Great Dismal Swamp Northern Brown Snake

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices

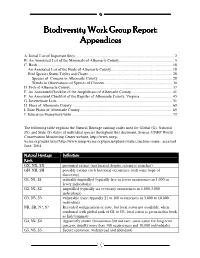

Biodiversity Work Group Report: Appendices A: Initial List of Important Sites..................................................................................................... 2 B: An Annotated List of the Mammals of Albemarle County........................................................ 5 C: Birds ......................................................................................................................................... 18 An Annotated List of the Birds of Albemarle County.............................................................. 18 Bird Species Status Tables and Charts...................................................................................... 28 Species of Concern in Albemarle County............................................................................ 28 Trends in Observations of Species of Concern..................................................................... 30 D. Fish of Albemarle County........................................................................................................ 37 E. An Annotated Checklist of the Amphibians of Albemarle County.......................................... 41 F. An Annotated Checklist of the Reptiles of Albemarle County, Virginia................................. 45 G. Invertebrate Lists...................................................................................................................... 51 H. Flora of Albemarle County ...................................................................................................... 69 I. Rare -

Herpetological Review

Herpetological Review FARANCIA ERYTROGRAMMA (Rainbow Snake). HABITAT. Submitted by STAN J. HUTCHENS (e-mail: [email protected]) and CHRISTOPHER S. DEPERNO, (e-mail: [email protected]), Fisheries and Wildlife Pro- gram, North Carolina State University, 110 Brooks Ave., Raleigh, North Carolina 27607, USA. canadensis) dams reduced what little fl ow existed in some canals to standing quagmires more representative of the habitat selected by Eastern Mudsnakes (Farancia abacura; Neill 1964, op. cit.). Interestingly, one A. rostrata was observed near BNS, but none was captured within the swamp. It is possible that Rainbow Snakes leave bordering fl uvial habitats in pursuit of young eels that wan- dered into canals and swamp habitats. Capturing such a secretive and uncommon species as F. ery- trogramma in unexpected habitat encourages consideration of their delicate ecological niche. Declining population indices for American Eels along the eastern United States are attributed to overfi shing, parasitism, habitat loss, pollution, and changes in major currents related to climate change (Hightower and Nesnow 2006. Southeast. Nat. 5:693–710). Eel declines could negatively impact population sizes and distributions of Rainbow Snakes, especially in inland areas. We believe future studies based on con- fi rmed Rainbow Snake occurrences from museum records or North Carolina GAP data could better delineate the range within North Carolina. Additionally, sampling for American Eels to determine their population status and distribution in North Carolina could augment population and distribution data for Rainbow Snakes. We thank A. Braswell, J. Jensen, and P. Moler for comments on earlier drafts of this manuscript. Submitted by STAN J. HUTCHENS (e-mail: [email protected]) and CHRISTOPHER S. -

Butterflies of the Wesleyan Campus

BUTTERFLIES OF THE WESLEYAN CAMPUS SWALLOWTAILS Hairstreaks (Subfamily - Theclinae) (Family PAPILIONIDAE) Great Purple Hairstreak - Atlides halesus Coral Hairstreak - Satyrium titus True Swallowtails Banded Hairstreak - Satyrium calanus (Subfamily - Papilioninae) Striped Hairstreak - Satyrium liparops Pipevine Swallowtail - Battus philenor Henry’s Elfin - Callophrys henrici Zebra Swallowtail - Eurytides marcellus Eastern Pine Elfin - Callophrys niphon Black Swallowtail - Papilio polyxenes Juniper Hairstreak - Callophrys gryneus Giant Swallowtail - Papilio cresphontes White M Hairstreak - Parrhasius m-album Eastern Tiger Swallowtail - Papilio glaucus Gray Hairstreak - Strymon melinus Spicebush Swallowtail - Papilio troilus Red-banded Hairstreak - Calycopis cecrops Palamedes Swallowtail - Papilio palamedes Blues (Subfamily - Polommatinae) Ceraunus Blue - Hemiargus ceraunus Eastern-Tailed Blue - Everes comyntas WHITES AND SULPHURS Spring Azure - Celastrina ladon (Family PIERIDAE) Whites (Subfamily - Pierinae) BRUSHFOOTS Cabbage White - Pieris rapae (Family NYMPHALIDAE) Falcate Orangetip - Anthocharis midea Snouts (Subfamily - Libytheinae) American Snout - Libytheana carinenta Sulphurs and Yellows (Subfamily - Coliadinae) Clouded Sulphur - Colias philodice Heliconians and Fritillaries Orange Sulphur - Colias eurytheme (Subfamily - Heliconiinae) Southern Dogface - Colias cesonia Gulf Fritillary - Agraulis vanillae Cloudless Sulphur - Phoebis sennae Zebra Heliconian - Heliconius charithonia Barred Yellow - Eurema daira Variegated Fritillary -

