God Wears Tom Ford: Hip Hop's Revisioning of Divine Authority

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Top Ten Fashion Designers

Top Ten Fashion Designers In a society where we are bombarded with fashion, how on earth do we decide who the top ten designers are? Well, after quite a lot of pondering, I came up with some names that I thought were a well-rounded group of creative minds. These are the best from all over the board. So here goes. 1. VALENTINO GARAVANI. From Italy, this man knows how to make a woman look like a goddess. Having dressed many of the world's most famous leading ladies (such as Julia Roberts and Elizabeth Taylor), he has proven his talent and risen to the top as The King of Elegance. 2. TOM FORD Born in Texas this man is not only the Creative Director for Gucci, he's also the Creative Director for Yves Saint Laurent. Ford won the Best International Designer Award in 2000. 3. DONATELLA VERSACE is one of fashions most loved divas. Born in Calabria Italy, she took over her late brother Gianni Versace's design house. By following in his footsteps Donatella has become known for her sexy yet elegant designs. 4. ALEXANDER MCQUEEN is one of the worlds most innovative and outstanding designers. Known for his theatrical influence, his creations are not only beautiful but also colourful and raw. 5. BETSEY JOHNSON. Her designs are brilliant, bold and fun. They are funky and edgy, with a lifetime of flare. Straight from the American fashion capital [New York] Betsey is known for "her celebration of the exuberant". 6. RALPH LAUREN. He could possibly be the king of ready-to wear. -

And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron J

Claremont Colleges Scholarship @ Claremont Pomona Senior Theses Pomona Student Scholarship 2015 And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron J. Cook Pomona College Recommended Citation Cook, Cameron J., "And I Heard 'Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic" (2015). Pomona Senior Theses. Paper 138. http://scholarship.claremont.edu/pomona_theses/138 This Open Access Senior Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Pomona Student Scholarship at Scholarship @ Claremont. It has been accepted for inclusion in Pomona Senior Theses by an authorized administrator of Scholarship @ Claremont. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 And I Heard ‘Em Say: Listening to the Black Prophetic Cameron Cook Senior Thesis Class of 2015 Bachelor of Arts A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the Bachelor of Arts degree in Religious Studies Pomona College Spring 2015 2 Table of Contents Acknowledgements Chapter One: Introduction, Can You Hear It? Chapter Two: Nina Simone and the Prophetic Blues Chapter Three: Post-Racial Prophet: Kanye West and the Signs of Liberation Chapter Four: Conclusion, Are You Listening? Bibliography 3 Acknowledgments “In those days it was either live with music or die with noise, and we chose rather desperately to live.” Ralph Ellison, Shadow and Act There are too many people I’d like to thank and acknowledge in this section. I suppose I’ll jump right in. Thank you, Professor Darryl Smith, for being my Religious Studies guide and mentor during my time at Pomona. Your influence in my life is failed by words. Thank you, Professor John Seery, for never rebuking my theories, weird as they may be. -

Sonic Necessity-Exarchos

Sonic Necessity and Compositional Invention in #BluesHop: Composing the Blues for Sample-Based Hip Hop Abstract Rap, the musical element of Hip-Hop culture, has depended upon the recorded past to shape its birth, present and, potentially, its future. Founded upon a sample-based methodology, the style’s perceived authenticity and sonic impact are largely attributed to the use of phonographic records, and the unique conditions offered by composition within a sampling context. Yet, while the dependence on pre-existing recordings challenges traditional notions of authorship, it also results in unavoidable legal and financial implications for sampling composers who, increasingly, seek alternative ways to infuse the sample-based method with authentic content. But what are the challenges inherent in attempting to compose new material—inspired by traditional forms—while adhering to Rap’s unique sonic rationale, aesthetics and methodology? How does composing within a stylistic frame rooted in the past (i.e. the Blues) differ under the pursuit of contemporary sonics and methodological preferences (i.e. Hip-Hop’s sample-based process)? And what are the dynamics of this inter-stylistic synthesis? The article argues that in pursuing specific, stylistically determined sonic objectives, sample-based production facilitates an interactive typology of unique conditions for the composition, appropriation, and divergence of traditional musical forms, incubating era-defying genres that leverage the dynamics of this interaction. The musicological inquiry utilizes (auto)ethnography reflecting on professional creative practice, in order to investigate compositional problematics specific to the applied Blues-Hop context, theorize on the nature of inter- stylistic composition, and consider the effects of electronic mediation on genre transformation and stylistic morphing. -

