Effects of Springtails Community on Plant-Growth

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

10) Correlation - Methods

10) Correlation - Methods 10) Correlation – Methods Correlations between structural attributes and arthropod biodiversity were investigated. The results can shed light on the influence of structure and the response of the animals. Using bivariate techniques, the structural descriptors in ten categories were matched against summaries of abundance, richness, diversity, and the abundance of each RTU. NMS vector biplots highlight structural descriptors most strongly correlated with changes in arthropod composition. Mantel tests investigated the strength of the relationship of similarity between trees for structure against the similarity between trees for arthropods. 10.1 Exploring correlations between structure and arthropod biodiversity The effect of crown structure on the trunk and canopy arthropod biodiversity was explored at a tree level. Only information describing each tree was used. No trap or placement level analyses were conducted. The structural descriptors of the tree were considered independent predictors, and tree level arthropod biodiversity descriptors were considered dependent responses. Interpretation of the results must accommodate that several structural descriptors were strongly correlated. For example, mean cone volume corresponds with mean cone surface area. Some descriptors were perfectly correlated. For example, the largest branch airspace was always found in a large branch, and therefore the descriptor of maximum branch airspace for all branches will be the same as the maximum branch airspace for dead branches. Correlation does not equal causation. The correlation of a structural descriptor with any aspect of arthropod biodiversity does necessarily mean the arthropod is responding to that measure. It is possible that the animals are actually responding to cryptic predictors. If these cryptic predictors are themselves correlated with the observed predictor variables, then a potentially misleading predictor-response will be observed. -

Why Are There So Many Exotic Springtails in Australia? a Review

90 (3) · December 2018 pp. 141–156 Why are there so many exotic Springtails in Australia? A review. Penelope Greenslade1, 2 1 Environmental Management, School of School of Health and Life Sciences, Federation University, Ballarat, Victoria 3353, Australia 2 Department of Biology, Australian National University, GPO Box, Australian Capital Territory 0200, Australia E-mail: [email protected] Received 17 October 2018 | Accepted 23 November 2018 Published online at www.soil-organisms.de 1 December 2018 | Printed version 15 December 2018 DOI 10.25674/y9tz-1d49 Abstract Native invertebrate assemblages in Australia are adversely impacted by invasive exotic plants because they are replaced by exotic, invasive invertebrates. The reasons have remained obscure. The different physical, chemical and biotic characteristics of the novel habitat seem to present hostile conditions for native species. This results in empty niches. It seems the different ecologies of exotic invertebrate species may be better adapted to colonise these novel empty niches than native invertebrates. Native faunas of other southern continents that possess a highly endemic fauna, such as South America, South Africa and New Zealand, may have suffered the same impacts from exotic species but insufficient survey data and unreliable and old taxonomy makes this uncertain. Here I attempt to discover what particular characteristics of these novel habitats are hostile to native invertebrates. I chose the Collembola as a target taxon. They are a suitable group because the Australian collembolan fauna consists of a high percentage of endemic taxa, but also exotic, non-native, species. Most exotic Collembola species in Australia appear to have originated from Europe, where they occur at low densities (Fjellberg 1997, 2007). -

