Fossils of a Dream

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contenido Estrenos Mexicanos

Contenido estrenos mexicanos ............................................................................120 programas especiales mexicanos .................................. 122 Foro de los Pueblos Indígenas 2019 .......................................... 122 Programa Exilio Español ....................................................................... 123 introducción ...........................................................................................................4 Programa Luis Buñuel ............................................................................. 128 Presentación ............................................................................................................... 5 El Día Después ................................................................................................ 132 ¡Bienvenidos a Morelia! ................................................................................... 7 Feratum Film Festival .............................................................................. 134 Mensaje de la Secretaría de Cultura ....................................................8 ......... 10 Mensaje del Instituto Mexicano de Cinematografía funciones especiales mexicanas .......................................137 17° Festival Internacional de Cine de Morelia ............................11 programas especiales internacionales................148 ...........................................................................................................................12 jurados Programa Agnès Varda ...........................................................................148 -

Depaul Animation Zine #1

Conditioner // Shane Beam D i e F l u c h t / / C a r t e r B o y c e 2 0 1 6 S t u d e n t A c a d e m y A w a r d B r o n z e M e d a l 243 South Wabash Avenue Chicago, IL 60604 #1 zine a z i n e e x p l o r i n g t h e A n i m a t i o n C u l t u r e a t D e P a u l U n i v e r s i t y in Chicago R a n k e d t h e # 1 0 A n i m a t i o n M F A P r o g r a m a n d # 1 4 A n i m a t i o n P r o g r a m i n t h e U . S . b y A n i m a t i o n C a r e e r R e v i e w i n 2 0 1 8 D e P a u l h a s 1 3 f u l l - t i m e A n i m a t i o n p r o f e s s o r s , o n e o f t h e l a r g e s t f u l l - t i m e A n i m a t i o n f a c u l t i e s i n t h e U S , w i t h e x p e r t i s e i n t r a d i t i o n a l c h a r a c t e r a n i m a t i o n , 3 D , s t o r y b o a r d i n g , g a m e a r t , s t o p m o t i o n , c h r a c t e r d e s i g n , e x p e r i m e n t a l , a n d m o t i o n g r a p h i c s . -

The Quay Brothers: Choreographed Chiaroscuro, Enigmatic and Sublime Author(S): Suzanne H

The Quay Brothers: Choreographed Chiaroscuro, Enigmatic and Sublime Author(s): Suzanne H. Buchan Source: Film Quarterly, Vol. 51, No. 3 (Spring, 1998), pp. 2-15 Published by: University of California Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1213598 Accessed: 04/04/2010 08:30 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=ucal. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Film Quarterly. http://www.jstor.org The Quay Brothers Since the early 1980s, animation has received increasing attention from cinema and television pro- grammers and is gradually being in- corporated as a viable genre in film studies. -

Surrealist Sources of Eastern European Animation Film

BALTIC SCREEN MEDIA REVIEW 2013 / VOLUME 1 / ARTICLE Article Surrealist Sources of Eastern European Animation Film ÜLO PIKKOV, Estonian Academy of Arts; email: [email protected] 28 DOI: 10.1515/bsmr-2015-0003 BALTIC SCREEN MEDIA REVIEW 2013 / VOLUME 1 / ARTICLE ABSTRACT This article investigates the relationship between surreal- ism and animation fi lm, attempting to establish the char- acteristic features of surrealist animation fi lm and to deter- mine an approach for identifying them. Drawing on the interviews conducted during the research, I will also strive to chart the terrain of contemporary surrealist animation fi lm and its authors, most of who work in Eastern Europe. My principal aim is to establish why surrealism enjoyed such relevance and vitality in post-World War II Eastern Europe. I will conclude that the popularity of surrealist animation fi lm in Eastern Europe can be seen as a continu- ation of a tradition (Prague was an important centre of surrealism during the interwar period), as well as an act of protest against the socialist realist paradigm of the Soviet period. INTRODUCTION ing also in sight the spatiotemporal context Surrealism in animation fi lm has been of production. an under-researched fi eld. While several It must be established from the out- monographs have been written on authors set that there are many ways to understand whose work is related to surrealism (Jan and interpret the notion of “surrealist ani- Švankmajer, Brothers Quay, Priit Pärn, Raoul mation fi lm”. In everyday use, “surreal” often Servais and many others), no broader stud- stands for something obscure and incom- ies on the matter exist. -

