The Consolidation of Political Power in China Under Xi Jinping

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comparative Connections a Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations

Comparative Connections A Triannual E-Journal on East Asian Bilateral Relations China-Russia Relations: Navigating through the Ukraine Storm Yu Bin Wittenberg University Against the backdrop of escalating violence in Ukraine, Sino-Russian relations were on the fast track over the past four months in three broad areas: strategic coordination, economics, and mil- mil relations. This was particularly evident during President Putin’s state visit to China in late May when the two countries inked a 30-year, $400 billion gas deal after 20 years of hard negotiation. Meanwhile, the two navies were drilling off the East China Sea coast and the Conference on Interaction and Confidence Building Measures in Asia (CICA) was being held in Shanghai. Beyond this, Moscow and Beijing were instrumental in pushing the creation of the $50 billion BRICS development bank and a $100 billion reserve fund after years of frustrated waiting for a bigger voice for the developing world in the IMF and World Bank. Putin in Shanghai for state visit and more President Vladimir Putin traveled to Shanghai on May 20-21 to meet Chinese counterpart Xi Jinping. This was the seventh time they have met since March 2013 when Xi assumed the presidency in China. The trip was made against a backdrop of a deepening crisis in Ukraine: 42 pro-Russian activists were killed in the Odessa fire on May 2 and pro-Russian separatists in Donetsk and Luhansk declared independence on May 11. Four days after Putin’s China trip, the Ukrainian Army unveiled its “anti-terrorist operations,” and on July 17 Malaysia Airlines Flight MH17 was downed. -

Assessing the Training and Operational Proficiency of China's

C O R P O R A T I O N Assessing the Training and Operational Proficiency of China’s Aerospace Forces Selections from the Inaugural Conference of the China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI) Edmund J. Burke, Astrid Stuth Cevallos, Mark R. Cozad, Timothy R. Heath For more information on this publication, visit www.rand.org/t/CF340 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available for this publication. ISBN: 978-0-8330-9549-7 Published by the RAND Corporation, Santa Monica, Calif. © Copyright 2016 RAND Corporation R® is a registered trademark. Limited Print and Electronic Distribution Rights This document and trademark(s) contained herein are protected by law. This representation of RAND intellectual property is provided for noncommercial use only. Unauthorized posting of this publication online is prohibited. Permission is given to duplicate this document for personal use only, as long as it is unaltered and complete. Permission is required from RAND to reproduce, or reuse in another form, any of its research documents for commercial use. For information on reprint and linking permissions, please visit www.rand.org/pubs/permissions. The RAND Corporation is a research organization that develops solutions to public policy challenges to help make communities throughout the world safer and more secure, healthier and more prosperous. RAND is nonprofit, nonpartisan, and committed to the public interest. RAND’s publications do not necessarily reflect the opinions of its research clients and sponsors. Support RAND Make a tax-deductible charitable contribution at www.rand.org/giving/contribute www.rand.org Preface On June 22, 2015, the China Aerospace Studies Institute (CASI), in conjunction with Headquarters, Air Force, held a day-long conference in Arlington, Virginia, titled “Assessing Chinese Aerospace Training and Operational Competence.” The purpose of the conference was to share the results of nine months of research and analysis by RAND researchers and to expose their work to critical review by experts and operators knowledgeable about U.S. -

