How Time Flies When You're Israeli on the One Hand the Region Has Experienced a Sort of Baby Boom

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Humanitarian Monitor CAP Occupied Palestinian Territory Number 17 September 2007

The Humanitarian Monitor CAP occupied Palestinian territory Number 17 September 2007 Overview- Key Issues Table of Contents Update on Continued Closure of Gaza Key Issues 1 - 2 Crossings Regional Focus 3 Access and Crossings Rafah and Karni crossings remain closed after more than threemonths. Protection of Civilians 4 - 5 The movement of goods via Gaza border crossings significantly Child Protection 6-7 declined in September compared to previous months. The average Violence & Private 8-9 of 106 truckloads per day that was recorded between 19 June and Property 13 September has dropped to approximately 50 truckloads per day 10 - 11 since mid-September. Sufa crossing (usually opened 5 days a week) Access was closed for 16 days in September, including 8 days for Israeli Socio-economic 12 - 13 holidays, while Kerem Shalom was open only 14 days throughout Conditions the month. The Israeli Civil Liaison Administration reported that the Health 14 - 15 reduction of working hours was due to the Muslim holy month Food Security & 16 - 18 of Ramadan, Jewish holidays and more importantly attacks on the Agriculture crossings by Palestinian militants from inside Gaza. Water & Sanitation 19 Impact of Closure Education 20 As a result of the increased restrictions on Gaza border crossings, The Response 21 - 22 an increasing number of food items – including fruits, fresh meat and fish, frozen meat, frozen vegetables, chicken, powdered milk, dairy Sources & End Notes 23 - 26 products, beverages and cooking oil – are experiencing shortages on the local market. The World Food Programme (WFP) has also reported significant increases in the costs of these items, due to supply, paid for by deductions from overdue Palestinian tax increases in prices on the global market as well as due to restrictions revenues that Israel withholds. -

Protection of Civilians Weekly Report

U N I TOCHA E D Weekly N A Report: T I O 14N MarchS – 20 March 2007 N A T I O N S| 1 U N I E S OFFICE FOR THE COORDINATION OF HUMANITARIAN AFFAIRS P.O. Box 38712, East Jerusalem, Phone: (+972) 2-582 9962 / 582 5853, Fax: (+972) 2-582 5841 [email protected], www.ochaopt.org Protection of Civilians Weekly Report 14 March – 20 March 2007 Of note this week An UNRWA convoy carrying the Director of UNRWA Operations in Gaza was attacked by a group of armed masked gunmen in the northern Gaza Strip. The convoy escaped unharmed despite numerous shots being fired at the vehicle. Gaza Strip − A Palestinian sniper shot and injured a civilian Israeli utility worker in the Nahal Oz area. The military wing of Hamas claimed responsibility. Nine homemade rockets, one of which detonated inside the Gaza Strip, and two mortar shells were fired by Palestinians throughout the week towards Israel. − Four Israeli military boats opened fire and rounded up 14 Palestinian fishing boats in Rafah and forced them to sail towards deeper waters. IDF vessels tied the boats and ordered the fishermen to jump in the water and swim individually towards the military ships. A total of 54 Palestinian fishermen were interrogated before later being released while two others were arrested. − Seven Palestinians were killed this week as a result of internal violence including an eight year-old girl caught in crossfire during a family dispute. − Eight days have passed since the BBC's reporter was abducted in Gaza City. -

