The Life and Work of Michael Sendivogius (1566-1636)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alchemical Culture and Poetry in Early Modern England

Alchemical culture and poetry in early modern England PHILIP BALL Nature, 4–6 Crinan Street, London N1 9XW, UK There is a longstanding tradition of using alchemical imagery in poetry. It first flourished at the end of the sixteenth century, when the status of alchemy itself was revitalised in European society. Here I explain the reasons for this resurgence of the Hermetic arts, and explore how it was manifested in English culture and in particular in the literary and poetic works of the time. In 1652 the English scholar Elias Ashmole published a collection of alchemical texts called Theatrum Chymicum Britannicum, comprising ‘Several Poeticall Pieces of Our Most Famous English Philosophers’. Among the ‘chemical philosophers’ represented in the volume were the fifteenth-century alchemists Sir George Ripley and Thomas Norton – savants who, Ashmole complained, were renowned on the European continent but unduly neglected in their native country. Ashmole trained in law, but through his (second) marriage to a rich widow twenty years his senior he acquired the private means to indulge at his leisure a scholarly passion for alchemy and astrology. A Royalist by inclination, he had been forced to leave his London home during the English Civil War and had taken refuge in Oxford, the stronghold of Charles I’s forces. In 1677 he donated his impressive collection of antiquities to the University of Oxford, and the building constructed to house them became the Ashmolean, the first public museum in England. Ashmole returned to London after the civil war and began to compile the Theatrum, which was intended initially as a two-volume work. -

Muslim Scientists and Thinkers

MUSLIM SCIENTISTS AND THINKERS Syed Aslam Second edition 2010 Copyright 2010 by Syed Aslam Publisher The Muslim Observer 29004 W. Eight Mile Road Farmington, MI 48336 Cover Statue of Ibn Rushd Cordoba, Spain ISBN 978-1-61584-980-2 Printed in India Lok-Hit Offset Shah-e-Alam Ahmedabad Gujarat ii Dedicated to Ibn Rushd and other Scientists and Thinkers of the Islamic Golden Age iii CONTENTS Acknowledgments ................................................VI Foreword .............................................................VII Introduction ..........................................................1 1 Concept of Knowledge in Islam ............................8 2 Abu Musa Jabir Ibn Hayyan..................................25 3 Al-Jahiz abu Uthman Ibn Bahar ...........................31 4 Muhammad Ibn Musa al-Khwarizmi....................35 5 Abu Yaqoub Ibn Ishaq al-Kindi ............................40 6 Muhammad bin Zakaria Razi ...............................45 7 Jabir ibn Sinan al-Batani.......................................51 8 Abu Nasar Mohammad ibn al-Farabi....................55 9 Abu Wafa ibn Ismail al-Buzjani ...........................61 10 Abu Ali al-Hasan ibn al-Haytham .......................66 11 Abu Rayhan ibn al-Biruni ....................................71 12 Ali al-Hussain ibn Sina ........................................77 13 Abu Qasim ibn al-Zahrawi ..................................83 iv 14 Omar Khayyam ...................................................88 15 Abu Hamid al-Ghazali .........................................93 -

