Rnai Screening Reveals Requirement for Host Cell Secretory Pathway in Infection by Diverse Families of Negative-Strand RNA Viruses

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Gene Expression Data for Gene Ontology

ANALYSIS OF GENE EXPRESSION DATA FOR GENE ONTOLOGY BASED PROTEIN FUNCTION PREDICTION A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science Robert Daniel Macholan May 2011 ANALYSIS OF GENE EXPRESSION DATA FOR GENE ONTOLOGY BASED PROTEIN FUNCTION PREDICTION Robert Daniel Macholan Thesis Approved: Accepted: _______________________________ _______________________________ Advisor Department Chair Dr. Zhong-Hui Duan Dr. Chien-Chung Chan _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the College Dr. Chien-Chung Chan Dr. Chand K. Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Committee Member Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Yingcai Xiao Dr. George R. Newkome _______________________________ Date ii ABSTRACT A tremendous increase in genomic data has encouraged biologists to turn to bioinformatics in order to assist in its interpretation and processing. One of the present challenges that need to be overcome in order to understand this data more completely is the development of a reliable method to accurately predict the function of a protein from its genomic information. This study focuses on developing an effective algorithm for protein function prediction. The algorithm is based on proteins that have similar expression patterns. The similarity of the expression data is determined using a novel measure, the slope matrix. The slope matrix introduces a normalized method for the comparison of expression levels throughout a proteome. The algorithm is tested using real microarray gene expression data. Their functions are characterized using gene ontology annotations. The results of the case study indicate the protein function prediction algorithm developed is comparable to the prediction algorithms that are based on the annotations of homologous proteins. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

4-6 Weeks Old Female C57BL/6 Mice Obtained from Jackson Labs Were Used for Cell Isolation

Methods Mice: 4-6 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice obtained from Jackson labs were used for cell isolation. Female Foxp3-IRES-GFP reporter mice (1), backcrossed to B6/C57 background for 10 generations, were used for the isolation of naïve CD4 and naïve CD8 cells for the RNAseq experiments. The mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facility in the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology and were used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee. Preparation of cells: Subsets of thymocytes were isolated by cell sorting as previously described (2), after cell surface staining using CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD3ε (145- 2C11), CD24 (M1/69) (all from Biolegend). DP cells: CD4+CD8 int/hi; CD4 SP cells: CD4CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo; CD8 SP cells: CD8 int/hi CD4 CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo (Fig S2). Peripheral subsets were isolated after pooling spleen and lymph nodes. T cells were enriched by negative isolation using Dynabeads (Dynabeads untouched mouse T cells, 11413D, Invitrogen). After surface staining for CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD25 (PC61) and CD44 (IM7), naïve CD4+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo and naïve CD8+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo were obtained by sorting (BD FACS Aria). Additionally, for the RNAseq experiments, CD4 and CD8 naïve cells were isolated by sorting T cells from the Foxp3- IRES-GFP mice: CD4+CD62LhiCD25–CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– and CD8+CD62LhiCD25– CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– (antibodies were from Biolegend). In some cases, naïve CD4 cells were cultured in vitro under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions (3, 4). -

Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Metabolites As Mediators of DNA Methylation Reprogramming in Bovine Preimplantation Embryos

