Lancaster Conservation Area Appraisal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lancaster-Cultural-Heritage-Strategy

Page 12 LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY REPORT FOR LANCASTER CITY COUNCIL Page 13 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ...........................................................................3 1 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................7 2 THE CONTEXT ................................................................................10 3 RECENT VISIONING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 24 4 HOW LANCASTER COMPARES AS A HERITAGE CITY...............28 5 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S BUILT FABRIC .....................................32 6 LANCASTER DISTRICT’S CULTURAL HERITAGE ATTRACTIONS39 7 THE MANAGEMENT OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE 48 8 THE MARKETING OF LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE.....51 9 CONCLUSIONS: SWOT ANALYSIS................................................59 10 AIMS AND OBJECTIVES FOR LANCASTER’S CULTURAL HERITAGE .......................................................................................65 11 INVESTMENT OPTIONS..................................................................67 12 OUR APPROACH TO ASSESSING ECONOMIC IMPACT ..............82 13 TEN YEAR INVESTMENT FRAMEWORK .......................................88 14 ACTION PLAN ...............................................................................107 APPENDICES .......................................................................................108 2 Page 14 BLUE SAIL LANCASTER CULTURAL HERITAGE STRATEGY MARCH 2011 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Lancaster is widely recognised -

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Charter Index 1874-1973

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Charter Index 1874-1973 Transcribed from index books within the Lancaster County Archives collection Name of Organization Book Page Office 316th Infantry Association 1 57 Prothonotary 316th Infantry Association 3 57 Prothonotary A. B. Groff & Sons 4 334 Recorder of Deeds A. B. Hess Cigar Co., Inc. 2 558 Recorder of Deeds A. Buch's Sons' & Co. 2 366 Recorder of Deeds A. H. Hoffman Inc. 3 579 Recorder of Deeds A. M. Dellinger, Inc. 6 478 Recorder of Deeds A. N. Wolf Shoe Company (Denver, PA) 6 13 Recorder of Deeds A. N. Wolf Shoe Company (Miller Hess & Co. Inc.) (merger) R-53 521 Recorder of Deeds A. P. Landis Inc. 6 554 Recorder of Deeds A. P. Snader & Company 3 3 Recorder of Deeds A. S. Kreider Shoe Manufacturing Co. 5 576 Recorder of Deeds A. T. Dixon Inc. 5 213 Recorder of Deeds Academy Sacred Heart 1 151 Recorder of Deeds Acme Candy Pulling Machine Co. 2 290 Recorder of Deeds Acme Metal Products Co. 5 206 Recorder of Deeds Active Social & Beneficial Association 5 56 Recorder of Deeds Active Social and Beneficial Association 2 262 Prothonotary Actor's Company 5 313 Prothonotary Actor's Company (amendment) 5 423 Prothonotary Adahi Hunting Club 5 237 Prothonotary Adams and Perry Watch Manufacturing Co., Lancaster 1 11 Recorder of Deeds Adams and Perry Watch Manufacturing Co., Lancaster (amendment) 1 46 Recorder of Deeds Adams County Girl Scout Council Inc. (Penn Laurel G. S. Council Inc.) E-51 956 Recorder of Deeds Adamstown Bicentennial Committee Inc. 4 322 Prothonotary Adamstown Bicentennial Committee Inc. -

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

Lancaster Castle: the Rebuilding of the County Gaol and Courts

Contrebis 2019 v37 LANCASTER CASTLE: THE REBUILDING OF THE COUNTY GAOL AND COURTS John Champness Abstract This paper details the building and rebuilding of Lancaster Castle in the late-eighteenth and early- nineteenth centuries to expand and improve the prison facilities there. Most of the present buildings in the Castle date from a major scheme of extending the County Gaol, undertaken in the last years of the eighteenth century. The principal architect was Thomas Harrison, who had come to Lancaster in 1782 after winning the competition to design Skerton Bridge (Champness 2005, 16). The scheme arose from concern about the unsatisfactory state of the Gaol which was largely unchanged from the medieval Castle (Figure 1). Figure 1. Plan of Lancaster Castle taken from Mackreth’s map of Lancaster, 1778 People had good reasons for their concern, because life in Georgian gaols was somewhat disorganised. The major reason lay in how the role of gaols had been expanded over the years in response to changing pressures. County gaols had originally been established in the Middle Ages to provide short-term accommodation for only two groups of people – those awaiting trial at the twice- yearly Assizes, and convicted criminals who were waiting for their sentences to be carried out, by hanging or transportation to an overseas colony. From the late-seventeenth century, these people were joined by debtors. These were men and women with cash-flow problems, who could avoid formal bankruptcy by forfeiting their freedom until their finances improved. During the mid- eighteenth century, numbers were further increased by the imprisonment of ‘felons’, that is, convicted criminals who had not been sentenced to death, but could not be punished in a local prison or transported. -

