Syria: from Non-Religious and Democratic Revolution to ISIS Fabrice Balanche

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Offensive Against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area Near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS

June 23, 2016 Offensive against the Syrian City of Manbij May Be the Beginning of a Campaign to Liberate the Area near the Syrian-Turkish Border from ISIS Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) fighters at the western entrance to the city of Manbij (Fars, June 18, 2016). Overview 1. On May 31, 2016, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a Kurdish-dominated military alliance supported by the United States, initiated a campaign to liberate the northern Syrian city of Manbij from ISIS. Manbij lies west of the Euphrates, about 35 kilometers (about 22 miles) south of the Syrian-Turkish border. In the three weeks since the offensive began, the SDF forces, which number several thousand, captured the rural regions around Manbij, encircled the city and invaded it. According to reports, on June 19, 2016, an SDF force entered Manbij and occupied one of the key squares at the western entrance to the city. 2. The declared objective of the ground offensive is to occupy Manbij. However, the objective of the entire campaign may be to liberate the cities of Manbij, Jarabulus, Al-Bab and Al-Rai, which lie to the west of the Euphrates and are ISIS strongholds near the Turkish border. For ISIS, the loss of the area is liable to be a severe blow to its logistic links between the outside world and the centers of its control in eastern Syria (Al-Raqqah), Iraq (Mosul). Moreover, the loss of the region will further 112-16 112-16 2 2 weaken ISIS's standing in northern Syria and strengthen the military-political position and image of the Kurdish forces leading the anti-ISIS ground offensive. -

Bulletin De Liaison Et D'information

INSTITUT KUDE RPARD IS E Bulletin de liaison et d’information N°364 JUILLET 2015 La publication de ce Bulletin bénéficie de subventions du Ministère français des Affaires étrangères (DGCID) et du Fonds d’action et de soutien pour l’intégration et la lutte contre les discriminations (FASILD) ————— Ce bulletin paraît en français et anglais Prix au numéro : France: 6 € — Etranger : 7,5 € Abonnement annuel (12 numéros) France : 60 € — Etranger : 75 € Périodique mensuel Directeur de la publication : Mohamad HASSAN Numéro de la Commission Paritaire : 659 13 A.S. ISBN 0761 1285 INSTITUT KURDE, 106, rue La Fayette - 75010 PARIS Tél. : 01- 48 24 64 64 - Fax : 01- 48 24 64 66 www.fikp.org E-mail: [email protected] Bulletin de liaison et d’information de l’Institut kurde de Paris N° 364 juillet 2015 • TURQUIE : VERS LA FIN DU PROCESSUS DU PAIX ? • SYRIE : LES KURDES FONT RECULER LE DAESH • KURDISTAN : POINT SUR LA GUERRE CONTRE LE DAESH • PARIS : MORT DU PEINTRE REMZI • CULTURE : LECTURES POUR L’ÉTÉ TURQUIE : VERS LA FIN DU PROCESSUS DU PAIX ? près le succès électoral GAP) élaboré dans les années Mais le projet du GAP ne datant du HDP, en juin der - 1970, prévoit la construction de pas d’hier, la déclaration du A nier, la situation sécuri - 22 barrages sur les bassins du KCK envisageant de reprendre taire au Kurdistan de Tigre et de l’ Euphrate , afin d’irri - les combats si d’autres barrages Turquie s’est dégradée guer 1,7 million d’hectares de étaient construits, doit plutôt être avec une telle violence que le terres et de fournir 746 MW four - considérée comme une réaction processus de paix initié par nis par 19 centrales hydroélec - de « l’aile dure » du PKK, cher - Öcalan et l’AKP en mars 2013 a triques . -

The United States and Russian Governments Involvement in the Syrian Crisis and the United Nations’ Kofi Annan Peace Process