Folsomia Candida and the Results of a Ringtest

Toxicity testing with the collembolans Folsomia fimetaria and Folsomia candida and the results of a ringtest P.H. Krogh DMU/AU, Denmark Department of Terrestrial Ecology With contributions from: Mónica João de Barros Amorim, Pilar Andrés, Gabor Bakonyi, Kristin Becker van Slooten, Xavier Domene, Ine Geujin, Nobuhiro Kaneko, Silvio Knäbe, Vladimír Kocí, Jan Lana, Thomas Moser, Juliska Princz, Maike Schaefer, Janeck J. Scott-Fordsmand, Hege Stubberud, Berndt-Michael Wilke August 2008 1 Contents 1 PREFACE 3 2 BIOLOGY AND ECOTOXICOLOGY OF F. FIMETARIA AND F. CANDIDA 4 2.1 INTRODUCTION TO F. FIMETARIA AND F. CANDIDA 4 2.2 COMPARISON OF THE TWO SPECIES 6 2.3 GENETIC VARIABILITY 7 2.4 ALTERNATIVE COLLEMBOLAN TEST SPECIES 8 2.5 DIFFERENCES IN SUSCEPTIBILITY OF THE TWO SPECIES 8 2.6 VARIABILITY IN REPRODUCTION RATES 8 3 TESTING RESULTS OBTAINED AT NERI, 1994 TO 1999 10 3.1 INTRODUCTION 10 3.2 PERFORMANCE 10 3.3 INFLUENCE OF SOIL TYPE 10 3.4 CONCLUSION 11 4 RINGTEST RESULTS 13 4.1 TEST GUIDELINE 13 4.2 PARTICIPANTS 13 4.3 MODEL CHEMICALS 14 4.4 RANGE FINDING 14 4.5 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS 14 4.6 EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN 15 4.7 TEST CONDITIONS 15 4.8 CONTROL MORTALITY 15 4.9 CONTROL REPRODUCTION 16 4.10 VARIABILITY OF TESTING RESULTS 17 4.11 CONCLUSION 18 5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 27 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 29 7 REFERENCES 30 ANNEX 1 PARTICIPANTS 36 ANNEX 2 LABORATORY CODE 38 ANNEX 3 BIBLIOMETRIC STATISTICS 39 ANNEX 4 INTRALABORATORY VARIABILITY 40 ANNEX 5 CONTROL MORTALITY AND REPRODUCTION 42 ANNEX 6 DRAFT TEST GUIDELINE 44 2 1 Preface Collembolans have been used for ecotoxicological testing for about 4 decades now but they have not yet had the privilege to enter into the OECD test guideline programme. -

Millipedes and Centipedes

MILLIPEDES AND CENTIPEDES Integrated Pest Management In and Around the Home sprouting seeds, seedlings, or straw- berries and other ripening fruits in contact with the ground. Sometimes individual millipedes wander from their moist living places into homes, but they usually die quickly because of the dry conditions and lack of food. Occasionally, large (size varies) (size varies) numbers of millipedes migrate, often uphill, as their food supply dwindles or their living places become either Figure 1. Millipede (left); Centipede (right). too wet or too dry. They may fall into swimming pools and drown. Millipedes and centipedes (Fig. 1) are pedes curl up. The three species When disturbed they do not bite, but often seen in and around gardens and found in California are the common some species exude a defensive liquid may be found wandering into homes. millipede, the bulb millipede, and the that can irritate skin or burn the eyes. Unlike insects, which have three greenhouse millipede. clearly defined body sections and Life Cycle three pairs of legs, they have numer- Millipedes may be confused with Adult millipedes overwinter in the ous body segments and numerous wireworms because of their similar soil. Eggs are laid in clutches beneath legs. Like insects, they belong to the shapes. Wireworms, however, are the soil surface. The young grow largest group in the animal kingdom, click beetle larvae, have only three gradually in size, adding segments the arthropods, which have jointed pairs of legs, and stay underneath the and legs as they mature. They mature bodies and legs and no backbone. soil surface. -

Mesofauna at the Soil-Scree Interface in a Deep Karst Environment

diversity Article Mesofauna at the Soil-Scree Interface in a Deep Karst Environment Nikola Jureková 1,* , Natália Raschmanová 1 , Dana Miklisová 2 and L’ubomír Kováˇc 1 1 Department of Zoology, Institute of Biology and Ecology, Faculty of Science, Pavol Jozef Šafárik University in Košice, Šrobárova 2, SK-04180 Košice, Slovakia; [email protected] (N.R.); [email protected] (L’.K.) 2 Institute of Parasitology, Slovak Academy of Sciences, Hlinkova 3, SK-04001 Košice, Slovakia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: The community patterns of Collembola (Hexapoda) were studied at two sites along a microclimatically inversed scree slope in a deep karst valley in the Western Carpathians, Slovakia, in warm and cold periods of the year, respectively. Significantly lower average temperatures in the scree profile were noted at the gorge bottom in both periods, meaning that the site in the lower part of the scree, near the bank of creek, was considerably colder and wetter compared to the warmer and drier site at upper part of the scree slope. Relatively high diversity of Collembola was observed at two fieldwork scree sites, where cold-adapted species, considered climatic relicts, showed considerable abundance. The gorge bottom, with a cold and wet microclimate and high carbon content even in the deeper MSS horizons, provided suitable environmental conditions for numerous psychrophilic and subterranean species. Ecological groups such as trogloxenes and subtroglophiles showed decreasing trends of abundance with depth, in contrast to eutroglophiles and a troglobiont showing an opposite distributional pattern at scree sites in both periods. Our study documented that in terms of soil and Citation: Jureková, N.; subterranean mesofauna, colluvial screes of deep karst gorges represent (1) a transition zone between Raschmanová, N.; Miklisová, D.; the surface and the deep subterranean environment, and (2) important climate change refugia. -

