries. This reflects roughly 1200 presentations within symposia, thematic sessions, and as posters, and constitutes a 34% increase relative to the last General Meeting. The program committee has worked with great dedication to organize an exciting program on the basis of these worldwide contributions. The scientific program includes 11 parallel sessions with 90 symposia, 63 thematic sessions, four large poster sessions (one each day), awards session and the Tajfel lecture. Moreover, round-table discussions will be held by some of our most prominent colleagues during lunch breaks. The scientific program will start on Wednesday at 9:30, and will occupy most of Wednesday, Thursday, and Saturday, while Friday will only have scientific sessions during the morning. Friday afternoon will be dedicated to the awards session including the Tajfel lecture, and the business meeting. It is our hope that the program will serve as an invitation to many fruitful discussions yielding valuable insights about all topics in our field and about social psychology at large. An international, scientific meeting should also provide opportunities for collaborative meetings and social interactions between friends and colleagues, outside the scientific program. We have organised a social programme which we hope will provide good opportunities to renew old friendships and to make new ones. -

To Err Is Human, but Smaller Funds Can Succeed by Mitigating Cognitive Bias

FEATURE | SMALLER FUNDS CAN SUCCEED BY MITIGATING COGNITIVE BIAS To Err Is Human, but Smaller Funds Can Succeed by Mitigating Cognitive Bias By Bruce Curwood, CIMA®, CFA® he evolution of investment manage 2. 2000–2008: Acknowledgement, where Diversification meant simply expanding the ment has been a long and painful plan sponsors discovered the real portfolio beyond domestic markets into T experience for many institutional meaning of risk. lesscorrelated foreign equities and return plan sponsors. It’s been trial by fire and 3. Post2009: Action, which resulted in a was a simple function of increasing the risk learning important lessons the hard way, risk revolution. (more equity, increased leverage, greater generally from past mistakes. However, foreign currency exposure, etc.). After all, “risk” doesn’t have to be a fourletter word Before 2000, modern portfolio theory, history seemed to show that equities and (!@#$). In fact, in case you haven’t noticed, which was developed in the 1950s and excessive risk taking outperformed over the there is currently a revolution going on 1960s, was firmly entrenched in academia long term. In short, the crux of the problem in our industry. Most mega funds (those but not as well understood by practitioners, was the inequitable amount of time and wellgoverned funds in excess of $10 billion whose focus was largely on optimizing effort that investors spent on return over under management) already have moved return. The efficient market hypothesis pre risk, and that correlation and causality were to a more comprehensive risk management vailed along with the rationality of man, supposedly closely linked. -

Thinking About Thinking: Cognition, Science, and Psychotherapy

THINKING ABOUT THINKING This book examines cognition with a broad and comprehensive approach. Draw- ing upon the work of many researchers, McDowell applies current scientific thinking to enhance the understanding of psychotherapy and other contemporary topics, including economics and health care. Through the use of practical exam- ples, his analysis is accessible to a wide range of readers. In particular, clinicians, physicians, and mental health professionals will learn more about the thought processes through which they and their patients assess information. Philip E. McDowell , LCSW, has a private practice in Lowville, New York. He earned a Lifetime Achievement Award from the New York State Office of Mental Health in 2002. This page intentionally left blank THINKING ABOUT THINKING Cognition, Science, and Psychotherapy Philip E. McDowell First published 2015 by Routledge 711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 and by Routledge 27 Church Road, Hove, East Sussex BN3 2FA Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business © 2015 Taylor & Francis The right of Philip E. McDowell to be identified as author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with sections 77 and 78 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. Trademark notice : Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe. -

The Restraint Bias: How Much Control Do You Really Have? by Stan Clark - Senior Investment Advisor

An excerpt from “Perspectives” - Volume 6 - Issue 12 Behavioral finance The Restraint Bias: How much control do you really have? By Stan Clark - Senior Investment Advisor In an episode of the classic TV show Seinfeld, Jerry follows In one study, researchers asked students both arriving at and George’s hot stock tip and buys some shares. George tells leaving a cafeteria to rate a number of snacks, from least Jerry to be patient. The ever-confident Jerry is sure he can. desirable to most. They then asked the students to select one of But the stock is slow to develop. Jerry starts obsessively the snacks but not to eat it. The researchers told the students reading the daily stock market reports, wincing every time that if they brought the snack back in two weeks, they would he sees the stock drop another point or two. (Today, he receive a desirable reward. would have been checking online every few minutes!) Finally, in a panic, Jerry sells, losing more than half his Hungry students entering the cafeteria tended to pick a less money. A day or two later, George reports that the stock desirable snack to avoid the temptation to eat it right away. But is soaring. students leaving the cafeteria after a meal felt they could easily resist any snack because they were no longer hungry. So, they tended to confidently choose one of their favourite snacks. Guess I’d like to discuss the restraint bias – and how much control we which group resisted temptation best and exchanged their snacks really have over our urges. -