The First 40 Years

A HISTORY OF LANCASTER CIVIC SOCIETY THE FIRST 40 YEARS 1967 – 2007 By Malcolm B Taylor 2009 Serialization – part 7 Territorial Boundaries This may seem a superfluous title for an eponymous society, so a few words of explanation are thought necessary. The Society’s sometime reluctance to expand its interests beyond the city boundary has not prevented a more elastic approach when the situation demands it. Indeed it is not true that the Society has never been prepared to look beyond the City boundary. As early as 1971 the committee expressed a wish that the Society might be a pivotal player in the formation of amenity bodies in the surrounding districts. It was resolved to ask Sir Frank Pearson to address the Society on the issue, although there is no record that he did so. When the Society was formed, and, even before that for its predecessor, there would have been no reason to doubt that the then City boundary would also be the Society’s boundary. It was to be an urban society with urban values about an urban environment. However, such an obvious logic cannot entirely define the part of the city which over the years has dominated the Society’s attentions. This, in simple terms might be described as the city’s historic centre – comprising largely the present Conservation Areas. But the boundaries of this area must be more fluid than a simple local government boundary or the Civic Amenities Act. We may perhaps start to come to terms with definitions by mentioning some buildings of great importance to Lancaster both visually and strategically which have largely escaped the Society’s attentions. -

St. Paul's Church, Scotforth

St. Paul’s Church, Scotforth Contents Summary 2 Our Vision 3 Who Is God Calling? 3 The Parish and Wider Community 4 Church Organization 7 The Church Community 8 Together we are stronger 10 Our Buildings 11 The Church 12 The Hala Centre 13 The Parish Hall 14 The Vicarage 15 The Church Finances 16 Our Schools 17 Our Links into the Wider Community 20 1 Summary St Paul’s Church Scotforth is a vibrant and accepting community in Lancaster. The church building is a landmark on the A6 south of the city centre, and the vicarage is adjacent in its own private grounds. Living here has many attractive features. We have our own outstanding C of E primary school nearby with which we have strong links. And very close to the parish we also find outstanding secondary schools, Ripley C of E academy and two top-rated grammar schools. In addition Lancaster’s two universities bring lively people and facilities to the area. Traveling to and from Scotforth has many possibilities. We rapidly connect to the M6 and to the west coast main train line. Our proximity to beautiful countryside keeps many residents happy to remain. We are close to the Lake District, the Yorkshire Dales, Bowland forest, Morecambe Bay, to mention just a few such attractions. Our Church is a welcoming and friendly place. Our central churchmanship is consistent with the lack of a central aisle in our unusual “pot” church building! Our regular services (BCP or traditional, in church or in the Hala Centre) use the Bible lectionary to encourage understanding and action, but we also are keen to develop innovative forms of worship. -

A History of Lancaster and District Male Voice Choir

A History of Lancaster and District Male Voice Choir From 1899 to 2013 this history is based on the writings of Roland Brooke and the first history contained in the original website (no longer operational). From 2013 it is the work of Dr Hugh Cutler sometime Chairman and subsequently Communications Officer and editor of the website. The Years 1899-1950 The only indication of the year of foundation is that 1899 is mentioned in an article in the Lancaster Guardian dated 13th November 1926 regarding the Golden Wedding Anniversary of Mr. & Mrs. R.T. Grosse. In this article it states that he was 'for many years the Conductor of the Lancaster Male Voice Choir which was formed at the end of 1899'. The Guardian in February 1904 reported that 'the Lancaster Male Voice Choir, a new organisation in the Borough, are to be congratulated on the success of their first public concert'. The content of the concert was extensive with many guest artistes including a well-known soprano at that time, Madame Sadler-Fogg. In the audience were many honoured guests, including Lord Ashton, Colonel Foster, and Sir Frederick Bridge. In his speech, the latter urged the Choir to 'persevere and stick together'. Records state that the Choir were 'at their zenith' in 1906! This first public concert became an annual event, at varying venues, and their Sixth Annual Concert was held in the Ashton Hall in what was then known as 'The New Town Hall' in Lancaster. This was the first-ever concert held in 'The New Town Hall', and what would R.T. -

