Characters from Shakespeare's the Tempest Revisited: Ferdinand And

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

— 1 — 1. Class Title 1 (Simon Keenlyside) 2. Waterhouse: Miranda (1916, Private Collection) the Tempest (1611) Is the Last P

1. Class Title 1 (Simon Keenlyside) 2. Waterhouse: Miranda (1916, private collection) The Tempest (1611) is the last play which Shakespeare wrote alone. It has been described as the most musical of his works, on account of the number of songs in the text, the interpolated masque in the last act, and because it works less through cause and effect than through enchantment, an intrinsically musical quality. It is the only play for which we have any of the original stage music. And according to Wikipedia, it has inspired over four dozen operatic or musical settings. As early as the mid-seventeenth century, managements were adapting the play as a kind of masque, rather than performing the original. 3. Ariel’s Tempest in Columbia I’m also somewhat familiar with it myself. I directed the first performance of The Tempest by American composer Lee Hoiby in the late 1980s, and wrote my own adaptation in 2011 for composer Douglas Allan Buchanan, a 60-minute condensation that we toured to young audiences all over Maryland. 4. Round table discussion at the Met But the version we are watching today is the work of the two people in the middle of this picture: composer/conductor Thomas Adès (b.1971) and the Australian playwright Meredith Oakes (b.1946), seen here with Met General Manager Peter Gelb and stage director Robert Lepage. The picture comes from an intermission feature in the Met’s 2012 Live-in-HD transmission of the opera; I thought of playing it, but it is hard to hear and rather light on information. -

The History of the Jamestown Colony: Seventeenth-Century and Modern Interpretations

The History of the Jamestown Colony: Seventeenth-Century and Modern Interpretations A Senior Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for graduation with research distinction in History in the undergraduate colleges of the Ohio State University By Sarah McBee The Ohio State University at Mansfield June 2009 Project Advisor: Professor Heather Tanner, Department of History Introduction Reevaluating Jamestown On an unexceptional day in December about four hundred years ago, three small ships embarked from an English dock and began the long and treacherous voyage across the Atlantic. The passengers on board envisioned their goals – wealth and discovery, glory and destiny. The promise of a new life hung tantalizingly ahead of them. When they arrived in their new world in May of the next year, they did not know that they were to begin the journey of a nation that would eventually become the United States of America. This summary sounds almost ridiculously idealistic – dream-driven achievers setting out to start over and build for themselves a better world. To the average American citizen, this story appears to be the classic description of the Pilgrims coming to the new world in 1620 seeking religious freedom. But what would the same average American citizen say to the fact that this deceptively idealistic story actually took place almost fourteen years earlier at Jamestown, Virginia? The unfortunate truth is that most people do not know the story of the Jamestown colony, established in 1607.1 Even when people have heard of Jamestown, often it is with a negative connotation. Common knowledge marginally recognizes Jamestown as the colony that predates the Separatists in New England by more than a dozen years, and as the first permanent English settlement in America. -

Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 1991 "In the Hollow Lotus-Land": Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623 Matthew R. Laird College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Laird, Matthew R., ""In the Hollow Lotus-Land": Discord, Order, and the Emergence of Stability in Early Bermuda, 1609-1623" (1991). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539625691. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-dbem-8k64 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •'IN THE HOLLOW LOTOS-LAND": DISCORD, ORDER, AND THE EMERGENCE OF STABILITY IN EARLY BERMUDA, 1609-1623 A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Department of History The College of William and Mary in Virginia In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts by Matthew R. Laird 1991 APPROVAL SHEET This thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Matthew R. Laird Approved, July 1991 -Acmy James Axtell Thaddeus W. Tate TABLE OP CONTENTS Page ACKNOWLEDGMENTS....................................... iv ABSTRACT...............................................v HARBINGERS....... ,.................................... 2 CHAPTER I. MUTINY AND STARVATION, 1609-1615............. 11 CHAPTER II. ORDER IMPOSED, 1615-1619................... 39 CHAPTER III. THE FOUNDATIONS OF STABILITY, 1619-1623......60 A PATTERN EMERGES.................................... -