Alchemy Ancient and Modern

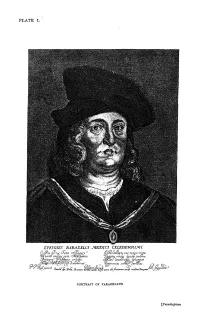

PLATE I. EFFIGIES HlPJ^SELCr JWEDlCI PORTRAIT OF PARACELSUS [Frontispiece ALCHEMY : ANCIENT AND MODERN BEING A BRIEF ACCOUNT OF THE ALCHEMISTIC DOC- TRINES, AND THEIR RELATIONS, TO MYSTICISM ON THE ONE HAND, AND TO RECENT DISCOVERIES IN HAND TOGETHER PHYSICAL SCIENCE ON THE OTHER ; WITH SOME PARTICULARS REGARDING THE LIVES AND TEACHINGS OF THE MOST NOTED ALCHEMISTS BY H. STANLEY REDGROVE, B.Sc. (Lond.), F.C.S. AUTHOR OF "ON THE CALCULATION OF THERMO-CHEMICAL CONSTANTS," " MATTER, SPIRIT AND THE COSMOS," ETC, WITH 16 FULL-PAGE ILLUSTRATIONS SECOND AND REVISED EDITION LONDON WILLIAM RIDER & SON, LTD. 8 PATERNOSTER ROW, E.G. 4 1922 First published . IQH Second Edition . , . 1922 PREFACE TO THE SECOND EDITION IT is exceedingly gratifying to me that a second edition of this book should be called for. But still more welcome is the change in the attitude of the educated world towards the old-time alchemists and their theories which has taken place during the past few years. The theory of the origin of Alchemy put forward in I has led to considerable discussion but Chapter ; whilst this theory has met with general acceptance, some of its earlier critics took it as implying far more than is actually the case* As a result of further research my conviction of its truth has become more fully confirmed, and in my recent work entitled " Bygone Beliefs (Rider, 1920), under the title of The Quest of the Philosophers Stone," I have found it possible to adduce further evidence in this connec tion. At the same time, whilst I became increasingly convinced that the main alchemistic hypotheses were drawn from the domain of mystical theology and applied to physics and chemistry by way of analogy, it also became evident to me that the crude physiology of bygone ages and remnants of the old phallic faith formed a further and subsidiary source of alchemistic theory. -

A Short Course in Forgetting Chemistry

[This is from What Painting Is (New York: Routledge, 1998). This was originally posted on www.jameselkins.com. This version is unillustrated: some illustrations are on the website. Some alchemical symbols have dropped out of this file. See the website for context, other material from the book, and for contact information for the author. (September 2009).] 1 A short course in forgetting chemistry Painting is alchemy. Its materials are worked without knowledge of their properties, by blind experiment, by the feel of the paint. A painter knows what to do by the tug of the brush as it pulls through a mixture of oils, and by the look of colored slurries on the palette. Drawing is a matter of touch: the pressure of the charcoal on the slightly yielding paper, the sticky slip of the oil crayon between the fingers. Artists become expert in distinguishing between degrees of gloss and wetness—and they do so without knowing how they do it, or how chemicals create their effects. Monet’s paintings are a case in point. They seem especially simple to many people, as if Monet were the master of certain moods—of moist bluish twilight or candent yellow beaches— but nothing more: as if he had no sense that painting could be anything but a method for fixing light onto canvas. In his singleminded pursuit of the grain and feel of light, he seems to forget who he is, and who he is painting. He has only a weak attachment to people, and he treats the figures who stray into his pictures as if they were colored dolls instead of friends and relatives.i Instead his attention is riveted to the blurry shapes that come forward through the imperfect atmosphere, and on the shifting tints of light that somehow congeal into meadows and oceans and haystacks. -

Remarks Upon Alchemy and the Alchemists

Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2010 with funding from Research Library, The Getty Research Institute http://www.archive.org/details/remarksuponalcheOOhitc NEW THOUGTIT LIBRARY ASSOCIATION' No. REMARKS ALCHEMY AND THE ALCHEMISTS, INDICATIXG A METHOD OF DISCOVEKI^'G THE TEUE NATURE OF HERMETIC PHILOSOPHY; A^D SHOWING THAT THE SEARCH AFTER HAD NOT FOR ITS OBJECT THE DISCOVERY OF AN AGENT FOR THE TRANSMUTATION OF METALS. BEING ALSO AS ATTEMPT TO RESCUE FROM UNDESERVED OPPROBRIUM THE REPUTATION OF A CLASS OF EXTEAORDIXARY THINKEES IN PAST AGES. ' Man shall not live by bread alone." BOSTON: CROSBY, NICHOLS, AND COMPANY, 111 Washington Street. 1857. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1857, by Crosby, Nichols, and Company, in the Clerk's Office of the District Court of the District of Massachusetts. cambsidge: metcalf and company, printers to the tjnrversitt. NE¥/ THOUGHT LIBRARY ASSOCIATION No. PEEFACE. ED.W. PARKER, L ittle Ruc k, Ark. It may seem superfluous in the author of the fol- lowing remarks to disclaim the purpose of re vivino- the study of Alchemy, or the method of teaching adopted by the Alchemists. Alchemical works stand related to moral and intellectual geography, some- what as the skeletons of ichthyosauri and plesio- sauri are related to geology. They are skeletons of thought in past ages. It is chiefly from this point of view that the writer of the following pages submits his opinions upon Alchemy to the public. He is convinced that the character of the Alchemists, and the object of their study, have been almost universally misconceived ; and as a matter of fact^ though of the past, he thinks it of sufficient importance to take a step in the right direction for developing the true nature of the studies of that extraordinary class of thinkers. -

