1 Yorkshire Palliative Medicine Clinical Guidelines Group

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stopping Antidepressants

Stopping antidepressants This information is for anyone who wants to know more about stopping antidepressants. It describes: symptoms that you may get when stopping an antidepressant some ways to reduce or avoid these symptoms. This patient information accurately reflects recommendations in the NICE guidance on depression in adults Disclaimer This resource provides information, not advice. The content in this resource is provided for general information only. It is not intended to, and does not, amount to advice which you should rely on. It is not in any way an alternative to specific advice. You must therefore obtain the relevant professional or specialist advice before taking, or refraining from, any action based on the information in this resource. If you have questions about any medical matter, you should consult your doctor or other professional healthcare provider without delay. If you think you are experiencing any medical condition, you should seek immediate medical attention from a doctor or other professional healthcare provider. Although we make reasonable efforts to compile accurate information in our resources and to update the information in our resources, we make no representations, warranties or guarantees, whether express or implied, that the content in this resource is accurate, complete or up to date. What are antidepressants? They are medications prescribed for depressive illness, anxiety disorder or obsessive- compulsive disorder (OCD). You can find out more about how they work, why they are prescribed, their effects and side-effects, and alternative treatments in our separate resource on antidepressants. Usually, you don’t need to take antidepressants for more than 6 to 12 months. -

Impact of CYP2C19 Genotype on Sertraline Exposure in 1200 Scandinavian Patients

www.nature.com/npp ARTICLE Impact of CYP2C19 genotype on sertraline exposure in 1200 Scandinavian patients Line S. Bråten 1,2, Tore Haslemo1,2, Marin M. Jukic3,4, Magnus Ingelman-Sundberg 3, Espen Molden1,5 and Marianne K. Kringen1,2 Sertraline is an (SSRI-)antidepressant metabolized by the polymorphic CYP2C19 enzyme. The aim of this study was to investigate the impact of CYP2C19 genotype on the serum concentrations of sertraline in a large patient population. Second, the proportions of patients in the various CYP2C19 genotype-defined subgroups obtaining serum concentrations outside the therapeutic range of sertraline were assessed. A total of 2190 sertraline serum concentration measurements from 1202 patients were included retrospectively from the drug monitoring database at Diakonhjemmet Hospital in Oslo. The patients were divided into CYP2C19 genotype-predicted phenotype subgroups, i.e. normal (NMs), ultra rapid (UMs), intermediate (IMs), and poor metabolisers (PMs). The differences in dose-harmonized serum concentrations of sertraline and N-desmethylsertraline-to-sertraline metabolic ratio were compared between the subgroups, with CYP2C19 NMs set as reference. The patient proportions outside the therapeutic concentration range were also compared between the subgroups with NMs defined as reference. Compared with the CYP2C19 NMs, the sertraline serum concentration was increased 1.38-fold (95% CI 1.26–1.50) and 2.68-fold (95% CI 2.16–3.31) in CYP2C19 IMs and PMs, respectively (p < 0.001), while only a marginally lower serum concentration (−10%) was observed in CYP2C19 UMs (p = 0.012). The odds ratio for having a sertraline concentration above the therapeutic reference range was 1.97 (95% CI 1.21–3.21, p = 0.064) and 8.69 (95% CI 3.88–19.19, p < 0.001) higher for IMs and PMs vs. -

ZOLOFT® 50 Mg and 100 Mg Tablets

NEW ZEALAND DATA SHEET 1. PRODUCT NAME ZOLOFT® 50 mg and 100 mg tablets 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each 50 mg tablet contains sertraline hydrochloride equivalent to 50 mg sertraline. Each 100 mg tablet contains sertraline hydrochloride equivalent to 100 mg sertraline. For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM ZOLOFT 50 mg tablets: white film-coated tablets marked with the Pfizer logo on one side and “ZLT” scoreline “50” on the other. Approximate tooling dimensions are 1.03 cm x 0.42 cm x 0.36 cm. ZOLOFT 100 mg tablets: white film-coated tablets marked with the Pfizer logo on one side and “ZLT-100” or “ZLT 100” on the other. Approximate tooling dimensions are 1.31 cm x 0.52 cm x 0.44 cm. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Adults ZOLOFT is indicated for the treatment of symptoms of depression, including depression accompanied by symptoms of anxiety, in patients with or without a history of mania. Following satisfactory response, continuation with ZOLOFT therapy is effective in preventing relapse of the initial episode of depression or recurrence of further depressive episodes. ZOLOFT is indicated for the treatment of obsessive compulsive disorder (OCD). Following initial response, sertraline has been associated with sustained efficacy, safety and tolerability in up 2 years of treatment of OCD. ZOLOFT is indicated for the treatment of panic disorder, with or without agoraphobia. ZOLOFT is indicated for the treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). ZOLOFT is indicated for the treatment of social phobia (social anxiety disorder). -

