Anguage Instruction; *Sociocultural Patterns; Spanish; *Spanish Literature

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Impressionist & Modern

Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I 10 October 2019 Lot 8 Lot 2 Lot 26 (detail) Impressionist & Modern Art New Bond Street, London I Thursday 10 October 2019, 5pm BONHAMS ENQUIRIES PHYSICAL CONDITION IMPORTANT INFORMATION 101 New Bond Street London OF LOTS IN THIS AUCTION The United States Government London W1S 1SR India Phillips PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO has banned the import of ivory bonhams.com Global Head of Department REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE into the USA. Lots containing +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF ivory are indicated by the VIEWING [email protected] ANY LOT. INTENDING BIDDERS symbol Ф printed beside the Friday 4 October 10am – 5pm MUST SATISFY THEMSELVES AS lot number in this catalogue. Saturday 5 October 11am - 4pm Hannah Foster TO THE CONDITION OF ANY LOT Sunday 6 October 11am - 4pm Head of Department AS SPECIFIED IN CLAUSE 14 PRESS ENQUIRIES Monday 7 October 10am - 5pm +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 OF THE NOTICE TO BIDDERS [email protected] Tuesday 8 October 10am - 5pm [email protected] CONTAINED AT THE END OF THIS Wednesday 9 October 10am - 5pm CATALOGUE. CUSTOMER SERVICES Thursday 10 October 10am - 3pm Ruth Woodbridge Monday to Friday Specialist As a courtesy to intending bidders, 8.30am to 6pm SALE NUMBER +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 Bonhams will provide a written +44 (0) 20 7447 7447 25445 [email protected] Indication of the physical condition of +44 (0) 20 7447 7401 Fax lots in this sale if a request is received CATALOGUE Julia Ryff up to 24 hours before the auction Please see back of catalogue £22.00 Specialist starts. -

Impressionist & Modern

IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 IMPRESSIONIST & MODERN ART Thursday 1 March 2018 at 5pm New Bond Street, London VIEWING ENQUIRIES Brussels Rome Thursday 22 February, 9am to 5pm London Christine de Schaetzen Emma Dalla Libera Friday 23 February, 9am to 5pm India Phillips +32 2736 5076 +39 06 485 900 Saturday 24 February, 11am to 4pm Head of Department [email protected] [email protected] Sunday 25 February, 11am to 4pm +44 (0) 20 7468 8328 Monday 26 February, 9am to 5pm [email protected] Cologne Tokyo Tuesday 27 February, 9am to 3pm Katharina Schmid Ryo Wakabayashi Wednesday 28 February 9am to 5pm Hannah Foster +49 221 2779 9650 +81 3 5532 8636 Thursday 1 March, 9am to 2pm Department Director [email protected] [email protected] +44 (0) 20 7468 5814 SALE NUMBER [email protected] Geneva Zurich 24743 Victoria Rey-de-Rudder Andrea Bodmer Ruth Woodbridge +41 22 300 3160 +41 (0) 44 281 95 35 CATALOGUE Specialist [email protected] [email protected] £22.00 +44 (0) 20 7468 5816 [email protected] Livie Gallone Moeller PHYSICAL CONDITION OF LOTS ILLUSTRATIONS +41 22 300 3160 IN THIS AUCTION Front cover: Lot 16 Aimée Honig [email protected] Inside front covers: Lots 20, Junior Cataloguer PLEASE NOTE THAT THERE IS NO 21, 15, 70, 68, 9 +44 (0) 20 7468 8276 Hong Kong REFERENCE IN THIS CATALOGUE Back cover: Lot 33 [email protected] Dorothy Lin TO THE PHYSICAL CONDITION OF +1 323 436 5430 ANY LOT. -

Pablo Picasso, Published by Christian Zervos, Which Places the Painter of the Demoiselles Davignon in the Context of His Own Work

