Why Sound Recordings Should Never Be Considered Works Made for Hire by Dustin Osborne

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

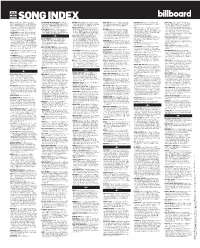

2021 Song Index

FEB 20 2021 SONG INDEX 100 (Ozuna Worldwide, BMI/Songs Of Kobalt ASTRONAUT IN THE OCEAN (Harry Michael BOOKER T (RSM Publishing, ASCAP/Universal DEAR GOD (Bethel Music Publishing, ASCAP/ FIRE FOR YOU (SarigSonnet, BMI/Songs Of GOOD DAYS (Solana Imani Rowe Publishing Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI/Music By Publishing Deisginee, APRA/Tyron Hapi Publish- Music Corp., ASCAP/Kid From Bklyn Publishing, Cory Asbury Publishing, ASCAP/SHOUT! MP Kobalt Music Publishing America, Inc., BMI) Designee, BMI/Songs Of Universal, Inc., BMI/ RHLM Publishing, BMI/Sony/ATV Latin Music ing Designee, APRA/BMG Rights Management ASCAP/Irving Music, Inc., BMI), HL, LT 14 Brio, BMI/Capitol CMG Paragon, BMI), HL, RO 23 Carter Lang Publishing Designee, BMI/Zuma Publishing, LLC, BMI/A Million Dollar Dream, (Australia) PTY LTD, APRA) RBH 43 BOX OF CHURCHES (Lontrell Williams Publish- CST 50 FIRES (This Little Fire, ASCAP/Songs For FCM, Tuna LLC, BMI/Warner-Tamerlane Publishing ASCAP/WC Music Corp., ASCAP/NumeroUno AT MY WORST (Artist 101 Publishing Group, ing Designee, ASCAP/Imran Abbas Publishing DE CORA <3 (Warner-Tamerlane Publishing SESAC/Integrity’s Alleluia! Music, SESAC/ Corp., BMI/Ruelas Publishing, ASCAP/Songtrust Publishing, ASCAP), AMP/HL, LT 46 BMI/EMI Pop Music Publishing, GMR/Olney Designee, GEMA/Thomas Kessler Publishing Corp., BMI/Music By Duars Publishing, BMI/ Nordinary Music, SESAC/Capitol CMG Amplifier, Ave, ASCAP/Loshendrix Production, ASCAP/ 2 PHUT HON (MUSICALLSTARS B.V., BUMA/ Songs, GMR/Kehlani Music, ASCAP/These Are Designee, BMI/Slaughter -

Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom Kevin Kshitiz Bhatia

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Law School Student Scholarship Seton Hall Law 5-1-2014 Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom Kevin Kshitiz Bhatia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship Recommended Citation Bhatia, Kevin Kshitiz, "Ozymandias: Kings Without a Kingdom" (2014). Law School Student Scholarship. 441. https://scholarship.shu.edu/student_scholarship/441 Ozymandias: Kings without a Kingdom Ozymandias is an English sonnet written by poet Percy Shelly in 1818. The sonnet reads: “I met a traveller from an antique land who said: Two vast and trunkless legs of stone stand in the desert. Near them, on the sand, half sunk, a shattered visage lies, whose frown, and wrinkled lip, and sneer of cold command, tell that its sculptor well those passions read which yet survive, stamped on these lifeless things, the hand that mocked them and the heart that fed: And on the pedestal these words appear: ’My name is Ozymandias, king of kings: Look on my works, ye mighty, and despair!’ Nothing beside remains. Round the decay of that colossal wreck, boundless and bare the lone and level sands stretch far away.”75 There are several conflicting accounts regarding Shelly’s inspiration for the sonnet, but the most widely accepted story tells that Percy Shelly was inspired by the arrival in Britain of a statute of the Egyptian pharaoh Ramesses II. Observing the irony of a pharaoh’s statute, which was created to glorify the omnipotence of the ruler, being carried into port as a mere collectible in a museum, Shelly wrote the sonnet to summarize a particular irony that presents itself repeatedly throughout history. -

