Lancaster Castle and the British Civil Wars, 1642–1651

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Charter Index 1874-1973

Lancaster County, Pennsylvania Charter Index 1874-1973 Transcribed from index books within the Lancaster County Archives collection Name of Organization Book Page Office 316th Infantry Association 1 57 Prothonotary 316th Infantry Association 3 57 Prothonotary A. B. Groff & Sons 4 334 Recorder of Deeds A. B. Hess Cigar Co., Inc. 2 558 Recorder of Deeds A. Buch's Sons' & Co. 2 366 Recorder of Deeds A. H. Hoffman Inc. 3 579 Recorder of Deeds A. M. Dellinger, Inc. 6 478 Recorder of Deeds A. N. Wolf Shoe Company (Denver, PA) 6 13 Recorder of Deeds A. N. Wolf Shoe Company (Miller Hess & Co. Inc.) (merger) R-53 521 Recorder of Deeds A. P. Landis Inc. 6 554 Recorder of Deeds A. P. Snader & Company 3 3 Recorder of Deeds A. S. Kreider Shoe Manufacturing Co. 5 576 Recorder of Deeds A. T. Dixon Inc. 5 213 Recorder of Deeds Academy Sacred Heart 1 151 Recorder of Deeds Acme Candy Pulling Machine Co. 2 290 Recorder of Deeds Acme Metal Products Co. 5 206 Recorder of Deeds Active Social & Beneficial Association 5 56 Recorder of Deeds Active Social and Beneficial Association 2 262 Prothonotary Actor's Company 5 313 Prothonotary Actor's Company (amendment) 5 423 Prothonotary Adahi Hunting Club 5 237 Prothonotary Adams and Perry Watch Manufacturing Co., Lancaster 1 11 Recorder of Deeds Adams and Perry Watch Manufacturing Co., Lancaster (amendment) 1 46 Recorder of Deeds Adams County Girl Scout Council Inc. (Penn Laurel G. S. Council Inc.) E-51 956 Recorder of Deeds Adamstown Bicentennial Committee Inc. 4 322 Prothonotary Adamstown Bicentennial Committee Inc. -

The Last Post Reveille

TTHHEE LLAASSTT PPOOSSTT It being the full story of the Lancaster Military Heritage Group War Memorial Project: With a pictorial journey around the local War Memorials With the Presentation of the Books of Honour The D Day and VE 2005 Celebrations The involvement of local Primary School Chidren Commonwealth War Graves in our area Together with RREEVVEEIILLLLEE a Data Disc containing The contents of the 26 Books of Honour The thirty essays written by relatives Other Associated Material (Sold Separately) The Book cover was designed and produced by the pupils from Scotforth St Pauls Primary School, Lancaster working with their artist in residence Carolyn Walker. It was the backdrop to the school's contribution to the "Field of Crosses" project described in Chapter 7 of this book. The whole now forms a permanent Garden of Remembrance in the school playground. The theme of the artwork is: “Remembrance (the poppies), Faith (the Cross) and Hope( the sunlight)”. Published by The Lancaster Military Heritage Group First Published February 2006 Copyright: James Dennis © 2006 ISBN: 0-9551935-0-8 Paperback ISBN: 978-0-95511935-0-7 Paperback Extracts from this Book, and the associated Data Disc, may be copied providing the copies are for individual and personal use only. Religious organisations and Schools may copy and use the information within their own establishments. Otherwise all rights are reserved. No part of this publication and the associated data disc may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the Editor. -