'New Era' Should Have Ended US Debate on Beijing's Ambitions

Testimony before the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission Hearing on “A ‘China Model?’ Beijing’s Promotion of Alternative Global Norms and Standards” March 13, 2020 “How Xi Jinping’s ‘New Era’ Should Have Ended U.S. Debate on Beijing’s Ambitions” Daniel Tobin Faculty Member, China Studies, National Intelligence University and Senior Associate (Non-resident), Freeman Chair in China Studies, Center for Strategic and International Studies Senator Talent, Senator Goodwin, Honorable Commissioners, thank you for inviting me to testify on China’s promotion of alternative global norms and standards. I am grateful for the opportunity to submit the following statement for the record. Since I teach at National Intelligence University (NIU) which is part of the Department of Defense (DoD), I need to begin by making clear that all statements of fact and opinion below are wholly my own and do not represent the views of NIU, DoD, any of its components, or of the U.S. government. You have asked me to discuss whether China seeks an alternative global order, what that order would look like and aim to achieve, how Beijing sees its future role as differing from the role the United States enjoys today, and also to address the parts played respectively by the Party’s ideology and by its invocation of “Chinese culture” when talking about its ambitions to lead the reform of global governance.1 I want to approach these questions by dissecting the meaning of the “new era for socialism with Chinese characteristics” Xi Jinping proclaimed at the Communist Party of China’s 19th National Congress (afterwards “19th Party Congress”) in October 2017. -

China Data Supplement

China Data Supplement October 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 29 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 36 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 42 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 45 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR................................................................................................................ 54 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR....................................................................................................................... 61 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 66 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 October 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Archaeological Observation on the Exploration of Chu Capitals

Archaeological Observation on the Exploration of Chu Capitals Wang Hongxing Key words: Chu Capitals Danyang Ying Chenying Shouying According to accurate historical documents, the capi- In view of the recent research on the civilization pro- tals of Chu State include Danyang 丹阳 of the early stage, cess of the middle reach of Yangtze River, we may infer Ying 郢 of the middle stage and Chenying 陈郢 and that Danyang ought to be a central settlement among a Shouying 寿郢 of the late stage. Archaeologically group of settlements not far away from Jingshan 荆山 speaking, Chenying and Shouying are traceable while with rice as the main crop. No matter whether there are the locations of Danyang and Yingdu 郢都 are still any remains of fosses around the central settlement, its oblivious and scholars differ on this issue. Since Chu area must be larger than ordinary sites and be of higher capitals are the political, economical and cultural cen- scale and have public amenities such as large buildings ters of Chu State, the research on Chu capitals directly or altars. The site ought to have definite functional sec- affects further study of Chu culture. tions and the cemetery ought to be divided into that of Based on previous research, I intend to summarize the aristocracy and the plebeians. The relevant docu- the exploration of Danyang, Yingdu and Shouying in ments and the unearthed inscriptions on tortoise shells recent years, review the insufficiency of the former re- from Zhouyuan 周原 saying “the viscount of Chu search and current methods and advance some personal (actually the ruler of Chu) came to inform” indicate that opinion on the locations of Chu capitals and later explo- Zhou had frequent contact and exchange with Chu. -

August 10, 2016 the Honorable Li Keqiang Premier Beijing People's

August 10, 2016 The Honorable Li Keqiang Premier Beijing People’s Republic of China Respected Premier Li: Our organizations, representing a broad array of industries and companies of all sizes, are writing to express our hope that China fully embraces the goals of the upcoming G20 Leaders Meeting to promote an “innovative, invigorated, interconnected, and inclusive world economy,” by taking steps to address concerns regarding the direction of China’s information communications technology (ICT) policies. These include the draft Cybersecurity Law (“The Law”) and pending China Insurance Regulatory Commission (CIRC) Provisions on Insurance System Informatization (“The Provisions”). We appreciate that China has published drafts of The Law and The Provisions for public comment. This level of transparency is very important in drafting technical regulations of this significance. However, the current drafts, if implemented, would weaken security and separate China from the global digital economy. Specific concerns with The Law and The Provisions include: Broad data residency requirements, which have no additional security benefits, but would impede economic growth, and create barriers to entry for both foreign and Chinese companies; Trade-inhibiting security reviews and requirements for ICT products and services, which may weaken security and constitute technical barriers to trade as defined by the World Trade Organization; and Data retention and sharing, and law enforcement assistance requirements, which would weaken technical security measures -