Supplementary Materials Tricarboxylic Acid Cycle Metabolites as Mediators of DNA Methylation Reprogramming in Bovine Preimplantation Embryos Figure S1. (A) Total number of cells in fast (FBL) and slow (SBL) blastocysts; (B) Fluorescence intensity for 5-methylcytosine and 5-hydroxymethylcytosine of fast and slow blastocysts of cells from Trophoectoderm (TE) or inner cell mass (ICM). Fluorescence intensity for 5-methylcytosine of cells from the ICM or TE in blastocysts cultured with (C) dimethyl-succinate or (D) dimethyl-α- ketoglutarate. Statistical significance is identified by different letters. Figure S2. Experimental design. Table S1. Selected genes related to metabolism and epigenetic mechanisms from RNA-Seq analysis of bovine blastocysts (slow vs. fast). Genes in blue represent upregulation in slow blastocysts, genes in red represent upregulation in fast blastocysts. log2FoldCh Gene p-value p-Adj ange PDHB −1.425 0.000 0.000 MDH1 −1.206 0.000 0.000 APEX1 −1.193 0.000 0.000 OGDHL −3.417 0.000 0.002 PGK1 −0.942 0.000 0.002 GLS2 1.493 0.000 0.002 AICDA 1.171 0.001 0.005 ACO2 0.693 0.002 0.011 CS −0.660 0.002 0.011 SLC25A1 1.181 0.007 0.032 IDH3A −0.728 0.008 0.035 GSS 1.039 0.013 0.053 TET3 0.662 0.026 0.093 GLUD1 −0.450 0.032 0.108 SDHD −0.619 0.049 0.143 FH −0.547 0.054 0.149 OGDH 0.316 0.133 0.287 ACO1 −0.364 0.141 0.297 SDHC −0.335 0.149 0.311 LIG3 0.338 0.165 0.334 SUCLG −0.332 0.174 0.349 SDHA 0.297 0.210 0.396 SUCLA2 −0.324 0.248 0.439 DNMT1 0.266 0.279 0.486 IDH3B1 −0.269 0.296 0.503 SDHB −0.213 0.339 0.544 DNMT3B 0.181 0.386 0.598 APOBEC1 0.629 0.386 0.598 TDG 0.427 0.398 0.611 IDH3G 0.237 0.468 0.675 NEIL2 0.509 0.572 0.720 IDH2 0.298 0.571 0.720 DNMT3L 1.306 0.590 0.722 GLS 0.120 0.706 0.821 XRCC1 0.108 0.793 0.887 TET1 −0.028 0.879 0.919 DNMT3A 0.029 0.893 0.920 MBD4 −0.056 0.885 0.920 PDHX 0.033 0.890 0.920 SMUG1 0.053 0.936 0.954 TET2 −0.002 0.991 0.991 Table S2. -

Involvement of DPP9 in Gene Fusions in Serous Ovarian Carcinoma

Smebye et al. BMC Cancer (2017) 17:642 DOI 10.1186/s12885-017-3625-6 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Involvement of DPP9 in gene fusions in serous ovarian carcinoma Marianne Lislerud Smebye1,2, Antonio Agostini1,2, Bjarne Johannessen2,3, Jim Thorsen1,2, Ben Davidson4,5, Claes Göran Tropé6, Sverre Heim1,2,5, Rolf Inge Skotheim2,3 and Francesca Micci1,2* Abstract Background: A fusion gene is a hybrid gene consisting of parts from two previously independent genes. Chromosomal rearrangements leading to gene breakage are frequent in high-grade serous ovarian carcinomas and have been reported as a common mechanism for inactivating tumor suppressor genes. However, no fusion genes have been repeatedly reported to be recurrent driver events in ovarian carcinogenesis. We combined genomic and transcriptomic information to identify novel fusion gene candidates and aberrantly expressed genes in ovarian carcinomas. Methods: Examined were 19 previously karyotyped ovarian carcinomas (18 of the serous histotype and one undifferentiated). First, karyotypic aberrations were compared to fusion gene candidates identified by RNA sequencing (RNA-seq). In addition, we used exon-level gene expression microarrays as a screening tool to identify aberrantly expressed genes possibly involved in gene fusion events, and compared the findings to the RNA-seq data. Results: We found a DPP9-PPP6R3 fusion transcript in one tumor showing a matching genomic 11;19-translocation. Another tumor had a rearrangement of DPP9 with PLIN3. Both rearrangements were associated with diminished expression of the 3′ end of DPP9 corresponding to the breakpoints identified by RNA-seq. For the exon-level expression analysis, candidate fusion partner genes were ranked according to deviating expression compared to the median of the sample set. -

