Lancaster Castle: the Rebuilding of the County Gaol and Courts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Charter Index 1874-1973

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Charter Index 1874-1973 Transcribed from index books within the Lancaster County Archives collection Name of Organization Book Page Office 316th Infantry Association 1 57 Prothonotary 316th Infantry Association 3 57 Prothonotary A. B. Groff & Sons 4 334 Recorder of Deeds A. B. Hess Cigar Co., Inc. 2 558 Recorder of Deeds A. Buch's Sons' & Co. 2 366 Recorder of Deeds A. H. Hoffman Inc. 3 579 Recorder of Deeds A. M. Dellinger, Inc. 6 478 Recorder of Deeds A. N. Wolf Shoe Company (Denver, PA) 6 13 Recorder of Deeds A. N. Wolf Shoe Company (Miller Hess & Co. Inc.) (merger) R-53 521 Recorder of Deeds A. P. Landis Inc. 6 554 Recorder of Deeds A. P. Snader & Company 3 3 Recorder of Deeds A. S. Kreider Shoe Manufacturing Co. 5 576 Recorder of Deeds A. T. Dixon Inc. 5 213 Recorder of Deeds Academy Sacred Heart 1 151 Recorder of Deeds Acme Candy Pulling Machine Co. 2 290 Recorder of Deeds Acme Metal Products Co. 5 206 Recorder of Deeds Active Social & Beneficial Association 5 56 Recorder of Deeds Active Social and Beneficial Association 2 262 Prothonotary Actor's Company 5 313 Prothonotary Actor's Company (amendment) 5 423 Prothonotary Adahi Hunting Club 5 237 Prothonotary Adams and Perry Watch Manufacturing Co., Lancaster 1 11 Recorder of Deeds Adams and Perry Watch Manufacturing Co., Lancaster (amendment) 1 46 Recorder of Deeds Adams County Girl Scout Council Inc. (Penn Laurel G. S. Council Inc.) E-51 956 Recorder of Deeds Adamstown Bicentennial Committee Inc. 4 322 Prothonotary Adamstown Bicentennial Committee Inc. -

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

A History of Lancaster and District Male Voice Choir

A History of Lancaster and District Male Voice Choir From 1899 to 2013 this history is based on the writings of Roland Brooke and the first history contained in the original website (no longer operational). From 2013 it is the work of Dr Hugh Cutler sometime Chairman and subsequently Communications Officer and editor of the website. The Years 1899-1950 The only indication of the year of foundation is that 1899 is mentioned in an article in the Lancaster Guardian dated 13th November 1926 regarding the Golden Wedding Anniversary of Mr. & Mrs. R.T. Grosse. In this article it states that he was 'for many years the Conductor of the Lancaster Male Voice Choir which was formed at the end of 1899'. The Guardian in February 1904 reported that 'the Lancaster Male Voice Choir, a new organisation in the Borough, are to be congratulated on the success of their first public concert'. The content of the concert was extensive with many guest artistes including a well-known soprano at that time, Madame Sadler-Fogg. In the audience were many honoured guests, including Lord Ashton, Colonel Foster, and Sir Frederick Bridge. In his speech, the latter urged the Choir to 'persevere and stick together'. Records state that the Choir were 'at their zenith' in 1906! This first public concert became an annual event, at varying venues, and their Sixth Annual Concert was held in the Ashton Hall in what was then known as 'The New Town Hall' in Lancaster. This was the first-ever concert held in 'The New Town Hall', and what would R.T. -

Court Reform in England

Comments COURT REFORM IN ENGLAND A reading of the Beeching report' suggests that the English court reform which entered into force on 1 January 1972 was the result of purely domestic considerations. The members of the Commission make no reference to the civil law countries which Great Britain will join in an important economic and political regional arrangement. Yet even a cursory examination of the effects of the reform on the administration of justice in England and Wales suggests that English courts now resemble more closely their counterparts in Western Eu- rope. It should be stated at the outset that the new organization of Eng- lish courts is by no means the result of the 1971 Act alone. The Act crowned the work of various legislative measures which have brought gradual change for a period of well over a century, including the Judicature Acts 1873-75, the Interpretation Act 1889, the Supreme Court of Judicature (Consolidation) Act 1925, the Administration of Justice Act 1933, the County Courts Act 1934, the Criminal Appeal Act 1966 and the Criminal Law Act 1967. The reform culminates a prolonged process of response to social change affecting the legal structure in England. Its effect was to divorce the organization of the courts from tradition and history in order to achieve efficiency and to adapt the courts to new tasks and duties which they must meet in new social and economic conditions. While the earlier acts, including the 1966 Criminal Appeal Act, modernized the structure of the Supreme Court of Judicature, the 1971 Act extended modern court structure to the intermediate level, creating the new Crown Court, and provided for the regular admin- istration of justice in civil matters by the High Court in England and Wales, outside the Royal Courts in London. -

CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Undertaken August 2007

CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Undertaken August 2007 Promoting Improvement in Criminal Justice HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Undertaken August 2007 Promoting Improvement in Criminal Justice HM Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate CPS Sussex Overall Performance Assessment Report 2007 ABBREVIATIONS Common abbreviations used in this report are set out below. Local abbreviations are explained in the report. ABM Area Business Manager HMCPSI Her Majesty’s Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate ABP Area Business Plan JDA Judge Directed Acquittal AEI Area Effectiveness Inspection JOA Judge Ordered Acquittal ASBO Anti-Social Behaviour Order JPM Joint Performance Monitoring BCU Basic Command Unit or Borough Command Unit LCJB Local Criminal Justice Board BME Black and Minority Ethnic MAPPA Multi-Agency Public Protection Arrangements CCP Chief Crown Prosecutor MG3 Form on which a record of the CJA Criminal Justice Area charging decision is made CJS Criminal Justice System NCTA No Case to Answer CJSSS Criminal Justice: Simple, Speedy, NRFAC Non Ring-Fenced Administrative Summary Costs CJU Criminal Justice Unit NWNJ No Witness No Justice CMS Case Management System OBTJ Offences Brought to Justice CPIA Criminal Procedure and OPA Overall Performance Assessment Investigations Act PCD Pre-Charge Decision CPO Case Progression Officer PCMH Plea and Case Management Hearing CPS Crown Prosecution Service POCA Proceeds of Crime Act CPSD CPS Direct PTPM Prosecution Team Performance CQA Casework -

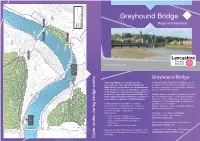

Greyhound Bridge for Buses Or Cycle S No Right Turn

y FS High School 10.7m Fleming House y N Stewart 97 to 107 Court masonr g in p Skerton Tide Gauge lo Learning S Centre 1 to h PH 3 t OWEN ROAD Pa Lune Park Rigg House Childrens Centre Mast (Telecommunication) Y MAINWA Mud 1 Acre Court 11.0m to Path o 91 10.7m t 3 AR Centre 65 Ellershaw House 5 ath e Ryelands cle P RYELANDS PARK ingl Cy 1 347050 347100 16 347150 347200 347250 347300 347350 347400 347450 347500 347550 347600 347650 347700 347750 347800 347850 347900 347950 348000 348050 348100 Dr a 462600N 348150E 1 in E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E E ST LUKE'S to and Sh 3 Mud CHURCH Greg House 6 Bandstand 63 L AD 4 IES 1 53 to W Miller 12 St Luke's Court 12.5m Church 33 1 to 3 Frankland House 15 Park Church Court 462550N rise Garage 11.9m p 41 to 51 r 7.3m 22 e ake Ente 1 L Shards Court to FATHERS HOUSE 11 39 Bridg d Shingl 12 e Hou e ELIM CHURCH 13 to se Mud an 23 d Shingl RS 27 ST Mud an 14 462500N Kiln 10.1m Court to 11 7.3m 1 MORECAMBE ROAD n Drai D OA R E REVISEDRevised JUNCTION junction 6.7m e CATON 462450N hingl S NCN 69 footway/ Car Park NCN 69 FOOTWAY / ud and cycleway open at Mud M CYCLEWAY OPEN AT RIVERWAY all times HOUSE Carlisle ALL TIMES e Bridge MORECAMBE ROAD ingl Co Const, ED & Ward Underpass y CCLW Mud and Sh Bdy OUR LADY'S cle Wa Cy 462400N CARLISLE BRIDG CARLISLE CATHOLIC COLLEGE Sewage Pumping SKERTON BRIDG r e Station t 7.9m Rock and Mud 7.6m Wa h g 201 to 207 an Hi 301 to 313 Me 401 to 420 501 to 520 Y North A 601 to 620 View Me SW 701 to 720 G a n High N KI The Old Bus Depot Wate 29 E 93 6.4m ST GEOR -