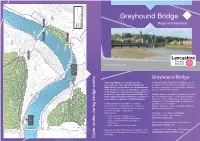

Greyhound Bridge for Buses Or Cycle S No Right Turn

y FS High School 10.7m Fleming House y N Stewart 97 to 107 Court masonr g in p Skerton Tide Gauge lo Learning S Centre 1 to h PH 3 t OWEN ROAD Pa Lune Park Rigg House Childrens Centre Mast (Telecommunication) Y MAINWA Mud 1 Acre Court 11.0m to Path o 91 10.7m t 3 AR Centre 65 Ellershaw House 5 ath e Ryelands cle P RYELANDS PARK ingl Cy 1 347050 347100 16 347150 347200 347250 347300 347350 347400 347450 347500 347550 347600 347650 347700 347750 347800 347850 347900 347950 348000 348050 348100 Dr a 462600N 348150E 1 in E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E ST LUKE'S to and Sh 3 Mud CHURCH Greg House 6 Bandstand 63 L AD 4 IES 1 53 to W Miller 12 St Luke's Court 12.5m Church 33 1 to 3 Frankland House 15 Park Church Court 462550N rise Garage 11.9m p 41 to 51 r 7.3m 22 e ake Ente 1 L Shards Court to FATHERS HOUSE 11 39 Bridg d Shingl 12 e Hou e ELIM CHURCH 13 to se Mud an 23 d Shingl RS 27 ST Mud an 14 462500N Kiln 10.1m Court to 11 7.3m 1 MORECAMBE ROAD n Drai D OA R E REVISEDRevised JUNCTION junction 6.7m e CATON 462450N hingl S NCN 69 footway/ Car Park NCN 69 FOOTWAY / ud and cycleway open at Mud M CYCLEWAY OPEN AT RIVERWAY all times HOUSE Carlisle ALL TIMES e Bridge MORECAMBE ROAD ingl Co Const, ED & Ward Underpass y CCLW Mud and Sh Bdy OUR LADY'S cle Wa Cy 462400N CARLISLE BRIDG CARLISLE CATHOLIC COLLEGE Sewage Pumping SKERTON BRIDG r e Station t 7.9m Rock and Mud 7.6m Wa h g 201 to 207 an Hi 301 to 313 Me 401 to 420 501 to 520 Y North A 601 to 620 View Me SW 701 to 720 G a n High N KI The Old Bus Depot Wate 29 E 93 6.4m ST GEOR -

Your District Council Matters Issue 37

Your District Council Matters Lancaster City Council’s Community Magazine Issue 37 • Spring/Summer 2020 How we’re tackling the Inside climate emergency People’s Jury tackles climate change Flood protection scheme gets underway Plastic fantastic – help us to recycle even more Taking to the streets to help the homeless @lancastercc facebook.com/lancastercc lancaster.gov.uk 2 | Your District Council Matters Spring/Summer 2020 E O M W E L C from Councillor Dr Erica Lewis, leader of Lancaster City Council I’m Erica, and since last May I’ve been the new leader of the city council. I will have met some of you while I’ve been out knocking doors across the district, but thought I’d take this opportunity to introduce myself to everyone else. For more than two decades, I’ve worked I’m passionate about mobilising the skills, and volunteered as a director and trustee talents and wisdom of everyone. So it in the charitable sector, through which is important to me that as a council, we I developed a deep understanding of make sure we’re better connected to every good governance and sound financial neighbourhood across the district. management. We’re looking for ways to build new I’ve also been a Lancashire County partnerships and collaborations to tackle Councillor since 2017; work which big challenges like the climate emergency requires attention to detail (and a bit of a and revitalising our high streets. fascination with sorting out potholes and We all want our district to be a great place blocked drains!). -

