Seamless, Sustainable, Smart Reimagining Novato’S Public Transportation Network

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Town of Leesburg

DRAFT LOUDOUN COUNTY Transit Management Analysis Report Prepared for: Prepared by: October 2013 Table of Contents 1. Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................3 Background ..............................................................................................................................................................................................3 Study Purpose .......................................................................................................................................................................................3 2. Institutional Stakeholders and Existing Funding .....................................................................4 Loudoun County .................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Town of Leesburg .............................................................................................................................................................................. 4 Northern Virginia Transportation Authority (NVTA) .................................................................................................. 4 Northern Virginia Transportation Commission (NVTC) ........................................................................................... 4 Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority (WMATA) ...............................................................................5 -

Lipiment JM POTTER MUSIC STORE

;V> jfrj.i '*-• »s& • <•' * vr( * feV: iss-tip ase;: (EgStt S ~ t -;- .jm* ip * Sfo , wj*. jfc-? >21 f- Tt'"'s' ' ^ 4 * v 1 ?^S8«s • NORWALK/CONNECTICUT, TUESDAY, OCTOBER 25, 1881. • v' '• : VOL. LXIV.-NUMBER 43 WHOLE NUMBER 1764. Discoveries In Iceland. ; r The Origin of Diptheria. j NORWALK GAZETTE, J. G. GREGORY & CO. REAL ESTATE. EKGLAITD TO AMERICA. KNOWING. ruefully explained "the deuced awkward Readman Bros., scrape" he had got himself into by speaking %'•:•$•'h Professor Horatio C. Wood, who has been PUBLISHED EVERY TUESDAY MORRINO. ' ' .' ' BY JULIA .0. It. DOltK." out at a time when common sense should have William Lee Howard has just returned Apartments to Let. James Abram Garfield. engaged with Dr. Henry Formad in re Photographers, warned him that the better part of wisdom from Iceland where he was'sent early in the Successors to EDWARD P. WEED, N the Brick Houses on Leonard street. In : : searches as to the origin of diptheria, de BORN NOVEMBER 19, 1831. -V Onesummer day, to a young child Isaid, was to remain silent. summer by the American Geographical So The Second Oldest Paper in the State. t quire at LEONARD'S COAL OFFICIO. livered a lecture upon the subject before the No. 38 Wall Street, Norwalk, Ct., GAZETTE BUI1DINS, NORWAIK DIED PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES 9BP- "Write to thy mother, boy." With earn "Ob, was there ever anything so vexing ?" ciety in order to settle some disputed points Views of Residences taken at short notice; Academy of Natural Sciences at Philadel ^ , V, S TEMBER 19, 1881. -

Business Outreach Committee (BOC) Contracting Newsletter #27, Spring

BOC Newsletter #27, Spring 2015, Page 1 of 2 Business Outreach Committee (BOC) Contracting Newsletter #27, Spring 2015 The goal of the BOC is to assist small and disadvantaged companies in doing business with Bay Area transportation agencies. UPCOMING CONTRACTING OPPORTUNITIES (SELECTED AGENCIES): GOLDEN GATE BRIDGE, HIGHWAY & TRANSPORTATION DISTRICT (GGBHTD) Solicitation Letter: Purchase and Installation of a Wireless Due Date*: May 2015 Est.$: 90K Infrastructure Upgrade Third Party Administrator for Public Liability and Fleet Claims Due Date*: May 2015 Est.$: 350K Investigation and Adjustment Services Toll Plaza Administration Building Improvements Due Date*: May 2015 Est.$: 500K San Rafael Improvements Employee Parking Lot Due Date*: TBD Est.$: 1.5M Larkspur Ferry Terminal Sewer and Fuel Systems Rehabilitation Due Date*: TBD Est.$: 800K Bus Stop Shelter & Signage Improvements Due Date*: TBD Est.$: 500K South Approach and Pier Security Improvements Due Date*: TBD Est.$: 4M Sausalito Ferry Terminal Gangway and Pier Improvements, Due Date*: TBD Est.$: 10M Construction San Francisco Ferry Terminal Gangway and Pier Improvements, Due Date*: TBD Est.$: 20M Construction METROPOLITAN TRANSPORTATION COMMISSION (MTC) Business Process Identification and Documentation Project Due Date*: May 8, 2015 Est. $: TBD Compensation Study Due Date*: May 13, 2015 Est. $: TBD Program for Arterial System Synchronization (PASS) Due Date*: May 15, 2015 Est. $: TBD SHRP2 Implementation Assistance and Technical Guidance and Due Date*: May 22, 2015 Est. $: TBD Support 511 System Integrator, Data Management & Dissemination, and Issue Date*: TBD Est. $: TBD Interactive Voice Response (IVR) Phone System Bay Area Infrastructure Financing Authority (BAIFA) I-680 Express Issue Date*: TBD Est. $: TBD Lanes Civil Construction Project Maintenance, Diagnostic and Repair Services of Traffic Operations Issue Date*: TBD Est. -

