Working Paper 1 – Disputed Land Rights and Conservation-Led Displacement

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kanchanpur District

District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) For Kanchanpur District ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Government of Nepal District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) of Kanchanpur District Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Department of Local Infrastructure Development and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR) District Development Committee, Kanchanpur Volume I Final Report January. 2016 Prepared by: Project Research and Engineering Associates for the District Development Committee (DDC) and District Technical Office (DTO), with Technical Assistance from the Department of Local Infrastructure and Agricultural Roads (DOLIDAR), Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development and grant supported by DFID through Rural Access Programme (RAP3). District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) For Kanchanpur District ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Project Research and Engineering Associates 1 District Transport Master Plan (DTMP) For Kanchanpur District ------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Project Research and Engineering Associates Lagankhel, Lalitpur Phone: 5539607 Email: [email protected] -

Nepal • FWR/MWR Floods and Landslides Situation Report # 1 8 October 2009

Nepal • FWR/MWR Floods and Landslides Situation Report # 1 8 October 2009 This report was issued by UN OCHA Nepal. It covers the period from October 4 - 8 2009. HIGHLIGHTS • Ten districts in the Mid and Far Western Regions have been affected by the floods and landslides caused by four days of continuous rain; • More than 40 deaths have been recorded, but the impact of landslides has been most felt in Accham (20 deaths) and Dadeldhura (12 deaths) districts, and that of the floods in Kailali and Kanchanpur districts (source: NRCS); • More than 3,000 families and 18,000 individuals have been affected, and at least 1,000 families have been displaced (source: NRCS); • Regional and district level resources can meet current emergency needs and the District Disaster Relief Committees are coordinating efforts in all affected districts; • Damage to roads and telecommunication systems have obstructed search and rescue efforts, especially in hilly and mountainous districts and remote VDCs in Terai districts. • Over the past 24 hours rains have decreased and water levels in many rivers receded. I. Situation Overview At least ten districts in the far- and mid-western regions have been affected by the heavy rains which started in the far-western districts and moved eastward. More than 40 deaths have been reported up to now, including 12 in Dadeldhura district, and 20 in Accham district (source: NRCS). The amount of rainfall was especially high in Doti and Dadeldhura districts, where it reached 245.7 mm and 227.4 mm respectively in a 24-hour period (Meteorological Forecasting Division website). -

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal

Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal Volumes: Volume I : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 1 Volume II : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 2 Volume III : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 3 Volume IV : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 4 Volume V : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 5 Volume VI : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 6 Volume VII : Forest & Watershed Profile of Province 7 Government of Nepal Ministry of Forests and Soil Conservation Department of Forest Research and Survey Kathmandu July 2017 © Department of Forest Research and Survey, 2017 Any reproduction of this publication in full or in part should mention the title and credit DFRS. Citation: DFRS, 2017. Forests and Watershed Profile of Local Level (744) Structure of Nepal. Department of Forest Research and Survey (DFRS). Kathmandu, Nepal Prepared by: Coordinator : Dr. Deepak Kumar Kharal, DG, DFRS Member : Dr. Prem Poudel, Under-secretary, DSCWM Member : Rabindra Maharjan, Under-secretary, DoF Member : Shiva Khanal, Under-secretary, DFRS Member : Raj Kumar Rimal, AFO, DoF Member Secretary : Amul Kumar Acharya, ARO, DFRS Published by: Department of Forest Research and Survey P. O. Box 3339, Babarmahal Kathmandu, Nepal Tel: 977-1-4233510 Fax: 977-1-4220159 Email: [email protected] Web: www.dfrs.gov.np Cover map: Front cover: Map of Forest Cover of Nepal FOREWORD Forest of Nepal has been a long standing key natural resource supporting nation's economy in many ways. Forests resources have significant contribution to ecosystem balance and livelihood of large portion of population in Nepal. Sustainable management of forest resources is essential to support overall development goals. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