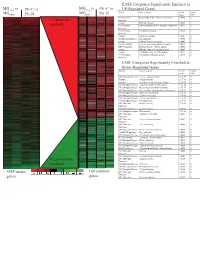

Supplement 1 Microarray Studies

EASE Categories Significantly Enriched in vs MG vs vs MGC4-2 Pt1-C vs C4-2 Pt1-C UP-Regulated Genes MG System Gene Category EASE Global MGRWV Pt1-N RWV Pt1-N Score FDR GO Molecular Extracellular matrix cellular construction 0.0008 0 110 genes up- Function Interpro EGF-like domain 0.0009 0 regulated GO Molecular Oxidoreductase activity\ acting on single dono 0.0015 0 Function GO Molecular Calcium ion binding 0.0018 0 Function Interpro Laminin-G domain 0.0025 0 GO Biological Process Cell Adhesion 0.0045 0 Interpro Collagen Triple helix repeat 0.0047 0 KEGG pathway Complement and coagulation cascades 0.0053 0 KEGG pathway Immune System – Homo sapiens 0.0053 0 Interpro Fibrillar collagen C-terminal domain 0.0062 0 Interpro Calcium-binding EGF-like domain 0.0077 0 GO Molecular Cell adhesion molecule activity 0.0105 0 Function EASE Categories Significantly Enriched in Down-Regulated Genes System Gene Category EASE Global Score FDR GO Biological Process Copper ion homeostasis 2.5E-09 0 Interpro Metallothionein 6.1E-08 0 Interpro Vertebrate metallothionein, Family 1 6.1E-08 0 GO Biological Process Transition metal ion homeostasis 8.5E-08 0 GO Biological Process Heavy metal sensitivity/resistance 1.9E-07 0 GO Biological Process Di-, tri-valent inorganic cation homeostasis 6.3E-07 0 GO Biological Process Metal ion homeostasis 6.3E-07 0 GO Biological Process Cation homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Biological Process Cell ion homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Biological Process Ion homeostasis 2.1E-06 0 GO Molecular Helicase activity 2.3E-06 0 Function GO Biological -

Genetic and Genomic Analysis of Hyperlipidemia, Obesity and Diabetes Using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/Jngj) F2 Mice

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Nutrition Publications and Other Works Nutrition 12-19-2010 Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice Taryn P. Stewart Marshall University Hyoung Y. Kim University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Arnold M. Saxton University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Jung H. Kim Marshall University Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_nutrpubs Part of the Animal Sciences Commons, and the Nutrition Commons Recommended Citation BMC Genomics 2010, 11:713 doi:10.1186/1471-2164-11-713 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Nutrition at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Nutrition Publications and Other Works by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Stewart et al. BMC Genomics 2010, 11:713 http://www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2164/11/713 RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Genetic and genomic analysis of hyperlipidemia, obesity and diabetes using (C57BL/6J × TALLYHO/JngJ) F2 mice Taryn P Stewart1, Hyoung Yon Kim2, Arnold M Saxton3, Jung Han Kim1* Abstract Background: Type 2 diabetes (T2D) is the most common form of diabetes in humans and is closely associated with dyslipidemia and obesity that magnifies the mortality and morbidity related to T2D. The genetic contribution to human T2D and related metabolic disorders is evident, and mostly follows polygenic inheritance. The TALLYHO/ JngJ (TH) mice are a polygenic model for T2D characterized by obesity, hyperinsulinemia, impaired glucose uptake and tolerance, hyperlipidemia, and hyperglycemia. -

Essential Genes and Their Role in Autism Spectrum Disorder

University of Pennsylvania ScholarlyCommons Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations 2017 Essential Genes And Their Role In Autism Spectrum Disorder Xiao Ji University of Pennsylvania, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations Part of the Bioinformatics Commons, and the Genetics Commons Recommended Citation Ji, Xiao, "Essential Genes And Their Role In Autism Spectrum Disorder" (2017). Publicly Accessible Penn Dissertations. 2369. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2369 This paper is posted at ScholarlyCommons. https://repository.upenn.edu/edissertations/2369 For more information, please contact [email protected]. Essential Genes And Their Role In Autism Spectrum Disorder Abstract Essential genes (EGs) play central roles in fundamental cellular processes and are required for the survival of an organism. EGs are enriched for human disease genes and are under strong purifying selection. This intolerance to deleterious mutations, commonly observed haploinsufficiency and the importance of EGs in pre- and postnatal development suggests a possible cumulative effect of deleterious variants in EGs on complex neurodevelopmental disorders. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) is a heterogeneous, highly heritable neurodevelopmental syndrome characterized by impaired social interaction, communication and repetitive behavior. More and more genetic evidence points to a polygenic model of ASD and it is estimated that hundreds of genes contribute to ASD. The central question addressed in this dissertation is whether genes with a strong effect on survival and fitness (i.e. EGs) play a specific oler in ASD risk. I compiled a comprehensive catalog of 3,915 mammalian EGs by combining human orthologs of lethal genes in knockout mice and genes responsible for cell-based essentiality. -

