A Post-Colonial Analysis of Shakespeare's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The History of the Jamestown Colony: Seventeenth-Century and Modern Interpretations

The History of the Jamestown Colony: Seventeenth-Century and Modern Interpretations A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation with research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of the Ohio State University By Sarah McBee The Ohio State University at Mansfield June 2009 Project Advisor: Professor Heather Tanner, Department of History Introduction Reevaluating Jamestown On an unexceptional day in December about four hundred years ago, three small ships embarked from an English dock and began the long and treacherous voyage across the Atlantic. The passengers on board envisioned their goals – wealth and discovery, glory and destiny. The promise of a new life hung tantalizingly ahead of them. When they arrived in their new world in May of the next year, they did not know that they were to begin the journey of a nation that would eventually become the United States of America. This summary sounds almost ridiculously idealistic – dream-driven achievers setting out to start over and build for themselves a better world. To the average American citizen, this story appears to be the classic description of the Pilgrims coming to the new world in 1620 seeking religious freedom. But what would the same average American citizen say to the fact that this deceptively idealistic story actually took place almost fourteen years earlier at Jamestown, Virginia? The unfortunate truth is that most people do not know the story of the Jamestown colony, established in 1607.1 Even when people have heard of Jamestown, often it is with a negative connotation. Common knowledge marginally recognizes Jamestown as the colony that predates the Separatists in New England by more than a dozen years, and as the first permanent English settlement in America. -

Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1991 "In the Hollow Lotus-Land": Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623 Matthew R. Laird College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Laird, Matthew R., ""In the Hollow Lotus-Land": Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623" (1991). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625691. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-dbem-8k64 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •'IN THE HOLLOW LOTOS-LAND": DISCORD, ORDER, AND THE EMERGENCE OF STABILITY IN EARLY BERMUDA, 1609-1623 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Matthew R. Laird 1991 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Matthew R. Laird Approved, July 1991 -Acmy James Axtell Thaddeus W. Tate TABLE OP CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................... iv ABSTRACT...............................................v HARBINGERS....... ,.................................... 2 CHAPTER I. MUTINY AND STARVATION, 1609-1615............. 11 CHAPTER II. ORDER IMPOSED, 1615-1619................... 39 CHAPTER III. THE FOUNDATIONS OF STABILITY, 1619-1623......60 A PATTERN EMERGES.................................... -

ISC Program 16 Web Version+One

RICHARD GRIFFITH PARK FREE SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL JUNE 25 - SEPT 4 the TEMPEST INDEPENDENT SHAKESPEARE CO. SHAKESPEARE SET FREE INDEPENDENT SHAKESPEARE CO. / GRIFFITH PARK FREE SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL Recently, a long time audience member, Frank Lopes, shared a celebrates Shakespeare’s stories and language, the natural beauty sonnet that he wrote about a tree. of the park, and the communion between the audience and the players that takes place night after night. It’s a lovely tree--in fact, you can see it right now, from where you It is a gift to create theater for the Los Angeles community, and our are sitting. If you’re looking towards the Festival stage, it’ s just to efforts are reciprocated tenfold. You really are the engine that pow- the left. Before a performance, you’ll often find actors and audi- ers the Festival. Your financial donations keep the Festival running. ence members sitting under it, enjoying the shade: Your generosity of spirit when we meet you after performances (or Into the sky towards providence do reach onstage at intermission) is deeply moving. We love taking pictures The wise and solemn bows of mighty tree. with you, chatting with you season after season--and in some And when night’s air of summer words do breech, cases, watching you grow up! Those magic words of past set people free. Oh,Tree! What beauty hast thou witnessed here? Every so often a pizza is delivered to us backstage, or a plate of Of lives, of loves, of kingdoms lost to dust, cookies, or a bottle of champagne. -