ARTHROPODA Subphylum Hexapoda Protura, Springtails, Diplura, and Insects

NINE Phylum ARTHROPODA SUBPHYLUM HEXAPODA Protura, springtails, Diplura, and insects ROD P. MACFARLANE, PETER A. MADDISON, IAN G. ANDREW, JOCELYN A. BERRY, PETER M. JOHNS, ROBERT J. B. HOARE, MARIE-CLAUDE LARIVIÈRE, PENELOPE GREENSLADE, ROSA C. HENDERSON, COURTenaY N. SMITHERS, RicarDO L. PALMA, JOHN B. WARD, ROBERT L. C. PILGRIM, DaVID R. TOWNS, IAN McLELLAN, DAVID A. J. TEULON, TERRY R. HITCHINGS, VICTOR F. EASTOP, NICHOLAS A. MARTIN, MURRAY J. FLETCHER, MARLON A. W. STUFKENS, PAMELA J. DALE, Daniel BURCKHARDT, THOMAS R. BUCKLEY, STEVEN A. TREWICK defining feature of the Hexapoda, as the name suggests, is six legs. Also, the body comprises a head, thorax, and abdomen. The number A of abdominal segments varies, however; there are only six in the Collembola (springtails), 9–12 in the Protura, and 10 in the Diplura, whereas in all other hexapods there are strictly 11. Insects are now regarded as comprising only those hexapods with 11 abdominal segments. Whereas crustaceans are the dominant group of arthropods in the sea, hexapods prevail on land, in numbers and biomass. Altogether, the Hexapoda constitutes the most diverse group of animals – the estimated number of described species worldwide is just over 900,000, with the beetles (order Coleoptera) comprising more than a third of these. Today, the Hexapoda is considered to contain four classes – the Insecta, and the Protura, Collembola, and Diplura. The latter three classes were formerly allied with the insect orders Archaeognatha (jumping bristletails) and Thysanura (silverfish) as the insect subclass Apterygota (‘wingless’). The Apterygota is now regarded as an artificial assemblage (Bitsch & Bitsch 2000). -

Collembolans Folsomia Fimetaria and Folsomia Candida and the Results of a Ringtest

Toxicity testing with the collembolans Folsomia fimetaria and Folsomia candida and the results of a ringtest Paul Henning Krogh Danmarks Miljøundersøgelser Aarhus Universitet Environmental Project No. 1256 2009 Miljøprojekt The Danish Environmental Protection Agency will, when opportunity offers, publish reports and contributions relating to environmental research and development projects financed via the Danish EPA. Please note that publication does not signify that the contents of the reports necessarily reflect the views of the Danish EPA. The reports are, however, published because the Danish EPA finds that the studies represent a valuable contribution to the debate on environmental policy in Denmark. Contents 1 PREFACE 5 2 BIOLOGY AND ECOTOXICOLOGY OF F. FIMETARIA AND F. CANDIDA 7 2.1 INTRODUCTION TO F. FIMETARIA AND F. CANDIDA 7 2.2 COMPARISON OF THE TWO SPECIES 9 2.3 GENETIC VARIABILITY 10 2.4 ALTERNATIVE COLLEMBOLAN TEST SPECIES 11 2.5 DIFFERENCES IN SUSCEPTIBILITY OF THE TWO SPECIES 11 2.6 VARIABILITY IN REPRODUCTION RATES 11 3 TESTING RESULTS OBTAINED AT NERI, 1994 TO 1999 13 3.1 INTRODUCTION 13 3.2 PERFORMANCE 13 3.3 INFLUENCE OF SOIL TYPE 13 3.4 CONCLUSION 14 4 RINGTEST RESULTS 17 4.1 TEST GUIDELINE 17 4.2 PARTICIPANTS 18 4.3 MODEL CHEMICALS 18 4.4 RANGE FINDING 18 4.5 STATISTICAL ANALYSIS 18 4.6 EXPERIMENTAL DESIGN 19 4.7 TEST CONDITIONS 19 4.8 CONTROL MORTALITY 20 4.9 CONTROL REPRODUCTION 20 4.10 VARIABILITY OF TESTING RESULTS 21 4.11 CONCLUSION 22 5 SUMMARY AND CONCLUSIONS 31 6 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 33 REFERENCES 35 3 4 1 Preface Collembolans have been used for ecotoxicological testing for about four decades now but they have not yet had the privilege to enter into the OECD test guideline programme. -