Lancaster Castle: the Rebuilding of the County Gaol and Courts

Contrebis 2019 v37 LANCASTER CASTLE: THE REBUILDING OF THE COUNTY GAOL AND COURTS John Champness Abstract This paper details the building and rebuilding of Lancaster Castle in the late-eighteenth and early- nineteenth centuries to expand and improve the prison facilities there. Most of the present buildings in the Castle date from a major scheme of extending the County Gaol, undertaken in the last years of the eighteenth century. The principal architect was Thomas Harrison, who had come to Lancaster in 1782 after winning the competition to design Skerton Bridge (Champness 2005, 16). The scheme arose from concern about the unsatisfactory state of the Gaol which was largely unchanged from the medieval Castle (Figure 1). Figure 1. Plan of Lancaster Castle taken from Mackreth’s map of Lancaster, 1778 People had good reasons for their concern, because life in Georgian gaols was somewhat disorganised. The major reason lay in how the role of gaols had been expanded over the years in response to changing pressures. County gaols had originally been established in the Middle Ages to provide short-term accommodation for only two groups of people – those awaiting trial at the twice- yearly Assizes, and convicted criminals who were waiting for their sentences to be carried out, by hanging or transportation to an overseas colony. From the late-seventeenth century, these people were joined by debtors. These were men and women with cash-flow problems, who could avoid formal bankruptcy by forfeiting their freedom until their finances improved. During the mid- eighteenth century, numbers were further increased by the imprisonment of ‘felons’, that is, convicted criminals who had not been sentenced to death, but could not be punished in a local prison or transported. -

A History of Lancaster and District Male Voice Choir

A History of Lancaster and District Male Voice Choir From 1899 to 2013 this history is based on the writings of Roland Brooke and the first history contained in the original website (no longer operational). From 2013 it is the work of Dr Hugh Cutler sometime Chairman and subsequently Communications Officer and editor of the website. The Years 1899-1950 The only indication of the year of foundation is that 1899 is mentioned in an article in the Lancaster Guardian dated 13th November 1926 regarding the Golden Wedding Anniversary of Mr. & Mrs. R.T. Grosse. In this article it states that he was 'for many years the Conductor of the Lancaster Male Voice Choir which was formed at the end of 1899'. The Guardian in February 1904 reported that 'the Lancaster Male Voice Choir, a new organisation in the Borough, are to be congratulated on the success of their first public concert'. The content of the concert was extensive with many guest artistes including a well-known soprano at that time, Madame Sadler-Fogg. In the audience were many honoured guests, including Lord Ashton, Colonel Foster, and Sir Frederick Bridge. In his speech, the latter urged the Choir to 'persevere and stick together'. Records state that the Choir were 'at their zenith' in 1906! This first public concert became an annual event, at varying venues, and their Sixth Annual Concert was held in the Ashton Hall in what was then known as 'The New Town Hall' in Lancaster. This was the first-ever concert held in 'The New Town Hall', and what would R.T. -

Report and Accounts Year Ended 31St March 2019

Report and Accounts Year ended 31st March 2019 Preserving the past, investing for the future LLancaster Castle’s John O’Gaunt gate. annual report to 31st March 2019 Annual Report Report and accounts of the Duchy of Lancaster for the year ended 31 March 2019 Presented to Parliament pursuant to Section 2 of the Duchies of Lancaster and Cornwall (Accounts) Act 1838. annual report to 31st March 2019 Introduction Introduction History The Duchy of Lancaster is a private In 1265, King Henry III gifted to his estate in England and Wales second son Edmund (younger owned by Her Majesty The Queen brother of the future Edward I) as Duke of Lancaster. It has been the baronial lands of Simon de the personal estate of the reigning Montfort. A year later, he added Monarch since 1399 and is held the estate of Robert Ferrers, Earl separately from all other Crown of Derby and then the ‘honor, possessions. county, town and castle of Lancaster’, giving Edmund the new This ancient inheritance began title of Earl of Lancaster. over 750 years ago. Historically, Her Majesty The Queen, Duke of its growth was achieved via In 1267, Edmund also received Lancaster. legacy, alliance and forfeiture. In from his father the manor of more modern times, growth and Newcastle-under-Lyme in diversification have been delivered Staffordshire, together with lands through active asset management. and estates in both Yorkshire and Lancashire. This substantial Today, the estate covers 18,481 inheritance was further enhanced hectares of rural land divided into by Edmund’s mother, Eleanor of five Surveys: Cheshire, Lancashire, Provence, who bestowed on him Staffordshire, Southern and the manor of the Savoy in 1284. -

