Sugar Creek Gang Series

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

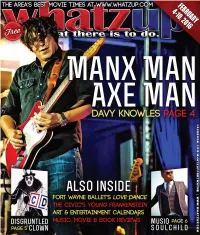

Musiq Soulchild

FEBRUARY 4-10, 2016 FACEBOOK.COM/WHATZUPFORTWAYNE | WWW.WHATZUP.COM BUY ONE LUNCH O R DINNER , GET O NE Buy 2 Entrees fo R 1/2 Off & Get Free (Of Equal or Lesser Value; whatzup Dining Club Appetizer Excludes Appetizers) (up to $10) NOT A COUPON 4001 S. WAyNE STREET 135 W. Columbia St. • Fort Wayne FT. WAyNE~260.745.3369 260-422-7500 • NOT A COUPON Buy One BUY ONE Entree ENTREE Save Big ET NE G O Get One FREE Free (of equal or lesser value; up to $8) NOT NOT A COUPON (up to $8) MAD ANTHONY BREWING COMPANY 1915 S. Calhoun St., Fort Wayne 2002 S. Broadway • Fort Wayne 260-456-7005 at 20 Fine 260-426-2537 • NOT A COUPON NOT A BUY ONE 10% OFF COUPON Not Valid on Alcohol SANDWICH GET Monday-Friday Dine-In Only ONE FREE w/One Drink Minimum Restaurants Mon.-Thurs. Only 4205 Bluffton Rd. The whatzup Dining Club Card entitles you to Buy One - Get One Free (or similar) NOT A COUPON Fort Wayne Burgers • Bands • Bourbon savings at the 20 fine Fort Wayne area restaurants on this page. 4910 N. Clinton, Ft. Wayne, 209.2117 260-747-9964 At just $18.00, your whatzup Dining Club Card will more than pay for itself with just NOT A O’REILLY’S COUPON COUPON NOT NOT A IRISH BAR & one or two uses. To save even more, get additional cards for yourself or for family and RESTAURANT friends for just $15 apiece, a 16% discount. FREE APPETIZER Here’s How the whatzup Dining Club Card Works: w/PURCHASE OF Buy One Entree • Get One 1/2 Off 2 ENTREES (Up to $10) 1. -

Extensions of Remarks 10509

May 9, 1979 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS 10509 MENT REPORT.-The Secretary shall set forth available to the United States Geological -Page 274, line 1, strike "(b) (1)" and in in each report to the Congress under the Survey, the Bureau of Mines, or any other lieu thereof insert "(c) (2)". Mining and Minerals Policy Act of 1970 a agency or instrumentality of the United Page 333, lines 14 and 15, strike "after the summary of the pertinent information States. date of enactment of this Act". (other than proprietary or other confidential (Additional technical amendments to -Page 275, line 8, change "28" to "27" and information) relating to minerals which is Udall-Anderson substitute (H.R. 3651) .) change "33" to "34". EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS A NONFUEL MINERAL POLICY: WE Of course, the usual antagonists are lined These Americans descend from .Japa CAN NO LONGER WAIT up on each side of this policy debate. But, nese, Chinese, Korean, and Filipino an as Nevada Congressman J. D. Santini points cestors, as well as from Hawaii and t'iher out in our p . 57 feature, their arguments Pacific Islands such as Samoa, Fiji, and HON. JIM SANTINI go by one another like ships in the night with nothing happening-until the lid blows Tahiti. In southern California, where OF NEVADA off. we have the greatest concentration of IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES But, how do you get the public excited Asian and Pacific Americans anywhere Wednesday, May 9, 1979 about metal shortages? in the Nation, their valuable involvemept Even Congressman Santini's well-meant in the growth and prosperity of our local • Mr. -

An Analysis of Hegemonic Social Structures in "Friends"