Michigan Agricultural College Association 2 the M

i'%^- 11! L.; $*W '..'£&?•>.;. -... -JB IMP Published by the lift Michigan Agricultural College Association 2 THE M. A. C. RECORD. Northeast Michigan. President—E. C. Geyer, '13, 511 Perry St., THE M. A. C. RECORD Saginaw, W. S. Entered as second-class matter October 30, Vice President—Roscoe W. Rice, '17, 615 1916, at the post office at East Lansing, N. Farragut St., Bay City Michigan, under the Act of Secretary—Dan H. Ellis, '07, 616 Owen St., March 3, 1879. Saginaw. Treasurer—Z. E. Colbv, '09, 213 Fraser St., Published every Friday during the College Bay City. Year by the Michigan Agricultural Lenawee County. College Association. President—C. L. Coffeen, '12, Adrian. Secretary—-Jessie Illenden, '19, Adrian. H. E. Thomas, '85, Lansing - President St. Joseph County. H. B. Gunnison, '00, Detroit, Vice President President^W. T. Langley, '82, Constan- J. H. Prost, '04, Chicago - - Treasurer tine, R. F. D. C. W. McKibbin, '11, Lansing, Secy.—Sam Hagenbuck, '10, Three Rivers. Secretary and Editor Berrien County. May E. Foley, '18 - Assistant Secretary President—Charles Richards, Benton Har Members of Executive Committee. bor, R. R. Fair Plains. Elected at Large: Vice-President—Beatrice Jakway, '17. C. S. Langdon; '11, Hubbardston. Secretary—Kittie Handy, '16, Court House, A. C. Anderson, '06, Flint. St. Joseph. Mrs. Helen Esselstyn Wood, '09, Lansing. Treasurer—Willard Sanborn, '13. Livingston County. MEMBERSHIP IN THE M. A. C. ASSOCIA President, G. P. Burkhart, '10, Fowlerville. TION which includes subscription to Secretary, F. S. Dunks, '05, Court House, the Record, $2.00 PER YEAR. Howell. Make Remittances payable to the M. -

Ron Cowan Father of the Ferries 1934-2017

“The Voice of the Waterfront” February 2017 Vol.18, No.2 RON COWAN FATHER OF THE FERRIES 1934-2017 No Gag Orders Here Quenching the Thirst New S.F. Green Building Law S.F. Bay Needs Fresh Water COMPLETE FERRY SCHEDULES FOR ALL SF LINES NEW YEAR, NEW WINES AT ROSENBLUM CELLARS JACK LONDON SQUARE 10 CLAY STREET « OAKLAND, CA « 1.877.GR8.ZINS DAYS OPEN 7 DAYS A WEEK PATIO OPEN TILL 9PM ON FRIDAY & SATURDAY! TASTE WINES WHILE ENJOYING OUR BAY VIEWS! 2 FOR 1 WINE JUST A FERRY TASTINGS! RIDE FROM SF GET 2 TASTINGS RIGHT BY THE JACK FOR THE PRICE LONDON SQUARE OF 1 WITH THIS AD FERRY TERMINAL ©2017 ROSENBLUM CELLARS. OAKLAND, CALIFORNIA | WWW.ROSENBLUMCELLARS.COM 2 bay-crossing-rosenblum-mag-10x5.inddFebruary 2017 1 www.baycrossings.com 1/13/17 3:01 PM Great food to celebrate life in the City! Enjoy a ten minute walk from the Ferry Building or a short hop on the F-Line Crab House at Pier 39 Voted “Best Crab in San Francisco” Sizzling Skillet-roasted Mussels, Shrimp & Crab Romantic Cozy Fireplace Stunning Golden Gate Bridge View Open Daily 11:30 am - 10 pm 2nd Floor, West Side of Pier 39 Validated Parking crabhouse39.com 415.434.2722 DO YOU KNOW WHO CAUGHT YOUR FISH? ... SCOMA’S DOES! Franciscan Crab Restaurant Local shermen help Scoma’s to achieve our goal of providing the freshest sh possible to our guests; from our PIER to your PLATE Scoma’s is the only restaurant Open Daily 11:30 am - 11 pm Pier 43 1/2 Validated Parking in San Francisco where sherman pull up to our pier to sell us sh! Whole Roasted Dungeness Crab Breathtaking Views 415.362.7733 Whenever our own boat cannot keep up with customer demand, Scoma’s has Bay Side of Historic Fisherman’s Wharf franciscancrabrestaurant.com always believed in supporting the local shing community. -

