Gallery Guide Picasso. Figures

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

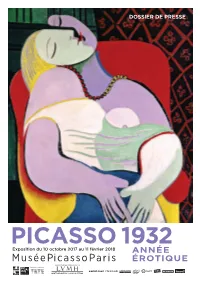

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

Une Saison Picasso

UNE SAISON PICASSO ROUEN 1er AVRIL – 11 SEPTEMBRE 2017 DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE RÉALISÉ PAR LE SERVICE DES PUBLICS ET LE SERVICE ÉDUCATIF DE LA RÉUNION DES MUSÉES MÉTROPOLITAINS musees-rouen-normandie.fr UNE SAISON PICASSO DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE SOMMAIRE Dossier pédagogique réalisé par le service des publics et le service éducatif de la réunion des Musées Métropolitains 03 ÉDITO 04 BOISGELOUP, L’ATELIER NORMAND DE PICASSO — MUSÉE DES BEAUX-ARTS 09 FICHE ŒUVRE : PABLO PICASSO, Minotaure et cheval, 15 avril 1935 11 FICHE ŒUVRE : PABLO PICASSO, Figure assise dans un fauteuil rouge, fin janvier 1932 14 PICASSO SCULPTURES CÉRAMIQUES — MUSÉE DE LA CÉRAMIQUE 15 FICHE ŒUVRE : PABLO PICASSO, Colombe, 1953 18 GONZÁLEZ – PICASSO : UNE AMITIÉ DE FER — MUSÉE LE SECQ DES TOURNELLES 19 FICHE ŒUVRE : JULIO GONZÁLEZ, Femme à la corbeille, 1934 22 BIOGRAPHIES PICASSO – GONZÁLEZ 25 BIBLIOGRAPHIE 26 INFORMATIONS PRATIQUES 2 RÉUNION DES MUSÉES MÉTROPOLITAINS PICASSO, CE NORMAND… Peu de gens le savent, Picasso a résidé et travaillé pendant cinq années en Normandie, dans son château de Boisgeloup, près de Gisors. Jusqu’ici, aucun ouvrage, aucune exposition n’avaient été consacrés à cette période intensément créative, qui s’étend de 1930 à 1935, et voit Picasso pratiquer particulièrement la sculpture, mais aussi la peinture, le dessin, la gravure, la photographie avant de s’adonner à l’écriture. La Normandie, par ailleurs, n’avait encore jamais accueilli une exposition significative dédiée au grand maître du XXe siècle. Pour réparer ces lacunes, nous avons imaginé une véritable Saison Picasso, et réuni les meilleurs partenaires pour déployer pas moins de trois expositions dans autant de musées différents. -

Picasso, L'éternel Féminin

Exposition temporaire Dossier pour les enseignants Service éducatif Musée des beaux-arts de Quimper Picasso, l’éternel féminin Sommaire Introduction p.3 1/ Ecce homo - Picasso, quelques repères chronologiques p.5 - Picasso, quelques repères formels p.9 2/ L’exposition - Picasso et le portrait p.11 - Les thèmes de l’exposition p.15 - Des femmes longuement portraiturées p.21 3/ La gravure - Picasso et la gravure p.27 - La production (schéma de synthèse) p.31 - Coups de projecteur La Suite Vollard - Les 357 - Les 156 p.33 - Glossaire de la gravure selon Picasso p.41 4/ Bibliographie p.47 5/ Propositions pédagogiques p.49 6/ Informations pratiques p.55 2 Picasso, l’éternel féminin Introduction Bâtie à partir des riches collections graphiques de la Fondation Picasso (Museo Casa Natal), Ville de Malaga, l’exposition présentée à Quimper puis à Pau décline l’importance du modèle féminin dans l’œuvre de Pablo Picasso. Au travers d’une sélection de près de 70 estampes, réalisées entre les années 1930 et 1970, et de plusieurs œuvres prêtées par des musées français, le public est invité à découvrir les multiples variations que l’artiste a créées autour de la femme. L’ensemble des gravures exposées, une première en France, permet de voir combien les femmes de la vie de Picasso mais aussi les femmes imaginées, rêvées et fantasmées, ont compté dans sa production artistique. Fernande, Marie-Thérèse, Dora, Françoise et Jacqueline ont marqué son œuvre qui brouille les frontières entre l’art et la vie. La gravure occupe une place privilégiée dans la pensée picturale de Picasso. -

Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris

MEDIA RELEASE ‘If the progress of 20th-century art was to be defined by the achievements of a single individual, that individual would indisputably be Picasso.’ Edmund Capon PICASSO Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris SYDNEY ONLY 12 November 2011 – 25 March 2012 ART GALLERY NSW ART GALLERY NSW 1922 1904 ‘I paint the way some people write their autobiography. The paintings, finished or not, are the pages from my diary…’ Pablo Picasso 1932 clockwise from top left: La Célestine (La Femme à la taie) (La Celestina (The woman with a cataract) 1904 Deux femmes courant sur la plage (La course) (Two women running on the beach (The race) 1922 Femmes à la toilette (Women at their toilette) 1956 La lecture (The reader) 1932 1956 ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES / 5 ART GALLERY NSW 1906 1937 1950 clockwise from top left: Portrait de Dora Maar (Portrait of Dora Maar) 1937 Autoportrait (Self-portrait) 1906 La chèvre (The goat) 1950 Le baiser (The kiss) 1969 1969 ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES / 2 PICASSO Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris Picasso in front of Portrait de femme by Henri Rousseau 1932, photo by Brassaï ‘This is the great Picasso show to which ‘This exceptional exhibition covering we have often aspired but not yet achieved every aspect of Picasso’s multifaceted in Australia. Make the most of it because output and all the artistic media in which we will never have such a show again. he exercised his extraordinary creativity, Seven decades of Picasso’s relentless work, constitutes the foundation stone for a capturing every phase of his extraordinary groundbreaking partnership between the career, including masterpieces from his Blue, Musée National Picasso and the Art Gallery Rose, Expressionist, Cubist, Neoclassical and of New South Wales.’ Surrealist periods. -

Anguage Instruction; *Sociocultural Patterns; Spanish; *Spanish Literature

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 386 937 FL 023 249 AUTHOR Hines, Marion E., Ed. TITLE The Child in Francophone and Hispanic Literature: Teaching Culture through Literature. INSTITUTION District of Columbia Public Schools, Washington, D.C.; Georgetown Univ., Washington, DC. Foreign Language Teachers Inst. PUB DATE 92 NOTE 200p. AVAILABLE FROMGeorgetown University Press, Washington, DC. PUB TYPE Collected Works General (020) Guides Non-Classroom Use (055) LANGUAGE English; French; Spanish EDRS PRICE MF01/PC08 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Children; *Childrens Literature; Cultural Awareness; *Cultural Education; Foreign Countries; French; *French Literature; Secondary Education; Second anguage Instruction; *Sociocultural Patterns; Spanish; *Spanish Literature ABSTRACT This guide, intended for secondary school teachers of French and Spanish, integrates the teaching of culture and literature with a focus on the child in the target culture. The readings and discussion notes are designed to focus student attention on the target culture through these topics. An introductory section discusses the teaching of culture through literature. The second section provides reading outlines for independent study on specific segments of Francopnone and Spanish literature (e.g., African and Antillean, Mexican, etc.). The third section contains a series of short papers on children in literature, and the fourth consists of instructional plans for individual literary works. The fifth and final section lists supplementary instructional aids and materials for each language. An extensive list of references is contained in this section. Contents are in English,.French, and Spanish. (MSE) *********************************************************************** * Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best ti.at can be made * * from the original document. * *********************************************************************** THE CHILD IN FRANCOPHONE AND HISPANIC LITERATURE .Teaching Culture Through Literature EDITED BY Marion E. -