Goathland November 2017

Conservation Area Character Appraisal and Management Plan Goathland November 2017 2 Contents Summary 3 Introduction 8 Location and context 10 The History of Goathland 12 The ancient street plan, boundaries and open spaces 24 Archaeology 29 Vistas and views 29 The historic buildings of Goathland 33 The little details 44 Character Areas: 47 St. Mary's 47 Infills and Intakes 53 Victorian and Edwardian Village 58 NER Railway and Mill 64 Recommendations for future management 72 Conclusion 82 Bibliography and Acknowledgements 83 Conservation Area Appraisal and Management Plan for Goathland Conservation Area 2 3 Summary of Significance Goathland is a village of moorland views and grassy open spaces of untamed pasture and boggy verges crossed by ancient stone trods and tracks. These open spaces once separated the dispersed farms that spread between the first village nucleus around the church originally founded in the 12th century, the village pound nearby, and, a grouping of three farms and the mill to the north east, located by the river and known to exist by the early 13th century. This dispersed agricultural settlement pattern started to change in the 1860s as more intakes were filled with villas and bungalows, constructed by the Victorian middle classes arriving by train and keen to visit or stay and admire the moorland views and waterfalls. This created a new village core closer to the station where hotels and shops were developed to serve visitors and residents and this, combined with the later war memorial, has created a village green character and a tighter settlement pattern than seen elsewhere in the village. -

Grouse in the Royal Purple the King of Gamebirds Is Undergoing a Renaissance on Moorland Leased from the Duchy of Lancaster

Grouse in the royal purple The king of gamebirds is undergoing a renaissance on moorland leased from the Duchy of Lancaster. Jonathan Young enjoys the spoils. Photographs by Ann Curtis t would by dismissed by modern art light planes and squadrons of Range Rovers that spaciousness seems almost as impos- critics as Victorian whimsy, but it’s hurtle northwards, ferrying guns from city to sible as boarding the London train with guns, hard to find a sportsman who doesn’t moor, but then the leisured classes truly setters and clad in full tweeds. Yet, for one brief adore George Earl’s Going north, King’s deserved their adjective; and that comfortable moment last season, a century disappeared Cross station, painted in 1893. It depicts position lasted well into the 20th century. Eric into a golden past, thanks to Her Majesty, the Ia sporting party waiting to board the 10 Parker, an Editor of the Field, could still put Duchy of Lancaster and Andrew Pindar. o’clock north, the platform crowded with this poser to readers in 1918; five invitations A party of guns, 12-bores in slips, gundogs gentlemen, ladies and their servants. Minor arrive simultaneously in the post – which in tow, strolled down the high street of mountains of cane rods and gaffs, creels and would they choose: three days’ partridge driv- Pickering, North Yorkshire. Heads were oak-and-leather gun cases are guarded care- ing; a week’s grouse-driving; 10 days on the slightly muzzy after a dinner verging on a fully by the keepers while they control their sea coast of the west of Scotland; a fortnight in banquet at the White Swan Inn. -

The First World War

OTHER PLACES OF INTEREST Lancaster & Event Highlights NOW AND THEN – LINKING PAST WITH THE PRESENT… Westfield War Memorial Village The First The son of the local architect, Thomas Mawson, was killed in April Morecambe District 1915 with the King’s Own. The Storey family who provided the land of World War Sat Jun 21 – Sat Oct 18 Mon Aug 4 Wed Sep 3 Sat Nov 8 the Westfield Estate and with much local fundraising the village was First World War Centenary War! 1914 – Lancaster and the Kings Own 1pm - 2pm Origins of the Great War All day ‘Britons at War 1914 – 1918’ 7:30pm - 10pm Lancaster and established in the 1920s and continued to be expanded providing go to War, Exhibition Lunchtime Talk by Paul G.Smith District Male Voice Choir Why remember? Where: Lancaster City Museum, Market Where: Lancaster City Museum, Where: Barton Road Community Centre, Where: The Chapel, University accommodation for soldiers and their families. The village has it’s Square, Lancaster Market Square, Lancaster Barton Road, Bowerham, Lancaster. of Cumbria, Lancaster own memorial, designed by Jennifer Delahunt, the art mistress at Tel: 01524 64637 T: 01524 64637 Tel: 01524 751504 Tel: 01524 582396 EVENTS, ACTIVITIES AND TRAIL GUIDE the Storey Institute, which shows one soldier providing a wounded In August 2014 the world will mark the one hundredth Sat Jun 28 Mon Aug 4 Sat Sep 6 Sun Nov 9 soldier with a drink, not the typical heroic memorial one usually anniversary of the outbreak of the First World War. All day Meet the First World War Soldier 7pm - 9pm “Your Remembrances” Talk All day Centenary of the Church Parade of 11am Remembrance Sunday But why should we remember? Character at the City Museum Where: Meeting Room, King’s Own Royal the ‘Lancaster Pals’ of the 5th Battalion, Where: Garden of Remembrance, finds. -