Rare Native Animals of RI

RARE NATIVE ANIMALS OF RHODE ISLAND Revised: March, 2006 ABOUT THIS LIST The list is divided by vertebrates and invertebrates and is arranged taxonomically according to the recognized authority cited before each group. Appropriate synonomy is included where names have changed since publication of the cited authority. The Natural Heritage Program's Rare Native Plants of Rhode Island includes an estimate of the number of "extant populations" for each listed plant species, a figure which has been helpful in assessing the health of each species. Because animals are mobile, some exhibiting annual long-distance migrations, it is not possible to derive a population index that can be applied to all animal groups. The status assigned to each species (see definitions below) provides some indication of its range, relative abundance, and vulnerability to decline. More specific and pertinent data is available from the Natural Heritage Program, the Rhode Island Endangered Species Program, and the Rhode Island Natural History Survey. STATUS. The status of each species is designated by letter codes as defined: (FE) Federally Endangered (7 species currently listed) (FT) Federally Threatened (2 species currently listed) (SE) State Endangered Native species in imminent danger of extirpation from Rhode Island. These taxa may meet one or more of the following criteria: 1. Formerly considered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service for Federal listing as endangered or threatened. 2. Known from an estimated 1-2 total populations in the state. 3. Apparently globally rare or threatened; estimated at 100 or fewer populations range-wide. Animals listed as State Endangered are protected under the provisions of the Rhode Island State Endangered Species Act, Title 20 of the General Laws of the State of Rhode Island. -

Yellow-Bellied Water Snake Plain-Bellied Water

Nature Flashcards Snakes All photos are subject to the terms of the Creative Commons Public License Based on Nature Quiz Attribution-Non-Commercial 3.0 United States unless copyright otherwise By Phil Huxford noted. TMN-COT Meeting November, 2013 Texas Master Naturalist Cradle of Texas Chapter Cradle of Texas Chapter Yellow-bellied Water Snake Plain-bellied Water Snake Nerodia erythrogaster flavigaster Elliptical eye pupils Bright yellow underneath Found around ponds, lakes, swamps, and wet bottomland forests 2 – 3 feet long Cradle of Texas Chapter Broad-banded Water snake Nerodia fasciata confluens Dark, wide bands separated by yellow Bold, dark checked stripes Strong swimmer Cradle of Texas Chapter 2 – 4 feet long Blotched Water Snake Nerodia erythrogaster transversa Black-edged; dark brown dorsal markings Yellow or sometimes orange belly Lives in small ponds, ditches, and rain-filled pools Typically 2 – 5 feet long Cradle of Texas Chapter Diamond-back Water Snake Northern Diamond-back Water Snake Nerodia rhombifer Heavy-bodied, large girth Can be dark brown Head somewhat flattened and wide Texas’ largest Nerodia Strikes without warning and viciously 4 – 6’ long Cradle of Texas Chapter Photo by J.D. Wilson http://srelherp.uga.edu/snakes/ Western Mud Snake Mud Snake Farancia abacura Lives in our area but rarely seen Glossy black above Red belly with black lines in belly Found in wooded swampland and wet areas Does not bite when handled but pokes tail like stinger 3 – 4 feet long Cradle of Texas Chapter Texas Coral Snake Micrurus fulvius tenere Blunt head; shiny, slender body Round pupils Colors red, yellow, black Lives in partly wooded organic material Cradle of Texas Chapter Usually 2 – 3 feet long Record: 47 ¾ inches in Brazoria County ‘Red touches yellow – kill a fellow. -

Contributions of Intensively Managed Forests to the Sustainability of Wildlife Communities in the South