"I'LL BE THERE FOR YOU" IF YOU ARE JUST LIKE ME: AN ANALYSIS OF HEGEMONIC SOCIAL STRUCTURES IN "FRIENDS" Lisa Marie Marshall A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY August 2007 Committee: Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor Audrey E. Ellenwood Graduate Faculty Representative James C. Foust Lynda Dee Dixon © 2007 Lisa Marshall All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Katherine A. Bradshaw, Advisor The purpose of this dissertation is to analyze the dominant ideologies and hegemonic social constructs the television series Friends communicates in regard to friendship practices, gender roles, racial representations, and social class in order to suggest relationships between the series and social patterns in the broader culture. This dissertation describes the importance of studying television content and its relationship to media culture and social influence. The analysis included a quantitative content analysis of friendship maintenance, and a qualitative textual analysis of alternative families, gender, race, and class representations. The analysis found the characters displayed actions of selectivity, only accepting a small group of friends in their social circle based on friendship, gender, race, and social class distinctions as the six characters formed a culture that no one else was allowed to enter. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This project stems from countless years of watching and appreciating television. When I was in college, a good friend told me about a series that featured six young people who discussed their lives over countless cups of coffee. Even though the series was in its seventh year at the time, I did not start to watch the show until that season. -

The Cine-Kodak News; Vol. 8, No. 10; Sept

SEPTEMBER OCTOBER 1932 _ S_P_f_f _D_ makes it the film for autumn use p ERHAPS your movie "stars" spend most of their daytime hours in school ... are available for picture making only in late afternoon or evening. So load your camera with Cine-Kodak Super-sensitive Film ... it doubles the outdoor effect iveness of your camera's lens . and go on making pictures regardless of the diminished autumn sunshine. For this remarkable fi lm has all the speed you ' II need to get the shots you want. Twice as fast as regular Panchromatic Film in daylight ... at least three times as fast under artificial Cine~Kodak Super-sensitive Pan- light. chromatic Film- costs only .$4 the 50-foot roll. Makes even indoor Cine~Kodak Super~sensitive " Pan" puts your camera on a movies easy to take with 35 cent year round, day or night basis of reliable movie making. Photoflood lamps. Cine-Kodak Super-sensitive Panchromatic Film SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 1932 Published Bi-Monthly in th e interests of Amateur Motion Pictures by the E WS Eastman Kodak Company, Rochester, N . Y., Volume 8, Numbe r 10. TRANSOCEANIC by Henry Locksmith FIFTY years ago, when one left his homeland to go to America, We bought a Cine-Kodak, several hundred fee t of film, and it was a definite turning point. started. Friendly faces and places, the things with which one had The house, outside and inside .. the grounds ... the baby grown up, were lost- cut off completely. Perhaps an occasional ... ourselves .. a party . .. our neighbors and friends ... the visit- spaced years apart- but much that one had known was pets .. -

Season 5 Article

N.B. IT IS RECOMMENDED THAT THE READER USE 2-PAGE VIEW (BOOK FORMAT WITH SCROLLING ENABLED) IN ACROBAT READER OR BROWSER. “EVEN’ING IT OUT – A NEW PERSPECTIVE ON THE LAST TWO YEARS OF “THE TWILIGHT ZONE” Television Series (minus ‘THE’)” A Study in Three Parts by Andrew Ramage © 2019, The Twilight Zone Museum. All rights reserved. Preface With some hesitation at CBS, Cayuga Productions continued Twilight Zone for what would be its last season, with a thirty-six episode pipeline – a larger count than had been seen since its first year. Producer Bert Granet, who began producing in the previous season, was soon replaced by William Froug as he moved on to other projects. The fifth season has always been considered the weakest and, as one reviewer stated, “undisputably the worst.” Harsh criticism. The lopsidedness of Seasons 4 and 5 – with a smattering of episodes that egregiously deviated from the TZ mold, made for a series much-changed from the one everyone had come to know. A possible reason for this was an abundance of rather disdainful or at least less-likeable characters. Most were simply too hard to warm up to, or at the very least, identify with. But it wasn’t just TZ that was changing. Television was no longer as new a medium. “It was a period of great ferment,” said George Clayton Johnson. By 1963, the idyllic world of the 1950s was disappearing by the day. More grittily realistic and reality-based TV shows were imminent, as per the viewing audience’s demand and it was only a matter of time before the curtain came down on the kinds of shows everyone grew to love in the 50s. -