CWR Sender ID and Codes

CWR Sender ID Codes CWR06-1972_Specifications_Overview_CWR_sender_ID_and_codes_2021-09-27_EN.xlsx Publisher Submitter Code Submitter Start Date End Date (dd/mm/yyyy) Number (dd/mm/yyyy) To all societies 00 Royal Flame Music Gmbh 104 00585500247 21/08/2015 Rdb Conseil Rights Management 112 00869779543 6/01/2020 Mmp.Mute.Music.Publishing E.K. 468 814224861 25/07/2019 Seegang Musik Musikverlag E.K. 772 792755298 25/07/2019 Les Editions Du 22 Decembre 22D 450628759 4/11/2010 3tone Publishing Limited 3TO 1050225416 25/09/2020 4AD Music Limited 4AD 293165943 15/03/2010 5mm Publishing 5MM 00492182346 22/11/2017 AIR EDEL ASSOCIATES LTD AAL 69817433 7/01/2009 Ceg Rights Usa AAL 711581465 17/12/2013 Ambitious Media Productions AAP 00868797449 31/08/2021 Altitude Balloon AB 722094072 6/11/2013 Abc Digital Distribution Limited ABC 00599510310 8/06/2020 Editions Abinger Sprl ABI 00858918083 23/11/2020 Abkco Music Inc ABM 00056388746 21/11/2018 ABOOD MUSIC LIMITED ABO 420344502 31/03/2009 Alba Blue Music Publishing ABP 00868692763 2/06/2021 Abramus Digital Servicos De Identificacao De Repertorio ABR 01102334131 16/07/2021 Ltda Absilone Technologies ABS 00546303074 5/07/2018 Almo Music of Canada AC 201723811 1/08/2001 2/10/2006 Accorder Music Publishing America ACC 606033489 5/09/2013 Accorder Music Publishing Ltd ACC 574766600 31/01/2013 Abc Frontier Inc ACF 01089418623 20/07/2021 Galleryac Music ACM 00600491389 24/04/2017 Alternativas De Contenido S L ACO 01033930195 17/12/2020 ACTIVE MUSIC PUBLISHING PTY LTD ACT 632147961 16/11/2016 Audiomachine -

Hercules Returns Music Credits

Composer Contemporary Footage Philip Judd Music Co-ordinator Gary Hardman Music Licensing Christine Woodruff Music Video Director Mark Hartley - Music - "Tie A Yellow Ribbon Round The Old Oak Tree" Written by I. Levine/L. Russell Brown (Peermusic) "The Great Pretender" Written by Buck Ram (Peermusic) "Physical" Written by T. Shaddick/S. Kipner (Stephen Kipner Music/Terry Shaddick Music/MCA Gilby) "My Way" Written by P. Anka/J. Revaux/C. Francoise/G. Thibault (MCA Music) "Macho Man" Written by H. Belolo/V. Willis/B. Whitehead/J. Marali (Black Scorpio/AMCOS) "Since I Don't Have You" Written by Beaumont/Vogel/Verscharen/Lester/Taylor/Rock/Martin (Peermusic) "I Know What Boys Like" Written by C. Butler (Mushroom Music Pty Ltd) "Hercules Rap" Written and Performed by Des Mangan Music by Phil Rigger Original Italian film (title not mentioned in tail credits): Music Composed and Conducted by Piero Umiliani Music recorded by Firmamento, Rome (As per the credit that appears in the film within the film): The film explains the music in the film by having Bruce Spence’s character work a record player: Soundtrack: The soundtrack was never given a full-blooded commercial release, but copies did find their way into the marketplace to cater for cult enthusiasts. It was allegedly “based on the feature film”, but featured more Des Mangan and Phil Rigger than Phil Judd: CD Screentrax/Polydor 5212022 1993 Includes dialogue from the film. Produced and Arranged by: Phil Rigger Recorded at Fineline Studio, Randwick Engineered and recorded by Phil Rigger Assisted by Keith Cooper Mastered at 301 Studios, Sydney by Steve Smart Project co-ordinators: Screensong Pty. -