The Rufford Foundation Final Report

The Rufford Foundation Final Report Congratulations on the completion of your project that was supported by The Rufford Foundation. We ask all grant recipients to complete a Final Report Form that helps us to gauge the success of our grant giving. The Final Report must be sent in word format and not PDF format or any other format. We understand that projects often do not follow the predicted course but knowledge of your experiences is valuable to us and others who may be undertaking similar work. Please be as honest as you can in answering the questions – remember that negative experiences are just as valuable as positive ones if they help others to learn from them. Please complete the form in English and be as clear and concise as you can. Please note that the information may be edited for clarity. We will ask for further information if required. If you have any other materials produced by the project, particularly a few relevant photographs, please send these to us separately. Please submit your final report to [email protected]. Thank you for your help. Josh Cole, Grants Director Grant Recipient Details Your name Kalpana Bisht Understanding Ecology and Enhancing Conservation Status of Blue Project title bull in Nepal: A Case study of Suklaphanta Wildlife Reserve. RSG reference 14221-1 Reporting period March 2014-April 2015 Amount of grant £5933 Your email address [email protected] Date of this report 22nd May 2015 1. Please indicate the level of achievement of the project’s original objectives and include any relevant comments on factors affecting this. -

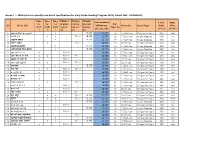

Annex 1 : - Srms Print Run Quantity and Detail Specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts)

Annex 1 : - SRMs print run quantity and detail specifications for Early Grade Reading Program 2019 ( Cohort 1&2 : 16 Districts) Number Number Number Titles Titles Titles Total numbers Cover Inner for for for of print of print of print # of SN Book Title of Print run Book Size Inner Paper Print Print grade grade grade run for run for run for Inner Pg (G1, G2 , G3) (Color) (Color) 1 2 3 G1 G2 G3 1 अनारकल�को अꅍतरकथा x - - 15,775 15,775 24 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 2 अनौठो फल x x - 16,000 15,775 31,775 28 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 3 अमु쥍य उपहार x - - 15,775 15,775 40 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 4 अत� र बु饍�ध x - 16,000 - 16,000 36 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 5 अ쥍छ�को औषधी x - - 15,775 15,775 36 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 6 असी �दनमा �व�व भ्रमण x - - 15,775 15,775 32 17.5x24 cms 80 gms Maplitho 4X0 1x1 7 आउ गन� १ २ ३ x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 8 आज मैले के के जान� x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 9 आ굍नो घर राम्रो घर x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 10 आमा खुसी हुनुभयो x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 20 21x27 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 11 उप配यका x - - 15,775 15,775 20 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4X4 12 ऋतु गीत x x 16,000 16,000 - 32,000 16 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 13 क का �क क� x 16,000 - - 16,000 16 14.8x21 cms 130 gms Art Paper 4X0 4x4 14 क दे�ख � स륍म x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 15 कता�तर छौ ? x 16,000 - - 16,000 20 17.5x24 cms 130 gms Art Paper 2X0 2x2 -

Disputed Land Rights and Conservation-Led Displacement: a Double Whammy on the Poor

[Downloaded free from http://www.conservationandsociety.org on Tuesday, July 29, 2014, IP: 129.79.203.179] || Click here to download free Android application for this journal Conservation and Society 12(1): 65-76, 2014 Article Disputed Land Rights and Conservation-led Displacement: A Double Whammy on the Poor Lai Ming Lama,# and Saumik Paulb aOsaka University, School of Human Sciences, Suita City, Osaka, Japan bUniversity of Nottingham (Malaysia Campus), School of Economics, Selangor Darul Ehsan, Malaysia #Corresponding author. E‑mail: [email protected] Abstract The practice of conservation through displacement has become commonplace in developing countries. However, resettlement programs remain at very low standards as government policies only focus on economic-based compensation which often excludes socially and economically marginalised groups. In this paper, based on a case study of the displaced indigenous people, the Rana Tharus, from the Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserve in Nepal, we argue that compensation as a panacea is a myth as it does not effectively replace the loss of livelihoods. This is particularly the case when the indigenous community’s customary rights to land are not legally protected. Our ethnographic data support the contention that the history of social exclusion is rooted in the land reform and settlement policies, which deprived the Rana Tharus of proper land rights. The present land compensation scheme resulted in a ‘double whammy’ on indigenous forest dwellers. The legal land title holders on average received less than 60% of their land. Moreover, due to the poor quality of soil in the resettlement areas the average crop yield was less than half the quantity produced before displacement. -

