Zimbabwe's Land Reform: Myths and Realities

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2021 Rural Livelihoods Assessment Masvingo Province Report

Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVAC) 2021 Rural Livelihoods Assessment Masvingo Province Report ZimVAC is Coordinated By Food And Nutrition Council (FNC) Housed At SIRDC: 1574 Alpes Rd, Hatcliffe, Harare. Tel: +263 242 862 586/862 025 Website: www.fnc.org.zw Email: [email protected] Twitter: @FNCZimbabwe Instagram: fnc_zim Facebook: @FNCZimbabwe 1 Foreword In its endeavour to ‘promote and ensure adequate food and nutrition security for all people at all times’, the Government of Zimbabwe continues to exhibit its commitment towards reducing food and nutrition insecurity, poverty and improving livelihoods amongst the vulnerable populations in Zimbabwe through operationalization of Commitment 6 of the Food and Nutrition Security Policy (FNSP). Under the coordination of the Food and Nutrition Council, the Zimbabwe Vulnerability Assessment Committee (ZimVAC) undertook the 2021 Rural Livelihoods Assessment, the 21st since its inception. ZimVAC is a technical advisory committee comprised of representatives from Government, Development Partners, UN, NGOs, Technical Agencies and the Academia. Through its assessments, ZimVAC continues to collect, synthesize and disseminate high quality information on the food and nutrition security situation in a timely manner. The 2021 RLA was motivated by the need to provide credible and timely data to inform progress of commitments in the National Development Strategy 1 (NDS 1) and inform planning for targeted interventions to help the vulnerable people in both their short and long-term vulnerability context. Furthermore, as the ‘new normal’ under COVID-19 remains fluid and dynamic, characterized by a high degree of uncertainty, the assessment sought to provide up to date information on how rural food systems and livelihoods have been impacted by the pandemic. -

PLAAS RR46 Smeadzim 1.Pdf

Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences Research Report 46 Space, Markets and Employment in Agricultural Development: Zimbabwe Country Report Chrispen Sukume, Blasio Mavedzenge, Felix Murimbarima and Ian Scoones Published by the Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies, Faculty of Economic and Management Sciences, University of the Western Cape, Private Bag X17, Bellville 7535, Cape Town, South Africa Tel: +27 21 959 3733 Fax: +27 21 959 3732 Email: [email protected] Institute for Poverty, Land and Agrarian Studies Research Report no. 46 June 2015 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without prior permission from the publisher or the authors. Copy Editor: Vaun Cornell Series Editor: Rebecca Pointer Photographs: Pamela Ngwenya Typeset in Frutiger Thanks to the UK’s Department for International Development (DfID) and the Economic and Social Research Council’s (ESRC) Growth Research Programme Contents List of tables ................................................................................................................ ii List of figures .............................................................................................................. iii Acronyms and abbreviations ...................................................................................... v 1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ -

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe ZWE38611 Farmers Bikita/Masvingo MDC/ZANU-PF 3 May 2011

Country Advice Zimbabwe Zimbabwe ZWE38611 Farmers Bikita/Masvingo MDC/ZANU-PF 3 May 2011 1. Is there any country information about attacks on farmers in the in Bikita in the district of Masvingo, in April 2008? Sources indicate that attacks took place on farmers in the Masvingo district during April 2008. These attacks coincided with national elections when tension between government and opposition supporters was extremely high. According to a Times Online report from 8 April he farm invasions began on Saturday in Masvingo province, about 160 miles south of the capital, Harare. Five farmers were forced to flee or were trapped inside their homes by drunken mo 1 The same report stated that two farm owners had been forced from their land for voting for the MDC, and farmers and their staff were beaten and threatened with further violence.2 The MDC claimed on 18 April 2008 that the violence started almost immediately after the elections on March 29, and claimed some of its supporters in remote rural areas were homeless after their homes were looted and burnt down by the suspected ZANU PF (Zimbabwe African National Union-Patriotic Front) activists.3 The US Ambassador to Zimbabwe James McGee on 18 April commented on the violence taking place through Zimbabwe: There is growing evidence that rural communities are being punished for their support for opposition candidates. We have disturbing and confirmed reports of threats, beatings, abductions, burning of homes and even murder, from many parts of the country.4 These activities formed part of Operation Mavhoterapapi (who/where did you vote), a campaign designed to intimidate MDC supporters, and centred on rural areas of Zimbabwe. -