A Film by the Quay Brothers

A FILM BY THE QUAY BROTHERS A ZEITGEIST FILMS RELEASE A FILM BY THE QUAY BROTHERS THE PIANO TUNER OF EARTHQUAKES is the breathtakingly beautiful and long-awaited second feature from the Quay Brothers. On the eve of her wedding, the beautiful opera singer Malvina is mysteriously killed and abducted by a malevolent Dr. Droz. Felisberto, an innocent piano tuner, is summoned to Droz’s secluded villa to service his strange musical automatons. Little by little Felisberto learns of the doctor’s plans to stage a “diabolical opera” and of Malvina’s fate. He secretly conspires to rescue her, only to become trapped himself in the web of Droz’s perverse universe... Starring Amira Casar (Catherine Breillat’s ANATOMY OF HELL), Assumpta Serna (Pedro Almodovar’s MATADOR), Cesar Sarachu (the Quays’ INSTITUTE BENJAMENTA) and Gottfried John (Fassbinder’s MARRIAGE OF MARIA BRAUN). THE QUAY BROTHERS The extraordinary Quay Brothers are two of the world’s most original filmmakers. Identical twins who were born in Pennsylvania in 1947, Stephen and Timothy Quay studied illustration in Philadelphia before going on to the Royal College of Art in London, where they started to make animated shorts in the 1970s. They have lived in London ever since, making their unique and innovative films under the aegis of Koninck Studios. Influenced by a tradition of Eastern European animation, the Quays display a passion for detail, a breathtaking command of color and texture, and an uncanny use of focus and camera movement that make their films unique and instantly recognizable. Best known for their classic 1986 film STREET OF CROCODILES, which filmmaker Terry Gilliam recently selected as one of the ten best animated films of all time, they are masters of miniaturization and on their tiny sets have created an unforgettable world, suggestive of a landscape of long-repressed childhood dreams. -

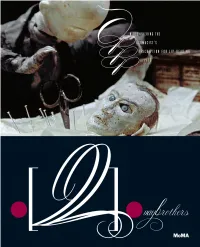

Quaybrothers PREVIEW.Pdf

contents 6 Foreword Glenn D. Lowry 8 Acknowledgments 10 THE MANIC DEPARTMENT STORE New Perspectives on the Quay Brothers Ron Magliozzi 16 THOSE WHO DESIRE WITHOUT END Animation as “Bachelor Machine” Edwin Carels 21 O N DECIPHERING THE PHARMACIST’S PRESCRIPTION FOR LIP-READING PUPPETS A project by the Quay Brothers 28 PlATES 62 Works by the Quay Brothers 63 Selected Bibliography 64 Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art The book also contains a project by the Quay Brothers on the front and back inside covers. Ron Magliozzi t is gratifying to report, right at the start, that the As illustrators, stage designers, and film- The twins’ “facility for drawing”6 was encouraged by reputed inaccessibility of the Quay Brothers’ work is a makers in a range of genres, the Quays have their family. At home, snowy pastoral landscapes of a Imyth. The challenge of deciphering meaning and narra- penetrated many fields of visual expression red barn at different distances were hung side by side, tive in the roughly thirty theatrical shorts and two features for a number of different audiences, from coincidentally suggesting a cinema tracking shot. Stark that the filmmakers have produced since 1979 is real avant-garde cinema and opera to publication countryside landscapes dotted with trees appeared indeed, a characteristic of their work that they adopted art and television advertising. Looking at commonly in their youthful drawings, often with ele- on principle when they were still students. Interpreters of their artistic endeavors as a whole, in the ments of telling human interest, as in Bicycle Course for their stop-motion puppet films, such as the defining Street context of fresh biographical information and Aspiring Amputees (1969) and Fantasy-Penalty for of Crocodiles (1986), have described them as alchemists, new evidence of their creativity, provides Missed Goal (c.1968). -