Your District Council Matters Issue 37

Your District Council Matters Lancaster City Council’s Community Magazine Issue 37 • Spring/Summer 2020 How we’re tackling the Inside climate emergency People’s Jury tackles climate change Flood protection scheme gets underway Plastic fantastic – help us to recycle even more Taking to the streets to help the homeless @lancastercc facebook.com/lancastercc lancaster.gov.uk 2 | Your District Council Matters Spring/Summer 2020 E O M W E L C from Councillor Dr Erica Lewis, leader of Lancaster City Council I’m Erica, and since last May I’ve been the new leader of the city council. I will have met some of you while I’ve been out knocking doors across the district, but thought I’d take this opportunity to introduce myself to everyone else. For more than two decades, I’ve worked I’m passionate about mobilising the skills, and volunteered as a director and trustee talents and wisdom of everyone. So it in the charitable sector, through which is important to me that as a council, we I developed a deep understanding of make sure we’re better connected to every good governance and sound financial neighbourhood across the district. management. We’re looking for ways to build new I’ve also been a Lancashire County partnerships and collaborations to tackle Councillor since 2017; work which big challenges like the climate emergency requires attention to detail (and a bit of a and revitalising our high streets. fascination with sorting out potholes and We all want our district to be a great place blocked drains!). -

Request for Transcription of Court Or Tribunal Proceedings

EX107GN Guidance Notes – Request for Transcription of Court or Tribunal proceedings If you want a transcript of proceedings in any court or tribunal (except the Court of Appeal Criminal Division or the Administrative Court*), please complete form EX107. If you want to order a transcript for more than one case, please complete a separate form EX107 for each different case in which you’re interested. Please note that not all Tribunals record proceedings so transcription services may not be available. Enquiries should be made to the relevant tribunal prior to completion of this form. EX107 can be sent digitally or by post to the court or tribunal. Contract details for the relevant venue can be obtained via Court Finder at https://courttribunalfinder.service.gov.uk/search/ For Civil and Family jurisdictions where you are selecting a transcription company, you are advised to talk with the transcription company before you complete form EX107. If an EX107 is requested by your chosen transcription company this should, where possible, be sent digitally using the e-mail addresses in Section 2a. You may send by post if you do not have an e-mail account. There may be occasions where a transcript you have requested via the EX107 may have already been produced for HMCTS. There may also be times where the court’s authorised Transcription Company provided a stenographer or court logger to make a record of the proceedings. In these circumstances the court’s authorised Transcription Company will provide the transcript and the court will tell you who to contact. Where a transcript is required of a court hearing which was held in private (ex parte) the process will vary by jurisdiction as follows: a) In cases heard at the Royal Courts of Justice and Crown Courts and some tribunals (or if the Court so orders at other venues), where a transcript is required of Court proceedings which were officially designated by the judge as being held in private (ex-parte), authorisation will be required from a Judge. -

[email protected]

Briefing and Business Estates Directorate 4th Floor, 102 Petty France LONDON SW1H 9AJ 020 3334 2632 E [email protected] Pat James C/o: [email protected] Our ref: FOI/106672 18 August 2016 Dear Mr James Thank you for your email of 23 July, in which you asked for the following information from the Ministry of Justice (MOJ): “All relevant recorded documentation of the locations within the United Kingdom where G4S provide 'Court Security Officer' services to HMCTS”. Your request has been handled under the Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA). I can confirm that the MOJ holds the information you requested and I am pleased to provide this to you by way of the attached annex. You can also find more information by reading the full text of the FOIA, available at http://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2000/36/contents). You have the right to appeal this decision if you think it is incorrect or if your request has been handled incorrectly. Details can be found in the ‘How to Appeal’ section attached to this letter. Disclosure Log You can also view information that the MOJ has disclosed in response to previous FOI requests. Responses are anonymised and published on our on-line disclosure log which can be found on the MoJ website: https://www.gov.uk/government/organisations/ministry-of- justice/series/freedom-of-information-disclosure-log Yours sincerely Signed by Darren Fearnley Annex HMCTS sites where security is provided by G4S Building Name Address Aberdeen Tribunal Atholl House, 84-86 Guild Street, Aberdeen -