Shakespeare Uncovered Viewing Guide

© 2013 WNET. All rights reserved. Teaching Colleagues, Shakespeare Uncovered, a six-part series airing on PBS beginning on January 25 th , is a teacher’s dream come true. Each episode gives us something that we teachers almost never get: a compelling, lively, totally accessible journey through and around a Shakespeare play, guided by brilliant and plain-spoken experts--all within one hour. I’m not given to endorsements, but oh, I love this series. Why will we teachers love it and why do we need it? • Because, as we learned from the very start of the Folger Library’s Teaching Shakespeare Institute, teachers tend to be more confident, better teachers if they have greater and deeper knowledge of the plays themselves. • Because no matter what our relationship with the plays – we love them, we struggle with them, we’re tired of teaching the same ones, we’re afraid of some of them – we almost never have the time to learn more about them. We are teachers, after all: always under a deadline, we’re reading, grading, prepping, mindful of the next deadline. (And then there’s the rest of our lives . ) Shakespeare Uncovered is your chance to take a deep, pleasurable dive into a handful of plays—ones you know well, others that may be less familiar to you. In six episodes, Shakespeare Uncovered takes on eight plays: Macbeth, Hamlet, The Tempest, Richard II, Twelfth Night and As You Like It, Henry IV, Part I, and Henry V . The host of each episode has plenty of Shakespeare cred--Ethan Hawke, Jeremy Irons, Joely Richardson and her mom, Vanessa Redgrave, for example--but each wants to learn more about the play. -

Tempest Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TEMPEST PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mercedes Lackey | 394 pages | 06 Dec 2016 | DAW BOOKS | 9780756409036 | English | United States Tempest PDF Book Restoration: Studies in English Literary Culture, — The chastity of the bride is considered essential and greatly valued in royal lineages. Pure singleplayer Want to be a lone sea wolf? HeroCraft PC. Sign In Sign in to add your own tags to this product. National Council of Teachers of English. In , Derek Jarman produced the homoerotic film The Tempest that used Shakespeare's language, but was most notable for its deviations from Shakespeare. The Tempest was one of the staples of the repertoire of Romantic Era theatres. Ariel was—with two exceptions—played by a woman, and invariably by a graceful dancer and superb singer. Tempest is for anyone who is done with alcohol or wants to be done with alcohol, for anyone who wants to change how they see themselves and their possibilities in life. Without these features the characters of the new fonts are similar each other. Pick a Plan Choose the level of support you need from our three membership options. Pirate cooperation Share the world of Tempest between you and your friends. This article is about the Shakespeare play. Shakespeare remakes. Upon the restoration of the monarchy in , two patent companies —the King's Company and the Duke's Company —were established, and the existing theatrical repertoire divided between them. Gonzalo's description of his ideal society 2. At least two other silent versions, one from by Edwin Thanhouser , are known to have existed, but have been lost. -

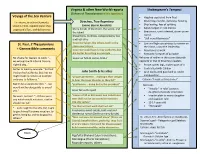

Theme Source Flow

Virginia & other New World reports Shakespeare’s Tempest (Echoes of Thessalonians in this typeface) Voyage of the Sea Venture • Flagship separated from fleet • Deafening thunder, darkness; howling Hurricane, wreck on Bermuda, • Ship leaking, fear of splitting social turmoil, capable leadership, • Safely lodged in rock crevice organized effort, and deliverance • Beauteous, spirit-infested, storm-prone island • “Still-vexed Bermudas” St. Paul, 2 Thessalonians Governor labors like others, both in the • Low and high conspiracies to remain on storm and ashore the island, usurp the leadership + Geneva Bible comments Governor could have led by authority, but • Resistance to work did better by setting an example • Romantic fantasies of paradise No shame for leaders to work: “… Behavior of nobles in the storm blatantly we wrought with labor & travaile opposite to that of Strachey’s leaders night & day…” • Prince carries logs, makes sport of it Better to lead by example: “Not but • Contrasted with Caliban that we had authority, but that we John Smith & his allies • Ariel works with good will vs. under compunction might make ourselves an example “proper gentlemen …making it their delight unto you to follow us.” to hear the trees thunder as they fell” Caliban: “I must eat my dinner” Bad to be a useless burden: “… we “gentlemen … doing but as the president” Miranda: would not be chargeable to any of • ”Invader” in ruler’s power; Labor turned to sport you.” daughter physically intercedes No work, no food: “…If there were “Labors of 30 or 40 honest and industrious • Invader plots to marry daughter any which would not work, that he men shall not be consumed to maintain and supplant ruler should not eat” 150 idle varlets” • 13-14 years old “He that will not work shall not eat” • “Nonparell” “… none ought to live idly, but ought to give himself to some vocation, to Pocahontas event details, both real and get his living by, and to do good to slanderous rumor (Smith to marry & rule) others.” “Man not born for himself alone” [Plato via St. -