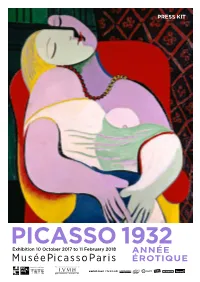

PRESS KIT PICASSO 1932 Exhibition 10 October 2017 to 11 February 2018 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE En partenariat avec Exposition réalisée grâce au soutien de 2 PICASSO 1932 ANNÉE ÉROTIQUE From 10 October to the 11 February 2018 at Musée national Picasso-Paris The first exhibition dedicated to the work of an artist from January 1 to December 31, the exhibition Picasso 1932 will present essential masterpieces in Picassos career as Le Rêve (oil on canvas, private collection) and numerous archival documents that place the creations of this year in their context. This event, organized in partnership with the Tate Modern in London, invites the visitor to follow the production of a particularly rich year in a rigorously chronological journey. It will question the famous formula of the artist, according to which the work that is done is a way of keeping his journal? which implies the idea of a coincidence between life and creation. Among the milestones of this exceptional year are the series of bathers and the colorful portraits and compositions around the figure of Marie-Thérèse Walter, posing the question of his works relationship to surrealism. In parallel with these sensual and erotic works, the artist returns to the theme of the Crucifixion while Brassaï realizes in December a photographic reportage in his workshop of Boisgeloup. 1932 also saw the museification of Picassos work through the organization of retrospectives at the Galerie Georges Petit in Paris and at the Kunsthaus in Zurich, which exhibited the Spanish painter to the public and critics for the first time since 1911. The year also marked the publication of the first volume of the Catalog raisonné of the work of Pablo Picasso, published by Christian Zervos, which places the painter of the Demoiselles dAvignon in the context of his own work. -

Une Saison Picasso

UNE SAISON PICASSO ROUEN 1er AVRIL – 11 SEPTEMBRE 2017 DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE RÉALISÉ PAR LE SERVICE DES PUBLICS ET LE SERVICE ÉDUCATIF DE LA RÉUNION DES MUSÉES MÉTROPOLITAINS musees-rouen-normandie.fr UNE SAISON PICASSO DOSSIER PÉDAGOGIQUE SOMMAIRE Dossier pédagogique réalisé par le service des publics et le service éducatif de la réunion des Musées Métropolitains 03 ÉDITO 04 BOISGELOUP, L’ATELIER NORMAND DE PICASSO — MUSÉE DES BEAUX-ARTS 09 FICHE ŒUVRE : PABLO PICASSO, Minotaure et cheval, 15 avril 1935 11 FICHE ŒUVRE : PABLO PICASSO, Figure assise dans un fauteuil rouge, fin janvier 1932 14 PICASSO SCULPTURES CÉRAMIQUES — MUSÉE DE LA CÉRAMIQUE 15 FICHE ŒUVRE : PABLO PICASSO, Colombe, 1953 18 GONZÁLEZ – PICASSO : UNE AMITIÉ DE FER — MUSÉE LE SECQ DES TOURNELLES 19 FICHE ŒUVRE : JULIO GONZÁLEZ, Femme à la corbeille, 1934 22 BIOGRAPHIES PICASSO – GONZÁLEZ 25 BIBLIOGRAPHIE 26 INFORMATIONS PRATIQUES 2 RÉUNION DES MUSÉES MÉTROPOLITAINS PICASSO, CE NORMAND… Peu de gens le savent, Picasso a résidé et travaillé pendant cinq années en Normandie, dans son château de Boisgeloup, près de Gisors. Jusqu’ici, aucun ouvrage, aucune exposition n’avaient été consacrés à cette période intensément créative, qui s’étend de 1930 à 1935, et voit Picasso pratiquer particulièrement la sculpture, mais aussi la peinture, le dessin, la gravure, la photographie avant de s’adonner à l’écriture. La Normandie, par ailleurs, n’avait encore jamais accueilli une exposition significative dédiée au grand maître du XXe siècle. Pour réparer ces lacunes, nous avons imaginé une véritable Saison Picasso, et réuni les meilleurs partenaires pour déployer pas moins de trois expositions dans autant de musées différents. -