Differential Effects on Suicidal Ideation of Mianserin, Maprotiline and Amitriptyline S

Br. J. clin. Pharmac. (1978), 5, 77S-80S DIFFERENTIAL EFFECTS ON SUICIDAL IDEATION OF MIANSERIN, MAPROTILINE AND AMITRIPTYLINE S. MONTGOMERY Academic Department of Psychiatry, Guy's Hospital Medical School, London Bridge, London SE1 9RT, UK B. CRONHOLM, MARIE ASBERG Karolinska Institute, Stockholm D.B. MONTGOMERY Institute of Psychiatry, De Crespigny Park, Denmark Hill, London SE5 8AF, U K 1 Eighty patients suffering from primary depressive illness were treated for 4 weeks, following a 7-d (at least) no-treatment period, with either mianserin 60 mg daily (n = 50), maprotiline 150 mg at night- time (n = 15) or amitriptyline 150 mg at night-time (n = 15) in double-blind controlled trials run con- currently in the same hospital on protocols having the same design and entry criteria. 2 The effects of the three drugs were examined for their proffle of action using a new depression rating scale (Montgomery and Asberg Depression Scale, MADS) claimed to be more sensitive to change. There was no significant difference in mean entry scores or mean amelioration of depression on the MADS or the Hamilton Rating Scale (HRS) between the three drugs, but individual items on the MADS did show significant differences in amelioration. A highly significant (P < 0.01) difference was observed in favour of mianserin against maprotiline on both items of'suicidal thoughts' and 'pessimistic thoughts' on the MADS. The suicidal item on the HRS showed a similar tendency which did not reach significance. 3 This finding is considered in relation to a possible mode of action of mianserin and the relevance to reported subgroups ofdepressive illness with increased suicidal ideation. -

Dose Equivalents of Antidepressants Evidence-Based Recommendations

Journal of Affective Disorders 180 (2015) 179–184 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Affective Disorders journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jad Research report Dose equivalents of antidepressants: Evidence-based recommendations from randomized controlled trials Yu Hayasaka a,n, Marianna Purgato b, Laura R Magni c, Yusuke Ogawa a, Nozomi Takeshima a, Andrea Cipriani b,d, Corrado Barbui b, Stefan Leucht e, Toshi A Furukawa a a Department of Health Promotion and Human Behavior, Kyoto University Graduate School of Medicine/School of Public Health, Yoshida Konoe-cho, Sakyo- ku, Kyoto 606-8501, Japan b Department of Public Health and Community Medicine, Section of Psychiatry, University of Verona, Policlinico “G.B.Rossi”, Pzz.le L.A. Scuro, 10, Verona 37134, Italy c Psychiatric Unit, Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico, Centro San Giovanni di Dio, Fatebenefratelli, Brescia, Italy d Department of Psychiatry, University of Oxford, Oxford, UK e Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Technische Universität München, Klinikum rechts der Isar, Ismaningerstr. 22, 81675 Munich, Germany article info abstract Article history: Background: Dose equivalence of antidepressants is critically important for clinical practice and for Received 4 February 2015 research. There are several methods to define and calculate dose equivalence but for antidepressants, Received in revised form only daily defined dose and consensus methods have been applied to date. The purpose of the present 10 March 2015 study is to examine dose equivalence of antidepressants by a less arbitrary and more systematic method. Accepted 12 March 2015 Methods: We used data from all randomized, double-blind, flexible-dose trials comparing fluoxetine or Available online 31 March 2015 paroxetine as standard drugs with any other active antidepressants as monotherapy in the acute phase Keywords: treatment of unipolar depression. -