The Lady Onstage by Erin Bregman

The Lady Onstage by Erin Bregman Resource Guide for Teachers Created by: Lauren Bloom Hanover, Director of Education Jeff Denight, Dramaturgy Intern 1 Table of Contents About Profile Theatre 3 How to Use This Resource Guide 4 The Artists 5 Lesson 1: Historical Context 6 Classroom Activities: 1) Biography and Context 6 2) Knipper and Chekov in Their Own Words 6 3) The Development of The Lady Onstage 8 4) Considering Contemporary Cultural Shifts (Homework) 9 Supplemental Materials 10 Lesson 2: The Process of Play Development 21 Classroom Activities 1) Where Do New Plays Come From? 21 2) Exploring a Play We Know 23 3) How to Start - the Development Process in Action 24 4) Starting Your Own Play (Homework) 24 Supplemental Materials 26 Lesson 3: One Person Plays - A Unique Challenge 34 Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Single-Character Monologues 34 2) Exploring Multi-character Solo Performances 35 3) Writing Your Own Monologue (Homework) 36 Supplemental Materials 38 Lesson 4: Chekhov Today: Translations and Adaptations 41 Classroom Activities 1) Exploring Translations 42 2) Exploring Work Inspired by Chekhov 42 3) Creating Your Own Adaptation 43 Supplemental Materials 44 Lesson 5: Reflecting on the Performance Classroom Activities 1) Classroom Discussion and Reflection 52 2) What We’ve Learned 52 3) Creative Writing (Homework) 53 2 About Profile Theatre Profile Theatre was founded in 1997 with the mission of celebrating the playwright’s contribution to live theater. Each year Profile produces a season of plays devoted to a single playwright, engaging with our community to explore that writer’s vision and influence on theatre and the world at large. -

Here I Come with All My Black Girl Magic”: Black Women and Girls’ Experiences in Predominantly White Independent Private Schools

“HERE I COME WITH ALL MY BLACK GIRL MAGIC”: BLACK WOMEN AND GIRLS’ EXPERIENCES IN PREDOMINANTLY WHITE INDEPENDENT PRIVATE SCHOOLS BY DEVEAN R. OWENS DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Education Policy, Organization and Leadership with a concentration in Diversity and Equity in Education in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2020 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Associate Professor Anjalé Welton, Chair Professor Ruth Nicole Brown Professor Adrienne Dixson Professor Helen Neville Abstract Within independent private schools specifically, Black women and girls endure feelings of rejection, isolation, and inadequacy all whilst trying to maintain their academic or career success and a positive self-perception. Through the lenses of Black Feminist Thought and Critical Race Theory, this dissertation presents Black women and girls’ true experiences in PWIS which defy dominant deficit beliefs. Participants detailed the racism, erasure, and trauma they endured and the detrimental effects these experiences caused in their lives. They also expressed the importance and value of their relationships with one another. These relationships provided them with the affirmation and confidence they needed to believe in and stand up for themselves. Black women and girls engage in various resistance strategies through living authentically, challenging dominant norms, and advocating for themselves and others in the school community. ii Acknowledgements Students & participants… Thank you for inspiring me! Thank you for taking the time to participate in this study. Drs. Welton, Brown, Dixson, Neville, and Zamani-Gallaher… Thank you for challenging me to think more critically and seeing me through this journey. -

Karaoke Book

10 YEARS 3 DOORS DOWN 3OH!3 Beautiful Be Like That Follow Me Down (Duet w. Neon Hitch) Wasteland Behind Those Eyes My First Kiss (Solo w. Ke$ha) 10,000 MANIACS Better Life StarStrukk (Solo & Duet w. Katy Perry) Because The Night Citizen Soldier 3RD STRIKE Candy Everybody Wants Dangerous Game No Light These Are Days Duck & Run Redemption Trouble Me Every Time You Go 3RD TYME OUT 100 PROOF AGED IN SOUL Going Down In Flames Raining In LA Somebody's Been Sleeping Here By Me 3T 10CC Here Without You Anything Donna It's Not My Time Tease Me Dreadlock Holiday Kryptonite Why (w. Michael Jackson) I'm Mandy Fly Me Landing In London (w. Bob Seger) 4 NON BLONDES I'm Not In Love Let Me Be Myself What's Up Rubber Bullets Let Me Go What's Up (Acoustative) Things We Do For Love Life Of My Own 4 PM Wall Street Shuffle Live For Today Sukiyaki 110 DEGREES IN THE SHADE Loser 4 RUNNER Is It Really Me Road I'm On Cain's Blood 112 Smack Ripples Come See Me So I Need You That Was Him Cupid Ticket To Heaven 42ND STREET Dance With Me Train 42nd Street 4HIM It's Over Now When I'm Gone Basics Of Life Only You (w. Puff Daddy, Ma$e, Notorious When You're Young B.I.G.) 3 OF HEARTS For Future Generations Peaches & Cream Arizona Rain Measure Of A Man U Already Know Love Is Enough Sacred Hideaway 12 GAUGE 30 SECONDS TO MARS Where There Is Faith Dunkie Butt Closer To The Edge Who You Are 12 STONES Kill 5 SECONDS OF SUMMER Crash Rescue Me Amnesia Far Away 311 Don't Stop Way I Feel All Mixed Up Easier 1910 FRUITGUM CO. -

