The Natural Place for the Play’

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Recollections and Reflections, a Professional Autobiography

... • . .... (fcl fa Presented to the LIBRARY of the UNIVERSITY OF TORONTO from the estate of MARION WALKER RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS. RECOLLECTIONS AND REFLECTIONS OF J. E. PLANCHE, (somerset herald). ^ |]rofcssiona( gaifobbcjrapbtr. " I ran it through, even from my boyish days, To the very moment that he bade me tell it." Othello, Act i., Scene 3. IN TWO VOLUMES. VOL. II. LONDON: TINSLEY BROTHERS, 18, CATHERINE STREET, STRAND. 1872. ..4^ rights reserved. LONDON BRADBURV, EVANS, AND CO., PRINTERS, WHITBFRIAR,-!. ——— CONTENTS. CHAPTER I. VAGK Another Mission to Paris—Production of " Le Domino Noir"— Mr. and Mrs. Charles Gore—Dinner at Lord Lyndhurst's Mons. Allou, Vice-President of the Society of Antiquaries of France—The Duke D'Istrie and his Collection of Armour Her Majesty's Coronation—" Royal Records "—Extension of Licence to the Olympic and Adelphi Theatres—" The Drama's Levee"—Trip to Calais with Madame Yestris and Charles Mathews previous to their departure for America—Visit to Tournehem—Sketching Excursion with Charles Mathews Marriage of Madame Vestris and Charles Mathews—They sail for New York—The Olympic Theatre opened under my Direc- tion—Farren and Mrs. Nisbett engaged—Unexpected return of Mr. and Mrs. Mathews—Re-appearance of the latter in " Blue Beard "— " Faint Heart never won Fair Lady "—"The Garrick Fever"—Charles Mathews takes Covent Garden Theatre CHAPTER II. Death of Haynes Bayly—Benefit at Drury Lane for his Widow and Family—Letters respecting it from Theodore Hook and Mrs. Charles Gore—Fortunate Results of the Benefit—Tho Honourable Edmund Byng—Annual Dinner established by him in aid of Thomas Dibdin—Mr. -

Teacher Resource Pack I, Malvolio

TEACHER RESOURCE PACK I, MALVOLIO WRITTEN & PERFORMED BY TIM CROUCH RESOURCES WRITTEN BY TIM CROUCH unicorntheatre.com timcrouchtheatre.co.uk I, MALVOLIO TEACHER RESOURCES INTRODUCTION Introduction by Tim Crouch I played the part of Malvolio in a production of Twelfth Night many years ago. Even though the audience laughed, for me, it didn’t feel like a comedy. He is a desperately unhappy man – a fortune spent on therapy would only scratch the surface of his troubles. He can’t smile, he can’t express his feelings; he is angry and repressed and deluded and intolerant, driven by hate and a warped sense of self-importance. His psychiatric problems seem curiously modern. Freud would have had a field day with him. So this troubled man is placed in a comedy of love and mistaken identity. Of course, his role in Twelfth Night would have meant something very different to an Elizabethan audience, but this is now – and his meaning has become complicated by our modern understanding of mental illness and madness. On stage in Twelfth Night, I found the audience’s laughter difficult to take. Malvolio suffers the thing we most dread – to be ridiculed when he is at his most vulnerable. He has no resolution, no happy ending, no sense of justice. His last words are about revenge and then he is gone. This, then, felt like the perfect place to start with his story. My play begins where Shakespeare’s play ends. We see Malvolio how he is at the end of Twelfth Night and, in the course of I, Malvolio, he repairs himself to the state we might have seen him in at the beginning. -