Product Monograph

PRODUCT MONOGRAPH PrFLUANXOL® Flupentixol Tablets (as flupentixol dihydrochloride) 0.5 mg, 3 mg, and 5 mg PrFLUANXOL® DEPOT Flupentixol Decanoate Intramuscular Injection 2% and 10% flupentixol decanoate Antipsychotic Agent Lundbeck Canada Inc. Date of Revision: 2600 Alfred-Nobel December 12th, 2017 Suite 400 St-Laurent, QC H4S 0A9 Submission Control No : 209135 Page 1 of 35 Table of Contents PART I: HEALTH PROFESSIONAL INFORMATION .........................................................3 SUMMARY PRODUCT INFORMATION ........................................................................3 INDICATIONS AND CLINICAL USE ..............................................................................3 CONTRAINDICATIONS ...................................................................................................4 WARNINGS AND PRECAUTIONS ..................................................................................4 ADVERSE REACTIONS ..................................................................................................10 DRUG INTERACTIONS ..................................................................................................13 DOSAGE AND ADMINISTRATION ..............................................................................15 OVERDOSAGE ................................................................................................................18 ACTION AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY ............................................................19 STORAGE AND STABILITY ..........................................................................................21 -

Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Joint Prescribing Group MEDICINE REVIEW

Cambridgeshire and Peterborough Joint Prescribing Group MEDICINE REVIEW Name of Medicine / Trimipramine (Surmontil®) Class (generic and brand) Licensed indication(s) Treatment of depressive illness, especially where sleep disturbance, anxiety or agitation are presenting symptoms. Sleep disturbance is controlled within 24 hours and true antidepressant action follows within 7 to 10 days. Licensed dose(s) Adults: For depression 50-75 mg/day initially increasing to 150-300 mg/day in divided doses or one dose at night. The maintenance dose is 75-150 mg/day. Elderly: 10-25 mg three times a day initially. The initial dose should be increased with caution under close supervision. Half the normal maintenance dose may be sufficient to produce a satisfactory clinical response. Children: Not recommended. Purpose of Document To review information currently available on this class of medicines, give guidance on potential use and assign a prescribing classification http://www.cambsphn.nhs.uk/CJPG/CurrentDrugClassificationTable.aspx Annual cost (FP10) 10mg three times daily: £6,991 25mg three times daily: £7,819 150mg daily: £7,410 300mg daily: £14,820 Alternative Treatment Options within Class Tricyclic Annual Cost CPCCG Formulary Classification Antidepressant (FP10) Amitriptyline (75mg) Formulary £36 Lofepramine (140mg) Formulary £146 Imipramine (75mg) Non-formulary £37 Clomipramine (75mg) Non-formulary £63 Trimipramine (75mg). TBC £7,819 Nortriptyline (75mg) Not Recommended (pain) £276 Doxepin (150mg) TBC £6,006 Dosulepin (75mg) Not Recommended (NICE DO NOT DO) £19 Dosages are based on possible maintenance dose and are not equivalent between medications Recommendation It is recommended to Cambridgeshire and Peterborough CCG JPG members and through them to local NHS organisations that the arrangements for use of trimipramine are in line with restrictions agreed locally for drugs designated as NOT RECOMMENDED:. -