ISSN 2039-2117 (online) Mediterranean Journal of Social Sciences Vol 5 No 27 ISSN 2039-9340 (print) MCSER Publishing, Rome-Italy December 2014 The United States and Russian Governments Involvement in the Syrian Crisis and the United Nations’ Kofi Annan Peace Process Ken Ifesinachi Ph.D Professor of Political Science, University of Nigeria [email protected] Raymond Adibe Department of Political Science, University of Nigeria [email protected] Doi:10.5901/mjss.2014.v5n27p1154 Abstract The inability of the Syrian government to internally manage the popular uprising in the country have increased international pressure on Syria as well as deepen international efforts to resolve the crisis that has developed into a full scale civil war. It was the need to end the violent conflict in Syria that informed the appointment of Kofi Annan as the U.N-Arab League Special Envoy to Syria on February 23, 2012. This study investigates the U.S and Russian governments’ involvement in the Syrian crisis and the UN Kofi Annan peace process. The two persons’ Zero-sum model of the game theory is used as our framework of analysis. Our findings showed that the divergence on financial and military support by the U.S and Russian governments to the rival parties in the Syrian conflict contradicted the mandate of the U.N Security Council that sanctioned the Annan plan and compromised the ceasefire agreement contained in the plan which resulted in the escalation of violent conflict in Syria during the period the peace deal was supposed to be in effect. The implication of the study is that the success of any U.N brokered peace deal is highly dependent on the ability of its key members to have a consensus, hence, there is need to galvanize a comprehensive international consensus on how to tackle the Syrian crisis that would accommodate all crucial international actors. -

Syrian Jihadists Signal Intent for Lebanon

Jennifer Cafarella Backgrounder March 5, 2015 SYRIAN JIHADISTS SIGNAL INTENT FOR LEBANON Both the Islamic State of Iraq and al-Sham (ISIS) and the al-Qaeda affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra (JN) plan to conduct attacks in Lebanon in the near term. Widely presumed to be enemies, recent reports of an upcoming joint JN and ISIS offensive in Lebanon, when coupled with ongoing incidents of cooperation between these groups, indicate that the situation between these groups in Lebanon is as fluid and complicated as in Syria. Although they are direct competitors that have engaged in violent confrontation in other areas, JN and ISIS have co-existed in the Syrian-Lebanese border region since 2013, and their underground networks in southern and western Lebanon may overlap in ways that shape their local relationship. JN and ISIS are each likely to pursue future military operations in Lebanon that serve separate but complementary objectives. Since 2013 both groups have occasionally shown a willingness to cooperate in a limited fashion in order to capitalize on their similar objectives in Lebanon. This unusual relationship appears to be unique to Lebanon and the border region, and does not extend to other battlefronts. Despite recent clashes that likely strained this relationship in February 2015, contention between the groups in this area has not escalated beyond localized skirmishes. This suggests that both parties have a mutual interest in preserving their coexistence in this strategically significant area. In January 2015, JN initiated a new campaign of spectacular attacks against Lebanese supporters of the Syrian regime, while ISIS has increased its mobilization in the border region since airstrikes against ISIS in Syria began in September 2014. -

Télécharger Le COI Focus

COMMISSARIAT GÉNÉRAL AUX RÉFUGIÉS ET AUX APATRIDES COI Focus LIBAN La situation sécuritaire 7 août 2018 (Mise à jour) Cedoca Langue du document original : néerlandais DISCLAIMER: Ce document COI a été rédigé par le Centre de documentation et de This COI-product has been written by Cedoca, the Documentation and recherches (Cedoca) du CGRA en vue de fournir des informations pour le Research Department of the CGRS, and it provides information for the traitement des demandes d’asile individuelles. Il ne traduit aucune politique processing of individual asylum applications. The document does not contain ni n’exprime aucune opinion et ne prétend pas apporter de réponse définitive policy guidelines or opinions and does not pass judgment on the merits of quant à la valeur d’une demande d’asile. Il a été rédigé conformément aux the asylum application. It follows the Common EU Guidelines for processing lignes directrices de l’Union européenne pour le traitement de l’information country of origin information (April 2008). sur le pays d’origine (avril 2008) et il a été rédigé conformément aux The author has based the text on a wide range of public information selected dispositions légales en vigueur. with care and with a permanent concern for crosschecking sources. Even Ce document a été élaboré sur la base d’un large éventail d’informations though the document tries to Even though the document tries to cover all the publiques soigneusement sélectionnées dans un souci permanent de relevant aspects of the subject, the text is not necessarily exhaustive. If recoupement des sources. L’auteur s’est efforcé de traiter la totalité des certain events, people or organisations are not mentioned, this does not aspects pertinents du sujet mais les analyses proposées ne visent pas mean that they did not exist. -