We Still Remember Them

JULYx2014 Final 8_WN.QXD 23/06/2014 11:12 Page 1 Westcombe NEWS Free to 3800 homes, and in libraries & some shops July/August 2014 Issue 6 A community newspaper commended by the London Forum of Amenity and Civic Societies Monthly newspaper of The Westcombe Society: fostering a sense of community We Still Remember Them Neville Grant orld War 1 started on August 4th * The Sewell family. When war broke W1914, when almost exactly a out, Harry Sewell a solicitor who lived at hundred years ago Great Britain declared 26 Crooms Hill, Greenwich, enlisted (then war on Germany. This tragic anniversary is aged 51) in the RAMC. Harry survived the being commemorated not just in this war, and his funeral was at St Alphege's in country, but all over the world Greenwich; he is buried in Charlton. Commemorated, but not celebrated, for All five of his sons also enlisted: two of historians all agree that the war was a them – Frank and Leonard – survived; tragedy for European civilization (even if Harry, Henry and Cecil – all John Roan they disagree on causes, and who if anyone boys – died. 2nd. Lt Henry Sewell’s body was to blame – and even how necessary, or was never found, and he is commemorated avoidable, the war was.) at Thiepval Memorial; Lt. Harry Sewell The War Memorial at the top of Maze Hill commemorating the over 1600 Greenwich In this spirit of commemoration, and was invalided home from Mesopotamia residents killed in World War 1, and the casualties of World War 2. The One sad reflection, the WN remembers all and died in August 1917. -

Download (828Kb)

Original citation: Purcell, Stephen (2018) Are Shakespeare's plays always metatheatrical? Shakespeare Bulletin, 36 (1). pp. 19-35.doi:10.1353/shb.2018.0002 Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/97244 Copyright and reuse: The Warwick Research Archive Portal (WRAP) makes this work by researchers of the University of Warwick available open access under the following conditions. Copyright © and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable the material made available in WRAP has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full items can be used for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge. Provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. Publisher’s statement: © 2018 The John Hopkins University Press. The article first appeared in Shakespeare Bulletin, 36 (1). pp. 19-35. March, 2018. A note on versions: The version presented here may differ from the published version or, version of record, if you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the ‘permanent WRAP URL’ above for details on accessing the published version and note that access may require a subscription. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Are Shakespeare’s plays always metatheatrical? STEPHEN PURCELL University of Warwick The ambiguity of the term “metatheatre” derives in part from its text of origin, Lionel Abel’s 1963 book of the same name. -

Encountering Shakespeare with Tim Crouch

“This is you”: Encountering Shakespeare with Tim Crouch by Sara Soncini By general consensus, Tim Crouch is one of the most innovative theatre-makers to have emerged on the UK scene during the last decade or so. His work has attracted considerable critical attention both nationally and internationally, giving rise to a sizeable and ever expanding body of academic analysis. Starting with his multi-award- winning production of An Oak Tree (2005), Crouch’s plays have toured extensively and they are regularly performed in translation in a wide range of European countries, where they have been invariably hailed as a token of the vigour and vibrancy of British new writing. The fact that roughly one half of Tim Crouch’s dramatic output to date is a reworking of Shakespearean sources is a telling indication of the continued centrality of his theatrical voice on the 21st-century stage. Yet while critics usually remark upon the continuities – in terms of objectives, methods and techniques – between Crouch’s Shakespeare project and the rest of his production (see e.g. Rebellato 2016), the specific cultural meaning of his adaptations as a form of creative engagement with Shakespeare has only been cursorily addressed in the available scholarship. This is arguably a consequence of the particular slant of the project and its perceived specialized nature. Now a cycle of five solo plays, Tim Crouch’s I, Shakespeare was initially instigated by a commission from the Brighton Festival to introduce Shakespeare to a young audience. The brief resulted in I, Caliban (2003), a retelling of Saggi/Ensayos/Essais/Essays Will forever young! Shakespeare & Contemporary Culture – 11/2017 22 The Tempest from the point of view of Shakespeare’s outcast for children aged 8+. -