The Political Economy of Livelihoods in Contemporary Zimbabwe Edited

The Political Economy of Livelihoods in Contemporary Zimbabwe Edited by Kirk Helliker, Manase Kudzai Chiweshe and Sandra Bhatasara Ö Routledge jjj Taylor &Francis Croup LONDON AND NEW YORK Contents List of illustrations Preface Notes ort contributors 1 Introduction: theorising the political economy of livelihoods in contemporary Zimbabwe SANDRA BHATASARA, MANASE KUDZAI CHIWESHE AND KIRK HELLIKER 2 Livelihood strategies of urban women: einerging evidence from Magaba, Harare TAKUNDA CHIRAU 3 Livelihood strategies in Harare: the case of low-income households in Budiriro TAFADZWA CHEVO 4 Sex work as a livelihood strategy in the border town of Beitbridge WADZANAI TAKAWIRA AND KIRK HELLIKER 5 Migration-based livelihoods in post-2000 Zimbabwe MANASE KUDZAI CHIWESHE 6 Agricultural production Systems of small-scale farmers in Hwedza in the context of Innovation platforms INNOCENT MAHIYA 7 Development NGOs: understanding participatory methods, accountability and effectiveness of World Vision in Umzingwane District KAYLA KNIGHT WAGHORN viii Contents 8 A critical analysis of Community participation at the primary level of the health System in Goromonzi District 124 RACHEL GONDO 9 Climate variability in local scales: narratives and ambivalences from Mutoko District 139 SANDRA BHATASARA 10 Livelihoods vulnerability among riverbed farmers in Negande, NyamiNyami District 154 FELIX TOMBINDO 11 "Let them starve so that they 'hear' us": differing perspectives on unresolved land occupations and livelihoods at Mushandike smallholder irrigation sehe nie, Masvingo District 170 JONATHAN MAFUK1DZE 12 "Other people inherit property, but I inherit people and their problems": the role of kinship and social capital in providing care and Support for the HIV infected and AIDS affected, Chivanhu informal settlement, Masvingo Province 184 LOVENESS MAKONESE 13 Insecure land tenure and natural resource use in a post-fast track area of Zimbabwe 198 TAKUNDA CHABATA 14 Fast track land reform programme and women in Goromonzi District 213 LOVENESS CHAKONA AND MANASE KU DZAI CHIWESHE Index 230 . -

Zimbabwe Market Study: Masvingo Province Report

©REUTERS/Philimon Bulawayo Bulawayo ©REUTERS/Philimon R E S E A R C H T E C H N I C A L A S S I S T A N C E C E N T E R January 2020 Zimbabwe Market Study: Masvingo Province Report Dominica Chingarande, Gift Mugano, Godfrey Chagwiza, Mabel Hungwe Acknowledgments The Research team expresses its gratitude to the various stakeholders who participated in this study in different capacities. Special gratitude goes to the District Food and Nutrition Committee members, the District Drought Relief Committee members, and various market actors in the province for providing invaluable local market information. We further express our gratitude to the ENSURE team in Masvingo for mobilizing beneficiaries of food assistance who in turn shared their lived experiences with food assistance. To these food assistance beneficiaries, we say thank you for freely sharing your experiences. Research Technical Assistance Center The Research Technical Assistance Center is a world-class research consortium of higher education institutions, generating rapid research for USAID to promote evidence-based policies and programs. The project is led by NORC at the University of Chicago in partnership with Arizona State University, Centro de Investigacin de la Universidad del Pacifico (Lima, Peru), Davis Management Group, the DevLab@Duke University, Forum One, the Institute of International Education, the Notre Dame Initiative for Global Development, Population Reference Bureau, the Resilient Africa Network at Makerere University (Kampala, Uganda), the United Negro College Fund, the University of Chicago, and the University of Illinois at Chicago. The Research Technical Assistance Center (RTAC) is made possible by the generous support of the American people through the United States Agency for International Development (USAID) under the terms of contract no. -