Properties and Units in Clinical Pharmacology and Toxicology

Pure Appl. Chem., Vol. 72, No. 3, pp. 479–552, 2000. © 2000 IUPAC INTERNATIONAL FEDERATION OF CLINICAL CHEMISTRY AND LABORATORY MEDICINE SCIENTIFIC DIVISION COMMITTEE ON NOMENCLATURE, PROPERTIES, AND UNITS (C-NPU)# and INTERNATIONAL UNION OF PURE AND APPLIED CHEMISTRY CHEMISTRY AND HUMAN HEALTH DIVISION CLINICAL CHEMISTRY SECTION COMMISSION ON NOMENCLATURE, PROPERTIES, AND UNITS (C-NPU)§ PROPERTIES AND UNITS IN THE CLINICAL LABORATORY SCIENCES PART XII. PROPERTIES AND UNITS IN CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY AND TOXICOLOGY (Technical Report) (IFCC–IUPAC 1999) Prepared for publication by HENRIK OLESEN1, DAVID COWAN2, RAFAEL DE LA TORRE3 , IVAN BRUUNSHUUS1, MORTEN ROHDE1, and DESMOND KENNY4 1Office of Laboratory Informatics, Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), Copenhagen, Denmark; 2Drug Control Centre, London University, King’s College, London, UK; 3IMIM, Dr. Aiguader 80, Barcelona, Spain; 4Dept. of Clinical Biochemistry, Our Lady’s Hospital for Sick Children, Crumlin, Dublin 12, Ireland #§The combined Memberships of the Committee and the Commission (C-NPU) during the preparation of this report (1994–1996) were as follows: Chairman: H. Olesen (Denmark, 1989–1995); D. Kenny (Ireland, 1996); Members: X. Fuentes-Arderiu (Spain, 1991–1997); J. G. Hill (Canada, 1987–1997); D. Kenny (Ireland, 1994–1997); H. Olesen (Denmark, 1985–1995); P. L. Storring (UK, 1989–1995); P. Soares de Araujo (Brazil, 1994–1997); R. Dybkær (Denmark, 1996–1997); C. McDonald (USA, 1996–1997). Please forward comments to: H. Olesen, Office of Laboratory Informatics 76-6-1, Copenhagen University Hospital (Rigshospitalet), 9 Blegdamsvej, DK-2100 Copenhagen, Denmark. E-mail: [email protected] Republication or reproduction of this report or its storage and/or dissemination by electronic means is permitted without the need for formal IUPAC permission on condition that an acknowledgment, with full reference to the source, along with use of the copyright symbol ©, the name IUPAC, and the year of publication, are prominently visible. -

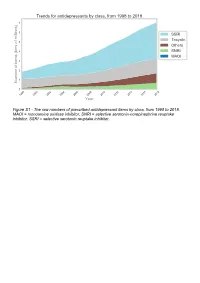

The Raw Numbers of Prescribed Antidepressant Items by Class, from 1998 to 2018

Figure S1 - The raw numbers of prescribed antidepressant items by class, from 1998 to 2018. MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor, SNRI = selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Figure S2 - The raw numbers of prescribed antidepressant items for the ten most commonly prescribed antidepressants (in 2018), from 1998 to 2018. Figure S3 - Practice level percentile charts for the proportions of the ten most commonly prescribed antidepressants (in 2018), prescribed between August 2010 and November 2019. Deciles are in blue, with median shown as a heavy blue line, and extreme percentiles are in red. Figure S4 - Practice level percentile charts for the proportions of specific MAOIs prescribed between August 2010 and November 2019. Deciles are in blue, with median shown as a heavy blue line, and extreme percentiles are in red. Figure S5 - CCG level heat map for the percentage proportions of MAOIs prescribed between December 2018 and November 2019. MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor. Figure S6 - CCG level heat maps for the percentage proportions of paroxetine, dosulepin, and trimipramine prescribed between December 2018 and November 2019. Table S1 - Antidepressant drugs, by category. MAOI = monoamine oxidase inhibitor, SNRI = selective serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor, SSRI = selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor. Class Drug MAOI Isocarboxazid, moclobemide, phenelzine, tranylcypromine SNRI Duloxetine, venlafaxine SSRI Citalopram, escitalopram, fluoxetine, fluvoxamine, paroxetine, -

Depot Antipsychotic Injections

Mental Health Services Good Practice Statement For The Use Of DEPOT & LONG ACTING ANTIPSYCHOTIC INJECTIONS Date of Revision: February 2020 Approved by: Mental Health Prescribing Management Group Review Date: CONSULTATION The document was sent to Community Mental Health teams, Pharmacy and the Psychiatric Advisory Committee for comments prior to completion. KEY DOCUMENTS When reading this policy please consult the NHS Consent Policy when considering any aspect of consent National Institute for Clinical Excellence CG178 (2014), Psychosis and schizophrenia in adults: prevention and management NHS Lothian (2011), Depot Antipsychotic Guidance, Maudsley (2015), Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry 12th edition. UKPPG (2009) Guidance on the Administration to Adults of Oil based Depot and other Long Acting Intramuscular Antipsychotic Injections Summary of Product Characteristics for: Clopixol (Zuclopethixol Decanoate) Flupenthixol Decanoate Haldol (Haloperidol Decanoate) Risperdal Consta Xeplion (Paliperidone Palmitate) ZypAdhera (Olanzapine Embonate) Abilify Maintena (Aripiprazole) 1 CONTENTS REFERENCES/KEY DOCUMENTS …………………………………………………………… 1 INTRODUCTION …………………………………………………………………………………. 3 SCOPE …………………………………………………………………………………………….. 3 DEFINITIONS ……………………………………………………………………………………... 3 CHOICE OF DRUG AND DOSAGE SELECTION ……………………………………………. 3 SIDE EFFECTS ……………………………………………………………….………………….. 5 PRESCRIBING …………………………………………………………………………………… 5 ADMINISTRATION ………………………………………………………………………………. 7 RECORDING ADMINISTRATION ……………………………………………………………… 7 -