Archives Départementales De La Marne 2020 Commune Actuelle

Archives départementales de la Marne 2020 Commune actuelle Commune fusionnée et variante toponymique Hameau dépendant Observation changement de nom Ablancourt Amblancourt Saint-Martin-d'Ablois Ablois Saint-Martin-d'Amblois, Ablois-Saint-Martin Par décret du 13/10/1952, Ablois devient Saint-Martin d'Ablois Aigny Allemanche-Launay-et-Soyer Allemanche-Launay Allemanche et Launay Par décret du 26 septembre 1846, Allemanche-Launay absorbe Soyer et prend le nom d'Allemanche-Launay-et- Soyer Allemanche-Launay-et-Soyer Soyer Par décret du 26 septembre 1846, Allemanche-Launay absorbe Soyer et prend le nom d'Allemanche-Launay-et- Soyer Allemant Alliancelles Ambonnay Par arrêté du 12/12/2005 Ambonnay dépend de l'arrondissement d'Epernay Ambrières Ambrières et Hautefontaine Par arrêté du 17/12/1965, modification des limites territoriales et échange de parcelles entre la commune d'Ambrières et celle de Laneuville-au-Pont (Haute-Marne) Anglure Angluzelles-et-Courcelles Angluzelle, Courcelles et Angluselle Anthenay Aougny Ogny Arcis-le-Ponsart Argers Arrigny Par décrets des 11/05/1883 et 03/11/1883 Arrigny annexe des portions de territoire de la commune de Larzicourt Arzillières-Neuville Arzillières Par arrêté préfectoral du 05/06/1973, Arzillières annexe Neuville-sous-Arzillières sous le nom de Arzillières-Neuville Arzillières-Neuville Neuville-sous-Arzillières Par arrêté préfectoral du 05/06/1973, Arzillières annexe Neuville-sous-Arzillières sous le nom de Arzillières-Neuville Athis Aubérive Aubilly Aulnay-l'Aître Aulnay-sur-Marne Auménancourt Auménancourt-le-Grand Par arrêté du 22/11/1966, Auménancourt-le-Grand absorbe Auménancourt-le-Petit et prend le nom d'Auménancourt Auménancourt Auménancourt-le-Petit Par arrêté du 22/11/1966, Auménancourt-le-Grand absorbe Auménancourt-le-Petit et prend le nom d'Auménancourt Auve Avenay-Val-d'Or Avenay Par décret du 28/05/1951, Avenay prend le nom d'Avenay- Val-d'Or. -

Picasso, L'éternel Féminin

Exposition temporaire Dossier pour les enseignants Service éducatif Musée des beaux-arts de Quimper Picasso, l’éternel féminin Sommaire Introduction p.3 1/ Ecce homo - Picasso, quelques repères chronologiques p.5 - Picasso, quelques repères formels p.9 2/ L’exposition - Picasso et le portrait p.11 - Les thèmes de l’exposition p.15 - Des femmes longuement portraiturées p.21 3/ La gravure - Picasso et la gravure p.27 - La production (schéma de synthèse) p.31 - Coups de projecteur La Suite Vollard - Les 357 - Les 156 p.33 - Glossaire de la gravure selon Picasso p.41 4/ Bibliographie p.47 5/ Propositions pédagogiques p.49 6/ Informations pratiques p.55 2 Picasso, l’éternel féminin Introduction Bâtie à partir des riches collections graphiques de la Fondation Picasso (Museo Casa Natal), Ville de Malaga, l’exposition présentée à Quimper puis à Pau décline l’importance du modèle féminin dans l’œuvre de Pablo Picasso. Au travers d’une sélection de près de 70 estampes, réalisées entre les années 1930 et 1970, et de plusieurs œuvres prêtées par des musées français, le public est invité à découvrir les multiples variations que l’artiste a créées autour de la femme. L’ensemble des gravures exposées, une première en France, permet de voir combien les femmes de la vie de Picasso mais aussi les femmes imaginées, rêvées et fantasmées, ont compté dans sa production artistique. Fernande, Marie-Thérèse, Dora, Françoise et Jacqueline ont marqué son œuvre qui brouille les frontières entre l’art et la vie. La gravure occupe une place privilégiée dans la pensée picturale de Picasso. -

Région Territoire De Vie-Santé Commune Code Département Code

Code Code Région Territoire de vie-santé Commune département commune Grand-Est Rethel Acy-Romance 08 08001 Grand-Est Nouzonville Aiglemont 08 08003 Grand-Est Rethel Aire 08 08004 Grand-Est Rethel Alincourt 08 08005 Grand-Est Rethel Alland'Huy-et-Sausseuil 08 08006 Grand-Est Vouziers Les Alleux 08 08007 Grand-Est Rethel Amagne 08 08008 Grand-Est Carignan Amblimont 08 08009 Grand-Est Rethel Ambly-Fleury 08 08010 Grand-Est Revin Anchamps 08 08011 Grand-Est Sedan Angecourt 08 08013 Grand-Est Rethel Annelles 08 08014 Grand-Est Hirson Antheny 08 08015 Grand-Est Hirson Aouste 08 08016 Grand-Est Sainte-Menehould Apremont 08 08017 Grand-Est Vouziers Ardeuil-et-Montfauxelles 08 08018 Grand-Est Vouziers Les Grandes-Armoises 08 08019 Grand-Est Vouziers Les Petites-Armoises 08 08020 Grand-Est Rethel Arnicourt 08 08021 Grand-Est Charleville-Mézières Arreux 08 08022 Grand-Est Sedan Artaise-le-Vivier 08 08023 Grand-Est Rethel Asfeld 08 08024 Grand-Est Vouziers Attigny 08 08025 Grand-Est Charleville-Mézières Aubigny-les-Pothées 08 08026 Grand-Est Rethel Auboncourt-Vauzelles 08 08027 Grand-Est Givet Aubrives 08 08028 Grand-Est Carignan Auflance 08 08029 Grand-Est Hirson Auge 08 08030 Grand-Est Vouziers Aure 08 08031 Grand-Est Reims Aussonce 08 08032 Grand-Est Vouziers Authe 08 08033 Grand-Est Sedan Autrecourt-et-Pourron 08 08034 Grand-Est Vouziers Autruche 08 08035 Grand-Est Vouziers Autry 08 08036 Grand-Est Hirson Auvillers-les-Forges 08 08037 Grand-Est Rethel Avançon 08 08038 Grand-Est Rethel Avaux 08 08039 Grand-Est Charleville-Mézières Les Ayvelles -