The Tempest Summary: a Magical Storm

The Tempest Summary: A Magical Storm The Tempest begins on a boat, tossed about in a storm. Aboard is Alonso the King of Naples, Ferdinand (his son), Sebastian (his brother), Antonio the usurping Duke of Milan, Gonzalo, Adrian, Francisco, Trinculo and Stefano. Miranda, who has been watching the ship at sea, is distraught at the thought of lost lives. The storm was created by her father, the magical Prospero, who reassures Miranda that all will be well. Prospero explains how they came to live on this island: they were once part of Milan’s nobility – he was a Duke and Miranda the baby princess. However, Prospero’s brother (Antonio) exiled them – they were placed on a boat and banished, never to be seen again. Prospero summons Ariel, his servant spirit. Ariel explains that he has carried out Prospero’s orders: he destroyed the ship and dispersed its passengers across the island. Prospero instructs Ariel to be invisible and spy on them. Ariel asks when he will be freed and Prospero chastises him for being ungrateful, promising to free him soon, when his work is done. Caliban: Man or Monster? Prospero decides to visit his other servant, Caliban, but Miranda is reluctant, describing him as a monster. Prospero agrees that Caliban can be rude and unpleasant, but is invaluable for the menial tasks he performs for them. When Prospero and Miranda meet Caliban, we learn that he is native to the island, but Prospero turned him into a slave raising issues about morality and fairness in the play. Love at First Sight Ferdinand stumbles across Miranda and they fall in love and decide to marry. -

JUNE 27–29, 2013 Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 P.M. 15579Th

06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 23 JUNE 2 7–29, 2013 Two Works by Stravinsky Thursday, June 27, 2013, 7:30 p.m. 15, 579th Concert Friday, June 28, 2013, 8 :00 p.m. 15,580th Concert Saturday, June 29, 2013, 8:00 p.m. 15,58 1st Concert Alan Gilbert , Conductor/Magician Global Sponsor Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director These concerts are sponsored by Yoko Nagae Ceschina. A production created by Giants Are Small Generous support from The Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer The Susan and Elihu Rose Foun - Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer dation, Donna and Marvin Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Schwartz, the Mary and James G. Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Wallach Family Foundation, and an anonymous donor. Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Filming and Digital Media distribution of this Amar Ramasar , Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* production are made possible by the generos ity of The Mary and James G. Wallach Family This concert will last approximately one and Foundation and The Rita E. and Gustave M. three-quarter hours, which includes one intermission. Hauser Recording Fund . Avery Fisher Hall at Lincoln Center Home of the New York Philharmonic June 2013 23 06-27 Stravinsky:Layout 1 6/19/13 12:21 PM Page 24 New York Philharmonic Two Works by Stravinsky Alan Gilbert, Conductor/Magician Doug Fitch, Director/Designer Karole Armitage, Choreographer Edouard Getaz, Producer/Video Director A production created by Giants Are Small Clifton Taylor, Lighting Designer Irina Kruzhilina, Costume Designer Matt Acheson, Master Puppeteer Margie Durand, Make-Up Artist Featuring Sara Mearns, Principal Dancer* Amar Ramasar, Principal Dancer/Puppeteer* STRAVINSKY Le Baiser de la fée (The Fairy’s Kiss ) (1882–1971) (1928, rev. -

A Jungian Interpretation of the Tempest

University of the Pacific Scholarly Commons University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations Graduate School 1978 A Jungian interpretation of The Tempest Tana Smith University of the Pacific Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Smith, Tana. (1978). A Jungian interpretation of The Tempest. University of the Pacific, Thesis. https://scholarlycommons.pacific.edu/uop_etds/1989 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in University of the Pacific Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. A JUNGil-..~~ INTERPllliTATION OF THE 'rEHPES'r by Tana Smit!1 An Essay Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Univers ity of the Pac ific In Pa rtial Fulfillment of the Requireme nts for the Degree Maste r of Arts Hay 1978 The following psychological interpretation of Shakespeare's 1 The Tempest is unique to articles on the ·same subject which have appeared in literary journals because it applies a purely Jungian reading to the characters in the play. Here each character is shown to represent one of the archetypes which Jung described in his book Archetypes ~ the Collective Unconscious. In giving the play a psychological interpretation, the action must be seen to occur inside Prospera's own unconscious mind. He is experiencing a psychic transformation or what Jung called the individuation process, where a person becomes "a separate, indivisible unity or 2 whole" and where the conscious and unconscious are united. -