Deanxit SPC.Pdf

SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS 1. NAME OF THE MEDICINAL PRODUCT Deanxit film-coated tablets 2. QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Each tablet contains: Flupentixol 0.5 mg (as 0.584 mg flupentixol dihydrochloride) Melitracen 10 mg (as 11.25 mg melitracen hydrochloride) Excipients with known effect: Lactose monohydrate For the full list of excipients, see section 6.1. 3. PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Film-coated tablets. Round, biconvex, cyclamen, film-coated tablets. 4. CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 Therapeutic indications Anxiety Depression Asthenia. Neurasthenia. Psychogenic depression. Depressive neuroses. Masked depression. Psychosomatic affections accompanied by anxiety and apathy. Menopausal depressions. Dysphoria and depression in alcoholics and drug-addicts. 4.2 Posology and method of administration Posology Adults Usually 2 tablets daily: morning and noon. In severe cases the morning dose may be increased to 2 tablets. The maximum dose is 4 tablets daily. Older people (> 65 years) 1 tablet in the morning. In severe cases 1 tablet in the morning and 1 at noon. Maintenance dose: Usually 1 tablet in the morning. SPC Portrait-REG_00051968 20v038 Page 1 of 10 In cases of insomnia or severe restlessness additional treatment with a sedative in the acute phase is recommended. Paediatric population Children and adolescents (<18 years) Deanxit is not recommended for use in children and adolescents due to lack of data on safety and efficacy. Reduced renal function Deanxit can be given in the recommended doses. Reduced liver function Deanxit can be given in the recommended doses. Method of administration The tablets are swallowed with water. 4.3 Contraindications Hypersensitivity to flupentixol and melitracen or to any of the excipients listed in section 6.1. -

LUMIN Mianserin Hydrochloride Tablets

AUSTRALIAN PRODUCT INFORMATION LUMIN Mianserin hydrochloride tablets 1 NAME OF THE MEDICINE Mianserin hydrochloride 2 QUALITATIVE AND QUANTITATIVE COMPOSITION Mianserin belongs to the tetracyclic series of antidepressant compounds, the piperazinoazepines. These are chemically different from the common tricyclic antidepressants. Each Lumin 10 tablet contains 10 mg of mianserin hydrochloride and each Lumin 20 tablet contains 20 mg of mianserin hydrochloride as the active ingredient. Lumin also contains trace amounts of sulfites. For the full list of excipients, see Section 6.1 List of Excipients. 3 PHARMACEUTICAL FORM Lumin 10: 10 mg tablet: white, film coated, normal convex, marked MI 10 on one side, G on reverse Lumin 20: 20 mg tablet: white, film coated, normal convex, marked MI 20 on one side, G on reverse 4 CLINICAL PARTICULARS 4.1 THERAPEUTIC INDICATIONS For the treatment of major depression. 4.2 DOSE AND METHOD OF ADMINISTRATION Lumin tablets should be taken orally between meals, preferably with a little fluid, and swallowed without chewing. Use in Children and Adolescents (< 18 years of age) Lumin should not be used in children and adolescents under the age of 18 years (see section 4.4 Special Warnings and Precautions for use). Adults The initial dosage of Lumin should be judged individually. It is recommended that treatment begin with a daily dose of 30 mg given in three divided doses or as a single bedtime dose and be adjusted weekly in the light of the clinical response. The effective daily dose for adult patients usually lies between 30 mg and 90 mg (average 60 mg) in divided doses or as a single bedtime dose.