The Innovators Issue Table of Contents

In partnership with 51 Trailblazers, Dreamers, and Pioneers Transforming the Art Industry The Swift, Cruel, Incredible Rise of Amoako Boafo How COVID-19 Forced Auction Houses to Reinvent Themselves The Innovators Issue Table of Contents 4 57 81 Marketplace What Does a Post- Data Dive COVID Auction by Julia Halperin • What sold at the height of the House Look Like? COVID-19 shutdown? by Eileen Kinsella • Which country’s art • 3 top collectors on what they market was hardest hit? buy (and why) The global shutdown threw • What price points proved the live auction business into • The top 10 lots of 2020 (so far) most resilient? disarray, depleting traditional in every major category houses of expected revenue. • Who are today’s most Here’s how they’re evolving to bankable artists? 25 survive. The Innovators List 65 91 At a time of unprecedented How Amoako Art Is an Asset. change, we scoured the globe Boafo Became the Here’s How to to bring you 51 people who are Breakout Star of Make Sure It changing the way the art market Works for You functions—and will play a big a Pandemic Year role in shaping its future. In partnership with the by Nate Freeman ART Resources Team at Morgan Stanley The Ghanaian painter has become the art industry’s • A guide to how the art market newest obsession. Now, he’s relates to financial markets committed to seizing control of his own market. • Morgan Stanley’s ART Resources Team on how to integrate art into your portfolio 2 Editors’ Letter The COVID-19 pandemic has forced the art world to reckon with quite a few -

Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris

MEDIA RELEASE ‘If the progress of 20th-century art was to be defined by the achievements of a single individual, that individual would indisputably be Picasso.’ Edmund Capon PICASSO Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris SYDNEY ONLY 12 November 2011 – 25 March 2012 ART GALLERY NSW ART GALLERY NSW 1922 1904 ‘I paint the way some people write their autobiography. The paintings, finished or not, are the pages from my diary…’ Pablo Picasso 1932 clockwise from top left: La Célestine (La Femme à la taie) (La Celestina (The woman with a cataract) 1904 Deux femmes courant sur la plage (La course) (Two women running on the beach (The race) 1922 Femmes à la toilette (Women at their toilette) 1956 La lecture (The reader) 1932 1956 ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES / 5 ART GALLERY NSW 1906 1937 1950 clockwise from top left: Portrait de Dora Maar (Portrait of Dora Maar) 1937 Autoportrait (Self-portrait) 1906 La chèvre (The goat) 1950 Le baiser (The kiss) 1969 1969 ART GALLERY OF NEW SOUTH WALES / 2 PICASSO Masterpieces from the Musée National Picasso, Paris Picasso in front of Portrait de femme by Henri Rousseau 1932, photo by Brassaï ‘This is the great Picasso show to which ‘This exceptional exhibition covering we have often aspired but not yet achieved every aspect of Picasso’s multifaceted in Australia. Make the most of it because output and all the artistic media in which we will never have such a show again. he exercised his extraordinary creativity, Seven decades of Picasso’s relentless work, constitutes the foundation stone for a capturing every phase of his extraordinary groundbreaking partnership between the career, including masterpieces from his Blue, Musée National Picasso and the Art Gallery Rose, Expressionist, Cubist, Neoclassical and of New South Wales.’ Surrealist periods. -