Millipedes and Centipedes? Millipedes and Centipedes Are Both Arthropods in the Subphylum Myriapoda Meaning Many Legs

A Teacher’s Resource Guide to Millipedes & Centipedes Compiled by Eric Gordon What are millipedes and centipedes? Millipedes and centipedes are both arthropods in the subphylum Myriapoda meaning many legs. Although related to insects or “bugs”, they are not actually insects, which generally have six legs. How can you tell the difference between millipedes and centipedes? Millipedes have two legs per body segment and are typically have a body shaped like a cylinder or rod. Centipedes have one leg per body segment and their bodies are often flat. Do millipedes really have a thousand legs? No. Millipedes do not have a thousand legs nor do all centipedes have a hundred legs despite their names. Most millipedes have from 40-400 legs with the maximum number of legs reaching 750. No centipede has exactly 100 legs (50 pairs) since centipedes always have an odd number of pairs of legs. Most centipedes have from 30- 50 legs with one order of centipedes (Geophilomorpha) always having much more legs reaching up to 350 legs. Why do millipedes and centipedes have so many legs? Millipedes and centipedes are metameric animals, meaning that their body is divided into segments most of which are completely identical. Metamerization is an important phenomenon in evolution and even humans have a remnant of former metamerization in the repeating spinal discs of our backbone. Insects are thought to have evolved from metameric animals after specializing body segments for specific functions such as the head for sensation and the thorax for locomotion. Millipedes and centipedes may be evolutionary relatives to the ancestor of insects and crustaceans. -

Some Aspects of the Ecology of Millipedes (Diplopoda) Thesis

Some Aspects of the Ecology of Millipedes (Diplopoda) Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Monica A. Farfan, B.S. Graduate Program in Evolution, Ecology, and Organismal Biology The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Hans Klompen, Advisor John W. Wenzel Andrew Michel Copyright by Monica A. Farfan 2010 Abstract The focus of this thesis is the ecology of invasive millipedes (Diplopoda) in the family Julidae. This particular group of millipedes are thought to be introduced into North America from Europe and are now widely found in many urban, anthropogenic habitats in the U.S. Why are these animals such effective colonizers and why do they seem to be mostly present in anthropogenic habitats? In a review of the literature addressing the role of millipedes in nutrient cycling, the interactions of millipedes and communities of fungi and bacteria are discussed. The presence of millipedes stimulates fungal growth while fungal hyphae and bacteria positively effect feeding intensity and nutrient assimilation efficiency in millipedes. Millipedes may also utilize enzymes from these organisms. In a continuation of the study of the ecology of the family Julidae, a comparative study was completed on mites associated with millipedes in the family Julidae in eastern North America and the United Kingdom. The goals of this study were: 1. To establish what mites are present on these millipedes in North America 2. To see if this fauna is the same as in Europe 3. To examine host association patterns looking specifically for host or habitat specificity. -

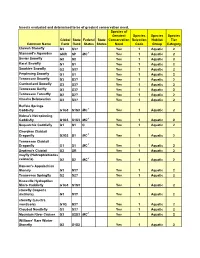

Insects Evaluated and Determined to Be of Greatest Conservation Need

Insects evaluated and determined to be of greatest conservation need. Species of Greatest Species Species Species Global State Federal State Conservation Selection Habitat Tier Common Name Rank Rank Status Status Need Code Group Category Etowah Stonefly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Stannard's Agarodes GNR SP MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Sevier Snowfly G2 S2 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Karst Snowfly G1 S1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Smokies Snowfly G2 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Perplexing Snowfly G1 S1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Snowfly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Cumberland Snowfly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Sallfly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Forestfly G2 S2? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Cheaha Beloneurian G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Buffalo Springs Caddisfly G1G3 S1S3 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Helma's Net-spinning Caddisfly G1G3 S1S3 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Sequatchie Caddisfly G1 S1 C Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Cherokee Clubtail Dragonfly G2G3 S1 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Clubtail Dragonfly G1 S1 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Septima's Clubtail G2 SR Yes 1 Aquatic 2 mayfly (Habrophlebiodes celeteria) G2 S2 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Hanson's Appalachian Stonely G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Tennessee Springfly G2 S2? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Knoxville Hydroptilan Micro Caddisfly G1G3 S1S3 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 stonefly (Isoperla distincta) G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 stonefly (Leuctra monticola) G1Q S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Clouded Needlefly G3 S3? Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Mountain River Cruiser G3 S2S3 MC 1 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Williams' Rare Winter Stonefly G2 S1S2 Yes 1 Aquatic 2 Con't...Insects evaluated and determined to be of greatest conservation need. -