CONTRIBUTIONS OF INTENSIVELY MANAGED FORESTS TO THE SUSTAINABILITY OF WILDLIFE COMMUNITIES IN THE SOUTH T. Bently Wigley1, William M. Baughman, Michael E. Dorcas, John A. Gerwin, J. Whitfield Gibbons, David C. Guynn, Jr., Richard A. Lancia, Yale A. Leiden, Michael S. Mitchell, Kevin R. Russell ABSTRACT Wildlife communities in the South are increasingly influenced by land use changes associated with human population growth and changes in forest management strategies on both public and private lands. Management of industry-owned landscapes typically results in a diverse mixture of habitat types and spatial arrangements that simultaneously offers opportunities to maintain forest cover, address concerns about fragmentation, and provide habitats for a variety of wildlife species. We report here on several recent studies of breeding bird and herpetofaunal communities in industry-managed landscapes in South Carolina. Study landscapes included the 8,100-ha GilesBay/Woodbury Tract, owned and managed by International Paper Company, and 62,363-ha of the Ashley and Edisto Districts, owned and managed by Westvaco Corporation. Breeding birds were sampled in both landscapes from 1995-1999 using point counts, mist netting, nest searching, and territory mapping. A broad survey of herpetofauna was conducted during 1996-1998 across the Giles Bay/Woodbury Tract using a variety of methods, including: searches of natural cover objects, time-constrained searches, drift fences with pitfall traps, coverboards, automated recording systems, minnow traps, and turtle traps. Herpetofaunal communities were sampled more intensively in both landscapes during 1997-1999 in isolated wetland and selected structural classes. The study landscapes supported approximately 70 bird and 72 herpetofaunal species, some of which are of conservation concern. -

Cottonmouth Snake Bites Reported to the Toxic North American Snakebite Registry 2013–2017

Clinical Toxicology ISSN: 1556-3650 (Print) 1556-9519 (Online) Journal homepage: https://www.tandfonline.com/loi/ictx20 Cottonmouth snake bites reported to the ToxIC North American snakebite registry 2013–2017 K. Domanski, K. C. Kleinschmidt, S. Greene, A. M. Ruha, V. Berbata, N. Onisko, S. Campleman, J. Brent, P. Wax & on behalf of the ToxIC North American Snakebite Registry Group To cite this article: K. Domanski, K. C. Kleinschmidt, S. Greene, A. M. Ruha, V. Berbata, N. Onisko, S. Campleman, J. Brent, P. Wax & on behalf of the ToxIC North American Snakebite Registry Group (2019): Cottonmouth snake bites reported to the ToxIC North American snakebite registry 2013–2017, Clinical Toxicology, DOI: 10.1080/15563650.2019.1627367 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2019.1627367 Published online: 13 Jun 2019. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 38 View Crossmark data Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at https://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=ictx20 CLINICAL TOXICOLOGY https://doi.org/10.1080/15563650.2019.1627367 CLINICAL RESEARCH Cottonmouth snake bites reported to the ToxIC North American snakebite registry 2013–2017 K. Domanskia, K. C. Kleinschmidtb, S. Greenec , A. M. Ruhad, V. Berbatae, N. Oniskob, S. Camplemanf, J. Brente, P. Waxb and on behalf of the ToxIC North American Snakebite Registry Group aReno School of Medicine, University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA; bSouthwestern Medical Center, University of Texas, Dallas, TX, USA; cBaylor College of Medicine, Houston, TX, USA; dBanner Good Samaritan Medical Center, Phoenix, AZ, USA; eEmergency Medicine, Medical Toxicology, University of Colorado, Denver, CO, USA; fAmerican College of Medical Toxicology, Phoenix, AZ, USA ABSTRACT ARTICLE HISTORY Introduction: The majority of venomous snake exposures in the United States are due to snakes from Received 9 April 2019 the subfamily Crotalinae (pit vipers). -