Policy Notes for the Trump Notes Administration the Washington Institute for Near East Policy ■ 2018 ■ Pn55

TRANSITION 2017 POLICYPOLICY NOTES FOR THE TRUMP NOTES ADMINISTRATION THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ 2018 ■ PN55 TUNISIAN FOREIGN FIGHTERS IN IRAQ AND SYRIA AARON Y. ZELIN Tunisia should really open its embassy in Raqqa, not Damascus. That’s where its people are. —ABU KHALED, AN ISLAMIC STATE SPY1 THE PAST FEW YEARS have seen rising interest in foreign fighting as a general phenomenon and in fighters joining jihadist groups in particular. Tunisians figure disproportionately among the foreign jihadist cohort, yet their ubiquity is somewhat confounding. Why Tunisians? This study aims to bring clarity to this question by examining Tunisia’s foreign fighter networks mobilized to Syria and Iraq since 2011, when insurgencies shook those two countries amid the broader Arab Spring uprisings. ©2018 THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. THE WASHINGTON INSTITUTE FOR NEAR EAST POLICY ■ NO. 30 ■ JANUARY 2017 AARON Y. ZELIN Along with seeking to determine what motivated Evolution of Tunisian Participation these individuals, it endeavors to reconcile estimated in the Iraq Jihad numbers of Tunisians who actually traveled, who were killed in theater, and who returned home. The find- Although the involvement of Tunisians in foreign jihad ings are based on a wide range of sources in multiple campaigns predates the 2003 Iraq war, that conflict languages as well as data sets created by the author inspired a new generation of recruits whose effects since 2011. Another way of framing the discussion will lasted into the aftermath of the Tunisian revolution. center on Tunisians who participated in the jihad fol- These individuals fought in groups such as Abu Musab lowing the 2003 U.S. -

The Special Studies Series Foreign Nations

This item is a finding aid to a ProQuest Research Collection in Microform. To learn more visit: www.proquest.com or call (800) 521-0600 This product is no longer affiliated or otherwise associated with any LexisNexis® company. Please contact ProQuest® with any questions or comments related to this product. About ProQuest: ProQuest connects people with vetted, reliable information. Key to serious research, the company has forged a 70-year reputation as a gateway to the world’s knowledge – from dissertations to governmental and cultural archives to news, in all its forms. Its role is essential to libraries and other organizations whose missions depend on the delivery of complete, trustworthy information. 789 E. Eisenhower Parkway ■ P.O Box 1346 ■ Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 ■ USA ■ Tel: 734.461.4700 ■ Toll-free 800-521-0600 ■ www.proquest.com A Guide to the Microfilm Edition of THE SPECIAL STUDIES SERIES FOREIGN NATIONS The Middle East War in Iraq 2003–2006 A UPA Collection from Cover: Neighborhood children follow U.S. army personnel conducting a patrol in Tikrit, Iraq, on December 27, 2006. Photo courtesy of U.S. Department of Defense Visual Information Center (http://www.dodmedia.osd.mil/). The Special Studies Series Foreign Nations The Middle East War in Iraq 2003–2006 Guide by Jeffrey T. Coster A UPA Collection from 7500 Old Georgetown Road Bethesda, MD 20814-6126 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Middle East war in Iraq, 2003–2006 [microform] / project editors, Christian James and Daniel Lewis. microfilm reels ; 35 mm. – (Special studies series, foreign nations) Summary: Reproduces reports issued by U.S. -