General Manager's Report

Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit District General Manager’s Report – July 2018 5401 Old Redwood Highway, Suite 200 Petaluma, CA 94954 Tel: (707) 794-3330Fax: (707) 794-3037 www.SonomaMarinTrain.org Larkspur Extension Project ▪ Larkspur Station work continues with the construction of the station platform, ramp and rough grading for the parking lot. ▪ Reconstruction of the roadway portion of the Andersen Drive at-grade crossing was completed on July 3rd with the reopening of the roadway. ▪ Grading for track construction is underway from the tunnel to the station. ▪ Work began on the San Rafael Creek bridge. Andersen Drive At-Grade Crossing P a g e | 2 of 24 Andersen Drive At-Grade Crossing Larkspur Station Platform Construction P a g e | 3 of 24 Larkspur Station Platform Ramp – concrete formwork P a g e | 4 of 24 South Cal Park Tunnel to Station placing the gravel ballast for the track P a g e | 5 of 24 Excavation for utilities from near the Auburn Street Bridge P a g e | 6 of 24 San Rafael Creek Bridge – foundation construction P a g e | 7 of 24 COMMUNITY OUTREACH Community Outreach| Presentations and Community Events It’s summer in Marin and Sonoma counties, which means warm weather and activities for the whole family to enjoy. SMART’s booth at the Marin County Fair was a popular stop. Many took the opportunity to beat the traffic and avoid paying for parking by taking the train to the Marin Civic Center. As part of a new summer safety outreach initiative, SMART staff introduced a new engagement technique to connect with families and young children about the importance of safety near tracks and trains. -

SMART 3 Year Anniversary Presentation

Happy Anniversary SMART! SMART is currently a 45-mile rail line with 12 stations serving cities in Sonoma and Marin counties, and with a bicycle and pedestrian pathway network along the rail corridor. An extension of the rail line is being constructed to offer passenger rail service to Windsor in 2021. As an integral part of the fabric of the North Bay, SMART has been here through fires, floods, economic recessions and a viral pandemic and we’ll continue to proudly serve in the good times and through the rough patches. In 2020, in response to COVID-19, SMART staff have implemented train sanitizing protocols to protect the health of our passengers and staff. We are very proud of the team of dedicated professionals who make up SMART staff and the vital service they provide to the North Bay. Eric Lucan, Barbara Pahre, Chair, SMART Board of Directors Vice Chair, SMART Board of Directors It Began With a Vision In 1997, the Sonoma/Marin Multi-Modal Transportation and Land Use Study by Peter Calthorpe laid out a vision for re-establishing passenger rail in the North Bay. 3 The SMART Commission In 1998 a two-part sales tax measure was placed on the ballot to raise funds for passenger rail. Local environmentalists pick up the pieces Measure B, the plan for passenger rail after defeat of passed with a 70% majority, and Measure transit tax plan C – providing the funding for the plan Sonoma County Independent failed to get a simple majority. November 5-11, 1998 In the wake of Measure B’s strong showing at the ballot box, The Sonoma Marin Area Rail Transit (SMART) Commission was formed. -