Gaza CRISIS)P H C S Ti P P I U

United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs occupied Palestinian territory Zikim e Karmiya s n e o il Z P m A g l in a AGCCESSA ANDZ AMOV EMENTSTRI (GAZA CRISIS)P h c s ti P P i u F a ¥ SEPTEMBER 2014 o nA P N .5 F 1 Yad Mordekhai EREZ CROSSING (BEIT HANOUN) occupied Palestinian territory: ID a As-Siafa OPEN, six days (daytime) a B?week4 for B?3the4 movement d Governorates e e of international workers and limited number of y h s a b R authorized Palestinians including aid workers, medical, P r 2 e A humanitarian cases, businessmen and aid workers. Jenin d 1 e 0 Netiv ha-Asara P c 2 P Tubas r Tulkarm r fo e S P Al Attarta Temporary Wastewater P n b Treatment Lagoons Qalqiliya Nablus Erez Crossing E Ghaboon m Hai Al Amal r Fado's 4 e B? (Beit Hanoun) Salfit t e P P v i Al Qaraya al Badawiya i v P! W e s t R n m (Umm An-Naser) n i o » B a n k a North Gaza º Al Jam'ia ¹¹ M E D I TER RAN EAN Hatabiyya Ramallah da Jericho d L N n r n r KJ S E A ee o Beit Lahia D P o o J g Wastewater Ed t Al Salateen Beit Lahiya h 5 Al Kur'a J a 9 P l D n Treatment Plant D D D D 9 ) D s As Sultan D 1 2 El Khamsa D " Sa D e J D D l i D 0 D s i D D 0 D D d D D m 2 9 Abedl Hamaid D D r D D l D D o s D D a t D D c Jerusalem D D c n P a D D c h D D i t D D s e P! D D A u P 0 D D D e D D D a l m d D D o i t D D l i " D D n . -

The Tunnels in Gaza February 2015 the Tunnels in Gaza Testimony Before the UN Commission of Inquiry on the 2014 Gaza Conflict Dr

Dr. Eado Hecht 1 The Tunnels in Gaza February 2015 The Tunnels in Gaza Testimony before the UN Commission of Inquiry on the 2014 Gaza Conflict Dr. Eado Hecht The list of questions is a bit repetitive so I have decided to answer not directly to each question but in a comprehensive topical manner. After that I will answer specifically a few of the questions that deserve special emphasis. At the end of the text is an appendix of photographs, diagrams and maps. Sources of Information 1. Access to information on the tunnels is limited. 2. I am an independent academic researcher and I do not have access to information that is not in the public domain. All the information is based on what I have gleaned from unclassified sources that have appeared in the public media over the years – listing them is impossible. 3. The accurate details of the exact location and layout of all the tunnels are known only by the Hamas and partially by Israeli intelligence services and the Israeli commanders who fought in Gaza last summer. 4. Hamas, in order not to reveal its secrets to the Israelis, has not released almost any information on the tunnels themselves except in the form of psychological warfare intended to terrorize Israeli civilians or eulogize its "victory" for the Palestinians: the messages being – the Israelis did not get all the tunnels and we are digging more and see how sophisticated our tunnel- digging operation is. These are carefully sanitized so as not to reveal information on locations or numbers. -

Shelter 2014 A3 V1 Majed.Pdf (English)

GAZA STRIP: Geographic distribution of shelters 21 July 2014 ¥ 3km buffer Zikim a 162km2 (44% of GaKazrmaiya area) 100,000 poeple internally displaced e Estimated pop. of 300,000 B?4 84,000 taking shelter in UNRWA schools S Yad Mordekhai n F As-Siafa B?4 B?34 Governorate # of IDPs a ID y d e e e h b s a R Netiv ha-Asara Gaza 3 2,401 l- n d A e a c Erez Crossing KhanYunis 9 ,900 r Al Qaraya al Badawiya (Beit Hanoun) r (Umm An-Naser) fo 4 º» r h ¹ a n 1 al n Middle 7 ,200 S ee 0 l-D e E 2 E t Beit Lahiya 'Izbat Beit Hanoun a t i k k y E a e l- j S North 2 1,986 l B lo l- i a a A m h F a - 34 i u r l B? J A 5! 5! 5! d L t 'Arab Maslakh Madinat al 'Awda i S w Rafah 1 2,717 ta 5! Beit Lahiya r af 5! ! ee g 5! S 5 az Ash Shati' Camp l- 5! W Beit Hanoun e A !5! Al- n 5!5! 5 lil 5!5! Al-q ka ha i uds ek K 5! l-S Grand Total 8 4,204 M h 5!Jabalia A s 5!5! Jabalia Camp i 5!5! D S !x 5!5!5! a a r le a d h Source of data: UNRWA F o m n a 5!5! a r a K J l- a E m l a a l A n b 5! a 5!de Q 5! l l- d N A Gaza e as e e h r s City a R l- A 5!5! 5! 5! s d ! Mefalsim u 5! Q ! 5! l- 5 A 5! A l- M o n a t 232 kk a B? e r l-S A Kfar Aza d a o R l ta s a o C Sa'ad Al Mughraqa arim Nitz ni - (Abu Middein) Kar ka ek n ú S ú 5! e b l- B a A r tt Juhor ad Dik a a m h K O l- ú A ú Alumim An Nuseirat Shuva Camp 5! 5! Zimrat B?25 5! 5! 5! I S R A E L n e e 5! Kfar Maimon D a 5! - k Tushiya l k Al Bureij Camp E e Az Zawayda h S la l- a A S 5! Be'eri !x 5! Deir al Balah Al Maghazi Shokeda Camp 5! 5! Deir al Balah 5!5! Camp Al Musaddar d a o f R la k l a o ta h o 232 -