Genome-Wide DNA Methylation and Long-Term Ambient Air Pollution

Lee et al. Clinical Epigenetics (2019) 11:37 https://doi.org/10.1186/s13148-019-0635-z RESEARCH Open Access Genome-wide DNA methylation and long- term ambient air pollution exposure in Korean adults Mi Kyeong Lee1 , Cheng-Jian Xu2,3,4, Megan U. Carnes5, Cody E. Nichols1, James M. Ward1, The BIOS consortium, Sung Ok Kwon6, Sun-Young Kim7*†, Woo Jin Kim6*† and Stephanie J. London1*† Abstract Background: Ambient air pollution is associated with numerous adverse health outcomes, but the underlying mechanisms are not well understood; epigenetic effects including altered DNA methylation could play a role. To evaluate associations of long-term air pollution exposure with DNA methylation in blood, we conducted an epigenome- wide association study in a Korean chronic obstructive pulmonary disease cohort (N = 100 including 60 cases) using Illumina’s Infinium HumanMethylation450K Beadchip. Annual average concentrations of particulate matter ≤ 10 μmin diameter (PM10) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) were estimated at participants’ residential addresses using exposure prediction models. We used robust linear regression to identify differentially methylated probes (DMPs) and two different approaches, DMRcate and comb-p, to identify differentially methylated regions (DMRs). Results: After multiple testing correction (false discovery rate < 0.05), there were 12 DMPs and 27 DMRs associated with PM10 and 45 DMPs and 57 DMRs related to NO2. DMP cg06992688 (OTUB2) and several DMRs were associated with both exposures. Eleven DMPs in relation to NO2 confirmed previous findings in Europeans; the remainder were novel. Methylation levels of 39 DMPs were associated with expression levels of nearby genes in a separate dataset of 3075 individuals. -

Molecular Effects of Isoflavone Supplementation Human Intervention Studies and Quantitative Models for Risk Assessment

Molecular effects of isoflavone supplementation Human intervention studies and quantitative models for risk assessment Vera van der Velpen Thesis committee Promotors Prof. Dr Pieter van ‘t Veer Professor of Nutritional Epidemiology Wageningen University Prof. Dr Evert G. Schouten Emeritus Professor of Epidemiology and Prevention Wageningen University Co-promotors Dr Anouk Geelen Assistant professor, Division of Human Nutrition Wageningen University Dr Lydia A. Afman Assistant professor, Division of Human Nutrition Wageningen University Other members Prof. Dr Jaap Keijer, Wageningen University Dr Hubert P.J.M. Noteborn, Netherlands Food en Consumer Product Safety Authority Prof. Dr Yvonne T. van der Schouw, UMC Utrecht Dr Wendy L. Hall, King’s College London This research was conducted under the auspices of the Graduate School VLAG (Advanced studies in Food Technology, Agrobiotechnology, Nutrition and Health Sciences). Molecular effects of isoflavone supplementation Human intervention studies and quantitative models for risk assessment Vera van der Velpen Thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of doctor at Wageningen University by the authority of the Rector Magnificus Prof. Dr M.J. Kropff, in the presence of the Thesis Committee appointed by the Academic Board to be defended in public on Friday 20 June 2014 at 13.30 p.m. in the Aula. Vera van der Velpen Molecular effects of isoflavone supplementation: Human intervention studies and quantitative models for risk assessment 154 pages PhD thesis, Wageningen University, Wageningen, NL (2014) With references, with summaries in Dutch and English ISBN: 978-94-6173-952-0 ABSTRact Background: Risk assessment can potentially be improved by closely linked experiments in the disciplines of epidemiology and toxicology. -

Aneuploidy: Using Genetic Instability to Preserve a Haploid Genome?