Edwin Carels Spaces of Wonder: Animation and Museology

Edwin Carels Spaces of Wonder: Animation and Museology "Space is now not just where things happen; things make space happen." Brian O'Doherty: Inside the White Cube – The Ideology of the Gallery Space, University of California Press, Berkeley, i 1999, page 39 The days that animation was the guilty pleasure of a limited group of cinephiles and discreet art devotees are over. Finally? What is at stake when animation leaves behind the limited confines of the cinema screen to surface in the white cube or a museum wing? Purists may consider the new, warm embrace by the art world as a suffocating gesture. What is the compensation for – on average – a serious loss of projection quality and an intense, collective experience? From a historical point of view however, there are several good reasons to argue that animation does belong to the exhibition space, and that the development of animation as an artistic practice actually precedes the cinema with at least three centuries, starting already with the magic lantern. From its origins, animation can be understood both as a method (a technology) and as a metaphor (a strategy for provoking interpretation). From the earliest days of museology, via the modernist white cube and the ubiquity of electronic images in the digital era, there is the recurring ambition to turn the site of an exhibition into a 'space of wonder,' an actualization of the historic Wunderkammer (curiosity chamber), where the visitor is positioned in a dynamic constellation that plays with the parameters of time and space. Yet the practical manifestations of animation in the field of visual art often manifest a rather different, more derivative character. -

Marie's Last Line

MIKE HOOLBOOM Mourning Pictures Weightless pans lend the viewer the eyes of a body gripped by fever, as if these re-enactments were being watched over by ghosts. Nurses pad silently in white uniforms delivering milk and meals, while the patients wait, read, play checkers, stare out windows, never far from the crisp white linen of their beds. The mood throughout is haunting and elegiac; despite the utopian curatives of a new science, it is difficult to shake the feeling that the end of the world is not far. 279 The third act begins in darkness, with the voice of Marie, committed before adolescence to the sanitorium, recalling her experience from the far shore of the present. Family life appears in colour vignettes, posing for portraits, or gathered to eat before her brother sails off for war. Over her recollections the dominant formal trope is a virtuosic superimposition, moments of found footage erupting from prairie fields or the sanitorium; these places of waiting become a stage for reflection. Like the patients themselves, this is a landscape of ghosts longing for remembrance. For mourning. Marie's Last Line This moderate feeling has become familiar to me. It is now all I allow myself to experience, even in moments of great joy. After Brenda, Donigan Cumming Beyond the Absurd, Beyond Cruelty: Donigan Cumming’s Staged Realities Sally Berger Cruelty. Without an element of cruelty at the foundation of every spectacle, the theatre is not possible. In the state of degeneracy, in which we live, it is through the skin that metaphysics will be made to re-enter our minds. -

Women's Experimental Cinema

FILM STUDIES/WOMEN’S STUDIES BLAETZ, Women’s Experimental Cinema provides lively introductions to the work of fifteen avant- ROBIN BLAETZ, garde women filmmakers, some of whom worked as early as the 1950s and many of whom editor editor are still working today. In each essay in this collection, a leading film scholar considers a single filmmaker, supplying biographical information, analyzing various influences on her Experimental Cinema Women’s work, examining the development of her corpus, and interpreting a significant number of individual films. The essays rescue the work of critically neglected but influential women filmmakers for teaching, further study, and, hopefully, restoration and preservation. Just as importantly, they enrich the understanding of feminism in cinema and expand the ter- rain of film history, particularly the history of the American avant-garde. The essays highlight the diversity in these filmmakers’ forms and methods, covering topics such as how Marie Menken used film as a way to rethink the transition from ab- stract expressionism to Pop Art in the 1950s and 1960s, how Barbara Rubin both objecti- fied the body and investigated the filmic apparatus that enabled that objectification in her film Christmas on Earth (1963), and how Cheryl Dunye uses film to explore her own identity as a black lesbian artist. At the same time, the essays reveal commonalities, in- cluding a tendency toward documentary rather than fiction and a commitment to nonhi- erarchical, collaborative production practices. The volume’s final essay focuses explicitly on teaching women’s experimental films, addressing logistical concerns (how to acquire the films and secure proper viewing spaces) and extending the range of the book by sug- gesting alternative films for classroom use. -