“Flowers in the Desert”: Cirque Du Soleil in Las Vegas, 1993

“FLOWERS IN THE DESERT”: CIRQUE DU SOLEIL IN LAS VEGAS, 1993-2012 by ANNE MARGARET TOEWE B.S., The College of William and Mary, 1987 M.F.A., Tulane University, 1991 A thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Theatre & Dance 2013 This thesis entitled: “Flowers in the Desert”: Cirque du Soleil in Las Vegas 1993 – 2012 written by Anne Margaret Toewe has been approved for the Department of Theatre & Dance ______________________________________________ Dr. Oliver Gerland (Committee Chair) ______________________________________________ Dr. Bud Coleman (Committee Member) Date_______________________________ The final copy of this thesis has been examined by the signatories, and we Find that both the content and the form meet acceptable presentation standards Of scholarly work in the above mentioned discipline. iii Toewe, Anne Margaret (Ph.D., Department of Theatre & Dance) “Flowers in the Desert”: Cirque du Soleil in Las Vegas 1993 – 2012 Dissertation directed by Professor Oliver Gerland This dissertation examines Cirque du Soleil from its inception as a small band of street performers to the global entertainment machine it is today. The study focuses most closely on the years 1993 – 2012 and the shows that Cirque has produced in Las Vegas. Driven by Las Vegas’s culture of spectacle, Cirque uses elaborate stage technology to support the wordless acrobatics for which it is renowned. By so doing, the company has raised the bar for spectacular entertainment in Las Vegas I explore the beginning of Cirque du Soleil in Québec and the development of its world-tours. -

Educatorsguide

Fun & Learning in the real world nquiry & An educators’ guide E In v e s t i g a t i o n In te rp Design r e t a History t i o ICT cienc n Research S e & T Geography e c h n o Solutions l o g y Investigation C lim a t e Science c h a n Application g e Maths M ! a n k fu in g g learnin The Hampshire & Wight Trust for Maritime Archaeology The Hampshire and Wight Trust for Maritime Archaeology (HMTMA) promotes interest, research and knowledge of maritime archaeology and heritage. The Trust runs a programme of research led fieldwork involving professional archaeologists, volunteers and students. The results of this work are widely disseminated through an innovative programme of education and public outreach including talks, activity days, learning initiatives, workshops, in-school sessions, learning outside the classroom sessions, exhibitions, publications and educational resources. The Heritage Lottery Fund The Heritage Lottery Fund (HLF) sustains and transforms a wide range of heritage through innovative investment in projects with a lasting impact on people and places. As the largest dedicated funder of the UK’s heritage, with around £205 million a year to invest in new projects the HLF are also a leading advocate for the value of heritage to modern life. From museums, parks and historic places to archaeology, natural environment and cultural traditions, HLF invest in every part of our heritage. The HLF has supported more than 30,000 projects allocating £4.5 billion across the UK. The Archaeological Atlas of the Two Seas Some of the material in this booklet has been collected as part of the Archaeological Atlas of the 2 Seas (A2S) project. -

Characters from Shakespeare's the Tempest Revisited: Ferdinand And

Characters from Shakespeare’s The Tempest Revisited: Ferdinand and Caliban in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World and John Fowles’ The Collector Act 1, Scene II: Caliban, Ferdinand, Prospero and Miranda (Folger Shakespeare Library) BA Thesis English Language and Culture, Utrecht University Name: Chantal van der Zanden Student number: 552725 Supervisor: dr. Paul Franssen Second reader: prof. dr. Ton Hoenselaars April 2017 Van der Zanden 2 Table of contents Introduction 3 Chapter 1: The Tempest and Sigmund Freud 8 Chapter 2: Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World 14 Chapter 3: John Fowles’ The Collector 20 Conclusion 26 Works Cited 28 Van der Zanden 3 Introduction The Tempest belongs to William Shakespeare’s last plays and is argued to be the play in which Shakespeare says his goodbyes to theatre, via the magus Prospero who renounces his magic: Now my charms are all o’erthrown, And what strength I have’s mine own, Which is most faint. Now, ‘tis true I must be here confined by you. (Shakespeare Epilogue 1-4) The Tempest is a play prone to modernised readings and full of innovations which makes that the play has seen many dramatic recreations (Brown 13). Ever since the Restoration period, this play has been appropriated and adapted, for instance in John Dryden and William Davenant’s The Tempest or: The Enchanted Island (Vaughan Literary Invocations 155) or the opera of the same name by Thomas Shadwell in 1673 (Vaughan and Vaughan Shakespeare’s Caliban 174). Modern appropriations and adaptations of The Tempest mainly focus on the themes of postcolonialism, postpatriarchy and postmodernism (Zabus 1). -