Alchemy Archive Reference

Alchemy Archive Reference 080 (MARC-21) 001 856 245 100 264a 264b 264c 337 008 520 561 037/541 500 700 506 506/357 005 082/084 521/526 (RDA) 2.3.2 19.2 2.8.2 2.8.4 2.8.6 3.19.2 6.11 7.10 5.6.1 22.3/5.6.2 4.3 7.3 5.4 5.4 4.5 Ownership and Date of Alternative Target UDC Nr Filename Title Author Place Publisher Date File Lang. Summary of the content Custodial Source Rev. Description Note Contributor Access Notes on Access Entry UDC-IG Audience History 000 SCIENCE AND KNOWLEDGE. ORGANIZATION. INFORMATION. DOCUMENTATION. LIBRARIANSHIP. INSTITUTIONS. PUBLICATIONS 000.000 Prolegomena. Fundamentals of knowledge and culture. Propaedeutics 001.000 Science and knowledge in general. Organization of intellectual work 001.100 Concepts of science Alchemyand knowledge 001.101 Knowledge 001.102 Information 001102000_UniversalDecimalClassification1961 Universal Decimal Classification 1961 pdf en A complete outline of the Universal Decimal Classification 1961, third edition 1 This third edition of the UDC is the last version (as far as I know) that still includes alchemy in Moreh 2018-06-04 R 1961 its index. It is a useful reference documents when it comes to the folder structure of the 001102000_UniversalDecimalClassification2017 Universal Decimal Classification 2017 pdf en The English version of the UDC Online is a complete standard edition of the scheme on the Web http://www.udcc.org 1 ThisArchive. is not an official document but something that was compiled from the UDC online. Moreh 2018-06-04 R 2017 with over 70,000 classes extended with more than 11,000 records of historical UDC data (cancelled numbers). -

Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity Sourcebook, 2013-2014 This Sourcebook Is the Property Of

Alpha Chi Sigma Sourcebook A Repository of Fraternity Knowledge for Reference and Education Academic Year 2013-2014 Edition 1 l Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity Sourcebook, 2013-2014 This Sourcebook is the property of: ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Full Name Chapter Name ___________________________________________________ Pledge Class ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Date of Pledge Ceremony Date of Initiation ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Master Alchemist Vice Master Alchemist ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Master of Ceremonies Reporter ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Recorder Treasurer ___________________________________________________ ___________________________________________________ Alumni Secretary Other Officer Members of My Pledge Class ©2013 Alpha Chi Sigma Fraternity 6296 Rucker Road, Suite B | Indianapolis, IN 46220 | (800) ALCHEMY | [email protected] | www.alphachisigma.org Click on the blue underlined terms to link to supplemental content. A printed version of the Sourcebook is available from the National Office. This document may be copied and distributed freely for not-for-profit purposes, in print or electronically, provided it is not edited or altered in any -