Rural District Planning in Zimbabwe: a Case Study

INTERNATIONAL INSTITUTE FOR ENVIRONMENT AND DEVELOPMENT Environmental Planning Issues No.23, December 2000 Local Strategic Planning and Sustainable Rural Livelihoods Rural District Planning in Zimbabwe: A Case Study By PlanAfric Bulawayo, Zimbabwe A Report to the UK Department for International Development (Research contract: R72510) PlanAfric Suite 416, 4th Floor, Treger House, 113 Jason Moyo Street PO Box FM 524, Famona, Bulawayo, Zimbabwe Tel/Fax: +263-9-66142; Email: [email protected] IIED 3 Endsleigh Street, London WC1H ODD Tel: +44-171-388-2117; Fax: +44-171-388-2826 Email: [email protected] Website: http://www.iied.org ISBN: 1 899825 76 2 NOTE This manuscript was completed in November 1999. It has not been possible to include any updates to the text to reflect any changes that might have occurred in terms of legislation, institutional arrangements and key issues. RURAL PLANNING REPORTS This report is one of a suite of four prepared for a study of rural planning experience globally, and published by IIED in its Environmental Planning Issues series: Botchie G. (2000) Rural District Planning in Ghana: A Case Study. Environmental Planning Issues No. 21, Internationa l Institute for Environment and Development, London Dalal-Clayton, D.B., Dent D.L. and Dubois O. (1999): Rural Planning in the Developing World with a Special Focus on Natural Resources: Lessons Learned and Potential Contributions to Sustainable Livelihoods: An Overview. Report to UK Department for International Development. Environmental Planning Issues No.20, IIED, London Khanya-mrc (2000) Rural planning in South Africa: A case study. A report prepared by Khanya – managing rural change, Bloemfontein. -

Masvingo Province

School Level Province Ditsrict School Name School Address Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIKITA FASHU SCH BIKITA MINERALS CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIKITA MAMUTSE SECONDARY MUCHAKAZIKWA VILLAGE CHIEF BUDZI BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita BIRIVENGE MUPAMHADZI VILLAGE WARD 12 CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita BUDIRIRO VILLAGE 1 WARD 11 CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHENINGA B WARD 2, CHF;MABIKA, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIKWIRA BETA VILLAGE,CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE,WARD 16 Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHINYIKA VILLAGE 23 DEVURE WARD 26 Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIPENDEKE CHADYA VILLAGE, CHF ZIKI, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIRIMA RUGARE VILLAGE WARD 22, CHIEF;MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIRUMBA TAKAWIRA VILLAGE, WARD 9, CHF; MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHISUNGO MBUNGE VILLAGE WARD 21 CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita CHIZONDO CHIZONDO HIGH,ZINDOVE VILLAGE,WARD 2,CHIEF MABIKA Secondary Masvingo Bikita FAMBIDZANAI HUNENGA VILLAGE Secondary Masvingo Bikita GWINDINGWI MABHANDE VILLAGE,CHF;MUKANGANWI, WRAD 13, BIKITA Secondary Masvingo Bikita KUDADISA ZINAMO VILLAGE, WARD 20,CHIEF MUKANGANWI Secondary Masvingo Bikita KUSHINGIRIRA MUKANDYO VILLAGE,BIKITA SOUTH, WARD 6 Secondary Masvingo Bikita MACHIRARA CHIWA VILLAGE, CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE Secondary Masvingo Bikita MANGONDO MUSUKWA VILLAGE WARD 11 CHIEF MAROZVA Secondary Masvingo Bikita MANUNURE DEVURE RESETTLEMENT VILLAGE 4A CHIEF BUDZI Secondary Masvingo Bikita MARIRANGWE HEADMAN NEGOVANO,CHIEF MAZUNGUNYE Secondary Masvingo Bikita MASEKAYI(BOORA) -