Classement Des 200 Premiers Singles Fusionnés Par Gfk Année 2012

Classement des 200 premiers Singles Fusionnés par GfK année 2012 Rang Artiste Titre Label Editeur Distributeur Physique Distributeur Numérique Genre 1 MICHEL TELO AI SE EU TE PEGO ULM MERCURY MUSIC GROUP UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION MERCURY VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 2 GOTYE SOMEBODY THAT I USED TO KNOW CASABLANCA MERCURY MUSIC GROUP UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION MERCURY POP ROCK 3 CARLY RAE JEPSEN CALL ME MAYBE INTERSCOPE RECORDS POLYDOR UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION POLYDOR VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 4 PSY GANGNAM STYLE ULM MERCURY MUSIC GROUP UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION MERCURY VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 5 ADELE SKYFALL Beggars Naïve NAIVE BEGGARD GROUP / XL RECORDING INDE 6 LYKKE LI I FOLLOW RIVERS WEA WEA WARNER MUSIC FRANCE WARNER MUSIC FRANCE VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 7 LANA DEL REY VIDEO GAMES POLYDOR POLYDOR UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION POLYDOR VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 8 SHAKIRA JE LAIME A MOURIR Norte JIVE EPIC GROUP SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT SONY MUSIC JIVE EPIC GROUP VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 9 SEXION D ASSAUT AVANT QU ELLE PARTE Jive Epic JIVE EPIC GROUP SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT SONY MUSIC JIVE EPIC GROUP VARIETE FRANCAISE 10 RIHANNA DIAMONDS DEF JAM FRANCE Def Jam Recordings France UNIVERSAL MUSIC FRANCE UNIVERSAL MUSIC DIVISION DEF JAM VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 11 ASAF AVIDAN THE MOJOS ONE DAY RECKONING SONG Columbia Deutschland JIVE EPIC GROUP SONY MUSIC ENTERTAINMENT SONY MUSIC COLUMBIA GROUP VARIETE INTERNATIONALE 12 BIRDY SKINNY LOVE WEA WEA WARNER -

Wesingpopmanualger.1712448956

Inhalt UPDATE DES Wii-MENÜS 2 VOR DEM SPIEL 2 ANSCHLIESSEN DES USB-MIKROFONS 3 VORBEREITUNG 4 DAS SPIEL 4 DER SPIELBILDSCHIRM 5 LIEDERAUSWAHL 7 PARTY-MODUS 9 SOLOMODUS 11 ÜBUNGEN 11 PREISE 12 KARAOKE 12 JUKEBOX 12 CHARTS 12 OPTIONEN 12 PAUSENMENÜ 13 ERGEBNISSE 15 MITWIRKENDE 16 MUSIK-QUELLEN 17 1 Update des Wii-Menüs Wenn Sie die Disc das erste Mal in Ihre Wii-Konsole einlegen, wird überprüft, ob die aktuellste Version des Wii- Menüs verfügbar ist. Falls nicht, erscheint automatisch der Wii-System-Update-Bestätigungsbildschirm. Wählen Sie O.K., um fortzufahren. Das Update kann einige Minuten in Anspruch nehmen und es ist möglich, dass dabei dem Wii-Menü neue Kanäle hinzugefügt werden. Beachten Sie bitte, dass dieWii-Konsole über das aktuellste Update des Wii-Menüs verfügen muss, um diese Disc abzuspielen. HINWEIS: Sollte nach dem Durchführen des Updates im Disc-Kanal nicht der Titel der eingeschobenen Disc angezeigt werden, ist ein weiteres Update notwendig. Wiederholen Sie in diesem Falle die oben genannte Vorgehensweise. Während eines Updates des Wii-Menüs hinzugefügte Kanäle werden im Speicher der Wii-Konsole abgelegt, sofern genügend Speicherplatz vorhanden ist. Diese zusätzlichen Kanäle können auf dem Datenverwaltungsbildschirm in den Wii-Optionen gelöscht werden. Wurden die Kanäle gelöscht, können sie später im Wii-Shop-Kanal erneut kostenlos heruntergeladen werden. Wenn das Wii-Menü auf den neuesten Stand gebracht wird, werden Speicherdaten oder Programme, die auf nicht autorisiertemWege erstellt wurden, aus demSpeicher der Wii- Konsole gelöscht, da sie die Wii-Konsole beschädigen und/oder Fehler in Spielesoftware verursachen können.Wirmöchten darauf hinweisen, dass Nintendo keine Gewährleistung für die Funktionsfähigkeit von unlizensierter Software oder unlizensiertem Zubehör nach diesem oder einem zukünftigen Update des Wii-Menüs gibt. -