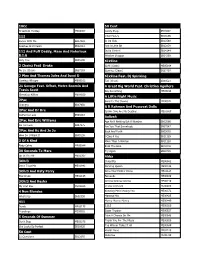

Karaoke Song List

10Cc 50 Cent Dreadlock Holiday MX00002 Candy Shop SB13602 112 I Got Money SB16596 Dance With Me SB17659 In Da Club SB12588 Peaches And Cream SB12012 Just A Little Bit SB13839 112 And Puff Daddy, Mase And Notorious Outta Control SB14144 B.I.G Window Shopper SB14269 Only You SB05190 6Ix9ine 2 Chainz Feat Drake Gotti (Clean) ME05164 No Lie (Clean) SB27103 Gummo (Clean) SB32797 2 Play And Thomas Jules And Jucxi D 6Ix9ine Feat. Dj Spinking Careless Whisper ME00102 Tati (Clean) SB33521 21 Savage Feat. Offset, Metro Boomin And A Great Big World Feat. Christina Aguilera Travis Scott Say Something ME03194 Ghostface Killers ME04019 A Little Night Music 2Pac Send In The Clowns ME00572 Changes SB07950 A R Rahman And Pussycat Dolls 2Pac And Dr Dre Jai Ho (You Are My Destiny) ME01867 California Love SB04883 Aaliyah 2Pac And Eric Williams Age Ain't Nothing But A Number SB03566 Do For Love SB07275 Are You That Somebody SB07547 2Pac And Kc And Jo Jo Back And Forth SB03062 How Do U Want It SB05238 I Care 4 You SB11129 3 Of A Kind More Than A Woman SB11128 Baby Cakes ME00044 Rock The Boat SB12016 30 Seconds To Mars Try Again SB09709 Up In The Air ME02907 Abba 3Oh!3 Chiquitita ME00982 Don't Trust Me ME01942 Dancing Queen ME00146 3Oh!3 And Katy Perry Does Your Mother Know ME01124 Starstrukk ME02145 Fernando ME00989 3Oh!3 And Kesha Gimme Gimme Gimme ME00219 My First Kiss ME02263 I Have A Dream ME00288 4 Non Blondes Knowing Me Knowing You ME00372 What's Up SB02550 Mamma Mia ME00425 411 Money Money Money ME00449 Dumb ME00175 S.O.S ME00560 Teardrops ME00651 Super -

Fashion Awards Preview

WWD A SUPPLEMENT TO WOMEN’S WEAR DAILY 2011 CFDA FASHION AWARDS PREVIEW 053111.CFDA.001.Cover.a;4.indd 1 5/23/11 12:47 PM marc jacobs stores worldwide helena bonham carter www.marcjacobs.com photographed by juergen teller marc jacobs stores worldwide helena bonham carter www.marcjacobs.com photographed by juergen teller NEW YORK LOS ANGELES BOSTON LAS VEGAS MIAMI DALLAS SAO PAULO LONDON PARIS SAINT TROPEZ BRUSSELS ANTWERPEN KNOKKE MADRID ATHENS ISTANBUL MOSCOW DUBAI HONG KONG BEIJING SHANGHAI MACAU JAKARTA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE SEOUL TOKYO SYDNEY DVF.COM NEW YORK LOS ANGELES BOSTON LAS VEGAS MIAMI DALLAS SAO PAULO LONDON PARIS SAINT TROPEZ BRUSSELS ANTWERPEN KNOKKE MADRID ATHENS ISTANBUL MOSCOW DUBAI HONG KONG BEIJING SHANGHAI MACAU JAKARTA KUALA LUMPUR SINGAPORE SEOUL TOKYO SYDNEY DVF.COM IN CELEBRATION OF THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF SWAROVSKI’S SUPPORT OF THE CFDA FASHION AWARDS AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH SWAROVSKI BOUTIQUES NEW YORK # LOS ANGELES COSTA MESA # CHICAGO # MIAMI # 1 800 426 3088 # WWW.ATELIERSWAROVSKI.COM BRAIDED BRACELET PHOTOGRAPHED BY MITCHELL FEINBERG IN CELEBRATION OF THE 10TH ANNIVERSARY OF SWAROVSKI’S SUPPORT OF THE CFDA FASHION AWARDS AVAILABLE EXCLUSIVELY THROUGH SWAROVSKI BOUTIQUES NEW YORK # LOS ANGELES COSTA MESA # CHICAGO # MIAMI # 1 800 426 3088 # WWW.ATELIERSWAROVSKI.COM BRAIDED BRACELET PHOTOGRAPHED BY MITCHELL FEINBERG WWD Published by Fairchild Fashion Group, a division of Advance Magazine Publishers Inc., 750 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017 EDITOR IN CHIEF ADVERTISING Edward Nardoza ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER, Melissa Mattiace ADVERTISING DIRECTOR, Pamela Firestone EXECUTIVE EDITOR, BEAUTY Pete Born PUBLISHER, BEAUTY INC, Alison Adler Matz EXECUTIVE EDITOR Bridget Foley SALES DEVELOPMENT DIRECTOR, Jennifer Marder EDITOR James Fallon ASSOCIATE PUBLISHER, INNERWEAR/LEGWEAR/TEXTILE, Joel Fertel MANAGING EDITOR Peter Sadera EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, INTERNATIONAL FASHION, Matt Rice MANAGING EDITOR, FASHION/SPECIAL REPORTS Dianne M. -