The Bedouin Population in the Negev

T The Since the establishment of the State of Israel, the Bedouins h in the Negev have rarely been included in the Israeli public e discourse, even though they comprise around one-fourth B Bedouin e of the Negev’s population. Recently, however, political, d o economic and social changes have raised public awareness u i of this population group, as have the efforts to resolve the n TThehe BBedouinedouin PPopulationopulation status of the unrecognized Bedouin villages in the Negev, P Population o primarily through the Goldberg and Prawer Committees. p u These changing trends have exposed major shortcomings l a in information, facts and figures regarding the Arab- t i iinn tthehe NNegevegev o Bedouins in the Negev. The objective of this publication n The Abraham Fund Initiatives is to fill in this missing information and to portray a i in the n Building a Shared Future for Israel’s comprehensive picture of this population group. t Jewish and Arab Citizens h The first section, written by Arik Rudnitzky, describes e The Abraham Fund Initiatives is a non- the social, demographic and economic characteristics of N Negev profit organization that has been working e Bedouin society in the Negev and compares these to the g since 1989 to promote coexistence and Jewish population and the general Arab population in e equality among Israel’s Jewish and Arab v Israel. citizens. Named for the common ancestor of both Jews and Arabs, The Abraham In the second section, Dr. Thabet Abu Ras discusses social Fund Initiatives advances a cohesive, and demographic attributes in the context of government secure and just Israeli society by policy toward the Bedouin population with respect to promoting policies based on innovative economics, politics, land and settlement, decisive rulings social models, and by conducting large- of the High Court of Justice concerning the Bedouins and scale social change initiatives, advocacy the new political awakening in Bedouin society. -

News of the Israeli-Palestinian Confrontation April 22-29, 2008

Intelligence and Terrorism Information Center Israel Intelligence Heritage and Commemoration Center News of the Israeli-Palestinian Confrontation April 22-29, 2008 Direct hit on a house in Sderot, April 29 The scene of the attack at the Nitzanei Shalom (Photo Zeev Tractman, courtesy of Din industrial area, near Tulkarm (Photo courtesy Veheshbon Communications, Sderot, of ZAKA, April 25). April 29). Overview The main terrorist event this past week was the shooting attack at the Nitzanei Shalom industrial area, near Tulkarm, in which two Israeli civilians were killed. It was another example of terrorist attacks against sites where joint Israeli-Palestinian economic activities are carried out, a clear attempt to damage the interests of the Palestinian people. The high level of rocket fire from the Gaza Strip continued and the IDF continued its counterterrorist activities. Hamas announced that an agreement had been reached in principle with Egypt regarding a gradual lull in the fighting (“Gaza first”) which would later be extended to the West Bank. Hamas regards taking such a step as a means of having the crossings 2 opened on its own terms, and has threatened an escalation in the violence such a lull is not achieved. In the meantime Hamas continues its media campaign to represent the situation in the Gaza Strip as on the brink of collapse, while permitting and even initiating a worsening fuel crisis to back up their campaign. Important Events High level of rocket fire continues Rocket fire into Israel continued during the past week at a relatively high, with 34 identified rocket hits. In addition, 42 mortar shells were fired. -