Strengthening the Role of Civil Society and Women in Democracy And

HARIYO BAN PROGRAM Monitoring and Evaluation Plan 25 November 2011 – 25 August 2016 (Cooperative Agreement No: AID-367-A-11-00003) Submitted to: UNITED STATES AGENCY FOR INTERNATIONAL DEVELOPMENT NEPAL MISSION Maharajgunj, Kathmandu, Nepal Submitted by: WWF in partnership with CARE, FECOFUN and NTNC P.O. Box 7660, Baluwatar, Kathmandu, Nepal First approved on April 18, 2013 Updated and approved on January 5, 2015 Updated and approved on July 31, 2015 Updated and approved on August 31, 2015 Updated and approved on January 19, 2016 January 19, 2016 Ms. Judy Oglethorpe Chief of Party, Hariyo Ban Program WWF Nepal Baluwatar, Kathmandu Subject: Approval for revised M&E Plan for the Hariyo Ban Program Reference: Cooperative Agreement # 367-A-11-00003 Dear Judy, This letter is in response to the updated Monitoring and Evaluation Plan (M&E Plan) for the Hariyo Program that you submitted to me on January 14, 2016. I would like to thank WWF and all consortium partners (CARE, NTNC, and FECOFUN) for submitting the updated M&E Plan. The revised M&E Plan is consistent with the approved Annual Work Plan and the Program Description of the Cooperative Agreement (CA). This updated M&E has added/revised/updated targets to systematically align additional earthquake recovery funding added into the award through 8th modification of Hariyo Ban award to WWF to address very unexpected and burning issues, primarily in four Hariyo Ban program districts (Gorkha, Dhading, Rasuwa and Nuwakot) and partly in other districts, due to recent earthquake and associated climatic/environmental challenges. This updated M&E Plan, including its added/revised/updated indicators and targets, will have very good programmatic meaning for the program’s overall performance monitoring process in the future. -

Annual Report 2017

ANNUAL REPORT 2017 National Trust for Nature Conservation MISSION STATEMENT “To conserve, manage and promote nature in all its diversity balancing human needs with the environment on a sustainable basis for posterity-ensuring maximum community participation with due cognizance of the linkages between economics, environment and ethics through a process in which people are both the principal actors and beneficiaries.” With over 3 decades of experience in the field of participatory conservation, right from the grassroots level to policy and core research, the National Trust for Nature Conservation (NTNC) continues to steer a phenomenal track record of driving the principal of Conservation for Development. NTNC, established in 1982 by a legislative act, is an autonomous and not-for-profit organization, mandated to work in the field of nature conservation in Nepal. From its very inception the Trust fully understands that local communities matter, and that they are eventually stipulated to become the flag bearers of all conservation initiatives. To ensure that the locus of sustainable conservation is bearing on each of these communities, the Trust has successfully implemented various projects from nature and biodiversity conservation, cultural heritage protection, ecotourism development, alternative energy promotion, gender empowerment, livelihood enhancement. Given its deep integration with the community, and coupled with its expertise, the Trust maintains an unmatched advantage—whether it be in matters related to wildlife research and monitoring, community engagement, anti-poaching, conservation education, needs identification, assessment and impact study, capacity building, or in matters related to good governance and local institutional empowerment. This is one of the main reasons why NTNC continues to embrace a reputation that is crucial in cohabiting the development agendas for a large number of multilateral stakeholder projects. -