The Role of Heavy Metals in Plant Response to Biotic Stress

molecules Review The Role of Heavy Metals in Plant Response to Biotic Stress Iwona Morkunas 1,*, Agnieszka Wo´zniak 1, Van Chung Mai 1,2, Renata Ruci ´nska-Sobkowiak 3 and Philippe Jeandet 4 1 Department of Plant Physiology, Pozna´nUniversity of Life Sciences, Woły´nska35, 60-637 Pozna´n,Poland; [email protected] (A.W.); [email protected] (V.C.M.) 2 Department of Plant Physiology, Vinh University, Le Duan 182, Vinh City, Vietnam 3 Department of Plant Ecophysiology, Adam Mickiewicz University, Umultowska 89, 61-614 Pozna´n,Poland; [email protected] 4 Research Unit “Induced Resistance and Plant Bioprotection”, UPRES EA 4707, Department of Biology and Biochemistry, Faculty of Sciences, University of Reims, P.O. Box 1039, 02 51687 Reims CEDEX, France; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +48-61-846-6040; Fax: +48-61-848-7179 Received: 25 August 2018; Accepted: 8 September 2018; Published: 11 September 2018 Abstract: The present review discusses the impact of heavy metals on the growth of plants at different concentrations, paying particular attention to the hormesis effect. Within the past decade, study of the hormesis phenomenon has generated considerable interest because it was considered not only in the framework of plant growth stimulation but also as an adaptive response of plants to a low level of stress which in turn can play an important role in their responses to other stress factors. In this review, we focused on the defence mechanisms of plants as a response to different metal ion doses and during the crosstalk between metal ions and biotic stressors such as insects and pathogenic fungi. -

Collembola and Plant Pathogenic, Antagonistic and Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi: a Review

Bulletin of Insectology 71 (1): 71-76, 2018 ISSN 1721-8861 Collembola and plant pathogenic, antagonistic and arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi: a review 1 2 Gloria INNOCENTI , Maria Agnese SABATINI 1Department of Agricultural and Food Sciences, University of Bologna, Italy 2Department of Life Sciences, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Modena, Italy Abstract The review focuses on interactions between plant pathogenic, antagonistic, arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and Collembola to ex- plore the role of these arthropods in the control of plant diseases caused by soil borne fungal pathogens. Approximately forty years ago, the plant pathologist Elroy A. Curl and his co-workers of Auburn University (Alabama, USA) suggested for the first time a role of Collembola in plant disease control. The beneficial effect of springtails for plant health have been confirmed by several subsequent studies with different collembolan and fungal species. Collembola have been found to feed preferably on pathogenic rather than on antagonistic or arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) fungal propagules, thus springtails can reduce the inocu- lum of pathogens without counteracting the activity of fungi beneficial for plant growth and health. Fungal characteristics that may affect the grazing activity of Collembola are also examined. Key words: springtails, soil fungi, plant disease control. Introduction and Thalassaphorura encarpata (Denis) (= Onychiurus encarpatus), the two prevalent Collembola species in Collembola are among the most abundant groups of soil Alabama soils, significantly reduced colony growth of mesofauna; they range in size between 0.2 and 2 mm the plant pathogenic fungi Rhizoctonia solani Khun, Fu- (Anderson, 1988; Hopkin, 1997). The geographical sarium oxysporum Schlect. f. sp. vasinfectum (Atk.) range of Collembola is enormous, as they live in all Snyder et Hansen, Macrophomina phaseolina (Tassi) climatic environments from the Arctic and Antarctic to Goid., and Verticillium dahliae Kleb., separately cul- tropical areas (Tebbe et al., 2006).