Pdf | 223.83 Kb

SOUTHERN AFRICA Flash Update No.6 – Tropical Cyclone Eloise As of 23 January 2021 HIGHLIGHTS • Tropical Cyclone Eloise made landfall near Beira City in Sofala Province, Mozambique in the early hours of 23 January. • After landfall, Eloise downgraded to a Moderate Tropical Storm bringing heavy rains and strong winds in Sofala Province. • The most immediate concern is the potential for significant flooding, including in the days ahead. • Eloise is expected to continue to move inland, bringing heavy rains to southern Zimbabwe, northern South Africa and far eastern Botswana. SITUATION OVERVIEW Tropical Cyclone Eloise made landfall in central Mozambique on 23 January at around 2 a.m., near the coastal city of Beira, with winds of 140 km/h and gusts up to 160 km/h, according to Mozambique’s National Institute of Meteorology (INAM). Beira received 250 mm of rain in 24 hours, according to INAM, while other areas that were flooded ahead of Eloise’s landfall—including Buzi and Nhamatanda—also received additional heavy rains. After landfall, Eloise downgraded to a moderate tropical storm with a maximum wind speed of 83 km/hr. The weather system continues to move in a westerly direction, bringing high amounts of rainfall in its wake, according to the South Africa Weather Services (SAWS). Luisa Meque, President of Mozambique’s National Institute for Disaster Risk Management and Reduction (INGD), has noted that it is too early to quantify the extent and scale of the destruction, but that the damage in Beira appears to be mild. Electricity was down in parts of the city and communications networks were damaged. -

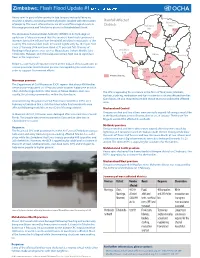

ZIM-Infographic-Flood-06 A4 07Feb2014 Zimbabwe Flash Flood - February 2014.Ai

¡ ¢ £ ¤ ¥ ¦ § ¨ © ¡ ¥ Heavy rains in parts of the country in late January and early February resulted in deaths and displacement of people, coupled with destruction Rainfall A!ected Mashonaland of property. The worst a!ected areas are Chivi and Masvingo districts in Districts Mashonaland Central Masvingo province and Tsholotsho district in Matabeleland North. West Shamva The Zimbabwe National Water Authority (ZINWA) in its hydrological Makonde Binga update on 5 February warned that the country’s dam levels continue to Harare increase due to the in"ows from the rainfall activities in most parts of the Gokwe South country. The national dam levels increased signicantly by 10.29 per cent since 27 January 2014 and now stand at 71 per cent full. Chances of Mashonaland "ooding in "ood prone areas such as Muzarabani, Gokwe, Middle Sabi, Matabeleland East Tsholotsho, Malapati and Chikwalakwala remain high due to signicant North Midlands Manicaland "ows in the major rivers. Tsholotsho Gutu Bulawayo Below is a summary of reports received on the impact of incessant rains in Masvingo Chivi various provinces. Humanitarian partners are appealing for assistance in Matabeleland Masvingo order to support Government e!orts. Mangwe South A!ected districts Gwanda Mwenezi Chiredzi Masvingo province The Department of Civil Protection (DCP) reports that about 400 families needed to be evacuated on 3 February while another 4,000 were at risk in Chivi and Masvingo districts after levels at Tokwe-Mukorsi dam rose The CPC is appealing for assistance in the form of food, tents, blankets, rapidly, threatening communities within the dam basin. buckets, clothing, medication and fuel in order to assist the a!ected families. -

Zimbabwe Total Financialzimbabwe Requirements Flash Appeal (Us$) Total People in Need Total People Targeted

FLASH 2019 APPEAL (Revised following Cyclone Idai, March 2019) January - June 2019 Photo: GOAL\Anteneh Tadele ZIMBABWE TOTAL FINANCIALZIMBABWE REQUIREMENTS FLASH APPEAL (US$) TOTAL PEOPLE IN NEED TOTAL PEOPLE TARGETED $294M 5.57M 2.47M FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS - FLOODS PEOPLE IN NEED - FLOODS PEOPLE TARGETED - FLOODS $60M 270K 270K FINANCIAL REQUIREMENTS - DROUGHT PEOPLE IN NEED - DROUGHT PEOPLE TARGETED - DROUGHT $234M 5.3M 2.2M MASHONALAND MASHONALAND CENTRAL WEST 0.3m Kariba! 0.4m MASHONALAND 0.3m HARARE EAST 260K 0.3m MIDLANDS MANICALAND MATABELELAND NORTH 02 0.4m 0.6m 10K BULAWAYO MASVINGO MATABELELAND SOUTH 0.4m 0.2m XX F insecur IPC Food Insecurity Phase 1 Mal XX P b 2 Sessed b ovince 3 A districts 4 Egency M 5 CatastrFamine A least e ! assistance Le Source: Zimbabwe IPC TWG This document is produced by the Humanitarian Country Team and the United Nations Resident Coordinator’s Office in Zimbabwe with the support of the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). The projects reflected here support the national government. It covers the period from January to June 2019. The Plan has been revised in March 2019 to incorporate the immediate response to needs arising from the impact of Cyclone Idai. JANUARY - JUNE 2019 TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD BY THE UN RESIDENT COORDINATOR 04 THE FLASH APPEAL AT A GLANCE 05 OVERVIEW OF THE CRISIS 06 RESPONSE STRATEGY AND STRATEGIC OBJECTIVES 11 RESPONSE STRATEGY AND CAPACITY 12 SUMMARY OF NEEDS, TARGETS & REQUIREMENTS 13 SECTOR RESPONSE PLANS AGRICULTURE -