Lancaster City Council Multi-Agency Flooding Plan

MAFP PTII Lancaster V3.2 (Public) June 2020 Lancaster City Council Multi-Agency Flooding Plan Emergency Call Centre 24-hour telephone contact number 01524 67099 Galgate 221117 Date June 2020 Current Version Version 3.2 (Public) Review Date March 2021 Plan Prepared by Mark Bartlett Personal telephone numbers, addresses, personal contact details and sensitive locations have been removed from this public version of the flooding plan. MAFP PTII Lancaster V3.2 (Public version) June 2020 CONTENTS Information 2 Intention 3 Intention of the plan 3 Ownership and Circulation 4 Version control and record of revisions 5 Exercises and Plan activations 6 Method 7 Environment Agency Flood Warning System 7 Summary of local flood warning service 8 Surface and Groundwater flooding 9 Rapid Response Catchments 9 Command structure and emergency control rooms 10 Role of agencies 11 Other Operational response issues 12 Key installations, high risk premises and operational sites 13 Evacuation procedures (See also Appendix ‘F’) 15 Vulnerable people 15 Administration 16 Finance, Debrief and Recovery procedures Communications 16 Equipment and systems 16 Press and Media 17 Organisation structure and communication links 17 Appendix ‘A’ Cat 1 Responder and other Contact numbers 18 Appendix ‘B’ Pumping station and trash screen locations 19 Appendix ‘C’ Sands bags and other Flood Defence measures 22 Appendix ‘D’ Additional Council Resources for flooding events 24 Appendix ‘E’ Flooding alert/warning procedures - Checklists 25 Appendix ‘F’ Flood Warning areas 32 Lancaster -

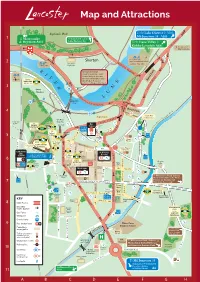

Map and Attractions

Map and Attractions 1 & Heysham to Lancaster City Park & Ride to Crook O’Lune, 2 Skerton t River Lune Millennium Park and Lune Aqueduct Bulk Stree N.B. Greyhound Bridge closed for works Jan - Sept. Skerton Bridge to become two-way. Other trac routes also aected. Please see Retail Park www.lancashire.gov.uk for details 3 Quay Meadow re Ay en re e Park G kat S 4 Retail Park Superstore Vicarage Field Buses & Taxis . only D R Escape H T Room R NO Long 5 Stay Buses & Taxis only Cinema LANCASTER VISITOR Long 6 INFORMATION CENTRE Stay e Gregson Th rket Street Centre Storey Ma Bashful Alley Sir Simons Arcade Long 7 Stay Long Stay Buses & Taxis only Magistrates 8 Court Long Stay 9 /Stop l Cruise Cana BMI Hospital University 10 Hospital of Cumbria visitors 11 AB CDEFG H ATTRACTIONS IN AND Assembly Rooms Lancaster Leisure Park Peter Wade Guided Walks AROUND LANCASTER Built in 1759, the emporium houses Wyresdale Road, Lancaster, LA1 3LA A series of interesting themed walks an eclectic mix of stalls. 01524 68444 around the district. Lancaster Castle lancasterleisurepark.com King Street, Lancaster, LA1 1LG 01524 420905 Take a guided tour and step into a 01524 414251 - GB Antiques Centre visitlancaster.org.uk/whats-on/guided- thousand years of history. lancaster.gov.uk/assemblyrooms Open 10:00 – 17:00 walks-with-peter-wade/ Adults £1.50, Children/OAP 75p, Castle Park, Lancaster, LA1 1YJ Tuesday–Saturday 10:00 - 16:30 Under 5s Free Various dates, start time 2pm. 01524 64998 Closed all Bank Holidays Trade Dealers Free Tickets £3 lancastercastle.com - Lancaster Brewery Castle Grounds open 09:30 – 17:00 daily King Street Studios Monday-Thursday 10:00 - 17:00 Lune Aqueduct Open for guided tours 10:00 – 16:00 Exhibition space and gallery showing art Friday- Sunday 10:00 – 18:00 Take a Lancaster Canal Boat Cruise (some restrictions, please check with modern and contemporary values. -

The Medical Pioneers of Nineteenth Century Lancaster

The Medical Pioneers of Nineteenth Century Lancaster The Medical Pioneers of Nineteenth Century Lancaster Edited by Quenton Wessels The Medical Pioneers of Nineteenth Century Lancaster Edited by Quenton Wessels First edition by epubli GmbH Berlin 2016 ISBN (13): 978-3-7418-0717-6 This revised edition by Cambridge Scholars Publishing 2018 Lady Stephenson Library, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2PA, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2018 by Quenton Wessels and contributors All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-5275-0819-6 ISBN (13): 978-1-5275-0819-4 This book is dedicated to the Pioneers at Lancaster Medical School CONTENTS List of Figures............................................................................................. ix List of Tables .............................................................................................. xi List of Abbreviations ................................................................................ xiii Acknowledgements ................................................................................... xv Chapter One ................................................................................................. 1 Introduction Quenton Wessels Chapter Two ...............................................................................................