Hollywoodland Text.Pdf

HOLLYWOODLAND HOLLYWOODLAND an american fairy tale JENNIFER BANASH Impetus Press PO Box 10025 Iowa City, IA 52240 www.impetuspress.com [email protected] Publisher Note: This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, businesses, organizations, places, events, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, events, or locales is entirely coincidental. ISBN 0-9776693-0-0 September 2006 Copyright © 2006 Impetus Press. All rights reserved. for my father I’m going to be in the movies if I have to fuck Bela Lugosi to get there. Actresses are a little like race horses. It’s difficult for us when the race is cancelled. This is an attempt at the ultimate motion picture. ••• 2:00 AM, 82 ° She is in her car when it happens, the black roads around Mulholland winding and twisting, unrolling like the soft dark fabric of a magic carpet. Her eyes blur and she squints them repeatedly, leaning forward to see. The needle on the speedometer flies up past eighty, then ninety, the tendons in her right arm straining, muscles burning as she grips the wheel one-handed. Sierra loves to drive more than anything, the feeling of weightlessness, careening through the air, unstoppable. She was fucking unstoppable. She could feel the kid in the seat next to her getting nervous, moving back and forth in his seat, one hand clutching the belt that cut across his skinny frame. His jeans make a harsh scraping sound. The rasp of denim on leather annoys her, and she closes her eyes. -

1Q12 IPG Cable Nets.Xlsm

Independent Programming means a telecast on a Comcast or Total Hours of Independent Programming NBCUniversal network that was produced by an entity Aired During the First Quarter 2012 unaffiliated with Comcast and/or NBCUniversal. Each independent program or series listed has been classified as new or continuing. 2061:30:00 Continuing Independent Series and Programming means series (HH:MM:SS) and programming that began prior to January 18, 2011 but ends on or after January 18, 2011. New Independent Series and Programming means series and programming renewed or picked up on or after January 18, 2011 or that were not on the network prior to January 18, INDEPENDENT PROGRAMMING Independent Programming Report Chiller First Quarter 2012 Network Program Name Episode Name Initial (I) or New (N) or Primary (P) or Program Description Air Date Start Time* End Time* Length Repeat (R)? Continuing (C)? Multicast (M)? (MM/DD/YYYY) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) (HH:MM:SS) CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 01:00:00 02:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 02:30:00 04:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 08:00:00 09:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: HORROR’S CREEPIEST KIDS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 09:30:00 11:00:00 01:30:00 CHILLER ORIGINAL CHILLER 13: THE DECADE'S SCARIEST MOVIE MOMENTS R C P Reality: Other 01/01/2012 11:00:00 12:30:00 01:30:00 CHILLER -

The Outlaws of the Marsh

The Outlaws of the Marsh Shi Nai'an and Luo Guanzhong The Outlaws of the Marsh Table of Contents The Outlaws of the Marsh..................................................................................................................................1 Shi Nai'an and Luo Guanzhong...............................................................................................................1 Chapter 1 Zhang the Divine Teacher Prays to Dispel a Plague Marshal Hong Releases Demons by Mistake....................................................................................................................................................7 Chapter 2 Arms Instructor Wang Goes Secretly to Yanan Prefecture Nine Dragons Shi Jin Wreaks Havoc in Shi Family Village...................................................................................................15 Chapter 3 Master Shi Leaves Huayin County at Night Major Lu Pummels the Lord of the West.......32 Chapter 4 Sagacious Lu Puts Mount Wutai in an Uproar Squire Zhao Repairs Wenshu Monastery....42 Chapter 5 Drunk, the Little King Raises the Gold−Spangled Bed Curtains Lu the Tattooed Monk Throws Peach Blossom Village into Confusion...................................................................................57 Chapter 6 Nine Dragons Shi Jin Robs in Red Pine Forest Sagacious Lu Burns Down Waguan Monastery.............................................................................................................................................67 Chapter 7 The Tattooed Monk Uproots a Willow