Diagrams of Motion’ Wilson, Ewan

University of Dundee ‘Diagrams of Motion’ Wilson, Ewan Published in: Animation DOI: 10.1177/1746847718782890 Publication date: 2018 Document Version Peer reviewed version Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Wilson, E. (2018). ‘Diagrams of Motion’: Stop-Motion Animation as a Form of Kinetic Sculpture in the Short Films of Jan Švankmajer and the Brothers Quay. Animation, 13(2), 148-161. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746847718782890 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 02. Oct. 2021 Author contact details: Ewan Wilson, University of Dundee, Nethergate, DD1 4HN E-mail: [email protected] Author Biography: Ewan is a final-year SGSAH PhD candidate in Film Studies at the University of Dundee, specialising in British and European cinema. He previously completed an MA(hons) in English and Film Studies and an MLitt in Film Studies, supported by a Carnegie Cameron scholarship, also at the University of Dundee. -

Journal of Film Preservation

Journal of Film Preservation Journal of Film Preservation Contributors to this issue... Ont collaboré à ce numéro... Journal Han participado en este número... 73 04/2007 MAGDALENA ACOSTA of Film Miembro del Comité ejecutivo de FIAF (México) ANTTI ALANEN Head of the FIAF Programming and Access to Preservation Collections Commission, Programmer at the Finnish Film Archive (Helsinki) HOU HSIAO-HSIEN MICHELLE AUBERT Film Director (Taipei) Conservatrice, Directrice adjointe, Archives françaises du film - CNC (Bois d’Arcy) CLYDE JEAVONS Programmer at the National Film Theatre of the ROBERT DAUDELIN BFI (London) Rédacteur en chef du Journal of Film Preservation (Montréal) ÉRIC LE ROY Chef du Service accès, valorisation et MARCO DE BLOIS enrichissement des collections la de Revista Internacional Federación Fílmicos Archivos de Conservateur cinéma d’animation à la Archives françaises du film - CNC (Bois d’Arcy) Cinémathèque québécoise (Montréal) RICHARD LOCHEAD CHRISTIAN DIMITRIU Manager, Film and Broadcast, Library and Editorial Board Member of the Journal of Film Archives Canada (Ottawa) Preservation (Brussels) FEREIDOUN MAHBOUBI GIAN LUCA FARINELLI Chargé d’études documentaires aux Archives Directeur de la Cineteca del Commune di françaises du film – CNC (Bois d’Arcy) the by Published Federation International Archives Film of Bologna (Bologna) DAVIDE POZZI JON GARTENBERG Head of Film Restoration and Conservation at President of Gartenberg Media Enterprises, Inc. L’Immagine Ritrovata (Bologna) (New York) YOLANDE RACINE Hou Hsiao-Hsien THORARINN -

I. CREATIVITY in SOCIOCULTURAL CONTEXTS Philosophy of Matter

CREATIVITY STUDIES ISSN 2345-0479 / eISSN 2345-0487 2015 Volume 8(1): 3–11 doi:10.3846/23450479.2015.1015464 I. CREATIVITY IN SOciOCULTURAL CONTEXTS PHILOSOPHY OF MATTER MANIPULATION IN BROTHERS QUAY’ METAPHORICAL ANIMATION WORLD Basia NIKIFOROva Lithuanian Culture Research Institute, Department of Contemporary Philosophy, Saltoniškių g. 58, 08105 Vilnius, Lithuania E-mails: [email protected]; [email protected] Received 30 October 2014; accepted 02 February 2015 The paper deals with the concept of matter manipulation and its vitality in the Brothers Quay’ works. The matter manipulation is not limited to the ac- tual “matter”. Brothers Quay perceive the acting “matters” as symbols and signs of human activities and relationships. For them, there is no fundamental difference between “matters” and living beings inhabiting their films. Matter manipulation is the process of “machine” production, reproduction, destruc- tion, repair and deconstruction. The creation process acts as a magic spell, in which objects are transformed into something else. The Street of Crocodiles (1986) is an example of deep understanding of lifelessness as a mask, a kind of conspiracy, behind which unknown life forms hide. Brothers Quay’ creat- ive works tell us about autonomous existence of objects beyond their direct utilitarian purpose. The article will be devoted to such problems as syner- gistic vision of the world in which the material and the spiritual are insep- arable. Despite the paradox of visual embodiment, it fits into a philosophical metatheory of the “new materialism”, which transversely crosses streams of matter and mind, body and soul, nature and culture. The legacy of Brothers Quay open to us the world of ordinary, “banal” things, signs of time on their body shell, in contradiction with the dominance of endless consumption of new, intrusive advertising and cult of youth, in which there is no room for “sign of the times”.