Book of Abstracts

ABSTRACTS AND BIOGRAPHIES Thursday, October 11, 2018 9.45 PANEL: Across Languages Chair: Claire Hélie (Lille University) 1. Maggie Rose (Milan University) Importing new British plays to Italy. Rethinking the role of the theatre translator Over the last three decades I have worked as a co-translator and a cultural mediator between the UK and Italy, bringing plays by Alan Bennett, Edward Bond, Caryl Churchill, Claire Dowie, David Greig, Kwame Kwei-Armah, Hanif Kureishi, Liz Lochhead, Sabrina Mahfouz, Rani Moorthy, among others,to the Italian stage. Bearing in mind a complex web of Italo-British relations, I will discuss how my strategies of cultural mediation have evolved over the years as a response to significant changes in the two theatre systems. I will explore why the task of finding a publisher and a producer\director for some British authors has been more difficult than for others, the stage and critical success of certain dramatists in Italy more limited. I will look specifically at the Italian ‘journeys’ of the following writers: Caryl Churchill and my co-translation of Top Girls (1986) and A Mouthful of Birds, Edward Bond and my co-translation of The War Plays for the 2006 Winter Olympics in Turin and Alan Bennett and my co-translation of The History Boys at Teatro Elfo Pucini from 2011-3013, at Teatro Elfo Puccini and national tours. Maggie Rose teaches British Theatre Studies and Performance at the University of Milan and spends part of the year in the UK for her writing and research. She is a member of the Scottish Society of Playwrights and her plays have been performed in the UK and in Italy. -

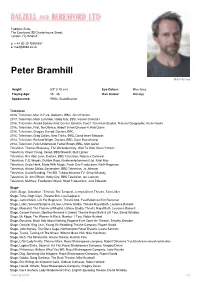

Peter Bramhill Matt Hussey

Paddock Suite, The Courtyard, 55 Charterhouse Street, London, EC1M 6HA p: + 44 (0) 20 73360351 e: [email protected] Peter Bramhill Matt Hussey Height: 5'9" (175 cm) Eye Colour: Blue-Grey Playing Age: 35 - 45 Hair Colour: Blond(e) Appearance: White, Scandinavian Television 2019, Television, Man In Park, Alabama, BBC, Jim O'Hanlon 2017, Television, Mark Lumsden, Holby City, BBC, Various Directors 2016, Television, Arnold Sommerfeld, Genius: Einstein, Fox21 Television Studios, National Geographic, Kevin Hooks 2016, Television, Pilot, No Offence, Abbott Vision Channel 4, Rob Quinn 2016, Television, Gregory Garrod, Doctors, BBC, 2015, Television, Greg Collins, New Tricks, BBC, David Innes-Edwards 2013, Television, Richard Wright, Doctors, BBC, Dave Beauchamp 2013, Television, Felix Underwood, Father Brown, BBC, Matt Carter Television, Thomas Blakeway, The Wickedest City, Wall To Wall, Diene Petterle Television, Oliver Young, Vexed, BBC/Greenlit, Matt Lipsey Television, Rev Able Lunn, Doctors, BBC Television, Rebecca Gatward Television, P.C. Woods, Dustbin Baby, Kindle entertainment Ltd, Juliet May Television, Uncle Hank, Made With Magic, Fresh One Productions, Keith Rogerson Television, Alistair Childs, Eastenders, BBC Television, Jo Johnson Television, David Standing, The Bill, Talkbackthames TV, Simon Massey Television, Dr Jim O'Brien, Holby City, BBC Television, Ian Jackson Television, Matthew, Footballers Wives, Shed Productions, Julie Edwards Stage 2020, Stage, Sebastian / Trinculo, The Tempest, Jermyn Street Theatre, Tom Littler Stage, -