Xi Jinping's War on Corruption

University of Mississippi eGrove Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors Theses Honors College) 2015 The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption Harriet E. Fisher University of Mississippi. Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis Part of the Political Science Commons Recommended Citation Fisher, Harriet E., "The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping's War on Corruption" (2015). Honors Theses. 375. https://egrove.olemiss.edu/hon_thesis/375 This Undergraduate Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Honors College (Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College) at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Chinese Inquisition: Xi Jinping’s War on Corruption By Harriet E. Fisher A thesis presented in partial fulfillment of the requirements for completion Of the Bachelor of Arts degree in International Studies at the Croft Institute for International Studies and the Sally McDonnell Barksdale Honors College The University of Mississippi University, Mississippi May 2015 Approved by: ______________________________ Advisor: Dr. Gang Guo ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Kees Gispen ______________________________ Reader: Dr. Peter K. Frost i © 2015 Harriet E. Fisher ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ii For Mom and Pop, who taught me to learn, and Helen, who taught me to teach. iii Acknowledgements I am indebted to a great many people for the completion of this thesis. First, I would like to thank my advisor, Dr. Gang Guo, for all his guidance during the thesis- writing process. His expertise in China and its endemic political corruption were invaluable, and without him, I would not have had a topic, much less been able to complete a thesis. -

Xi Jinping's Address to the Central Conference On

Xi Jinping’s Address to the Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs: Assessing and Advancing Major- Power Diplomacy with Chinese Characteristics Michael D. Swaine* Xi Jinping’s speech before the Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs—held November 28–29, 2014, in Beijing—marks the most comprehensive expression yet of the current Chinese leadership’s more activist and security-oriented approach to PRC diplomacy. Through this speech and others, Xi has taken many long-standing Chinese assessments of the international and regional order, as well as the increased influence on and exposure of China to that order, and redefined and expanded the function of Chinese diplomacy. Xi, along with many authoritative and non-authoritative Chinese observers, presents diplomacy as an instrument for the effective application of Chinese power in support of an ambitious, long-term, and more strategic foreign policy agenda. Ultimately, this suggests that Beijing will increasingly attempt to alter some of the foreign policy processes and power relationships that have defined the political, military, and economic environment in the Asia- Pacific region. How the United States chooses to respond to this challenge will determine the Asian strategic landscape for decades to come. On November 28 and 29, 2014, the Central Chinese Communist Party (CCP) leadership convened its fourth Central Conference on Work Relating to Foreign Affairs (中央外事工作会)—the first since August 2006.1 The meeting, presided over by Premier Li Keqiang, included the entire Politburo Standing Committee, an unprecedented number of central and local Chinese civilian and military officials, nearly every Chinese ambassador and consul-general with ambassadorial rank posted overseas, and commissioners of the Foreign Ministry to the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region and the Macao Special Administrative Region. -

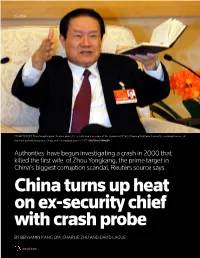

China Turns up Heat on Ex-Security Chief with Crash Probe

CHINA PRIME TARGET: Zhou Yongkang was head of domestic security and a member of the Communist Party Standing Politburo Committee, making him one of the most powerful people in China, until he stepped down in 2012. REUTERS/STRINGER Authorities have begun investigating a crash in 2000 that killed the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, the prime target in China’s biggest corruption scandal, Reuters source says. China turns up heat on ex-security chief with crash probe BY BENJAMIN KANG LIM, CHARLIE ZHU AND DAVID LAGUE SPECIAL REPORT 1 CHINA’S POWER STRUGGLE BEIJING/HONG KONG, SEPTEMBER 12, 2014 ittle is known about the exact circum- stances in which Wang Shuhua was Lkilled. What has been reported, in the Chinese media, is that she died in a road ac- cident sometime in 2000, shortly after she was divorced from her husband. And that at least one vehicle with a military license plate may have been involved in the crash. Fourteen years later, investigators are looking into her death. Their sudden inter- est has nothing to do with Wang herself. It has to do with the identity of her ex-hus- band – once one of China’s most powerful men and now the prime target in President Xi Jinping’s anti-corruption campaign. Investigators are probing the death of the first wife of Zhou Yongkang, China’s HUNTING TIGERS: President Xi Jinping has launched the biggest corruption crackdown since the retired security czar, a source with di- communists came to power in 1949, going after “tigers” or high-ranking officials as well as “flies”. -