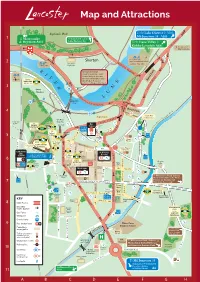

Map and Attractions

Map and Attractions 1 & Heysham to Lancaster City Park & Ride to Crook O’Lune, 2 Skerton t River Lune Millennium Park and Lune Aqueduct Bulk Stree N.B. Greyhound Bridge closed for works Jan - Sept. Skerton Bridge to become two-way. Other trac routes also aected. Please see Retail Park www.lancashire.gov.uk for details 3 Quay Meadow re Ay en re e Park G kat S 4 Retail Park Superstore Vicarage Field Buses & Taxis . only D R Escape H T Room R NO Long 5 Stay Buses & Taxis only Cinema LANCASTER VISITOR Long 6 INFORMATION CENTRE Stay e Gregson Th rket Street Centre Storey Ma Bashful Alley Sir Simons Arcade Long 7 Stay Long Stay Buses & Taxis only Magistrates 8 Court Long Stay 9 /Stop l Cruise Cana BMI Hospital University 10 Hospital of Cumbria visitors 11 AB CDEFG H ATTRACTIONS IN AND Assembly Rooms Lancaster Leisure Park Peter Wade Guided Walks AROUND LANCASTER Built in 1759, the emporium houses Wyresdale Road, Lancaster, LA1 3LA A series of interesting themed walks an eclectic mix of stalls. 01524 68444 around the district. Lancaster Castle lancasterleisurepark.com King Street, Lancaster, LA1 1LG 01524 420905 Take a guided tour and step into a 01524 414251 - GB Antiques Centre visitlancaster.org.uk/whats-on/guided- thousand years of history. lancaster.gov.uk/assemblyrooms Open 10:00 – 17:00 walks-with-peter-wade/ Adults £1.50, Children/OAP 75p, Castle Park, Lancaster, LA1 1YJ Tuesday–Saturday 10:00 - 16:30 Under 5s Free Various dates, start time 2pm. 01524 64998 Closed all Bank Holidays Trade Dealers Free Tickets £3 lancastercastle.com - Lancaster Brewery Castle Grounds open 09:30 – 17:00 daily King Street Studios Monday-Thursday 10:00 - 17:00 Lune Aqueduct Open for guided tours 10:00 – 16:00 Exhibition space and gallery showing art Friday- Sunday 10:00 – 18:00 Take a Lancaster Canal Boat Cruise (some restrictions, please check with modern and contemporary values. -