Trap Pilates POPUP

TRAP PILATES …Everything is Love "The Carters" June 2018 POP UP… Shhh I Do Trap Pilates DeJa- Vu INTR0 Beyonce & JayZ SUMMER Roll Ups….( Pelvic Curl | HipLifts) (Shoulder Bridge | Leg Lifts) The Carters APESHIT On Back..arms above head...lift up lifting right leg up lower slowly then lift left leg..alternating SLOWLY The Carters Into (ROWING) Fingers laced together going Side to Side then arms to ceiling REPEAT BOSS Scissors into Circles The Carters 713 Starting w/ Plank on hands…knee taps then lift booty & then Inhale all the way forward to your tippy toes The Carters exhale booty toward the ceiling….then keep booty up…TWERK shake booty Drunk in Love Lit & Wasted Beyonce & Jayz Crazy in Love Hands behind head...Lift Shoulders extend legs out and back into crunches then to the ceiling into Beyonce & JayZ crunches BLACK EFFECT Double Leg lifts The Carters FRIENDS Plank dips The Carters Top Off U Dance Jay Z, Beyonce, Future, DJ Khalid Upgrade You Squats....($$$MOVES) Beyonce & Jay-Z Legs apart feet plie out back straight squat down and up then pulses then lift and hold then lower lift heel one at a time then into frogy jumps keeping legs wide and touch floor with hands and jump back to top NICE DJ Bow into Legs Plie out Heel Raises The Carters 03'Bonnie & Clyde On all 4 toes (Push Up Prep Position) into Shoulder U Dance Beyonce & JayZ Repeat HEARD ABOUT US On Back then bend knees feet into mat...Hip lifts keeping booty off the mat..into doubles The Cartersl then walk feet ..out out in in.. -