David Greig's Theatre

THE “POLETHICS” OF THE MEDIATED/TIZED SPECTATOR IN THE GLOBAL-TECHNOLOGIZED AGE: DAVID GREIG’S THEATRE Verónica Rodríguez Universidad de Barcelona Abstract: Contemporary Scottish playwright David Greig’s dramaturgy has been concerned with the massive changes wrought across the world by neoliberal globalization in the last two decades. A political triple turn comprising ethics, the media and the spectator, and a shift between the notion “‘mediatized’ reiterative ‘expectator’” to “mediated performing spectator” within the “polethic” frame of ‘relationality’ in Greig’s works are argued in this article. It is further argued that the plays examined (Damascus, The American Pilot, Brewers Fayre and Fragile) use productive strategies like diffusion, reversibility and interchangeability, which foreground the asymmetries of the global/technologized age “polethically” mediating the global performing spectator. Key Words: Globalization, David Greig, Media, Spectator, Ethics, Politics. Recibido: 18/07/2012 Aceptado: 05/09/2012 TRIPLE TURN: ETHICS, MEDIA & SPECTATORSHIP IN THE GLOBAL-TECHNOLOGIZED AGE In his short review of Michael Kustov’s Theatre@risk, David Greig states that “[t]he thrust of Kustow’s argument is that in a corporate, mediated, screened world the last public space – public in the true sense – is the theatre” (Glasgow Sunday Herald)1 adding that he shares “his passion and confidence that theatre is the necessary art form of the century” (ibid.). Greig’s theatre emerges as a creative response in this milieu by raising questions around the role of ethics, the media and spectators in the context of the global-technologized age when the idea of the nation is being 1 This review appears at the beginning of the 2000’s Methuen edition of Kustov’s Theare@risk. -

Juliana Pedreira De Freitas

Juliana Pedreira de Freitas A CENOGRAFIA NO PALCO DE SHAKESPEARE Dissertação apresentada ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Artes, Área de Concentração Artes Cênicas, Linha de Pesquisa Prática Teatral, da Escola de Comunicações e Artes da Universidade de São Paulo, como exigência parcial para a obtenção do Título de Mestre em Artes, sob a orientação do Prof. Dr. Cyro Del Nero de Oliveira Pinto. São Paulo 2009 2 A CENOGRAFIA NO PALCO DE SHAKESPEARE Aprovada em:__________________________________________________________ Banca examinadora: Prof. Dr. __________________________________________________________ Assinatura: __________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. __________________________________________________________ Assinatura: __________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. __________________________________________________________ Assinatura: __________________________________________________________ 3 RESUMO O teatro não pode ser traduzido apenas como um texto literário, ele é a junção da obra dramatúrgica com tudo aquilo que pode ser colocado sobre o palco. Partindo desse ponto de vista, ao entendermos como eram os cenários de Shakespeare na sua origem, melhor interpretaríamos o real significado de sua obra, facilitando assim a sua compreensão e gerando mais uma ferramenta de trabalho para que possamos recriar seus textos. Acreditando nisso, baseamos este estudo nos elementos práticos inseridos na realização teatral do século XVI e XVII na Inglaterra. Passamos por uma breve concepção histórica -

Laughing out Young: Laughter in Evan Placey's Girls Like That And

Miranda Revue pluridisciplinaire du monde anglophone / Multidisciplinary peer-reviewed journal on the English- speaking world 19 | 2019 Rethinking Laughter in Contemporary Anglophone Theatre Laughing Out Young: Laughter in Evan Placey’s Girls Like That and Other Plays for Teenagers (2016) Claire Hélie Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/20064 DOI: 10.4000/miranda.20064 ISSN: 2108-6559 Publisher Université Toulouse - Jean Jaurès Printed version Date of publication: 7 October 2019 Electronic reference Claire Hélie, “Laughing Out Young: Laughter in Evan Placey’s Girls Like That and Other Plays for Teenagers (2016)”, Miranda [Online], 19 | 2019, Online since 09 October 2019, connection on 16 February 2021. URL: http://journals.openedition.org/miranda/20064 ; DOI: https://doi.org/10.4000/ miranda.20064 This text was automatically generated on 16 February 2021. Miranda is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Laughing Out Young: Laughter in Evan Placey’s Girls Like That and Other Plays... 1 Laughing Out Young: Laughter in Evan Placey’s Girls Like That and Other Plays for Teenagers (2016) Claire Hélie 1 Evan Placey1 is a Canadian-British playwright who writes for young audiences; but unlike playwrights such as Edward Bond, Dennis Kelly or Tim Crouch, he writes for young audiences only. Some of his plays target young children, like WiLd! (2016), the monologue of an 8-year-old boy with ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), other young adults, like Consensual (2015), which explores the grey area between rape and consent. His favourite audience remain teenagers and four of the plays he wrote for them were collected in Girls Like That and Other Plays for Teenagers in 2016. -