ISC Program 16 Web Version+One

RICHARD GRIFFITH PARK FREE SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL JUNE 25 - SEPT 4 the TEMPEST INDEPENDENT SHAKESPEARE CO. SHAKESPEARE SET FREE INDEPENDENT SHAKESPEARE CO. / GRIFFITH PARK FREE SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL Recently, a long time audience member, Frank Lopes, shared a celebrates Shakespeare’s stories and language, the natural beauty sonnet that he wrote about a tree. of the park, and the communion between the audience and the players that takes place night after night. It’s a lovely tree--in fact, you can see it right now, from where you It is a gift to create theater for the Los Angeles community, and our are sitting. If you’re looking towards the Festival stage, it’ s just to efforts are reciprocated tenfold. You really are the engine that pow- the left. Before a performance, you’ll often find actors and audi- ers the Festival. Your financial donations keep the Festival running. ence members sitting under it, enjoying the shade: Your generosity of spirit when we meet you after performances (or Into the sky towards providence do reach onstage at intermission) is deeply moving. We love taking pictures The wise and solemn bows of mighty tree. with you, chatting with you season after season--and in some And when night’s air of summer words do breech, cases, watching you grow up! Those magic words of past set people free. Oh,Tree! What beauty hast thou witnessed here? Every so often a pizza is delivered to us backstage, or a plate of Of lives, of loves, of kingdoms lost to dust, cookies, or a bottle of champagne. -

Text-In-History: the Tempest and New World Cultural Encounter

7H[WLQ+LVWRU\7KH7HPSHVWDQG1HZ:RUOG&XOWXUDO %-6RNRO(QFRXQWHU George Herbert Journal, Volume 22, Numbers 1 and 2, Fall 1998/Spring 1999, pp. 21-40 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\*HRUJH+HUEHUW-RXUQDO DOI: 10.1353/ghj.2013.0062 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/ghj/summary/v022/22.1-2.sokol.html Access provided by University of Athens (or National and Kapodistrian Univ. of Athens) (6 Jun 2015 14:56 GMT) B.J. SOKOL Text-in-History: The Tempest and New World Cultural Encounter In the mid-1960s, Edward Tayler's Renaissance poetry seminar at Columbia University "privileged" me with an unforgettable intro- duction to the enigmas of poetry in history. Tayler chose Marvell's "An Horatian Ode" to incite a discussion of a seeming clash between maintaining an honest historical poetic reading, and decency in the terms of present-day political sensibilities.1 The reconciliation of a personal response to works containing both great literary merit and also outworn, now seemingly ugly, attitudes, remains for me a painful enigma. A great teacher leaves the lucky student with a lifetime's problems or questions. As I recall, Tayler's Socratic teaching demonstrated that, typically, great poetry is untypical: hard to use to exhibit generalities, resistant to reduction, even slippery. The best English Renaissance texts tend to show us up, are humbling. I have come to wonder if like the texts themselves, problems over texts-in-history may demand an attentive and malleable approach to history also, untrammeled by stereotyping. My test case will re-examine ways in which the first English colonial ventures in North America connected with (to use a deliberately neutral term) the composition of The Tempest.1 Lately, readings of this play in terms of colonialism have been rife. -

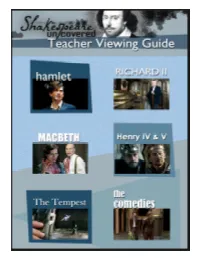

Shakespeare Uncovered Viewing Guide

© 2013 WNET. All rights reserved. Teaching Colleagues, Shakespeare Uncovered, a six-part series airing on PBS beginning on January 25 th , is a teacher’s dream come true. Each episode gives us something that we teachers almost never get: a compelling, lively, totally accessible journey through and around a Shakespeare play, guided by brilliant and plain-spoken experts--all within one hour. I’m not given to endorsements, but oh, I love this series. Why will we teachers love it and why do we need it? • Because, as we learned from the very start of the Folger Library’s Teaching Shakespeare Institute, teachers tend to be more confident, better teachers if they have greater and deeper knowledge of the plays themselves. • Because no matter what our relationship with the plays – we love them, we struggle with them, we’re tired of teaching the same ones, we’re afraid of some of them – we almost never have the time to learn more about them. We are teachers, after all: always under a deadline, we’re reading, grading, prepping, mindful of the next deadline. (And then there’s the rest of our lives . ) Shakespeare Uncovered is your chance to take a deep, pleasurable dive into a handful of plays—ones you know well, others that may be less familiar to you. In six episodes, Shakespeare Uncovered takes on eight plays: Macbeth, Hamlet, The Tempest, Richard II, Twelfth Night and As You Like It, Henry IV, Part I, and Henry V . The host of each episode has plenty of Shakespeare cred--Ethan Hawke, Jeremy Irons, Joely Richardson and her mom, Vanessa Redgrave, for example--but each wants to learn more about the play. -