Taxonomies of Cognitive Bias How They Built

Three kinds of limitations Three kinds of limitations Three kinds of limitations: humans A Task-based Taxonomy of Cognitive Biases for Information • Human vision ️ has Visualization limitations Evanthia Dimara, Steven Franconeri, Catherine Plaisant, Anastasia • 易 Bezerianos, and Pierre Dragicevic Human reasoning has limitations The Computer The Display The Computer The Display The Human The Human 2 3 4 Ambiguity effect, Anchoring or focalism, Anthropocentric thinking, Anthropomorphism or personification, Attentional bias, Attribute substitution, Automation bias, Availability heuristic, Availability cascade, Backfire effect, Bandwagon effect, Base rate fallacy or Base rate neglect, Belief bias, Ben Franklin effect, Berkson's ️Perceptual bias ️Perceptual bias 易 Cognitive bias paradox, Bias blind spot, Choice-supportive bias, Clustering illusion, Compassion fade, Confirmation bias, Congruence bias, Conjunction fallacy, Conservatism (belief revision), Continued influence effect, Contrast effect, Courtesy bias, Curse of knowledge, Declinism, Decoy effect, Default effect, Denomination effect, Magnitude estimation Magnitude estimation Color perception Behaviors when humans Disposition effect, Distinction bias, Dread aversion, Dunning–Kruger effect, Duration neglect, Empathy gap, End-of-history illusion, Endowment effect, Exaggerated expectation, Experimenter's or expectation bias, consistently behave irrationally Focusing effect, Forer effect or Barnum effect, Form function attribution bias, Framing effect, Frequency illusion or Baader–Meinhof -

Social Bias Cheat Sheet.Pages

COGNITIVE & SOCIAL BIAS CHEAT SHEET Four problems that biases help us address: Problem 1: Too much information. There is just too much information in the world, we have no choice but to filter almost all of it out. Our brain uses a few simple tricks to pick out the bits of information that are most likely going to be useful in some way. We notice flaws in others more easily than flaws in ourselves. Yes, before you see this entire article as a list of quirks that compromise how other people think, realize that you are also subject to these biases. See: Bias blind spot, Naïve cynicism, Naïve realism CONSEQUENCE: We don’t see everything. Problem 2: Not enough meaning. The world is very confusing, and we end up only seeing a tiny sliver of it, but we need to make some sense of it in order to survive. Once the reduced stream of information comes in, we connect the dots, fill in the gaps with stuff we already think we know, and update our mental models of the world. We fill in characteristics from stereotypes, generalities, and prior histories whenever there are new specific instances or gaps in information. When we have partial information about a specific thing that belongs to a group of things we are pretty familiar with, our brain has no problem filling in the gaps with best guesses or what other trusted sources provide. Conveniently, we then forget which parts were real and which were filled in. See: Group attribution error, Ultimate attribution error, Stereotyping, Essentialism, Functional fixedness, Moral credential effect, Just-world hypothesis, Argument from fallacy, Authority bias, Automation bias, Bandwagon effect, Placebo effect We imagine things and people we’re familiar with or fond of as better than things and people we aren’t familiar with or fond of. -

List of Cognitive Biases

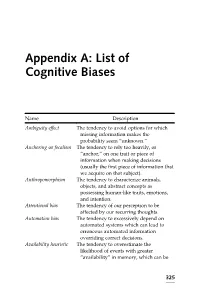

Appendix A: List of Cognitive Biases Name Description Ambiguity effect The tendency to avoid options for which missing information makes the probability seem “unknown.” Anchoring or focalism The tendency to rely too heavily, or “anchor,” on one trait or piece of information when making decisions (usually the first piece of information that we acquire on that subject). Anthropomorphism The tendency to characterize animals, objects, and abstract concepts as possessing human-like traits, emotions, and intention. Attentional bias The tendency of our perception to be affected by our recurring thoughts. Automation bias The tendency to excessively depend on automated systems which can lead to erroneous automated information overriding correct decisions. Availability heuristic The tendency to overestimate the likelihood of events with greater “availability” in memory, which can be 325 Appendix A: (Continued ) Name Description influenced by how recent the memories are or how unusual or emotionally charged they may be. Availability cascade A self-reinforcing process in which a collective belief gains more and more plausibility through its increasing repetition in public discourse (or “repeat something long enough and it will become true”). Backfire effect When people react to disconfirming evidence by strengthening their belief. Bandwagon effect The tendency to do (or believe) things because many other people do (or believe) the same. Related to groupthink and herd behavior. Base rate fallacy or The tendency to ignore base rate Base rate neglect information (generic, general information) and focus on specific information (information only pertaining to a certain case). Belief bias An effect where someone’s evaluation of the logical strength of an argument is biased by the believability of the conclusion. -

Selective Exposure Theory Twelve Wikipedia Articles

Selective Exposure Theory Twelve Wikipedia Articles PDF generated using the open source mwlib toolkit. See http://code.pediapress.com/ for more information. PDF generated at: Wed, 05 Oct 2011 06:39:52 UTC Contents Articles Selective exposure theory 1 Selective perception 5 Selective retention 6 Cognitive dissonance 6 Leon Festinger 14 Social comparison theory 16 Mood management theory 18 Valence (psychology) 20 Empathy 21 Confirmation bias 34 Placebo 50 List of cognitive biases 69 References Article Sources and Contributors 77 Image Sources, Licenses and Contributors 79 Article Licenses License 80 Selective exposure theory 1 Selective exposure theory Selective exposure theory is a theory of communication, positing that individuals prefer exposure to arguments supporting their position over those supporting other positions. As media consumers have more choices to expose themselves to selected medium and media contents with which they agree, they tend to select content that confirms their own ideas and avoid information that argues against their opinion. People don’t want to be told that they are wrong and they do not want their ideas to be challenged either. Therefore, they select different media outlets that agree with their opinions so they do not come in contact with this form of dissonance. Furthermore, these people will select the media sources that agree with their opinions and attitudes on different subjects and then only follow those programs. "It is crucial that communication scholars arrive at a more comprehensive and deeper understanding of consumer selectivity if we are to have any hope of mastering entertainment theory in the next iteration of the information age.