Diversification of North American Natricine Snakes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xenosaurus Tzacualtipantecus. the Zacualtipán Knob-Scaled Lizard Is Endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of Eastern Mexico

Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus. The Zacualtipán knob-scaled lizard is endemic to the Sierra Madre Oriental of eastern Mexico. This medium-large lizard (female holotype measures 188 mm in total length) is known only from the vicinity of the type locality in eastern Hidalgo, at an elevation of 1,900 m in pine-oak forest, and a nearby locality at 2,000 m in northern Veracruz (Woolrich- Piña and Smith 2012). Xenosaurus tzacualtipantecus is thought to belong to the northern clade of the genus, which also contains X. newmanorum and X. platyceps (Bhullar 2011). As with its congeners, X. tzacualtipantecus is an inhabitant of crevices in limestone rocks. This species consumes beetles and lepidopteran larvae and gives birth to living young. The habitat of this lizard in the vicinity of the type locality is being deforested, and people in nearby towns have created an open garbage dump in this area. We determined its EVS as 17, in the middle of the high vulnerability category (see text for explanation), and its status by the IUCN and SEMAR- NAT presently are undetermined. This newly described endemic species is one of nine known species in the monogeneric family Xenosauridae, which is endemic to northern Mesoamerica (Mexico from Tamaulipas to Chiapas and into the montane portions of Alta Verapaz, Guatemala). All but one of these nine species is endemic to Mexico. Photo by Christian Berriozabal-Islas. amphibian-reptile-conservation.org 01 June 2013 | Volume 7 | Number 1 | e61 Copyright: © 2013 Wilson et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Com- mons Attribution–NonCommercial–NoDerivs 3.0 Unported License, which permits unrestricted use for non-com- Amphibian & Reptile Conservation 7(1): 1–47. -

Bibliography and Scientific Name Index to Amphibians

lb BIBLIOGRAPHY AND SCIENTIFIC NAME INDEX TO AMPHIBIANS AND REPTILES IN THE PUBLICATIONS OF THE BIOLOGICAL SOCIETY OF WASHINGTON BULLETIN 1-8, 1918-1988 AND PROCEEDINGS 1-100, 1882-1987 fi pp ERNEST A. LINER Houma, Louisiana SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE NO. 92 1992 SMITHSONIAN HERPETOLOGICAL INFORMATION SERVICE The SHIS series publishes and distributes translations, bibliographies, indices, and similar items judged useful to individuals interested in the biology of amphibians and reptiles, but unlikely to be published in the normal technical journals. Single copies are distributed free to interested individuals. Libraries, herpetological associations, and research laboratories are invited to exchange their publications with the Division of Amphibians and Reptiles. We wish to encourage individuals to share their bibliographies, translations, etc. with other herpetologists through the SHIS series. If you have such items please contact George Zug for instructions on preparation and submission. Contributors receive 50 free copies. Please address all requests for copies and inquiries to George Zug, Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, Washington DC 20560 USA. Please include a self-addressed mailing label with requests. INTRODUCTION The present alphabetical listing by author (s) covers all papers bearing on herpetology that have appeared in Volume 1-100, 1882-1987, of the Proceedings of the Biological Society of Washington and the four numbers of the Bulletin series concerning reference to amphibians and reptiles. From Volume 1 through 82 (in part) , the articles were issued as separates with only the volume number, page numbers and year printed on each. Articles in Volume 82 (in part) through 89 were issued with volume number, article number, page numbers and year. -