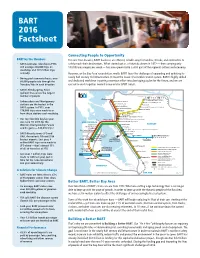

BART 2016 Factsheet

BART 2016 Factsheet Connecting People to Opportunity BART by the Numbers For over four decades, BART has been an efficient, reliable way for families, friends, and commuters to • BART estimates ridership in FY16 safely reach their destinations. What started out as a futuristic dream in 1972 — then carrying only will average 430,000 trips on 100,000 passengers per week— has now grown to be a vital part of the regional culture and economy. weekdays and 129 million trips annually. However, as the Bay Area’s population swells, BART faces the challenge of upgrading and updating its • During peak commute hours, over nearly half century old infrastructure to meet the needs of a modern transit system. BART’s highly skilled 60,000 people ride through the and dedicated workforce is putting enormous effort into developing a plan for the future, and we are Transbay Tube in each direction. excited to work together toward a new era for BART transit. • BART’s Pittsburg/Bay Point (yellow) line carries the largest AMTRAK SAN JOAQUIN number of people. Pittsburg Center Station Antioch Station Richmond Pittsburg/Bay Point El Cerrito del Norte • Embarcadero and Montgomery North Concord/Martinez El Cerrito Plaza stations are the busiest in the Concord North Berkeley Pleasant Hill/Contra Costa Centre BART system. In FY15, over Downtown Berkeley Walnut Creek 170,000 trips were made to or Ashby Lafayette from these stations each weekday. Orinda Rockridge MacArthur TIMED TRANSFER (SOUTHBOUND) • Our top ridership day last year West Oakland 19th St/Oakland TIMED TRANSFER (NORTHBOUND) 12th St/Oakland City Center was June 19, 2015 for the SAN FRANCISCO Embarcadero Lake Merritt EAST BAY Warriors Championship Parade Montgomery St Fruitvale Powell St and A’s game —548,076 trips! Coliseum TRANSFER FOR SERVICE TO OAKLAND INTERNATIONAL AIRPORT Civic Center/UN Plaza MUNI METRO San Leandro • BART directly serves SFO and Bay Fair 16th St Mission Castro Valley Dublin/Pleasanton OAK, the nation’s 7th and 35th 24th St Mission Glen Park Oakland busiest airports. -

Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit District

Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit District General Manager’s Report – December 2019 5401 Old Redwood Highway, Suite 200 Petaluma, CA 94954 Tel: (707) 794-3330 Fax: (707) 794-3037 www.SonomaMarinTrain.org P a g e | 2 of 29 Your SMART Team P a g e | 3 of 29 Gary Phillips, Chair, SMART Board of Directors Congressman Huffman Judy Arnold, Chair, Transportation Authority of Marin P a g e | 4 of 29 Barbara Pahre, President, Golden Gate Bridge Catherine Way, Mayor, City of Larkspur Jake Mackenzie, MTC Commissioner P a g e | 5 of 29 Larkspur Station Opening Day P a g e | 6 of 29 P a g e | 7 of 29 Congressman Huffman participated in the Band Holiday Express Train at Larkspur Station P a g e | 8 of 29 Larkspur Station Opening Day P a g e | 9 of 29 P a g e | 10 of 29 P a g e | 11 of 29 Novato Downtown Ribbon Cutting Ceremony December 14, 2019 P a g e | 12 of 29 Congressman Huffman, City of Novato Mayor Athas, and Supervisor Arnold First Train stopping in Downtown Novato P a g e | 13 of 29 COMMUNITY OUTREACH SMART hosted the Larkspur Station Ribbon Cutting Ceremony on Friday, December 13, 2019, to celebrate the commencement of passenger service to Larkspur that is coordinated with the ferry to provide an economical, climate-friendly and stress-free way to travel between the North Bay and San Francisco. The new Larkspur station will be a gateway to the Bay for commuters and visitors alike. -