Volume XIII, Issue 21 October 30, 2015

VOLUME XIII, ISSUE 21 u OCTOBER 30, 2015 IN THIS ISSUE: BRIEFS ............................................................................................................................1 THE SWARM: TERRORIST INCIDENTS IN FRANCE By Timothy Holman .........................................................................................................3 CAUGHT BETWEEN RUSSIA, THE UNITED STATES AND TURKEY, Cars continue to burn SYRIAN KURDS FACE DILEMMA after a suicide attack By Wladimir van Wilgenburg .........................................................................................5 by the Islamic State in Beirut. THE EVOLUTION OF SUNNI JIHADISM IN LEBANON SINCE 2011 By Patrick Hoover .............................................................................................................8 Terrorism Monitor is a publication of The Jamestown Foundation. BANGLADESH ATTACKS SHOW INCREASING ISLAMIC STATE The Terrorism Monitor is INFLUENCE designed to be read by policy- makers and other specialists James Brandon yet be accessible to the general public. The opinions expressed within are solely those of the In the last six weeks, Bangladesh has been hit by a near-unprecedented series of Islamist authors and do not necessarily militant attacks targeting foreigners and local Shi’a Muslims. On September 28, an reflect those of The Jamestown Italian NGO worker, who was residing in the country, was shot and killed by attackers Foundation. on a moped as he was jogging near the diplomatic area of capital city Dhaka (Daily Star [Dhaka], September -

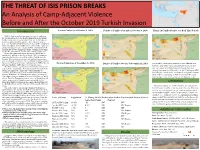

Methodology Results Introducfion Addifional Informafion Limitafions

THE THREAT OF ISIS PRISON BREAKS An Analysis of Camp-Adjacent Violence Before and After the October 2019 Turkish Invasion Faction Control (as of October 9, 2019) Density of Conflict (September 2-October 8, 2019) Change in Conflict Density over Both Time Periods Introduction With the Syrian conflict soon posed to enter its ninth year, the war has proven to be the greatest humanitarian and interna- tional security crisis in a generation. However, in the last year — at least in north-east of the country—there had been relative peace. The Kurdish Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), along with American support, had consolidated its control of the region and all but rooted out the last remnants of ISIS. As of this fall, U.S. and SDF forces were engaged in counter-terrorism raids, ensur- ing that the now-stateless Islamic State remained suppressed. On the other side of the Syrian border sits Turkey, which considers the SDF to be directly tied to the PKK, a terrorist or- ganization that has been in conflict with the Turkish state for decades. This, combined with domestic political pressure to re- settle the millions of Syrian refugees currently residing within its borders, led Turkey to formulate a plan to invade SDF-held terri- Faction Control (as of November 16, 2019) Density of Conflict (October 9-November 16, 2019) records) while investigating potential escapes. Although over tory and establish a “buffer zone” in the border region. half of the total camps changed faction hands during the inva- The United States, eager to protect its wartime partners and to prevent the destabilizing effects of a Turkish incursion in the sion, none ended up in Turkish control. -

Summary of Information on Jihadist Websites the First Half of August 2015

ICT Jihadi Monitoring Group PERIODIC REVIEW Bimonthly Report Summary of Information on Jihadist Websites The First Half of August 2015 International Institute for Counter Terrorism (ICT) Additional resources are available on the ICT Website: www.ict.org.il This report summarizes notable events discussed on jihadist Web forums during the first half of August 2015. Following are the main points covered in the report: Following a one-year absence, Sheikh Ayman al-Zawahiri re-emerges in the media in order to give a eulogy in memory of Mullah Omar, the leader of the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, and to swear allegiance to its new leader, Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansoor. Al-Zawahiri vows to work to apply shari’a and continue to wage jihad until the release of all Muslim occupied lands. In addition, he emphasized that the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan is the only legitimate emirate. The next day, Mullah Akhtar Mohammad Mansoor announces that he accepted al- Zawahiri’s oath of allegiance. In addition, various Al-Qaeda branches and jihadist organizations that support Al-Qaeda gave eulogies in memory of Mullah Omar. Hamza bin Laden, the son of former Al-Qaeda leader, Osama bin Laden, renews his oath of allegiance to the leader of the Taliban in Afghanistan, Ayman al-Zawahiri, and praises the leaders of Al-Qaeda branches for fulfilling the commandment to wage jihad against the enemies of Islam. In reference to the arena of jihad in Syria, he recommends avoiding internal struggles among the mujahideen in Syria and he calls for the liberation of Al-Aqsa Mosque from the Jews. -