2014 Gaza War Assessment: the New Face of Conflict

2014 Gaza War Assessment: The New Face of Conflict A report by the JINSA-commissioned Gaza Conflict Task Force March 2015 — Task Force Members, Advisors, and JINSA Staff — Task Force Members* General Charles Wald, USAF (ret.), Task Force Chair Former Deputy Commander of United States European Command Lieutenant General William B. Caldwell IV, USA (ret.) Former Commander, U.S. Army North Lieutenant General Richard Natonski, USMC (ret.) Former Commander of U.S. Marine Corps Forces Command Major General Rick Devereaux, USAF (ret.) Former Director of Operational Planning, Policy, and Strategy - Headquarters Air Force Major General Mike Jones, USA (ret.) Former Chief of Staff, U.S. Central Command * Previous organizational affiliation shown for identification purposes only; no endorsement by the organization implied. Advisors Professor Eliot Cohen Professor of Strategic Studies, Paul H. Nitze School of Advanced International Studies, Johns Hopkins University Lieutenant Colonel Geoffrey Corn, USA (ret.) Presidential Research Professor of Law, South Texas College of Law, Houston JINSA Staff Dr. Michael Makovsky Chief Executive Officer Dr. Benjamin Runkle Director of Programs Jonathan Ruhe Associate Director, Gemunder Center for Defense and Strategy Maayan Roitfarb Programs Associate Ashton Kunkle Gemunder Center Research Assistant . — Table of Contents — 2014 GAZA WAR ASSESSMENT: Executive Summary I. Introduction 7 II. Overview of 2014 Gaza War 8 A. Background B. Causes of Conflict C. Strategies and Concepts of Operations D. Summary of Events -

Table of Contents

Table of Contents Page V. The Threat to Israel’s Civilian Population and Israel’s Civil Defense Measures ............106 A. Life under the Threat of Terrorist Rocket Fire and Cross-Border Tunnel Attacks .................................................................................................................106 B. Israel’s Civil Defence Measures against Rocket and Mortar Attacks .................107 1. Passive Defence Measures .......................................................................107 2. Active Defence Measures (the Iron Dome System) ................................111 C. Harm Caused to Israel’s Civilian Population by Rocket and Mortar Attacks .................................................................................................................112 1. Civilian Deaths and Injuries.....................................................................112 2. Effects on Children, Teenagers and College Students .............................118 3. Effect on the Elderly and People with Disabilities ..................................121 4. Internal Displacement ..............................................................................122 5. Psychological Damage .............................................................................125 6. Economic Damage ...................................................................................132 D. Conclusion ...........................................................................................................136 i V. The Threat to Israel’s Civilian Population -

Curriculum Vitae Gideon Rahat

1 CURRICULUM VITAE GIDEON RAHAT Updated: August 2018 HIGHER EDUCATION 1991 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Political Science, BA 1993 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Political Science, MA 2001 The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, Political Science, PhD; Supervisor: Prof. Emanuel Gutmann 2002 Stanford University, Hoover Institution, postdoctoral studies; Host: George P. Shultz (U.S. Secretary of State 1982-1989) APPOINTMENTS AT THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY 1991 - 2001 Teaching Assistant, Faculty of Social Sciences, Dept. of Political Science 2002 - 2008 Lecturer, Faculty of Social Sciences, Dept. of Political Science 2008 - 2010 Senior Lecturer, Faculty of Social Sciences, Dept. of Political Science 2010 - Assistant Professor, Faculty of Social Sciences, Dept. of Political Science 2013 Gersten Family Chair in Political Science ADDITIONAL FUNCTIONS/TASKS AT THE HEBREW UNIVERSITY (last five years) 2008 - 2014 BA advisor Member of the departmental teaching committee and scholarship committee 2008 - 2013 Academic Head of the Israeli Society and Politics MA Program, Rothberg International School 2016 - Department representative at the Library Committee 2 SERVICE IN OTHER ACADEMIC AND RESEARCH INSTITUTIONS 1994 - 1996 Israel Democracy Institute, Research Assistant 1996 - 2001 Israel Democracy Institute, Research Fellow 2001 - 2002 Hoover Institution, Stanford University, Visiting Fellow 2001 Department of Political Science, Stanford University, Lecturer 2007-2008 Department of Political Science and the Center for the Study of Democracy, University -

Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary

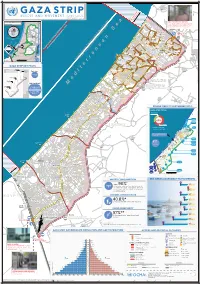

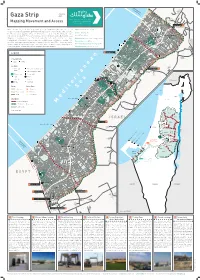

Zikim Karmiya No Fishing Zone 1.5 nautical miles Yad Mordekhai January Gaza Strip 2020 As-Siafa Mapping Movement and Access Netiv Ha'asara Temporary Ar-Rasheed Wastewater Treatment Lagoons Sources: OCHA, Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics of Statistics Bureau Central OCHA, Palestinian Sources: Erez Crossing 1 Al-Qarya Beit Hanoun Al-Badawiya (Umm An-Naser) Erez What is known today as the Gaza Strip, originally a region in Mandatory Palestine, was created Width 5.7-12.5 km / 3.5 – 7.7 mi through the armistice agreements between Israel and Egypt in 1949. From that time until 1967, North Gaza Length ~40 km / 24.8 mi Al- Karama As-Sekka the Strip was under Egyptian control, cut off from Israel as well as the West Bank, which was Izbat Beit Hanoun al-Jaker Road Area 365 km2 / 141 m2 Beit Hanoun under Jordanian rule. In 1967, the connection was renewed when both the West Bank and the Gaza Madinat Beit Lahia Al-'Awda Strip were occupied by Israel. The 1993 Oslo Accords define Gaza and the West Bank as a single Sheikh Zayed Beit Hanoun Population 1,943,398 • 48% Under age 17 July 2019 Industrial Zone Ash-Shati Housing Project Jabalia Sderot territorial unit within which freedom of movement would be permitted. However, starting in the camp al-Wazeer Unemployment rate 47% 2019 Q2 Jabalia Camp Khalil early 90s, Israel began a gradual process of closing off the Strip; since 2007, it has enforced a full Ash-Sheikh closure, forbidding exit and entry except in rare cases. Israel continues to control many aspects of Percentage of population receiving aid 80% An-Naser Radwan Salah Ad-Deen 2 life in Gaza, most of its land crossings, its territorial waters and airspace. -

Israeli Population in the West Bank and East Jerusalem

Name Population East Jerusalem Afula Ramot Allon 46,140 Pisgat Ze'ev 41,930 Gillo 30,900 Israeli Population in the West Bank Neve Ya'akov 22,350 Har Homa 20,660 East Talpiyyot 17,202 and East Jerusalem Ramat Shlomo 14,770 Um French Hill 8,620 el-Fahm Giv'at Ha-Mivtar 6,744 Maalot Dafna 4,000 Beit She'an Jewish Quarter 3,020 Total (East Jerusalem) 216,336 Hinanit Jenin West Bank Modi'in Illit 70,081 Beitar Illit 54,557 Ma'ale Adumim 37,817 Ariel 19,626 Giv'at Ze'ev 17,323 Efrata 9,116 Oranit 8,655 Alfei Menashe 7,801 Kochav Ya'akov 7,687 Karnei Shomron 7,369 Kiryat Arba 7,339 Beit El 6,101 Sha'arei Tikva 5,921 Geva Binyamin 5,409 Mediterranean Netanya Tulkarm Beit Arie 4,955 Kedumim 4,481 Kfar Adumim 4,381 Sea Avnei Hefetz West Bank Eli 4,281 Talmon 4,058 Har Adar 4,058 Shilo 3,988 Sal'it Elkana 3,884 Nablus Elon More Tko'a 3,750 Ofra 3,607 Kedumim Immanuel 3,440 Tzofim Alon Shvut 3,213 Bracha Hashmonaim 2,820 Herzliya Kfar Saba Qalqiliya Kefar Haoranim 2,708 Alfei Menashe Yitzhar Mevo Horon 2,589 Immanuel Itamar El`azar 2,571 Ma'ale Shomron Yakir Bracha 2,468 Ganne Modi'in 2,445 Oranit Mizpe Yericho 2,394 Etz Efraim Revava Kfar Tapuah Revava 2,389 Sha'arei Tikva Neve Daniel 2,370 Elkana Barqan Ariel Etz Efraim 2,204 Tzofim 2,188 Petakh Tikva Nokdim 2,160 Alei Zahav Eli Ma'ale Efraim Alei Zahav 2,133 Tel Aviv Padu'el Yakir 2,056 Shilo Kochav Ha'shachar 2,053 Beit Arie Elon More 1,912 Psagot 1,848 Avnei Hefetz 1,836 Halamish Barqan 1,825 Na'ale 1,804 Padu'el 1,746 Rishon le-Tsiyon Nili 1,597 Nili Keidar 1,590 Lod Kochav Ha'shachar Har Gilo