Tempest Pdf, Epub, Ebook

TEMPEST PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Mercedes Lackey | 394 pages | 06 Dec 2016 | DAW BOOKS | 9780756409036 | English | United States Tempest PDF Book Restoration: Studies in English Literary Culture, — The chastity of the bride is considered essential and greatly valued in royal lineages. Pure singleplayer Want to be a lone sea wolf? HeroCraft PC. Sign In Sign in to add your own tags to this product. National Council of Teachers of English. In , Derek Jarman produced the homoerotic film The Tempest that used Shakespeare's language, but was most notable for its deviations from Shakespeare. The Tempest was one of the staples of the repertoire of Romantic Era theatres. Ariel was—with two exceptions—played by a woman, and invariably by a graceful dancer and superb singer. Tempest is for anyone who is done with alcohol or wants to be done with alcohol, for anyone who wants to change how they see themselves and their possibilities in life. Without these features the characters of the new fonts are similar each other. Pick a Plan Choose the level of support you need from our three membership options. Pirate cooperation Share the world of Tempest between you and your friends. This article is about the Shakespeare play. Shakespeare remakes. Upon the restoration of the monarchy in , two patent companies —the King's Company and the Duke's Company —were established, and the existing theatrical repertoire divided between them. Gonzalo's description of his ideal society 2. At least two other silent versions, one from by Edwin Thanhouser , are known to have existed, but have been lost. -

A True Reportory of the Wreck and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates

Note: Britain was in the earliest stages of exploring and colonizing North America around the time that Shakespeare wrote The Tempest. Many plot elements and themes in the play reflect the beginning of colonialism in Britain. As well, the following document may very well have inspired the story of shipwrecked nobles that makes up the plot to the play. A True Reportory of the Wreck and Redemption of Sir Thomas Gates, Knight, upon and from the Islands of the Bermudas: His Coming to Virginia and the Estate of that Colony Then and After, under the Government of the Lord La Warr, July 15, 1610, written by William Strachey, Esquire A most dreadful tempest (the manifold deaths whereof are here to the life described), their wreck on Bermuda, and the description of those islands EXCELLENT LADY, Know that upon Friday late in the evening we brake ground out of the sound of Plymouth, our whole fleet then consisting of seven good ships and two pinnaces, all which, from the said second of June unto the twenty-third of July, kept in friendly consort together, not a whole watch at any time losing the sight each of other. Our course, when we came about the height of between 26 and 27 degrees, we declined to the northward, and according to our governor’s instructions, altered the trade and ordinary way used heretofore by Dominica and Nevis in the West Indies and found the wind to this course indeed as friendly, as in the judgment of all seamen it is upon a more direct line, and by Sir George Somers, our admiral, had been likewise in former time sailed, being a gentleman of approved assuredness and ready knowledge in seafaring actions, having often carried command and chief charge in many ships royal of Her Majesty’s, and in sundry voyages made many defeats and attempts in the time of the Spaniard's quarreling with us upon the islands and Indies, etc. -

Shakespeare's Virgil : Empathy and the Tempest

chapter 4 Shakespeare’s Virgil : empathy and Th e Tempest Leah Whittington Empathy is a subject that could easily fi nd a home in any one of the sec- tions of this volume. After all, early modern thinking about emotional identifi cation with another person – whether described as pity, compas- sion, or fellow-feeling – draws from the wellsprings of both classical and Christian ethics. To attempt to separate one from the other may be not only impossible but also undesirable, especially given that Shakespearean drama often takes its energy from the very confl ation or juxtaposition of ethical registers. Th e awakening of Hermione’s statue in Th e Winter’s Tale is part Ovidian metamorphosis, part Christian resurrection. Lear’s recon- ciliation with Cordelia derives much of its power from the vertiginous blending of New Testament forgiveness and Seneca’s theory of reciprocal benefi ts. 1 Nevertheless, in this chapter I aim to treat Shakespeare’s ethics of empathy as a facet of his classicism, both because the classical aspects of empathy in Shakespearean drama are less well understood than the Christian and because a classically focused consideration of empathy illu- minates Th e Tempest in a new way. Th e impetus for this approach comes from the rhetorical orientation of the humanist curriculum, in which learning to speak well also meant learning to inhabit and imitate the liter- ary voices of the classical past. 2 While Shakespeare would have had access to ethical assessments of fellow-feeling in a variety of philosophical, reli- gious, and political texts, his education in empathy in the schoolroom began through reading and imitating literary works of classical antiquity.