211356675.Pdf

306.1 REPTILIA: SQUAMATA: SERPENTES: COLUBRIDAE STORERIA DEKA YI Catalogue of American Amphibians and Reptiles. and western Honduras. There apparently is a hiatus along the Suwannee River Valley in northern Florida, and also a discontin• CHRISTMAN,STEVENP. 1982. Storeria dekayi uous distribution in Central America . • FOSSILRECORD. Auffenberg (1963) and Gut and Ray (1963) Storeria dekayi (Holbrook) recorded Storeria cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean (pleisto• Brown snake cene) of Florida, and Holman (1962) listed S. cf. dekayi from the Rancholabrean of Texas. Storeria sp. is reported from the Ir• Coluber Dekayi Holbrook, "1836" (probably 1839):121. Type-lo• vingtonian and Rancholabrean of Kansas (Brattstrom, 1967), and cality, "Massachusetts, New York, Michigan, Louisiana"; the Rancholabrean of Virginia (Guilday, 1962), and Pennsylvania restricted by Trapido (1944) to "Massachusetts," and by (Guilday et al., 1964; Richmond, 1964). Schmidt (1953) to "Cambridge, Massachusetts." See Re• • PERTINENT LITERATURE. Trapido (1944) wrote the most marks. Only known syntype (Acad. Natur. Sci. Philadelphia complete account of the species. Subsequent taxonomic contri• 5832) designated lectotype by Trapido (1944) and erroneously butions have included: Neill (195Oa), who considered S. victa a referred to as holotype by Malnate (1971); adult female, col• lector, and date unknown (not examined by author). subspecies of dekayi, Anderson (1961), who resurrected Cope's C[oluber] ordinatus: Storer, 1839:223 (part). S. tropica, and Sabath and Sabath (1969), who returned tropica to subspecific status. Stuart (1954), Bleakney (1958), Savage (1966), Tropidonotus Dekayi: Holbrook, 1842 Vol. IV:53. Paulson (1968), and Christman (1980) reported on variation and Tropidonotus occipito-maculatus: Holbrook, 1842:55 (inserted ad- zoogeography. Other distributional reports include: Carr (1940), denda slip). -

TPWD White List

TPWD White List Frogs and Toads Great Plains toad (Bufo cognatus) Green toad (Bufo debilis) Red-spotted toad (Bufo punctatus) Texas toad (Bufo speciosus) Gulf Coast toad (Bufo valliceps) Woodhouse’s toad (Bufo woodhousei) Green treefrog (Hyla cinerea) Bull frog (Rana catesbeiana) Couch’s spadefoot (Scaphiopus couchii) Plains spadefoot (Spea bombifrons) New Mexico spadefoot (Spea multiplicata) Salamanders Tiger salamander (Ambystoma tigrinum) Lizards Green anole (Anolis carolinensis) Chihuahuan spotted whiptail (Aspidoscelis exsanguis) Texas spotted whiptail (Aspidoscelis gularis) Marbled whiptail (Aspidoscelis marmoratus) Six-lined racerunner (Aspidoscelis sexlineatus) Checkered whiptail (Aspidoscelis tesselatus) Texas banded gecko (Coleonyx brevis) Greater earless lizard (Cophosaurus texanus) Collared lizard (Crotaphytus collaris) Five-lined skink (Eumeces fasciatus) Great plains skink (Eumeces obsoletus) Texas alligator lizard (Gerrhonotus infernalis) Lesser earless lizard (Holbrookia maculata) Crevice spiny lizard (Sceloporus poinsettii) Prairie lizard (Sceloporus undulatus) Ground skink (Scincella lateralis) Tree lizard (Urosaurus ornatus) Side-blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana) Snakes Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix) Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorus) Glossy snake (Arizona elegans) Trans-Pecos rat snake (Bogertophis subocularis) Racer (Coluber constrictor) Western diamondback rattlesnake (Crotalus atrox) Rock rattlesnake (Crotalus lepidus) Blacktail rattlesnake (Crotalus molossus) Mojave rattlesnake (Crotalus scutulatus) Prairie -

Marine Reptiles Arne R

Virginia Commonwealth University VCU Scholars Compass Study of Biological Complexity Publications Center for the Study of Biological Complexity 2011 Marine Reptiles Arne R. Rasmessen The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts John D. Murphy Field Museum of Natural History Medy Ompi Sam Ratulangi University J. Whitfield iG bbons University of Georgia Peter Uetz Virginia Commonwealth University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/csbc_pubs Part of the Life Sciences Commons Copyright: © 2011 Rasmussen et al. This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original author and source are credited. Downloaded from http://scholarscompass.vcu.edu/csbc_pubs/20 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Center for the Study of Biological Complexity at VCU Scholars Compass. It has been accepted for inclusion in Study of Biological Complexity Publications by an authorized administrator of VCU Scholars Compass. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Review Marine Reptiles Arne Redsted Rasmussen1, John C. Murphy2, Medy Ompi3, J. Whitfield Gibbons4, Peter Uetz5* 1 School of Conservation, The Royal Danish Academy of Fine Arts, Copenhagen, Denmark, 2 Division of Amphibians and Reptiles, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago, Illinois, United States of America, 3 Marine Biology Laboratory, Faculty of Fisheries and Marine Sciences, Sam Ratulangi University, Manado, North Sulawesi, Indonesia, 4 Savannah River Ecology Lab, University of Georgia, Aiken, South Carolina, United States of America, 5 Center for the Study of Biological Complexity, Virginia Commonwealth University, Richmond, Virginia, United States of America Of the more than 12,000 species and subspecies of extant Caribbean, although some species occasionally travel as far north reptiles, about 100 have re-entered the ocean. -

Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L

CIR1462 Snakes of the Everglades Agricultural Area1 Michelle L. Casler, Elise V. Pearlstine, Frank J. Mazzotti, and Kenneth L. Krysko2 Background snakes are often escapees or are released deliberately and illegally by owners who can no longer care for them. Snakes are members of the vertebrate order Squamata However, there has been no documentation of these snakes (suborder Serpentes) and are most closely related to lizards breeding in the EAA (Tennant 1997). (suborder Sauria). All snakes are legless and have elongated trunks. They can be found in a variety of habitats and are able to climb trees; swim through streams, lakes, or oceans; Benefits of Snakes and move across sand or through leaf litter in a forest. Snakes are an important part of the environment and play Often secretive, they rely on scent rather than vision for a role in keeping the balance of nature. They aid in the social and predatory behaviors. A snake’s skull is highly control of rodents and invertebrates. Also, some snakes modified and has a great degree of flexibility, called cranial prey on other snakes. The Florida kingsnake (Lampropeltis kinesis, that allows it to swallow prey much larger than its getula floridana), for example, prefers snakes as prey and head. will even eat venomous species. Snakes also provide a food source for other animals such as birds and alligators. Of the 45 snake species (70 subspecies) that occur through- out Florida, 23 may be found in the Everglades Agricultural Snake Conservation Area (EAA). Of the 23, only four are venomous. The venomous species that may occur in the EAA are the coral Loss of habitat is the most significant problem facing many snake (Micrurus fulvius fulvius), Florida cottonmouth wildlife species in Florida, snakes included. -

What Typical Population Density Could You Expect for the Species in a Hectare of Ideal Habitat?

SQUAMATES DENSITY - What typical population density could you expect for the species in a hectare of ideal habitat? Species Common Name Density Sauria Lizards Anguidae Anguid Lizards Ophisaurus attenuatus longicaudus Eastern Slender Glass Lizard >400 / ha; 4-111/ ha (Fitch 1989) Ophisaurus ventralis Eastern Glass Lizard Unk Lacertidae Wall Lizards Podarcis sicula Italian Wall Lizard Unk Phrynosomatidae Sceloporine Lizards Sceloporus undulatus hyacinthinus Northern Fence Lizard Unk Scincidae Skinks Eumeces a. anthracinus Northern Coal Skink Unk Eumeces fasciatus Common Five-lined Skink 85 / ha (Klemens 1993) Eumeces inexpectatus Southeastern Five-lined Skink Unk Eumeces laticeps Broad-headed Skink Unk Scincella lateralis Ground Skink 400-1500 / ha (Brooks 1967) Teiidae Whiptails Cnemidophorus s. sexlineatus Eastern Six-lined Racerunner 2.5 / 100 m2 (Mitchell 1994) Colubridae Colubrids Carphophis a. amoenus Eastern Worm Snake 60 - 120 / ha in KS (Clark 1970) Cemophora coccinea copei Northern Scarlet Snake Unk Clonophis kirtlandii Kirtland's Snake 19 along 0.6 km street (Minton 1972) Coluber c. constrictor Northern Black Racer 1-3 / ha (Ernst, pers. obs.); 3-7 / ha (Fitch 1963b) Diadophis p. punctatus Southern Ringneck Snake 719-1,849 / ha (Fitch 1975); > 100 / ha (Hulse, pers. obs.) Diadophis p. edwardsii Northern Ringneck Snake 719-1,849 / ha (Fitch 1975); > 100 / ha (Hulse, pers. obs.) Elaphe guttata Corn Snake less than 1 / 100 ha in KS (Fitch 1958a) Elaphe o. obsoleta Black Rat Snake 0.23 / ha MD (Stickel et al. 1980); 1 / ha in KS (Fitch 1963a) Farancia a. abacura Eastern Mud Snake about 150 / km (Hellman and Telford 1956) Farancia e. erytrogramma Common Rainbow Snake 8 in 30 m (Mount 1975); 20 in 4.1 ha (Richmond 1945) Heterodon platirhinos Eastern Hog-nosed Snake 2.1 / ha (Platt 1969); 4.8 / ha in VA (Scott 1986) Lampropeltis calligaster Mole Kingsnake 1 / 2.6 ha (Ernst and Barbour 1989) rhombomaculata Lampropeltis g.