Sea Venture: a Second Interim Report-Part 1

Thi,In~rrnririonul Journal of Naulrrul Archueology and Underwarcv Erplorurion ( 1985). 14.4: 275-299 Sea Venture: A second interim report-part 1 Jonathan Adams 67 Gains Road, Southsea, Hunts PO4 OPJ, UK Introduction discussed in the first interim report (IJNA 1982, Part 1 of this report is concerned with various 11.4: 333-347). It succeeded in establishing the aspects of the excavation carried out on the identity of the wreck beyond any reasonable wreck of the Sea Venture, lost in 1609 off St. doubt, and with the security resulting from the Georges Island, Bermuda (Fig. I). In particular; formation of the Sea Venture Trust, a long-term the excavation techniques used, and the results view could be brought to bear on the excava- of the preliminary hull surveys, carried out tion, conservation, study. and display of the between November 1982 and November 1983. material from the site. Various classes of material recovered during the Much of the remaining integral structure of excavation will be discussed and illustrated in the ship has been uncovered at one time or part 2; currently in preparation. another by various workers since its discovery The results of the previous phase of work, by Edmund Downing in 1958. In contrast to carried out by a team led by Allan Wingood other wrecks 'worked' only for their contents, on behalf of Bermuda Maritime Museum. were Seu Venture's hull was recognised as being Figure I. Map of Bermuda, showing approximate position of wreck site on Sea Venture Flat. 0305-7445;85/040275 + 25 %03.00/0 01985 The Nautical Archaeology Trust Ltd. -

William Shakespeare's the TEMPEST in the Weitz Center For

RAVE EW ORLDS WilliamB Shakespeare’s N THE TEMPES WT in the Weitz Center for Creativity THE WEITZ CENTER FOR CREATIVITY’s inaugural production of William Shakespeare’s The Tempest will take place 400 years to the week from the play’s first performance in November of 1611. Shakespeare and his company, the King’s Men, had only recently gained access to the indoor Blackfriars theatre in London, and were themselves exploring the possibilities of a new performance space. FAVORITE THEMES OF SHAKESPEARE’s, including family, revenge, redemption, art, magic, and theatre itself vie for dominance in The Tempest, which almost uniquely in the canon has a plot entirely of his own devising. The play also explores ideas about discovery, conquest, colonialism, and government, drawing on a variety of classical and contemporary� sources, including Erasmus’ Naufragium (“The Shipwreck”); Ovid’s Metamorphoses; William Strachey’s eyewitness account of the Sea Venture shipwreck; and Montaigne’s essay “On Cannibals.” LIKE THE VALLARD ATLAS displayed here, The Tempest survives on the one hand as a piece of history, a fixed window into a time when magic was as relevant as science. However, like the images of Caliban on the walls around you, The Tempest has also evolved as our culture has: As both colonization and an awareness of its consequences became more widespread, the play’s portrayal of native/colonist relations emerged as ever more relevant. Just as the space race was beginning, The Tempest’s themes of journey and discovery resonated with a curious and apprehensive population, as exemplified by the 1956 film Forbidden Planet. -

The Virginia Company's Role in the Tempest Barry R. Clarke

Barry R. Clarke, ‘The Virginia Company’s role in The Tempest’ in Petar Penda, editor, The Whirlwind of Passion: New Critical Perspectives on William Shakespeare (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2016). The Virginia Company’s role in The Tempest Barry R. Clarke In December 1606, the London Virginia Council succeeded in persuading several merchant companies and noblemen to finance a new settlement in Virginia.1 Assured of a share in the gold that the Spanish had earlier reported, 2 the adventurers committed enough money to despatch three ships and 144 planters from Blackwall stairs on the Thames across the Atlantic.3 After being delayed for six weeks by strong winds, Captain James Newport found a long passage past the Canaries and the West Indies, and although his navigation eventually failed him, a storm fortuitously delivered him to the Virginia coastline. As the first wave of colonists sailed into Cape Henry on 26 April 1607, the tide of expectation was high, and after sailing forty miles down the River James they pitched a three- sided fort on the north side. Unfortunately, the marshy ground proved to be unwholesome, and typhoid and dysentery soon struck down the new settlers.4 Disease, native attacks, a divided governing body, but mainly famine, eventually brought them to desperation, and only Captain John Smith’s ingenuity and persistence in trading for corn with the Indian chief Powhaton saved the colony from extinction. 1 The voyages sent to Virginia were partly funded by merchant companies such as the Clothworkers Company, the Fishmongers Company, and the Stationer's Company. 2 Alexander Brown, Genesis of the United States, Vol.