Change at Lewes Crown Court

News from the South Eastern Circuit THE CIRCUITEER INSIDE THIS ISSUE 8 9 10 12 19 Meeting of the Inns of Court John Downes 23rd Keble A view from the Chairs of the College of Alliot a tribute Course Naval Bar SEC Bar Messes Advocacy (ICCA) ALL CHANGE AT LEADER’S LEWES CROWN REPORT And so, the time has come for me to bid farewell as Leader of COURT this great Circuit. 2016 has been a time of change across Max Hill QC See page 3 the whole of the Criminal Justice System. Lewes Crown Court has seen significant change, with its three most experienced judges retiring in the space of a few months. See page 6 Wellbeing at the Bar Does our wellbeing depend on the respite we all seek to find in holidays or should it be more a part of our daily lives even whilst working. Valerie Charbit See page 22 Reflections of a Circuiteer CIRCUIT TRIP TO PARIS I was called to the Bar in 1963. To practice It has been a number of years since the last circuit trip, and at what was then called the Independent many more since the last to Paris. This diplomatic mission Bar, whether you intended to venture out was long overdue, and, as we discovered from the moment of London or not, you were required to we arrived, a venture enthusiastically welcomed by our join a Circuit. Parisian counterparts. See page 14 See page 5 Igor Judge THE CIRCUITEER Issue 42 / October 2016 1 News from the South Eastern Circuit EDITOR’S COLUMN Much has happened across or friends, we are reminded • 88% of trans people have the Circuit since the Spring of the transient nature of our experienced depression edition, with changes of flickering flames. -

The First World War

OTHER PLACES OF INTEREST Lancaster & Event Highlights NOW AND THEN – LINKING PAST WITH THE PRESENT… Westfield War Memorial Village The First The son of the local architect, Thomas Mawson, was killed in April Morecambe District 1915 with the King’s Own. The Storey family who provided the land of World War Sat Jun 21 – Sat Oct 18 Mon Aug 4 Wed Sep 3 Sat Nov 8 the Westfield Estate and with much local fundraising the village was First World War Centenary War! 1914 – Lancaster and the Kings Own 1pm - 2pm Origins of the Great War All day ‘Britons at War 1914 – 1918’ 7:30pm - 10pm Lancaster and established in the 1920s and continued to be expanded providing go to War, Exhibition Lunchtime Talk by Paul G.Smith District Male Voice Choir Why remember? Where: Lancaster City Museum, Market Where: Lancaster City Museum, Where: Barton Road Community Centre, Where: The Chapel, University accommodation for soldiers and their families. The village has it’s Square, Lancaster Market Square, Lancaster Barton Road, Bowerham, Lancaster. of Cumbria, Lancaster own memorial, designed by Jennifer Delahunt, the art mistress at Tel: 01524 64637 T: 01524 64637 Tel: 01524 751504 Tel: 01524 582396 EVENTS, ACTIVITIES AND TRAIL GUIDE the Storey Institute, which shows one soldier providing a wounded In August 2014 the world will mark the one hundredth Sat Jun 28 Mon Aug 4 Sat Sep 6 Sun Nov 9 soldier with a drink, not the typical heroic memorial one usually anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. All day Meet the First World War Soldier 7pm - 9pm “Your Remembrances” Talk All day Centenary of the Church Parade of 11am Remembrance Sunday But why should we remember? Character at the City Museum Where: Meeting Room, King’s Own Royal the ‘Lancaster Pals’ of the 5th Battalion, Where: Garden of Remembrance, finds. -

A Barrister's Role in the Plea Decision

A Barrister’s Role in the Plea Decision: An analysis of drivers affecting advice in the Crown Court By James Dominic Edward Barry Queen Mary, University of London Submitted for PhD I declare that the work presented in this thesis is my own …………………………………. Date: ……………………………. James D.E Barry 2 Abstract: This thesis explores the reasons behind barristers' advice to defendants in the Crown Court on plea, primarily through interviews with criminal law practitioners themselves. Beginning with a critical overview of the current research, the thesis argues that the views of criminal barristers are a neglected significant source of information in developing an understanding of why particular advice is given. The thesis, in the context of other research, analyses the data from interviews conducted with current practitioners on the London and the Midlands Circuits, and discusses the various drivers that act upon barristers in deciding what advice to give. Starting with the actual advice given and the advising styles adopted, the thesis explores why guilty pleas might be advised and plea bargains sought with prosecutors. The research goes on to examine the impact of various influences, including legal, ethical, cultural, regional and financial to produce an overview of what factors impact upon a barrister's advice. The thesis argues that the current view of the Bar sustained in much of the literature is insufficiently nuanced and outdated, and that the reasons behind the advice given to defendants on plea are extraordinarily varied, occasionally contradictory, and highly complex. The thesis concludes that the data from the interviews warrants a rethink of why particular advice is given and that discovering what drives barristers’ advice is critical to formulating law and government policy.