Picasso - Enseignant Primaire.Pdf

DOSSIER PEDAGOGIQUE ECOLE ÉLÉMENTAIRE Dossier pédagogique. Enseignant Primaire 1 Carrières de Lumières SOMMAIRE I – PRÉPARATION DE LA VISITE 1. Présentation du site 3 2. Les Carrières, l’exposition immersive et les programmes scolaires 4 3. Les objectifs d’apprentissage 5 4. Méthode du dossier : de la préparation au réinvestissement en classe 7 5. La chronologie de la vie et de l’œuvre de Pablo Picasso 8 6. Histoire des arts : la peinture espagnole de Goya, Picasso, Rusinol, Zuloaga, Sorolla 9 7. Plan repère des Carrières 10 8. Informations et réservation 11 II – PENDANT LA VISITE POUR LES CLASSES DU CYCLE 2 Parcours de l’exposition immersive 12 III – APRÈS LA VISITE 1. Découverte des tableaux des maîtres espagnols et de Picasso 14 2. Fiche de correction des questionnaires 21 Qu’as-tu retenu? Quiz bilan 23 II – PENDANT LA VISITE POUR LES CLASSES DU CYCLE 3 Parcours de l’exposition immersive 25 III – APRÈS LA VISITE 1. Découverte des tableaux des maîtres espagnols et de Picasso 27 2. Initiation à l’Histoire des arts 38 3. Fiche de correction des questionnaires 40 Qu’as-tu retenu? Quiz bilan 46 2 AVANT LA VISITE 1 – Présentation du site Au pied de la cité des Baux-de-Provence, au cœur des Alpilles, se trouve un lieu chargé de mystère : le Val d’Enfer. Ce vallon aux concrétions minérales exceptionnelles a inspiré les artistes depuis toujours : Dante y planta le décor de La Divine Comédie alors que Gounod y créa son opéra Mireille. Plus tard, Cocteau est venu réaliser, au sein même des carrières, Le Testament d’Orphée. -

Decorative Painting and Politics in France, 1890-1914

Decorative Painting and Politics in France, 1890-1914 by Katherine D. Brion A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History of Art) in the University of Michigan 2014 Doctoral Committee: Professor Howard Lay, Chair Professor Joshua Cole Professor Michèle Hannoosh Professor Susan Siegfried © Katherine D. Brion 2014 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I will begin by thanking Howard Lay, who was instrumental in shaping the direction and final form of this dissertation. His unbroken calm and good-humor, even in the face of my tendency to take up new ideas and projects before finishing with the old, was of huge benefit to me, especially in the final stages—as were his careful and generous (re)readings of the text. Susan Siegfried and Michèle Hannoosh were also early mentors, first offering inspiring coursework and then, as committee members, advice and comments at key stages. Their feedback was such that I always wished I had solicited more, along with Michèle’s tea. Josh Cole’s seminar gave me a window not only into nineteenth-century France but also into the practice of history, and his kind yet rigorous comments on the dissertation are a model I hope to emulate. Betsy Sears has also been an important source of advice and encouragement. The research and writing of this dissertation was funded by fellowships and grants from the Georges Lurcy Foundation, the Rackham Graduate School at the University of Michigan, the Mellon Foundation, and the Getty Research Institute, as well as a Susan Lipschutz Award. My research was also made possible by the staffs at the Bibliothèque nationale de France, the Institut nationale d’Histoire de l’Art, the Getty Research Library, the Musée des arts décoratifs/Musée de la Publicité, and the Musée Maurice Denis, ii among other institutions. -

Pablo Picasso Et Gertrude Stein, Une Rencontre De Migrants À Paris Au Début Du Xxe Siècle

Pablo Picasso et Gertrude Stein, une rencontre de migrants à Paris au début du XXe siècle Annie Cohen-Solal • colloque Revoir Picasso • 28 mars 2015 Je travaille sur le monde de l’art dans une perspective d’his- L’interaction entre Gertrude Stein et Pablo Picasso est passion- toire sociale et j’y étudie les liens entre l’artiste – acteur nante, car elle montre la multiplicité des liens qui peuvent se manifeste de ce réseau – et ceux que l’on appelle les acteurs tisser entre acteurs du monde de l’art. Les Stein sont d’abord dynamiques – c’est-à-dire les galeristes, directeurs de musée, des collectionneurs et, avant de parler de Gertrude, il faut critiques et collectionneurs – qui, autour de lui, mettent en mentionner son frère Leo, l’un des très grands collectionneurs place ses conditions de production. Parmi les acteurs dyna- des États-Unis à cette époque, un homme qu’Alfred Barr (qui miques qui accompagnent Picasso, on pourrait citer de dirigera le Museum of Modern Art à partir de 1929) décrira nombreux écrivains, tels que Max Jacob ou André Breton, comme « le plus grand érudit de son temps3 ». C’était un col- rappeler l’historique de l’acquisition par Jacques Doucet lectionneur acharné, qui avait déjà fait le tour du monde et des Demoiselles d’Avignon, penser à l’amitié très forte qui liait qui se rendait compte que l’on pouvait « être à Montparnasse le peintre à Guillaume Apollinaire, ou encore rendre compte sans savoir ce qui se passe à Montmartre4 ». Face aux Stein, de la pièce Le Désir attrapé par la queue, écrite par l’artiste en nous sommes dans une configuration sociale très particulière, janvier 1941 – et dont la première lecture, animée par Albert puisqu’il s’agit d’une famille de grands bourgeois américains Camus avec, parmi les seconds rôles, Raymond Queneau, – similaire, en cela, à la famille d’Alfred Stieglitz –, qui a émi- Michel Leiris ou Jean-Paul Sartre, eut lieu le 19 mars 1944 gré d’Allemagne vers les États-Unis dans les années 1860, et dans le salon de Michel Leiris1. -