Transparency List Extract from BBGM - Projects with Start Date from 1 April 2015

Transparency List Extract from BBGM - projects with start date from 1 April 2015 Grant Award Organisation Organisation Strand (if Date Project Start Date Project End Date LBTH Directorate Organisation Name Organisation Address Charity Number Company Number Fund Fund/Program applicable) Project Title Short Description Grant Amount Norvin House Volunteer Centre Tower 45-55 Commercial Street To assist in dealing with an unforeseeable emergency and/or to support 25/03/2015 01/04/2015 30/09/2015 Resources Hamlets London E1 6BD 1127300 6638750 Emergency Funding Emergency Funding VCTH Emergency Funding organisational development and sustainability 19,936.00 6 The Hawthornes, Whitehall Road, Woodford Green, To assist in dealing with an unforeseeable emergency and/or to support 31/03/2015 01/04/2015 30/09/2015 Resources Senrab Football Club Essex IG8 0RN Emergency Funding Emergency Funding Senrab FC - Emergency Funding organisational development and sustainability 5,330.00 Tower Hamlets Somali Organisations Network 18a Victoria Park Square THSON: Bringing Us Together for Football and Mutual 09/09/2015 20/06/2015 29/08/2015 LPG (THSON) London E2 9PF 1153710 05648113 One Tower Hamlets One Tower Hamlets Respect 5,230.00 St Hilda's East Community 18 Cub Row Established Wisdom: Celebrating Diversity in Tower 27/05/2015 04/05/2015 03/12/2015 LPG Centre London E2 7EY 212208 52880 One Tower Hamlets One Tower Hamlets Hamlets. 5,958.00 SocietyLinks Tower 80 John Fisher St 09/09/2015 05/06/2015 08/01/2016 LPG Hamlets London E1 8JX 1154824 7750061 One Tower -

Impact Case Study

Impact case study (REF3b) Institution: University of Warwick Unit of Assessment: 29 English Language and Literature Title of case study: Shakespeare in Performance: informing theatrical productions and promoting British cultural engagement 1. Summary of the impact Performance brings Shakespeare alive and each performance reveals new contexts for, and meanings to his plays. Research on Shakespeare in Performance is a core departmental activity that encompasses complementary themes and leads to impacts across a wide range of strands and fields. Warwick’s Shakespeare scholars have explored the relationship between text and performance to bring a new understanding of Shakespeare to professional theatre companies and a renewed enjoyment to public audiences. In particular, their research has impacted on theatre productions, exhibitions, and public understanding through screenings, workshops, talks, young people’s theatre and schools. 2. Underpinning research Warwick’s English Department is a leading centre for research into Shakespeare in Performance, exploring the ways in which Shakespeare is adapted and interpreted for the stage and how such representations refract and reflect social and cultural values. The research underpinning the impacts has been conducted by Professor Jonathan Bate (2003-2011), Professor Tony Howard (1973-present), Dr Paul Prescott (2005-present), Dr Stephen Purcell (2011-present), and Professor Carol Chillington Rutter (1989-present). The key themes of this research group are: 1. Minorities on stage: exploring the presence of historically under-represented and unacknowledged groups on stage In his monograph Women as Hamlet: Performance as Interpretation in Theatre, Film and Fiction (2007) Howard explores the construction of the female Hamlet in novels, plays and films.