Health Science Campus FINAL APPROVAL OF DISSERTATION Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science (Cancer Biology) Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Submitted by: Ramona Ramdath In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Biomedical Science Examination Committee Signature/Date Major Advisor: David Allison, M.D., Ph.D. Academic James Trempe, Ph.D. Advisory Committee: David Giovanucci, Ph.D. Randall Ruch, Ph.D. Ronald Mellgren, Ph.D. Senior Associate Dean College of Graduate Studies Michael S. Bisesi, Ph.D. Date of Defense: April 10, 2009 Aneuploidy: Using genetic instability to preserve a haploid genome? Ramona Ramdath University of Toledo, Health Science Campus 2009 Dedication I dedicate this dissertation to my grandfather who died of lung cancer two years ago, but who always instilled in us the value and importance of education. And to my mom and sister, both of whom have been pillars of support and stimulating conversations. To my sister, Rehanna, especially- I hope this inspires you to achieve all that you want to in life, academically and otherwise. ii Acknowledgements As we go through these academic journeys, there are so many along the way that make an impact not only on our work, but on our lives as well, and I would like to say a heartfelt thank you to all of those people: My Committee members- Dr. James Trempe, Dr. David Giovanucchi, Dr. Ronald Mellgren and Dr. Randall Ruch for their guidance, suggestions, support and confidence in me. My major advisor- Dr. David Allison, for his constructive criticism and positive reinforcement. -

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary materials Supplementary Table S1: MGNC compound library Ingredien Molecule Caco- Mol ID MW AlogP OB (%) BBB DL FASA- HL t Name Name 2 shengdi MOL012254 campesterol 400.8 7.63 37.58 1.34 0.98 0.7 0.21 20.2 shengdi MOL000519 coniferin 314.4 3.16 31.11 0.42 -0.2 0.3 0.27 74.6 beta- shengdi MOL000359 414.8 8.08 36.91 1.32 0.99 0.8 0.23 20.2 sitosterol pachymic shengdi MOL000289 528.9 6.54 33.63 0.1 -0.6 0.8 0 9.27 acid Poricoic acid shengdi MOL000291 484.7 5.64 30.52 -0.08 -0.9 0.8 0 8.67 B Chrysanthem shengdi MOL004492 585 8.24 38.72 0.51 -1 0.6 0.3 17.5 axanthin 20- shengdi MOL011455 Hexadecano 418.6 1.91 32.7 -0.24 -0.4 0.7 0.29 104 ylingenol huanglian MOL001454 berberine 336.4 3.45 36.86 1.24 0.57 0.8 0.19 6.57 huanglian MOL013352 Obacunone 454.6 2.68 43.29 0.01 -0.4 0.8 0.31 -13 huanglian MOL002894 berberrubine 322.4 3.2 35.74 1.07 0.17 0.7 0.24 6.46 huanglian MOL002897 epiberberine 336.4 3.45 43.09 1.17 0.4 0.8 0.19 6.1 huanglian MOL002903 (R)-Canadine 339.4 3.4 55.37 1.04 0.57 0.8 0.2 6.41 huanglian MOL002904 Berlambine 351.4 2.49 36.68 0.97 0.17 0.8 0.28 7.33 Corchorosid huanglian MOL002907 404.6 1.34 105 -0.91 -1.3 0.8 0.29 6.68 e A_qt Magnogrand huanglian MOL000622 266.4 1.18 63.71 0.02 -0.2 0.2 0.3 3.17 iolide huanglian MOL000762 Palmidin A 510.5 4.52 35.36 -0.38 -1.5 0.7 0.39 33.2 huanglian MOL000785 palmatine 352.4 3.65 64.6 1.33 0.37 0.7 0.13 2.25 huanglian MOL000098 quercetin 302.3 1.5 46.43 0.05 -0.8 0.3 0.38 14.4 huanglian MOL001458 coptisine 320.3 3.25 30.67 1.21 0.32 0.9 0.26 9.33 huanglian MOL002668 Worenine