DP Picasso1932 Web FR.Pdf

2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE Du 10 octobre 2017 au 11 février 2018 au Musée national Picasso-Paris, grâce au soutien de LVMH/Moët Hennessy - Louis Vuitton Picasso 1932. Année érotique est la première exposition dédiée à une année de création entière chez Picasso, allant du 1er janvier au 31 décembre dune même année. Lexposition présentera des chefs-duvre essentiels dans la carrière de Picasso comme Le Rêve (huile sur toile, collection particulière) et de nombreux documents darchives replaçant les créations de cette année dans leur contexte. Cet événement, organisé en partenariat avec la Tate Modern de Londres, fait le pari dinviter le visiteur à suivre au quotidien, dans un parcours rigoureusement chronologique, la production dune année particulièrement riche. Il questionnera la célèbre formule de lartiste selon laquelle « luvre que lon fait est une façon de tenir son journal », qui sous-entend lidée dune coïncidence entre vie et création. Parmi les jalons de cette année exceptionnelle se trouvent les séries des baigneuses et les portraits et compositions colorées autour de la figure de Marie-Thérèse Walter, posant la question du rapport au surréalisme. En parallèle de ces uvres sensuelles et érotiques, lartiste revient au thème de la Crucifixion, tandis que Brassaï réalise en décembre un reportage photographique dans son atelier de Boisgeloup. 1932 voit également la « muséification » de luvre de Picasso à travers lorganisation des rétrospectives à la galerie Georges Petit à Paris et au Kunsthaus de Zurich qui exposent, pour la première fois depuis 1911, le peintre espagnol au public et aux critiques. Lannée est enfin marquée par la parution du premier volume du Catalogue raisonné de luvre de Pablo Picasso, publié par Christian Zervos, qui place lauteur des Demoiselles dAvignon dans une exploration de son propre travail. -

OLGA PICASSO Exposition Du 21 Mars Au 3 Septembre 2017 2

DOSSIER DE PRESSE OLGA PICASSO Exposition du 21 mars au 3 septembre 2017 2 1. OLGA PICASSO p. 3 1. 1 LE PARCOURS DE LEXPOSITION p. 5 1.2 LE COMMISSARIAT p. 21 1.3 LE CATALOGUE DE LEXPOSITION p. 23 1.4 LA PROGRAMMATION CULTURELLE DE LEXPOSITION p. 40 1.5 LA MÉDIATION AUTOUR DE LEXPOSITION p. 41 1.6 ÉGALEMENT AUTOUR DE LEXPOSITION p. 45 2. LE MUSÉE NATIONAL PICASSO-PARIS p. 47 2.1 LES EXPOSITIONS PRÉSENTÉES PROCHAINEMENT AU MUSÉE p. 47 2.2 DES ÉVÉNEMENTS DEXCEPTION HORS LES MURS p. 48 2.3 LA PLUS IMPORTANTE COLLECTION AU MONDE DUVRES DE PICASSO p. 50 2.4 LHÔTEL SALÉ : UN ÉCRIN UNIQUE p. 52 3. REPÈRES p. 54 3.1 CHRONOLOGIES p. 54 3.2 DATES ET CHIFFRES CLÉS p. 58 4. LES PARTENAIRES DE LEXPOSITION p. 59 5. VISUELS DISPONIBLES POUR LA PRESSE p. 64 5.1 UVRES EXPOSÉES p. 64 5.2 VUES DU MUSÉE NATIONAL PICASSO-PARIS p. 68 6. INFORMATIONS PRATIQUES p. 69 7. CONTACTS PRESSE p. 70 1. OLGA PICASSO 3 Du 21 mars au 3 septembre 2017, le Musée national Picasso-Paris présente la première exposition consacrée aux années partagées entre Pablo Picasso et sa première épouse, Olga Khokhlova. À travers une vaste sélection de plus de 350 uvres, peintures, dessins, éléments de mobilier ainsi que de nombreuses archives écrites et photographiques inédites, cette exposition qui se déploie sur deux étages du musée, soit environ 800 m2, met en perspective la réalisation de quelques-unes des uvres majeures de Picasso en resituant cette production dans le cadre de cette histoire personnelle, filtre dune histoire politique et sociale élargie. -