Journal of Current Chinese Affairs

China Data Supplement March 2008 J People’s Republic of China J Hong Kong SAR J Macau SAR J Taiwan ISSN 0943-7533 China aktuell Data Supplement – PRC, Hong Kong SAR, Macau SAR, Taiwan 1 Contents The Main National Leadership of the PRC ......................................................................... 2 LIU Jen-Kai The Main Provincial Leadership of the PRC ..................................................................... 31 LIU Jen-Kai Data on Changes in PRC Main Leadership ...................................................................... 38 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Agreements with Foreign Countries ......................................................................... 54 LIU Jen-Kai PRC Laws and Regulations .............................................................................................. 56 LIU Jen-Kai Hong Kong SAR ................................................................................................................ 58 LIU Jen-Kai Macau SAR ....................................................................................................................... 65 LIU Jen-Kai Taiwan .............................................................................................................................. 69 LIU Jen-Kai ISSN 0943-7533 All information given here is derived from generally accessible sources. Publisher/Distributor: GIGA Institute of Asian Studies Rothenbaumchaussee 32 20148 Hamburg Germany Phone: +49 (0 40) 42 88 74-0 Fax: +49 (040) 4107945 2 March 2008 The Main National Leadership of the -

Introduction This Statement Is Submitted to the U.S.-China

USCC Hearing China’s Military Transition February 7, 2013 Roy Kamphausen Senior Advisor, The National Bureau of Asian Research Introduction This statement is submitted to the U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission to address issues related to the transition to the new top military leadership in China. The statement addresses the composition of the new Central Military Commission, important factors in the selection of the leaders, and highlights salient elements in the backgrounds of specific leaders. The statement also addresses important factors of civil-military relations, including the relationship of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) to China’s top political leadership, potential reform of the military-region structure of the PLA, and the likely competition for budget resources. Composition of the China’s New Central Military Commission As expected, new Chinese Communist Party general secretary Xi Jinping was appointed in November 2012 as the Central Military Commission (CMC) chairman. Additionally, army general Fan Changlong and air force general Xu Qiliang were promoted to positions as vice chairmen of the CMC—Fan from Jinan Military Region commander and Xu from PLA Air Force commander. Other members of the new CMC include General Chang Wanquan, who will become the next Minister of National Defense when that position is confirmed in early spring 2013; General Fang Fenghui, chief of the General Staff Department (GSD), who previously had been Beijing Military Region commander since 2007; General Zhang Yang, director of -

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles

The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles The Chinese Navy Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Saunders, EDITED BY Yung, Swaine, PhILLIP C. SAUNderS, ChrISToPher YUNG, and Yang MIChAeL Swaine, ANd ANdreW NIeN-dzU YANG CeNTer For The STUdY oF ChINeSe MilitarY AffairS INSTITUTe For NATIoNAL STrATeGIC STUdIeS NatioNAL deFeNSe UNIverSITY COVER 4 SPINE 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY COVER.indd 3 COVER 1 11/29/11 12:35 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 1 11/29/11 12:37 PM 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 2 11/29/11 12:37 PM The Chinese Navy: Expanding Capabilities, Evolving Roles Edited by Phillip C. Saunders, Christopher D. Yung, Michael Swaine, and Andrew Nien-Dzu Yang Published by National Defense University Press for the Center for the Study of Chinese Military Affairs Institute for National Strategic Studies Washington, D.C. 2011 990-219 NDU CHINESE NAVY.indb 3 11/29/11 12:37 PM Opinions, conclusions, and recommendations expressed or implied within are solely those of the contributors and do not necessarily represent the views of the U.S. Department of Defense or any other agency of the Federal Government. Cleared for public release; distribution unlimited. Chapter 5 was originally published as an article of the same title in Asian Security 5, no. 2 (2009), 144–169. Copyright © Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Chinese Navy : expanding capabilities, evolving roles / edited by Phillip C. Saunders ... [et al.]. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index.