Resolution #20-9

BALTIMORE METROPOLITAN PLANNING ORGANIZATION BALTIMORE REGIONAL TRANSPORTATION BOARD RESOLUTION #20-9 RESOLUTION TO ENDORSE THE UPDATED BALTIMORE REGION COORDINATED PUBLIC TRANSIT – HUMAN SERVICES TRANSPORTATION PLAN WHEREAS, the Baltimore Regional Transportation Board (BRTB) is the designated Metropolitan Planning Organization (MPO) for the Baltimore region, encompassing the Baltimore Urbanized Area, and includes official representatives of the cities of Annapolis and Baltimore; the counties of Anne Arundel, Baltimore, Carroll, Harford, Howard, and Queen Anne’s; and representatives of the Maryland Departments of Transportation, the Environment, Planning, the Maryland Transit Administration, Harford Transit; and WHEREAS, the Baltimore Regional Transportation Board as the Metropolitan Planning Organization for the Baltimore region, has responsibility under the provisions of the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation (FAST) Act for developing and carrying out a continuing, cooperative, and comprehensive transportation planning process for the metropolitan area; and WHEREAS, the Federal Transit Administration, a modal division of the U.S. Department of Transportation, requires under FAST Act the establishment of a locally developed, coordinated public transit-human services transportation plan. Previously, under MAP-21, legislation combined the New Freedom Program and the Elderly Individuals and Individuals with Disabilities Program into a new Enhanced Mobility of Seniors and Individuals with Disabilities Program, better known as Section 5310. Guidance on the new program was provided in Federal Transit Administration Circular 9070.1G released on June 6, 2014; and WHEREAS, the Federal Transit Administration requires a plan to be developed and periodically updated by a process that includes representatives of public, private, and nonprofit transportation and human services providers and participation by the public. -

2019 Annual Report

2019 Annual Report Fiscal Year 2018-2019 5401 Old Redwood Highway | Suite 200 | Petaluma, CA 94954 SonomaMarinTrain.org Table of Contents About the Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit District .................1 Message from the Chair of the Board of Directors ..................2 Passenger Rail Service ........................................................................3 Grand Opening of New Stations .....................................................4 Operations ..............................................................................................5 Capital Projects .................................................................................. 10 Communications and Marketing ................................................. 13 Safety and Security ........................................................................... 19 Human Resources ............................................................................. 20 Financial Information ....................................................................... 21 Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit District About the Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit District (SMART) Sonoma-Marin Area Rail Transit (SMART) is the Bay Area’s newest passenger rail service providing a safe, reliable and congestion-free transportation option for Marin and Sonoma counties. The current 45-mile system includes stations in the Sonoma County Airport area, Santa Rosa, Rohnert Park, Cotati, Petaluma, Novato, San Rafael, and Larkspur. SMART’s system also includes a bicycle and pedestrian pathway along portions -

EMMA Official Statement

NEW ISSUE – BOOK ENTRY ONLY RATINGS: Moody’s (2020 Bonds): Aaa Long Term Standard & Poor’s (2020C-1 Bonds): AAA Short Term Standard & Poor’s (2020C-2 Bonds): A-1+ See “Ratings” herein. In the opinion of Orrick, Herrington & Sutcliffe LLP, Bond Counsel to the District, based upon an analysis of existing laws, regulations, rulings and court decisions, and assuming, among other matters, the accuracy of certain representations and compliance with certain covenants, interest on the 2020C-1 Bonds is excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes under Section 103 of the Internal Revenue Code of 1986. In the further opinion of Bond Counsel, interest on the 2020C-1 Bonds is not a specific preference item for purposes of the federal alternative minimum tax. Bond Counsel is also of the opinion that interest on the 2020 Bonds is exempt from State of California personal income taxes. Bond Counsel further observes that interest on the 2020C-2 Bonds is not excluded from gross income for federal income tax purposes under Section 103 of the Code. Bond Counsel expresses no opinion regarding any other tax consequences related to the ownership or disposition of, or the amount, accrual or receipt of interest on, the 2020 Bonds. See “TAX MATTERS.” $700,000,000 SAN FRANCISCO BAY AREA RAPID TRANSIT DISTRICT GENERAL OBLIGATION BONDS $625,005,000 $74,995,000 (ELECTION OF 2016), (ELECTION OF 2016), 2020 SERIES C-1 2020 SERIES C-2 (FEDERALLY TAXABLE) (GREEN BONDS) (GREEN BONDS) Dated: Date of Delivery Due: As shown on inside cover The San Francisco Bay Area Rapid Transit District General Obligation Bonds (Election of 2016), 2020 Series C-1 (Green Bonds) (the “2020C-1 Bonds”) and 2020 Series C-2 (Federally Taxable) (Green Bonds) (the “2020C-2 Bonds” and, together with the 2020C-1 Bonds, the “2020 Bonds”) are being issued to finance specific acquisition, construction and improvement projects for District facilities approved by the voters and to pay the costs of issuance of the 2020 Bonds.