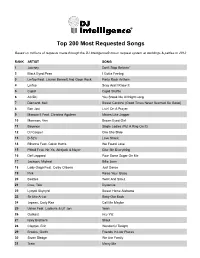

Most Requested Songs of 2012

Top 200 Most Requested Songs Based on millions of requests made through the DJ Intelligence® music request system at weddings & parties in 2012 RANK ARTIST SONG 1 Journey Don't Stop Believin' 2 Black Eyed Peas I Gotta Feeling 3 Lmfao Feat. Lauren Bennett And Goon Rock Party Rock Anthem 4 Lmfao Sexy And I Know It 5 Cupid Cupid Shuffle 6 AC/DC You Shook Me All Night Long 7 Diamond, Neil Sweet Caroline (Good Times Never Seemed So Good) 8 Bon Jovi Livin' On A Prayer 9 Maroon 5 Feat. Christina Aguilera Moves Like Jagger 10 Morrison, Van Brown Eyed Girl 11 Beyonce Single Ladies (Put A Ring On It) 12 DJ Casper Cha Cha Slide 13 B-52's Love Shack 14 Rihanna Feat. Calvin Harris We Found Love 15 Pitbull Feat. Ne-Yo, Afrojack & Nayer Give Me Everything 16 Def Leppard Pour Some Sugar On Me 17 Jackson, Michael Billie Jean 18 Lady Gaga Feat. Colby O'donis Just Dance 19 Pink Raise Your Glass 20 Beatles Twist And Shout 21 Cruz, Taio Dynamite 22 Lynyrd Skynyrd Sweet Home Alabama 23 Sir Mix-A-Lot Baby Got Back 24 Jepsen, Carly Rae Call Me Maybe 25 Usher Feat. Ludacris & Lil' Jon Yeah 26 Outkast Hey Ya! 27 Isley Brothers Shout 28 Clapton, Eric Wonderful Tonight 29 Brooks, Garth Friends In Low Places 30 Sister Sledge We Are Family 31 Train Marry Me 32 Kool & The Gang Celebration 33 Sinatra, Frank The Way You Look Tonight 34 Temptations My Girl 35 ABBA Dancing Queen 36 Loggins, Kenny Footloose 37 Flo Rida Good Feeling 38 Perry, Katy Firework 39 Houston, Whitney I Wanna Dance With Somebody (Who Loves Me) 40 Jackson, Michael Thriller 41 James, Etta At Last 42 Timberlake, Justin Sexyback 43 Lopez, Jennifer Feat. -

(2001) 96- 126 Gangsta Misogyny: a Content Analysis of the Portrayals of Violence Against Women in Rap Music, 1987-1993*

Copyright © 2001 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture All rights reserved. ISSN 1070-8286 Journal of Criminal Justice and Popular Culture, 8(2) (2001) 96- 126 GANGSTA MISOGYNY: A CONTENT ANALYSIS OF THE PORTRAYALS OF VIOLENCE AGAINST WOMEN IN RAP MUSIC, 1987-1993* by Edward G. Armstrong Murray State University ABSTRACT Gangsta rap music is often identified with violent and misogynist lyric portrayals. This article presents the results of a content analysis of gangsta rap music's violent and misogynist lyrics. The gangsta rap music domain is specified and the work of thirteen artists as presented in 490 songs is examined. A main finding is that 22% of gangsta rap music songs contain violent and misogynist lyrics. A deconstructive interpretation suggests that gangsta rap music is necessarily understood within a context of patriarchal hegemony. INTRODUCTION Theresa Martinez (1997) argues that rap music is a form of oppositional culture that offers a message of resistance, empowerment, and social critique. But this cogent and lyrical exposition intentionally avoids analysis of explicitly misogynist and sexist lyrics. The present study begins where Martinez leaves off: a content analysis of gangsta rap's lyrics and a classification of its violent and misogynist messages. First, the gangsta rap music domain is specified. Next, the prevalence and seriousness of overt episodes of violent and misogynist lyrics are documented. This involves the identification of attributes and the construction of meaning through the use of crime categories. Finally, a deconstructive interpretation is offered in which gangsta rap music's violent and misogynist lyrics are explicated in terms of the symbolic encoding of gender relationships. -

Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Summer 8-2020 Hip-Hop's Diversity and Misperceptions Andrew Cashman Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Music Commons, and the Social and Cultural Anthropology Commons This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HIP-HOP’S DIVERSITY AND MISPERCEPTIONS by Andrew Cashman A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Anthropology) The Honors College University of Maine August 2020 Advisory Committee: Joline Blais, Associate Professor of New Media, Advisor Kreg Ettenger, Associate Professor of Anthropology Christine Beitl, Associate Professor of Anthropology Sharon Tisher, Lecturer, School of Economics and Honors Stuart Marrs, Professor of Music 2020 Andrew Cashman All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT The misperception that hip-hop is a single entity that glorifies wealth and the selling of drugs, and promotes misogynistic attitudes towards women, as well as advocating gang violence is one that supports a mainstream perspective towards the marginalized.1 The prevalence of drug dealing and drug use is not a picture of inherent actions of members in the hip-hop community, but a reflection of economic opportunities that those in poverty see as a means towards living well. Some artists may glorify that, but other artists either decry it or offer it as a tragic reality. In hip-hop trends build off of music and music builds off of trends in a cyclical manner. -

UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS of LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS in HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 By