What Painting Is “A Truly Original Book

More praise for What Painting Is “A truly original book. It will make you look at paintings differently and think about paint differently.”—Boston Globe “ This is a novel way of considering paintings, and excitingly different from standard art criticism.”—Atlantic Monthly “The best books often introduce new worlds. What Painting Is exposes the reader to painting materials, brushstroke techniques, and alchemy of all things, in a book filled with rich descriptions and illuminating insight. Read this and you’ll never look at paintings in the same way again.”— Columbus Dispatch “ James Elkins, his academic laces untied, traces a mysterious, evocation and an utterly convincing parallel between two spirits grounded in the earth—alchemy and painting. The author is an alchemist of ideas, and a painter. His openness to the love of quicksilver and sulfur, to putrefying animal excretions, and his expertise in imprimaturas, his feeling for the mysteries of the brushstroke —all of these allow him to concoct a heady elixir.” —Roald Hoffmann, Winner of the Noble Prize in Chemistry, 1981 What Painting Is How to Think about Oil Painting, Using the Language of Alchemy James Elkins Routledge New York • London Published in 2000 by Routledge 29 West 35th Street New York, NY 10001 This edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2005. “To purchase your own copy of this or any of Taylor & Francis or Routledge’s collection of thousands of eBooks please go to www.eBookstore.tandf.co.uk.” Published in Great Britain by Routledge 11 New Fetter Lane London EC4P 4EE Copyright © 1999 by Routledge All rights reserved. -

The Hermetic Journal Is One Year Old from the Date of Its Inception

A Collection oJSacredl\.fayicl;.Com 4 he Esoteric ~ibrary ERMETIC JOURNAL I &kE EEUmIC JO~X~AL.is published . quarterly 12 Antigua Street Ein'mgh 1 Edited by Adam NcLean I ,All material copyright the individ- ual contributors. Material not cred- ited, copyright the iiermetic Journal. ISSN 0141-6391 b J Editorial Editorial News and Information The Zodiac and the is en enthusiast for the rebirth of Flashing Colours tho hermetic tradition, I feel I Ithell Colquhoun Q mst speak out against the current Colour and the Two Sigils "Necronomicon Phenomenon". Ithell Colquhoun @ In the last year or so a number of A ~osicrucian/Alchemical writere and publishers have intrigued I4ystery Centre in Scotland to fabricate versions of a suppoeed Adam McLean Q occult manuscript, an ancient grip oire called the Necronomiwn. These Hermetic Bleditation No 4 recreatians of a supposed lhgical Regular Feature test are not arrived at by medim Number and Space ship, automatic writing, or some Patricia Villiers-Stuart@ kind of 'received coenunicationl, which might make them worthy of some Alchemical l-Iandala No 4 attention, but arise purely out of Regular Feature conscious contrivance. The Golden Chain of Homer The source of the name Necronomiwn, Commentary by Adam XcLeanO is the writer H.P. Lovecraft, who Final No of a series of 4 seems to have been a soul oyen to The Fountain Allegory of obsessive encounters with the dark Bernard of Treviso unconscious facct of the lower astral world, rather than a balanced Fulovlelli occultism. Lovecraft oan only per Kenneth Rzyner Johnson @ petuate the image of the frightening The Rosicrucian Cz.nons nature of the meeting with the of Benedict Hilirrion occult aide of life, rather than the positive inspirational espeot which The Four Fire Festivals I trust all the readers of this Part Three - Seltane magazine find in the esoteric. -

Splendor Solis.Pdf

SPLENDOR SOLIS A.D. 1582. SPLENDOR SOLIS ALCHEMICAL TREATISES OF SOLOMON TRISMOSIN ADEPT AND TEACHER OF PARACELSUS Including 22 Allegorical Pictures Reproduced from the Original Paintings in the Unique Manuscript on Vellum, dated 1582, in the British Museum. With Introduction, Elucidation of the Paintings, aiding the Interpretation of their Occult meaning, Trismosin's Auto- biographical Account of his Travels in Search of the Philoso- pher's Stone, A SUMMARY OF HIS ALCHEMICAL PROCESS CALLED " THE RED LION," and EXPLANATORY NOTES BY J. K. LONDON: KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO., LTD., BROADWAY HOUSE, 68-74 CARTER LANE, E.O. 4. To THE ETERNAL MEMORY OF JOSEPH WALLACE MYSTIC, HEALER, AND REVEALER OF OCCULT TRUTH. MY REVERED TEACHER AND FRIEND I DEDICATE THIS BOOK IN WHICH HE WAS DEEPLY INTERESTED J.K. INTRODUCTORY. HEN in the period of the Renaissance, men's m i n d s W were waking from the long sleep of mediaeval darkness, SOLOMON TRISMOSIN, one of the less known Adepts of Alchemy, went forth in search of that secret knowledge, the possession of which leads to Alchemical Adeptship. His romantic Wanderings in Quest of the Philosopher's Stone, he has himself described, and if he declares to have reached that Eldorado of Hermetic Knowledge wherein is found the prized Philosopher's Stone, although we may feel inclined to doubt his word, we are, nevertheless not in a position to entirely dispute his statement. For since the discovery of radioactive substances chemical theory has vastly changed. The very Elementality of the chemical Elements is questioned, and the alchemical idea, that Metals can be decomposed into three ultimate principles : SALT, MERCURY, and SULPHUR, may not be so absurd after all. -