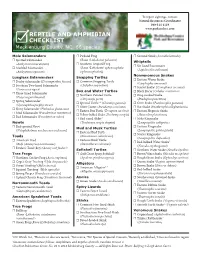

Checklist Reptile and Amphibian

To report sightings, contact: Natural Resources Coordinator 980-314-1119 www.parkandrec.com REPTILE AND AMPHIBIAN CHECKLIST Mecklenburg County, NC: 66 species Mole Salamanders ☐ Pickerel Frog ☐ Ground Skink (Scincella lateralis) ☐ Spotted Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) palustris) Whiptails (Ambystoma maculatum) ☐ Southern Leopard Frog ☐ Six-lined Racerunner ☐ Marbled Salamander (Rana (Lithobates) sphenocephala (Aspidoscelis sexlineata) (Ambystoma opacum) (sphenocephalus)) Nonvenomous Snakes Lungless Salamanders Snapping Turtles ☐ Eastern Worm Snake ☐ Dusky Salamander (Desmognathus fuscus) ☐ Common Snapping Turtle (Carphophis amoenus) ☐ Southern Two-lined Salamander (Chelydra serpentina) ☐ Scarlet Snake1 (Cemophora coccinea) (Eurycea cirrigera) Box and Water Turtles ☐ Black Racer (Coluber constrictor) ☐ Three-lined Salamander ☐ Northern Painted Turtle ☐ Ring-necked Snake (Eurycea guttolineata) (Chrysemys picta) (Diadophis punctatus) ☐ Spring Salamander ☐ Spotted Turtle2, 6 (Clemmys guttata) ☐ Corn Snake (Pantherophis guttatus) (Gyrinophilus porphyriticus) ☐ River Cooter (Pseudemys concinna) ☐ Rat Snake (Pantherophis alleghaniensis) ☐ Slimy Salamander (Plethodon glutinosus) ☐ Eastern Box Turtle (Terrapene carolina) ☐ Eastern Hognose Snake ☐ Mud Salamander (Pseudotriton montanus) ☐ Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta) (Heterodon platirhinos) ☐ Red Salamander (Pseudotriton ruber) ☐ Red-eared Slider3 ☐ Mole Kingsnake Newts (Trachemys scripta elegans) (Lampropeltis calligaster) ☐ Red-spotted Newt Mud and Musk Turtles ☐ Eastern Kingsnake -

211356675.Pdf

306.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE STORERIA DEKA YI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. and western Honduras. There apparently is a hiatus along the Suwannee River Valley in northern Florida, and also a discontin• CHRISTMAN,STEVENP. 1982. Storeria dekayi uous distribution in Central America . • FOSSILRECORD. Auffenberg (1963) and Gut and Ray (1963) Storeria dekayi (Holbrook) recorded Storeria cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean (pleisto• Brown snake cene) of Florida, and Holman (1962) listed S. cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean of Texas. Storeria sp. is reported from the Ir• Coluber Dekayi Holbrook, "1836" (probably 1839):121. Type-lo• vingtonian and Rancholabrean of Kansas (Brattstrom, 1967), and cality, "Massachusetts, New York, Michigan, Louisiana"; the Rancholabrean of Virginia (Guilday, 1962), and Pennsylvania restricted by Trapido (1944) to "Massachusetts," and by (Guilday et al., 1964; Richmond, 1964). Schmidt (1953) to "Cambridge, Massachusetts." See Re• • PERTINENT LITERATURE. Trapido (1944) wrote the most marks. Only known syntype (Acad. Natur. Sci. Philadelphia complete account of the species. Subsequent taxonomic contri• 5832) designated lectotype by Trapido (1944) and erroneously butions have included: Neill (195Oa), who considered S. victa a referred to as holotype by Malnate (1971); adult female, col• lector, and date unknown (not examined by author). subspecies of dekayi, Anderson (1961), who resurrected Cope's C[oluber] ordinatus: Storer, 1839:223 (part). S. tropica, and Sabath and Sabath (1969), who returned tropica to subspecific status. Stuart (1954), Bleakney (1958), Savage (1966), Tropidonotus Dekayi: Holbrook, 1842 Vol. IV:53. Paulson (1968), and Christman (1980) reported on variation and Tropidonotus occipito-maculatus: Holbrook, 1842:55 (inserted ad- zoogeography. Other distributional reports include: Carr (1940), denda slip). -

By a Nine-Banded Armadillo (Dasypus Novemcinctus) in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica

Edentata: in press Electronic version: ISSN 1852-9208 Print version: ISSN 1413-4411 http://www.xenarthrans.org FIELD NOTE Predation of a Central American coral snake (Micrurus nigrocinctus) by a nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) in Santa Rosa National Park, Costa Rica Eduardo CarrilloA and Todd K. FullerB,1 A Instituto Internacional en Conservación y Manejo de Vida Silvestre, Universidad Nacional, Apdo. 1350, Heredia, Costa Rica. E-mail: [email protected] B Department of Environmental Conservation, University of Massachusetts, Amherst, Massachusetts 01003, USA. E-mail: [email protected] 1 Corresponding author Abstract We describe the manner in which a nine-banded armadillo (Dasypus novemcinctus) killed a Cen- tral American coral snake (Micrurus nigrocinctus) that it subsequently ate. The armadillo repeatedly ran towards, jumped, flipped over in mid-air, and landed on top of the snake with its back until the snake was dead. Keywords: armadillo, behavior, food, predation, snake Depredación de una serpiente de coral de América Central (Micrurus nigrocinctus) por un armadillo de nueve bandas (Dasypus novemcinctus) en el Parque Nacional Santa Rosa, Costa Rica Resumen En esta nota describimos la manera en que un armadillo de nueve bandas (Dasypus novemcinc- tus) mató a una serpiente de coral de América Central (Micrurus nigrocinctus) que posteriormente comió. El armadillo corrió varias veces hacia adelante, saltó, se dio vuelta en el aire y aterrizó sobre la serpiente con la espalda hasta que la serpiente estuvo muerta. Palabras clave: armadillo, comida, comportamiento, depredación, serpiente Nine-banded armadillos (Dasypus novemcinc- The ~4-kg nine-banded armadillo is distributed tus) feed mostly on arthropods such as beetles, ter- from the southeast and central United States to Uru- mites, and ants, but also consume bird eggs and guay and northern Argentina, Granada, Trinidad “unusual items” such as fruits, fungi, and small verte- and Tobago, and the Margarita Islands (Loughry brates (McBee & Baker, 1982; Wetzel, 1991; Carrillo et al., 2014). -

Check List 17 (1): 27–38

17 1 ANNOTATED LIST OF SPECIES Check List 17 (1): 27–38 https://doi.org/10.15560/17.1.27 A herpetological survey of Edith L. Moore Nature Sanctuary Dillon Jones1, Bethany Foshee2, Lee Fitzgerald1 1 Biodiversity Research and Teaching Collections, Department of Ecology and Conservation Biology, Texas A&M University, College Station, TX, USA. 2 Houston Audubon, 440 Wilchester Blvd. Houston, TX 77079 USA. Corresponding author: Dillon Jones, [email protected] Abstract Urban herpetology deals with the interaction of amphibians and reptiles with each other and their environment in an ur- ban setting. As such, well-preserved natural areas within urban environments can be important tools for conservation. Edith L. Moore Nature Sanctuary is an 18-acre wooded sanctuary located west of downtown Houston, Texas and is the headquarters to Houston Audubon Society. This study compared iNaturalist data with results from visual encounter surveys and aquatic funnel traps. Results from these two sources showed 24 species belonging to 12 families and 17 genera of herpetofauna inhabit the property. However, several species common in surrounding areas were absent. Combination of data from community science and traditional survey methods allowed us to better highlight herpe- tofauna present in the park besides also identifying species that may be of management concern for Edith L. Moore. Keywords Community science, iNaturalist, urban herpetology Academic editor: Luisa Diele-Viegas | Received 27 August 2020 | Accepted 16 November 2020 | Published 6 January 2021 Citation: Jones D, Foshee B, Fitzgerald L (2021) A herpetology survey of Edith L. Moore Nature Sanctuary. Check List 17 (1): 27–28. https://doi. -

Indigenous and Established Herpetofauna of Northwest Louisiana

Indigenous and Established Herpetofauna of Northwest Louisiana Non-venomous Snakes (25 Species) For more info: Buttermilk Racer Coluber constrictor anthicus 318-773-9393 Eastern Coachwhip Coluber flagellum flagellum www.learnaboutcritters.org Prairie Kingsnake Lampropeltis calligaster [email protected] Speckled Kingsnake Lampropeltis holbrooki www.facebook.com/learnaboutcritters Western Milksnake Lampropeltis gentilis Northern Rough Greensnake Opheodrys aestivus aestivus Alligator (1 species) Western Ratsnake Pantherophis obsoletus American Alligator Alligator mississippiensis Slowinski’s Cornsnake † Pantherophis slowinskii Flat-headed Snake † Tantilla gracilis Western Wormsnake † Carphophis vermis Lizards (10 Species) Mississippi Ring-necked Snake Diadophis punctatus stictogenys Western Mudsnake Farancia abacura reinwardtii Northern Green Anole Anolis carolinensis Eastern Hog-nosed Snake Heterodon platirhinos Prairie Lizard Sceloporus consobrinus Mississippi Green Watersnake Nerodia cyclopion Southern Coal Skink † Plestiodon anthracinus pluvialis Plain-bellied Watersnake Nerodia erythrogaster Common Five-lined Skink Plestiodon fasciatus Broad-banded Watersnake Nerodia fasciata confluens Broad-headed Skink Plestiodon laticeps Graham's Crayfish Snake Regina grahamii Southern Prairie Skink † Plestiodon septentrionalis obtusirostris Gulf Swampsnake Liodytes rigida sinicola Little Brown Skink Scincella lateralis Dekay’s Brownsnake Storeria dekayi Eastern Six-lined Racerunner Aspidoscelis sexlineata sexlineata Red-bellied Snake -

Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA

GEOGRAPHIC DISTRIBUTION 597 Herpetological Review, 2015, 46(4), 597–601. © 2015 by Society for the Study of Amphibians and Reptiles Significant New Records of Amphibians and Reptiles from Georgia, USA Distributional maps found in Amphibians and Reptiles of records for a variety of amphibian and reptile species in Georgia. Georgia (Jensen et al. 2008), along with subsequent geographical All records below were verified by David Bechler (VSU), Nikole distribution notes published in Herpetological Review, serve Castleberry (GMNH), David Laurencio (AUM), Lance McBrayer as essential references for county-level occurrence data for (GSU), and David Steen (SRSU), and datum used was WGS84. herpetofauna in Georgia. Collectively, these resources aid Standard English names follow Crother (2012). biologists by helping to identify distributional gaps for which to target survey efforts. Herein we report newly documented county CAUDATA — SALAMANDERS DIRK J. STEVENSON AMBYSTOMA OPACUM (Marbled Salamander). CALHOUN CO.: CHRISTOPHER L. JENKINS 7.8 km W Leary (31.488749°N, 84.595917°W). 18 October 2014. D. KEVIN M. STOHLGREN Stevenson. GMNH 50875. LOWNDES CO.: Langdale Park, Valdosta The Orianne Society, 100 Phoenix Road, Athens, (30.878524°N, 83.317114°W). 3 April 1998. J. Evans. VSU C0015. Georgia 30605, USA First Georgia record for the Suwannee River drainage. MURRAY JOHN B. JENSEN* CO.: Conasauga Natural Area (34.845116°N, 84.848180°W). 12 Georgia Department of Natural Resources, 116 Rum November 2013. N. Klaus and C. Muise. GMNH 50548. Creek Drive, Forsyth, Georgia 31029, USA DAVID L. BECHLER Department of Biology, Valdosta State University, Valdosta, AMBYSTOMA TALPOIDEUM (Mole Salamander). BERRIEN CO.: Georgia 31602, USA St. -

Reptiles in Arkansas

Terrestrial Reptile Report Carphophis amoenus Co mmon Wor msnake Class: Reptilia Order: Serpentes Family: Colubridae Priority Score: 19 out of 100 Population Trend: Unknown Global Rank: G5 — Secure State Rank: S2 — Imperiled in Arkansas Distribution Occurrence Records Ecoregions where the species occurs: Ozark Highlands Boston Mountains Arkansas Valley Ouachita Mountains South Central Plains Mississippi Alluvial Plain Mississippi Valley Loess Plain Carphophis amoenus Common Wormsnake 1079 Terrestrial Reptile Report Habitat Map Habitats Weight Crowley's Ridge Loess Slope Forest Obligate Lower Mississippi Flatwoods Woodland and Forest Suitable Problems Faced KNOWN PROBLEM: Habitat loss due to conversion Threat: Habitat destruction or to agriculture. conversion Source: Agricultural practices KNOWN PROBLEM: Habitat loss due to forestry Threat: Habitat destruction or practices. conversion Source: Forestry activities Data Gaps/Research Needs Genetic analyses comparing Arkansas populations with populations east of the Mississippi River and the Western worm snake. Conservation Actions Importance Category More data are needed to determine conservation actions. Monitoring Strategies More information is needed to develop a monitoring strategy. Carphophis amoenus Common Wormsnake 1080 Terrestrial Reptile Report Comments Trauth and others (2004) summarized the literature and biology of this snake. In April 2005, two new geographic distribution records were collected in Loess Slope Forest habitat within St. Francis National Forest, south of the Mariana -