Scorpio Charge Texan Seeking with Piracy HOUSTON -A Federal Grand Jury Aug

12 General News Scorpio Charge Texan Seeking With Piracy HOUSTON -A federal grand jury Aug. 30 returned an indictment Seized in what was said to be the Southern district of Texas' first case of alleged copyright violation in the sale of 8- Records track tapes. By IS HOROWITZ Charged was Howard W. Çole of NEW YORK -Scorpio Music Pearland, who allegedly sold copies Distributors has petitioned the U.S. of Linda Ronstadt and Waylon Jen- District Court in Philadelphia to or- nings recordings without author der the return of some 24,000 Bob ization from the copyright owners. Dylan records seized last February Assistant U.S. Attorney Dan Ka- by the FBI as infringing merchan- min says the FBI has 1,146 tapes dise. seized from a booth Cole set up in The bid comes in a reply by the March at the Astrohall to sell tapes Croydon, Pa.. cutout wholesaler to a and citizen band radios at the Hous- civil action filed in court last month ton Livestock Show and Rodeo. by Warner Bros., claiming a three - Two tapes purchased from Cole disk set marketed by Scorpio con- no recording company la- tained unauthorized recordings of displayed bels and were found by scientific Dylan tunes held in Warner's music tests administered by the FBI to be publishing catalogs. copies of original recordings, Kamin At the same time, Scorpio's court TAPE DEPOT -Sound Warehouse, Matteson, fll., displays 8- tracks, cassettes full -face to customer. Selected titles are says. document, filed Tuesday (6), in- pulled from working stock behind the display. -

With Termination of Copyright Grants, Disco Lives

With termination of copyright grants, disco lives Timothy J. Lockhart Willcox Savage © December 24, 2012 Inside Business A little-known provision of the Copyright Act of 1976 (Act) may soon acquire major importance. Under Section 203 of the Act (17 U.S.C. § 203) a copyright assignment or license may, under certain circumstances, be terminated 35 years after being granted. Because the Act became effective on January 1, 1978, the first date on which such termination can be effective is January 1, 2013. As illustrated by the ongoing case of Scorpio Music S.A. v. Willis, No. 3:11-cv-01557-BTM-RBB (S.D. Cal. filed July 14, 2011)—involving disco hits by the Village People—disputes over Section 203 terminations have already begun and will likely increase as more authors become aware of their termination rights. Section 203 permits an author or his or her heirs to terminate the author’s “exclusive or nonexclusive grant of a transfer or license of copyright or any right under a copyright” made on or after January 1, 1978, provided that the termination right is exercised within five years after the end of the 35-year period. If the grant covers the right to publish a work, the termination period begins at the earlier of (a) 35 years after publication under the grant or (b) the end of 40 years after execution of the grant. The right is permanently lost if not exercised within that five-year window. The person(s) exercising the termination right must give proper notice to the grantee or its successor at least two but not more than 10 years before the termination date. -

Adventures of Priscilla Queen of the Desert Music Credits

Music by Guy Gross Music recorded at Trackdown Studios Music Engineer Simon Leadley Performed by Sydney Philharmonic Choir Directed by Antony Walker Soprano Solo by Robyn Dunn Original music published by Mushroom Music Song Clearances Diana Williams Songs I’VE NEVER BEEN TO ME written by Ken Kirsch and Ronald Miller performed by Charlene published by Stone Diamond Music Corp./Jobete Music courtesy Motown Record Company LP GO WEST written by Jacques Morali, Henri Belolo and Victor Willis performed by Village People published by Scorpio Music courtesy BMG/RCA BILLY DON’T BE A HERO written by Mitch Murray and Peter Callander performed by Paper Lace published by Dick James Music Ltd courtesy Castle Communications (Australasia) Ltd. MY BABY LOVES LOVIN’ written by Roger Cook and Roger Greenaway performed by White Plains published by Dick James Music Ltd courtesy The Decca Record Company Ltd. I LOVE THE NIGHTLIFE written by Susan Hutcheson and Alicia Bridges performed by Alicia Bridges published by BMG Music Publishing courtesy Polydor International CAN”T HELP LOVIN’ THAT MAN written by Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein II performed by Trudy Richards published by PolyGram International Publishing Inc. courtesy Capitol Records Inc. E STRANO! AH FORS E LUI written by Guiseppe Verdi performed by Joan Carden and the Sydney Symphony Orchestra courtesy ABC Classics FERNANDO written by Benny Andersson, Bjorn Ulvaeus and Stig Anderson Performed by Abba Published by Union Songs AB Courtesy Sweden Music AB I WILL SURVIVE written by Dino Fekaris and Freddie Perren performed by Gloria Gaynor published by PolyGram International Publishing Inc. and Perren-Vibes Music Inc. -