UN Assistance Mission for Iraq ﺑﻌﺜﺔ اﻷﻣﻢ اﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪة (UNAMI) ﻟﺘﻘﺪﻳﻢ اﻟﻤﺴﺎﻋﺪة

ﺑﻌﺜﺔ اﻷﻣﻢ اﻟﻤﺘﺤﺪة UN Assistance Mission for Iraq ﻟﺘﻘﺪﻳﻢ اﻟﻤﺴﺎﻋﺪة ﻟﻠﻌﺮاق (UNAMI) Human Rights Report 1 September– 31 October 2006 Summary 1. Despite the Government’s strong commitment to address growing human rights violations and lay the ground for institutional reform, violence reached alarming levels in many parts of the country affecting, particularly, the right to life and personal integrity. 2. The Iraqi Government, MNF-I and the international community must increase efforts to reassert the authority of the State and ensure respect for the rule of law by dismantling the growing influence of armed militias, by combating corruption and organized crime and by maintaining discipline within the security and armed forces. In this respect, it is encouraging that the Government, especially the Ministry of Human Rights, is engaged in the development of a national system based on the respect of human rights and the rule of law and is ready to address issues related to transitional justice so as to achieve national reconciliation and dialogue. 3. The preparation of the International Compact for Iraq, an agreement between the Government and the international community to achieve peace, stability and development based on the rule of law and respect for human rights, is perhaps a most significant development in the period. The objective of the Compact is to facilitate reconstruction and development while upholding human rights, the rule of law, and overcoming the legacy of the recent and distant past. 4. UNAMI Human Rights Office (HRO) received information about a large number of indiscriminate and targeted killings. Unidentified bodies continued to appear daily in Baghdad and other cities. -

Losing Their Last Refuge: Inside Idlib's Humanitarian Nightmare

Losing Their Last Refuge INSIDE IDLIB’S HUMANITARIAN NIGHTMARE Sahar Atrache FIELD REPORT | SEPTEMBER 2019 Cover Photo: Displaced Syrians are pictured at a camp in Kafr Lusin near the border with Turkey in Idlib province in northwestern Syria. Photo Credit: AAREF WATAD/AFP/Getty Images. Contents 4 Summary and Recommendations 8 Background 9 THE LAST RESORT “Back to the Stone Age:” Living Conditions for Idlib’s IDPs Heightened Vulnerabilities Communal Tensions 17 THE HUMANITARIAN RESPONSE UNDER DURESS Operational Challenges Idlib’s Complex Context Ankara’s Mixed Role 26 Conclusion SUMMARY As President Bashar al-Assad and his allies retook a large swath of Syrian territory over the last few years, rebel-held Idlib province and its surroundings in northwest Syria became the refuge of last resort for nearly 3 million people. Now the Syrian regime, backed by Russia, has launched a brutal offensive to recapture this last opposition stronghold in what could prove to be one of the bloodiest chapters of the Syrian war. This attack had been forestalled in September 2018 by a deal reached in Sochi, Russia between Russia and Turkey. It stipulated the withdrawal of opposition armed groups, including Hay’at Tahrir as-Sham (HTS)—a former al-Qaeda affiliate—from a 12-mile demilitarized zone along the front lines, and the opening of two major HTS-controlled routes—the M4 and M5 highways that cross Idlib—to traffic and trade. In the event, HTS refused to withdraw and instead reasserted its dominance over much of the northwest. By late April 2019, the Sochi deal had collapsed in the face of the Syrian regime’s military escalation, supported by Russia.