JL-Friends-Newsletter-August-2020

1 LANCASTER JUDGES’ LODGINGS UPDATE Newsletter of the Friends of Lancaster Judges’ Lodgings Issue no 44 August 2020 The Judges’ Lodgings in August The final decision for the Judges’ Lodgings to reopen for Bank Holiday weekend was made at the beginning of the month, so although work had been going on to make the JL ready in itself, as well as covering all the Covid-secure requirements, the pace of activity quickened somewhat now that an actual date had been set. Staff had to be brought back into the JL as a team, volunteers confirmed, rotas set, new training provided, final tidy up of garden, collection cleaning – a flurry of excitement tinged with apprehension, with a new normal looming ahead so very different from the old. By opening day, Friday 28 August, all was ready (at least unready bits didn’t show), the doors were opened wide and the new glass porch was revealed on the way into the entrance hall. The porch has doors opening either to the right or the left, so was immediately the start of the one- way system round the building. Discreet Covid-secure signs were in place, guiding the flow, regulating distances and offering hand sanitisation stations. Even the display furniture was brought into use. Staff are wearing visors, visitors must wear face coverings, but none of it detracts from the charm of the JL itself. Once through reception in the main hall the way led to and through the brand new Welcome Gallery. A Charitable Incorporated Organisation Charity number 1171209 2 The Welcome Gallery This is an exciting initiative, now installed in what used to be the ticket and shop area. -

Post-Medieval Colonisation in the Forests of Howland, Knaresborough and Pickering

THE UNIVERSITY OF HULL POST-MEDIEVAL COLONISATION IN THE FORESTS OF HOWLAND, KNARESBOROUGH AND PICKERING being a Thesis submitted for the Degree of Ph.D. in the University of Hull by MAURICE TURNER, B.Sc., B.A., OCTOBER, 1987 POST-MEDIEVAL COLONISATION IN THE FORESTS OF BOWLAND, KNARESBOROUGH AND PICKERING Contents Preface Chapter I The material of the thesis and the methods of Page 1 investigation Chapter II The medieval background to encroachment Page 7 a) The utilisation of forest land b) The nature of medieval clearance c) Early clearances in the Forest of Pickering d) Medieval colonisation in Bowland Forest e) Migration into Knaresborough Forest after the Black Death f) The medieval settlement pattern in Knaresborough Forest g) Measures of forest land Chapter III Tenures, Rents and Taxes in the Tudor Forests Page 36 a) The evidence of the Tudor Lay Subsidies b) The evidence of manorial rent rolls C) Tudor encroachment on the common wastes Chapter IV The demographic experience of forest Page 53 parishes Chapter V The reasons for encroachment Page 73 a) The problem of poverty in 17th century England b) The evidence for subdivision of holdings c) Changes in the size of tenements with time d) Subdivided holdings in Forests other than Knaresborough Chapter VI Illegal encroachment in the Forest of Knaresborough Page 96 a) The creation of new hamlets 1600 - 1669 b) The slowing down of encroachment in the late 17th century c) The physical form of squatter encroachments as compared to copyholder intakes before 1730 Chapter VII Alternative -

Early Stages of the Quaker

LA N CA s E N O N CON EOR M T T Y TH E EJECTED OF 1 66 2 I N C U M BER LA N D AN D WESTM ORLAN D H ISTOR Y O F I N DE P EN DENC Y I N TOC K HOLES TH E STOR Y O F TH E LANCASH I R E CON GRE GAT IONA L U N I ON TH E SER M ON ON TH E M OU NT I N R ELAT T ON T o THE P RESENT WA R CON SC I ENCE AN D THE WA R FRO M TH E GREAT AWA KE N T NG T o THE E V AN GELICAL R EV I V AL FI DELITY TO AN I DEAL CON G R EGATIONALIS M R E -E XAM IN ED I C A M BR E H E R E L l Gl O U S M Y TIC SAA OS , T S THO M AS j OLu E O F ALTH A M AN D WYM ON D HOU SES THE H ERox c A GE O F CON G RE GATIONA LISM EA R L Y ST A GE S O F T H Q UA K E R M O V E M EN T IN L A N CA SH IR E BB BB B R B M A . E . A D. V . m . NIGHTIN G LE , , CONGR EGAT I P R E FA CE A FEW years ago while engaged in s ome hist orical research or m r andPWestmorland r m w k in Cu be land , elating ainly t o 1 r m o o the 7th centu y , I ca e much int c ntact with the r mo of r o Not Quake vement that pe i d .