Class Reptilia

REPTILE CWCS SPECIES (27 SPECIES) Common name Scientific name Alligator Snapping Turtle Macrochelys temminckii Broad-banded Water Snake Nerodia fasciata confluens Coal Skink Eumeces anthracinus Copperbelly Watersnake Nerodia erythrogaster neglecta Corn Snake Elaphe guttata guttata Diamondback Water Snake Nerodia rhombifer rhombifer Eastern Coachwhip Masticophis flagellum flagellum Eastern Mud Turtle Kinosternon subrubrum Eastern Ribbon Snake Thamnophis sauritus sauritus Eastern Slender Glass Lizard Ophisaurus attenuatus longicaudus False Map Turtle Graptemys pseudogeographica pseudogeographica Green Water Snake Nerodia cyclopion Kirtland's Snake Clonophis kirtlandii Midland Smooth Softshell Apalone mutica mutica Mississippi Map Turtle Graptemys pseudogeographica kohnii Northern Pine Snake Pituophis melanoleucus melanoleucus Northern Scarlet Snake Cemophora coccinea copei Scarlet Kingsnake Lampropeltis triangulum elapsoides Six-lined Racerunner Cnemidophorus sexlineatus Southeastern Crowned Snake Tantilla coronata Southeastern Five-lined Skink Eumeces inexpectatus Southern Painted Turtle Chrysemys picta dorsalis Timber Rattlesnake Crotalus horridus Western Cottonmouth Agkistrodon piscivorus leucostoma Western Mud Snake Farancia abacura reinwardtii Western Pygmy Rattlesnake Sistrurus miliarius streckeri Western Ribbon Snake Thamnophis proximus proximus CLASS REPTILIA Alligator Snapping Turtle Macrochelys temminckii Federal Heritage GRank SRank GRank SRank Status Status (Simplified) (Simplified) N T G3G4 S2 G3 S2 G-Trend Decreasing G-Trend -

Graham's Crayfish Snake Regina Grahamii

Graham’s crayfish snake Regina grahamii Kingdom: Animalia FEATURES Phylum: Chordata Graham’s crayfish snake averages 18 to 28 inches in Class: Reptilia length. Its back is brown or dark olive, and a broad, Order: Squamata yellow stripe is present along each lower side. The belly is yellow and may or may not have markings. Family: Natricidae The scales are keeled (ridged). ILLINOIS STATUS common, native BEHAVIORS Graham’s crayfish snake may be found throughout © Scott Ballard Illinois except in those counties that border the Wabash and Ohio rivers. It is not abundant in any area. This snake lives in ponds, streams, sloughs, swamps and marshes. Graham’s crayfish snake is semiaquatic. It hides under stones or debris along the water’s edge and sometimes in crayfish burrows or other burrows. It basks on rocks and in branches overhanging the water. It is active in the day except in the hot summer months when it becomes nocturnal. This snake may flatten its body when disturbed and/or release large amounts of bad- adult smelling musk from glands at the base of the tail. It overwinters in crayfish burrows or other burrows. Mating occurs in April or May. The female gives birth to from 10 to 20 young in late summer, the number depending on her size and age. Graham’s crayfish snake mainly eats crayfish that have just shed their exoskeleton but will also take other crustaceans, ILLINOIS RANGE amphibians and fishes. © U.S. Army Corps of Engineers © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. 2021. Biodiversity of Illinois. Unless otherwise noted, photos and images © Illinois Department of Natural Resources. -

Notice Warning Concerning Copyright Restrictions P.O

Publisher of Journal of Herpetology, Herpetological Review, Herpetological Circulars, Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles, and three series of books, Facsimile Reprints in Herpetology, Contributions to Herpetology, and Herpetological Conservation Officers and Editors for 2015-2016 President AARON BAUER Department of Biology Villanova University Villanova, PA 19085, USA President-Elect RICK SHINE School of Biological Sciences University of Sydney Sydney, AUSTRALIA Secretary MARION PREEST Keck Science Department The Claremont Colleges Claremont, CA 91711, USA Treasurer ANN PATERSON Department of Natural Science Williams Baptist College Walnut Ridge, AR 72476, USA Publications Secretary BRECK BARTHOLOMEW Notice warning concerning copyright restrictions P.O. Box 58517 Salt Lake City, UT 84158, USA Immediate Past-President ROBERT ALDRIDGE Saint Louis University St Louis, MO 63013, USA Directors (Class and Category) ROBIN ANDREWS (2018 R) Virginia Polytechnic and State University, USA FRANK BURBRINK (2016 R) College of Staten Island, USA ALISON CREE (2016 Non-US) University of Otago, NEW ZEALAND TONY GAMBLE (2018 Mem. at-Large) University of Minnesota, USA LISA HAZARD (2016 R) Montclair State University, USA KIM LOVICH (2018 Cons) San Diego Zoo Global, USA EMILY TAYLOR (2018 R) California Polytechnic State University, USA GREGORY WATKINS-COLWELL (2016 R) Yale Peabody Mus. of Nat. Hist., USA Trustee GEORGE PISANI University of Kansas, USA Journal of Herpetology PAUL BARTELT, Co-Editor Waldorf College Forest City, IA 50436, USA TIFFANY