Climate Change Impact, Adaptation and Mitigation in Zimbabwe.Indd

CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACT, ADAPTATION AND MITIGATION IN ZIMBABWE CASE STUDIES FROM ZIMBABWE’S URBAN AND RURAL AREAS Climate Change Impact, Adaptation and Mitigation in Zimbabwe Case Studies From Zimbabwe’s Urban and Rural Areas 2 Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung www.kas.de/simbabwe Climate Change Impact, Adaptation and Mitigation in Zimbabwe Case Studies From Zimbabwe’s Urban and Rural Areas Copyright © 2021 Kefasi Nyikahadzoi and Lindah Mhlanga English editorial by Professor Zifi kile Makwavarara Edited by : Kefasi Nyikahadzoi and Lindah Mhlanga PUBLISHED BY 26 Sandringham Drive - Alexandra Park P.O. Box 4325 Harare, Zimbabwe [email protected] | +263 242 744602 DESIGN ILLUSTRATIONS & LAYOUT OnaDsgn [email protected] | www.onadsgn.com Climate Change Impact, Adaptation and Mitigation in Zimbabwe Case Studies From Zimbabwe’s Urban and Rural Areas All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer, who may quote brief passages in a review. i Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung www.kas.de/simbabwe Climate Change Impact, Adaptation and Mitigation in Zimbabwe Case Studies From Zimbabwe’s Urban and Rural Areas Contributors Chapungu Lazarus is a PhD. holder and a Lecturer at the School of Natural Sciences, Great Zimbabwe University, Masvingo, Zimbabwe. His research interests include climate change mitigation, impacts and responses, with a bias towards ecosystem responses to climate change. Chikodzi David is an Associate Professor and a Lecturer in the Department of Physics, Geography and Environmental Science, School of Natural Sciences, Great Zimbabwe University, Masvingo, Zimbabwe. -

Accessibility of Healthcare in Rural Zimbabwe: the Perspective of Nurses and Healthcare Users

African Journal of Primary Health Care & Family Medicine ISSN: (Online) 2071-2936, (Print) 2071-2928 Page 1 of 7 Original Research Accessibility of healthcare in rural Zimbabwe: The perspective of nurses and healthcare users Authors: Background: Accessibility of healthcare in rural areas is globally impeded by physical, 1 Manenji Mangundu material, human, financial and managerial resources and societal barriers in the healthcare Lizeth Roets1 Elsie Janse van Rensberg1 system. Developing countries like Zimbabwe are significantly affected. Aim: The aim of this article was to share the perspectives of nurses and healthcare users Affiliation: 1Department of Health (HCUs) in the rural areas of Zimbabwe with regard to the accessibility of healthcare. Studies, School of Social Setting: The study was conducted at 45 rural health facilities in Chegutu district, Mashonaland Sciences, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa West province and Masvingo district in Masvingo province, Zimbabwe. Corresponding author: Methods: A self-administered questionnaire (for professional nurses) and a structured Manenji Mangundu, interview questionnaire (for HCUs) were utilised to gather data in a cross-sectional survey. [email protected] Two districts were randomly sampled from 59 districts. All nurses working in 45 public health facilities in the selected two districts, who were willing and available to participate, were Dates: included. Ninety nurses participated in the study. The HCUs were selected through a Received: 17 Sept. 2019 Accepted: 24 Feb. 2020 multistage sampling technique. The sample size for HCUs was calculated by using Dobson’s Published: 14 May 2020 formula, and 445 HCUs were included via convenience sampling. How to cite this article: Results: Nurses reported challenges such as work overload because of staffing shortages Mangundu M, Roets L, (55%) and the supply of necessary medical drugs that lacked consistency in both the quantity Janse van Rensberg E.