Alchemical Discourses on Nature and Creation in the Blazing World (1666)

NTU Studies in Language and Literature 57 Number 22 (Dec 2009), 57-76 Contemplation on the “World of My Own Creating”: Alchemical Discourses on Nature and Creation in The Blazing World (1666) Tien-yi Chao Assistant Professor, Department of Foreign Languages and Literatures National Taiwan University ABSTRACT This paper examines Margaret Cavendish’s The Blazing World from an alchemical perspective, with special references to passages regarding the perception of the cosmos and the creation of immaterial worlds. Even though the text is not the first work addressing the Utopian theme, it is innovative in utilising alchemical allegories to present both the author’s philosophical thoughts and the process of creative writing. In order to explore the complexity, versatility and richness of The Blazing World, my reading focuses on the Empress’s discourses on nature and the narrative surrounding her creation of worlds, while at the same time draws from early modern alchemical texts, particularly the treatises by Paracelsus and Michael Sendivogius. I argue that it is necessary for modern readers to revisit the esoteric and mystical nature of alchemical imagery, in order to develop a more profound understanding of the ways in which the Duchess of Newcastle created and refined her various imaginative worlds. Keywords : alchemy, Paracelsus, Michael Sendivogius, The One, creation, Margaret Cavendish, fiction, Utopian literature. 58 NTU Studies in Language and Literature 以煉金術觀點解讀《炫麗新世界》當中的 自然觀與創世情節 趙恬儀 國立台灣大學外國語文學系助理教授 摘 要 本論文試圖從西方煉金術的角度,解讀瑪格麗特•柯芬蒂詩的奇想故事《炫 -

Esoterismo Y Esoteristas En La Modernidad Temprana Europeo-Occidental”

UNIVERSIDAD DE BUENOS AIRES FACULTAD DE FILOSOFIA Y LETRAS DEPARTAMENTO DE HISTORIA SEMINARIO DE INVESTIGACION Profesor: Dr. Juan Pablo Bubello 2º cuatrimestre 2013. Programa nº: “Esoterismo y esoteristas en la modernidad temprana europeo-occidental” Fundamentación-Objetivos. Como no podría ser de otra forma en el campo de las humanidades, los especialistas en la historia del esoterismo occidental mantienen entre sí arduas discusiones. Sin embargo, también coinciden en que, entre fines del siglo XV y mediados del XVII, la magia natural, la tradición hermética, la cábala cristiana, la magia astral, la astrología, la alquimia y la alquimia rosacruz se articularon de tal forma en Europa Occidental que conformaron las principales corrientes del esoterismo del período, promoviéndose entonces el desarrollo de un entramado de prácticas y representaciones heterogéneas pero específicas. Los principales agentes culturales que caracterizaron al esoterismo de la modernidad temprana europeo-occidental fueron (entre otros): Marsilio Ficino, Giovanni Pico della Mirándola, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa, Guillaume Postel, Paracelso, John Dee, Giordano Bruno, Tommaso Campanella, Johann Andreas, Michael Maier, Robert Fludd y Thomas Vaughan. El presente seminario de investigación propone entonces, desde el enfoque histórico-cultural, el abordaje de uno de los problemas historiográficos centrales de la Europa Moderna, articulando el análisis del esoterismo con los diversos problemas históricos de la época que le conciernen y en el cual estos esoteristas se encuentran