Download As A

SHIPPING THE OLD MAN ACROSS THE SEA: THE IMPORTATION OF BOOKS IN THE PUBLIC DOMAIN ABROAD MATTHEW H. HARTZLER* When consumers purchase books through sites like Amazon, anony- mous third-party sellers fill the orders. And increasingly, they do so using goods of unknown origin. Sometimes, the sellers send pirated counterfeits; other times, they ship authentic books produced for foreign markets, which are often much cheaper. Provisions of the Copyright Act bar both. Yet when the Supreme Court decided a Thai grad student could import foreign edi- tions of English-language textbooks, it approved of the latter booksellers’ international arbitrage. First sale, the ability to resell a copyrighted work without asking the author for permission, trumps copyright’s importation restrictions. Counterfeits, however, can still be barred at the border. First sale only applies to copies “lawfully made.” The Old Man and the Sea is still under copyright protection in Amer- ica, but it lapsed into the public domain in Canada in 2011. Would a copy printed in another country—one where the work is in the public domain— be considered “lawful”? This Note argues that a copy of The Old Man printed in Canada could not be lawfully shipped across the border to American consumers. And as the first scholarly article to discuss importa- tion of copyrighted works that are in the public domain in other countries, it strives to clarify how and when the Copyright Act deems a work as “law- fully made.” TABLE OF CONTENTS I. INTRODUCTION ..................................................................................... 1008 II. BACKGROUND ....................................................................................... 1014 A. Unauthorized Importation Ban: § 602(a)(1) ............................... -

“Ears 2 Tha Streets” the Bi-Weekly E-Mail Publication Alerting the Music Industry to the Music, News and Issues Making an Impact on the Urban Streets

S.U.R.E. DJ COALITION New York City’s & The Web’s Foremost Vinyl, Digital & MP3 Internet Music Pool “EARS 2 THA STREETS” THE BI-WEEKLY E-MAIL PUBLICATION ALERTING THE MUSIC INDUSTRY TO THE MUSIC, NEWS AND ISSUES MAKING AN IMPACT ON THE URBAN STREETS VOLUME # 8 / ISSUE # 11 / DECEMBER 15 - 31, 2007 NEW & HOT S.U.R.E.SHOTS! AZ – Life On The Line - Koch Mary J Blige – Work That – Geffen Murs – Better Than The Best - Warner Lil KeKe – I’m A G – Universal Motown Wu Tang – Clan – The Heart Gently Weeps - SRC TOP TUNES IN THE BIG APPLE! 50 Cent – I’ll Still Kill - Shady Jeff Redd – Get Into It – Sol Real Mary J Blige – Just Fine - Geffen Alicia Keys – No One (Remix) - J K.A.R. – Kill All Rats Anthem - Koch PRIME CHART MOVERS! J Holiday – Suffocate - Capitol Timbaland – Scream - Interscope Trina – Single Again – Slip N Slide Mike Jones – Drop & Gimme 50 - Warner Erykah Badu – Honey – Universal Motown TOP TURNTABLE ADDS! Sasha Payne – Crush - Snap Don Claudio – Get On Up – Raw Core Black Steele – I Got Ya – Straight Hustle Larenzo – Angel Girl – JD Entertainment Elephant Man – Our World – VP / Bad Boy WORDS FROM THE PUBLISHER – BOBBY E. DAVIS Each year around this time, the labels make a great deal of changes. For many, this joyful time of the year is full of worries, sadness and craziness. I hope and pray that no one on S.U.R.E.’s mailing list experiences any negativity over the upcoming holiday season. With God’s blessings, it will be beautiful for all our associates and readers to enjoy life everyday and especially during the holidays without any problems. -

Scenes from the Copyright Office

Touro Law Review Volume 32 Number 1 Symposium: Billy Joel & the Law Article 7 April 2016 Scenes from the Copyright Office Brian L. Frye Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview Part of the Intellectual Property Law Commons Recommended Citation Frye, Brian L. (2016) "Scenes from the Copyright Office," Touro Law Review: Vol. 32 : No. 1 , Article 7. Available at: https://digitalcommons.tourolaw.edu/lawreview/vol32/iss1/7 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. It has been accepted for inclusion in Touro Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Touro Law Center. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Frye: Scenes from the Copyright Office SCENES FROM THE COPYRIGHT OFFICE Brian L. Frye* In his iconic song, “Scenes from an Italian Restaurant,” Billy Joel uses a series of vignettes to describe an encounter between two former classmates, meeting again after many years.1 The song begins as a ballad as they exchange pleasantries, segues into jazz as they reminisce about high school, shifts to rock as they gossip about the decline and fall of the former king and queen of the prom, then returns to a ballad as they part.2 The genius of the song is that the banality of the vignettes perfectly captures the subjective experience of its protagonists. This essay uses a series of vignettes drawn from Joel’s career to describe his encounters with copyright law. It begins by examining the ownership of the copyright in Joel’s songs.