ON THE BEAT: UNDERSTANDING PORTRAYALS OF LAW ENFORCEMENT OFFICERS IN HIP-HOP LYRICS SINCE 2009 by Francesca A. Keesee A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of George Mason University in Partial Fulfillment of The Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Science Conflict Analysis and Resolution Master of Arts Conflict Resolution and Mediterranean Security Committee: ___________________________________________ Chair of Committee ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ ___________________________________________ Graduate Program Director ___________________________________________ Dean, School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Date: _____________________________________ Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, VA University of Malta Valletta, Malta On the Beat: Understanding Portrayals of Law Enforcement Officers in Hip-hop Lyrics Since 2009 A Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degrees of Master of Science at George Mason University and Master of Arts at the University of Malta by Francesca A. Keesee Bachelor of Arts University of Virginia, 2015 Director: Juliette Shedd, Professor School for Conflict Analysis and Resolution Fall Semester 2017 George Mason University Fairfax, Virginia University of Malta Valletta, Malta Copyright 2016 Francesca A. Keesee All Rights Reserved ii DEDICATION This is dedicated to all victims of police brutality. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am forever grateful to my best friend, partner in crime, and husband, Patrick. -

Bradley Syllabus for South

Special Topics in African American Literature: OutKast and the Rise of the Hip Hop South Regina N. Bradley, Ph.D. Course Description In 1995, Atlanta, GA, duo OutKast attended the Source Hip Hop Awards, where they won the award for best new duo. Mostly attended by bicoastal rappers and hip hop enthusiasts, OutKast was booed off the stage. OutKast member Andre Benjamin, clearly frustrated, emphatically declared what is now known as the rallying cry for young black southerners: “the South got something to say.” For this course, we will use OutKast’s body of work as a case study questioning how we recognize race and identity in the American South after the civil rights movement. Using a variety of post–civil rights era texts including film, fiction, criticism, and music, students will interrogate OutKast’s music as the foundation of what the instructor theorizes as “the hip hop South,” the southern black social-cultural landscape in place over the last twenty-five years. Course Objectives 1. To develop and utilize a multidisciplinary critical framework to successfully engage with conversations revolving around contemporary identity politics and (southern) popular culture 2. To challenge students to engage with unfamiliar texts, cultural expressions, and language in order to learn how to be socially and culturally sensitive and aware of modes of expression outside of their own experiences. 3. To develop research and writing skills to create and/or improve one’s scholarly voice and others via the following assignments: • Critical listening journal • Nerdy hip hop review **Explicit Content Statement** (courtesy: Dr. Treva B. Lindsey) Over the course of the semester students will be introduced to texts that may be explicit in nature (i.e., cursing, sexual content). -

No Church in the Wild

No Church in the wild Who was rubbin' the wood like Kiki Shepard Two tattoos, one read "no apologies" Human beings in a mob The other said "love is cursed by monogamy" What's a mob to a king? That's somethin' that the pastor don't preach What's a king to a god? That's somethin' that a teacher can't teach What's a god to a non-believer? When we die, the money we can't keep Who don't believe in anything? But we prolly spend it all 'cause the pain ain't cheap, preach We make it out alive All right, all right Human beings in a mob No church in the wild What's a mob to a king? What's a king to a god? Tears on the mausoleum floor What's a god to a non-believer? Blood stains the Coliseum doors Who don't believe in anything? Lies on the lips of a priest Thanksgiving disguised as a feast We make it out alive Rollin' in the Rolls-Royce Corniche All right, all right Only the doctors got this, I'm hidin' from police No church in the wild Cocaine seats No church in the wild All white like I got the whole thing bleached No church in the wild Drug dealer chic No church in the wild I'm wonderin' if a thug's prayers reach Is Pious pious 'cause God loves pious? Socrates asks, "whose bias do y'all seek?" All for Plato, screech I'm out chere' ballin', I know y'all hear my sneaks Jesus was a carpenter, Yeezy, laid beats Hova flow the Holy Ghost, get the hell up out your seats, preach Human beings in a mob What's a mob to a king? What's a king to a god? What's a god to a non-believer? Who don't believe in anything? We make it out alive All right, all right No church in the wild I live by you, desire I stand by you, walk through the fire Your love, is my scripture Let me into your encryption, yeah yeah Coke on her black skin made a stripe like a zebra I call that jungle fever You will not control the threesome Just roll the weed up until I get me some We formed a new religion No sins as long as there's permission' And deception is the only felony So never fuck nobody without tellin' me Sunglasses and Advil Last night was mad real Sun comin' up 5 a.m.