La Création Artistique Entre Destin Et Liberté. Le Tableau Les Demoiselles D’Avignon (Partie II) Les Demoiselles D’Avignon Sont Sans Aucun Doute Un Coup De Maître

La création artistique entre destin et liberté. Le tableau Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (partie II) Les Demoiselles d’Avignon sont sans aucun doute un coup de maître. Sans se départir de la méditation, comme écrit André Salmon, mais aussi avec génie, minutie et humour, cette toile donne littéralement vie aux textes du Zohar. Et si tant Picasso que ses amis ont jeté sur ce tableau le voile du secret, c’est simplement qu’il représente ni plus ni moins que le Tetragrammaton : le Yod-Hé-Vau-Hé, le mot secret de la Kabbale. Marijo Ariens-Volker, Picasso et l’occultisme à Paris , 2016:382) 1. « Les Demoiselles d’Avignon » et les années précédentes. La période Rose. Le tableau Les Demoiselles d’Avignon a été précédé de la période la plus douce de la peinture de Picasso. Les critiques de l’art, d’une façon générale, expliquent cette période par le rencontre, en 1904, de Picasso avec Fernande Olivier. D’après le témoignage de celle-ci, ces temps ont été les années de la « bande à Picasso » dont le siège fut le « Bateau Lavoir », l’atelier que Picasso a loué avec d’autres artistes. Selon l’historien de l’art John Richardson, en plus que le rencontre avec Fernande Olivier, la période Rose (1904-1906) comprend aussi d’autres rencontres, comme celui de Picasso avec le poète André Salmon qui fut un des éléments constitutifs de la « bande à Picasso » : La proximité de l’imagerie entre ses poèmes et les peintures de la période Rose n’est guère surprenante puisque le poète et le peintre étaient devenus de si proches voisins. -

La Honte Et La Culpabilité

LA HONTE ET LA CULPABILITÉ: DESTINS DE FEMMES DANS LES RÉCITS ALGERIENS DU XX e ET XXI e SIÈCLE by FLORINA MATU METKA ZUPAN ČIČ, COMMITTEE CHAIR CARMEN MAYER-ROBIN BRUCE EDMUNDS JEAN LUC ROBIN ADRIENNE ANGELO A DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Modern Languages and Classics in the Graduate School of The University of Alabama TUSCALOOSA, ALABAMA 2012 Copyright Florina Matu 2012 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT This dissertation aims to explore a variety of representations of shame and guilt in twentieth and twenty-first century Algerian works written by women. More specifically, I argue that in three recent autofictional works by Assia Djebar ( Nulle part dans la maison de mon père ), Maïssa Bey ( Bleu blanc vert ) and Leïla Aslaoui ( Coupables ), by exposing feelings of shame and guilt, the authors accomplish a surprising task. Despite the negative connotation of these terms and the fact that those who bear them would normally choose to hide them carefully, shame and guilt, as experienced by the female characters in these works, open the door to feminine emancipation. In a patriarchal society in which revealing oneself and one’s feelings, especially as a woman, is a shameful act and a serious violation of modesty, the three authors invest their female characters with the authority to speak and to rebel against the norms of what should be an obedient Muslim woman. In addition to a thorough textual analysis developed in the three independent chapters dedicated to the three works of Djebar, Bey and Aslaoui, my dissertation displays a solid interdisciplinary component.