Technical Assistance Consultant's Report Nepal: Far Western Region

Technical Assistance Consultant’s Report Project Number: TA 8817 January 2017 Nepal: Far Western Region Urban Development Project (Volume 2) Prepared by: Michael Green London, United Kingdom For: Ministry of Urban Development Department of Urban Development and Building Construction This consultant’s report does not necessarily reflect the views of ADB or the Government concerned, and ADB and the Government cannot be held liable for its contents. (For project preparatory technical assistance: All the views expressed herein may not be incorporated into the proposed project’s design. Government of Nepal Ministry of Urban Development Second Integrated Urban Development Project (IUDP2) (PPTA 8817–NEP) Draft Final Report Discussion Note # 1 Economic and Urban Development Vision for Far Western Terai Region August 2015 Discussion Note # 1 Economic and Urban Development Vision for Far Western Terai Region Part A : Economic Development Vision and Strategy TA 8817-NEP: Second Integrated Urban Development Project Discussion Note # 1 Economic and Urban Development Vision for Far Western Terai Region Part A : Economic Development Vision and Strategy Contents 1 Context 1 1.1 Purpose of the Vision 1 1.2 Nepal – A gifted country 1 1.3 The Terai – the bread basket of Nepal 2 1.4 Far West Nepal – Sundar Sudur Paschim 3 2 Prerequisites for Transformational Growth and Development 4 2.1 The Constitution and decentralization of governance 4 2.2 Strengthening Nepal’s economic links with India 4 2.3 Developing Transportation 5 2.3.1 Developing strong transport -

Final Report

Darwin Initiative: Final Report Darwin Project Information Project reference 22-009 Project title Securing Shuklaphanta Wildlife Reserve’s Grassland and wellbeing of local communities Host country(ies) Nepal Contract holder institution Zoological Society of London Partner institution(s) Department of National Parks and Wildlife Conservation (DNPWC), National Trust for Nature Conservation (NTNC), Himalayan Nature (HN) Darwin grant value £ 284,417 Start/end dates of project 1 April 2015 to 31 March 2018 Project leader’s name Hem Sagar Baral Project website/blog/Twitter https://www.zsl.org/conservation/regions/asia/Shuklaphanta- wildlife-reserve-%E2%80%93-nepal https://himalayannature.org/index.php/2017/01/17/darwin- initiative-securing-shuklaphanta-wildlife-reserves-grasslands- and-wellbeing-of-local-communities/ Report author(s) and date ZSL: Hem Sagar Baral, Gitanjali Bhattacharya, Bhagawan Raj Dahal, Tek Raj Bhatt, Jake Williams, Pradeep Raj Joshi DNPWC: Bed Kumar Dhakal, Gopal Bahadur Ghimire, NTNC: Dr Naresh Subedi, Anil Prasai Himalayan Nature: Chandra Jung Hamal 30 June 2018 Project Rationale The project was designed in consultation with Shuklaphanta National Park (ShNP) and the Buffer Zone Management Committee (BZMC), a representative committee of communities living around the park, to address the problem of unregulated and illegal grazing inside the park. ShNP Management Plan identified overgrazing in core and peripheral areas as a major cause of the decline of grassland habitat and wildlife. Nearly 17,000 cattle each day, constituting 75% of those owned by buffer zone communities, used to graze freely within the core and peripheral area of the park. The frequent and unregulated sharing of grazing land not only resulted in overgrazing, but also had increased the risk of disease transmission between domestic ruminants and wild animals. -

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background Forest is not only the largest natural resource in terms of spatial coverage but also an important means for their products such as fuelwood, fodder, timber and medicines to majority of the people. The conservation of forest resources may also help in diversification of wild life and biodiversity. The fuelwood from the forest products is a major source of energy for majority of the rural people. Fuelwood is primarily used for cooking and heating. The forests are the only sources that have received heavy pressure as a result of meeting ever increasing demand of fuelwood. Forests, which are main resource of biomass energy, have already been exploited beyond their sustainable capacity and are becoming relatively scarce (Katuwal and Bohara 2009). As more than 80 % of the energy needs in rural area are met by fuelwood, thus exerting immense pressure on the forest resources of the country with negative impacts on biodiversity conservation (WECS 2006). The biomass consumption has vast implications both for deterioration of natural resources which has been home to large number of wild flora and fauna. Alternatives to wood and biomass based energy is unrealistic to the large majority of households in the near future as well. In this scenario, efforts and initiatives geared towards a sustainable alternative energy program seems crucial as a mitigating measure for the harmful effects derived from the excessive use of natural resources for energy (Thapa and KC 2009). Promotion of alternative energy has been a major component of biodiversity conservation, as it reduces human pressure in the park and buffer zone forests.