95 Communes Rassemblant Au Total 35 587 Habitants (Selon Données INSEE 2012)

Liste des communes constitutives du GAL Brie et Champagne Le GAL du Pays de Brie et Champagne est constitué de 95 communes rassemblant au total 35 587 habitants (selon données INSEE 2012). Voici la liste des communes qui constituent son périmètre : Nombre N° Nom de la commune d'habitants EPCI INSEE (INSEE 2012) 1 Allemanche-Launay-et-Soyer 51004 106 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 2 Allemant 51005 168 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 3 Anglure 51009 826 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 4 Angluzelles-et-Courcelles 51010 144 CC du Sud Marnais 5 Bagneux 51032 496 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 6 Bannes 51035 282 CC du Sud Marnais 7 Barbonne-Fayel 51036 494 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 8 Baudement 51041 121 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 9 Bergères-sous-Montmirail 51050 131 CC de la Brie Champenoise 10 Bethon 51056 287 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 11 Boissy-le-Repos 51070 201 CC de la Brie Champenoise 12 Bouchy-Saint-Genest 51071 186 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 13 Broussy-le-Grand 51090 312 CC du Sud Marnais 14 Broussy-le-Petit 51091 128 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 15 Broyes 51092 366 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 16 Champguyon 51116 269 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 17 Chantemerle 51124 52 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 18 Charleville 51129 280 CC de la Brie Champenoise 19 Chichey 51151 167 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 20 Châtillon-sur-Morin 51137 187 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 21 Clesles 51155 602 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 22 Conflans-sur-Seine 51162 674 CC Sézanne Sud-Ouest marnais 23 Connantray-Vaurefroy 51164 180 CC du Sud Marnais 24 Connantre 51165 -

Pacte Territorial Et Plan Départemental D'insertion De La Marne

2019-2021 Pacte Territorial et Plan Départemental d’Insertion de la Marne Pacte Territorial et Plan Départemental d’Insertion de la Marne • Éditorial ÉDITORIAL La loi n°2008-1249 du 1er décembre 2008 géné- de gouvernance qui a pour objet de coordonner ralisant le Revenu de Solidarité Active (RSA) et les actions d’insertion dans le respect des préroga- réformant les politiques d’insertion a confié au tives de chaque partenaire. Département la compétence et la responsabilité Il s’appuie à cet effet sur unProgramme Dépar- de la mise en œuvre du RSA et l’a ainsi conforté temental d’Insertion (PDI) dont l’objet est de dans son rôle de chef de file des politiques d’in- définir sa politique d’accompagnement social et sertion. professionnel, de recenser les besoins et offres Cette responsabilité implique une vigilance toute d’insertion locaux et de planifier les actions d’in- particulière en termes de coordination des actions sertion correspondantes (article L.263-1 du CASF). menées au profit de l’insertion sociale et profes- Au-delà de l’accompagnement effectif assuré par sionnelle des publics par l’ensemble de ses parte- le Département et ses principaux partenaires, les naires. enjeux que constituent l’accès aux droits et la Le dispositif RSA et la création de la prime d’acti- pertinence de l’orientation impliquent l’élabora- vité à la suite de la réforme de 2016 ont élargi le tion d’une convention d’orientation prévue aux champ des publics concernés initialement par le articles L262-27 à L262-29 du CASF. -

LA CCSSOM › Le Mag LE MAGAZINE D’INFORMATION DE LA COMMUNAUTÉ DE COMMUNES DE SÉZANNE SUD-OUEST MARNAIS

DÉCEMBRE 2018 / N° 01 / www.ccssom.fr / Retrouvez-nous sur les réseaux sociaux LA CCSSOM › le mag LE MAGAZINE D’INFORMATION DE LA COMMUNAUTÉ DE COMMUNES DE SÉZANNE SUD-OUEST MARNAIS DOSSIER L’analyse des besoins sociaux Allemanche-Launay-et-Soyer | Allemant | Anglure | Bagneux | Barbonne-Fayel | Baudement | Bethon | Bouchy- Saint-Genest | Broussy-le-Petit | Broyes | Champguyon | Chantemerle | Châtillon-sur-Morin | Chichey | Clesles Conflans-sur-Seine | Courcemain | Courgivaux | Escardes | Esclavolles-Lurey | Esternay | Fontaine-Denis- Nuisy | Gaye | Granges-sur-Aube | Joiselle | La Celle-sous-Chantemerle | La Chapelle-Lasson | La Forestière La Noue | Lachy | Le Meix-Saint-Époing | Les Essarts-le-Vicomte | Les Essarts-lès-Sézanne | Linthelles Linthes | Marcilly-sur-Seine | Marsangis | Mœurs-Verdey | Mondement-Montgivroux | Montgenost | Nesle- la-Reposte | Neuvy | Oyes | Péas | Potangis | Queudes | Reuves | Réveillon | Saint-Bon | Saint-Just-Sauvage Saint-Loup Saint-Quentin-le-Verger | Saint-Remy-sous-Broyes | Saint-Saturnin | Saron-sur-Aube | Saudoy Sézanne Villeneuve-la-Lionne | Villeneuve-Saint-Vistre-et-Villevotte | Villiers-aux-Corneilles | Vindey | Vouarces DÉCEMBRE 2018 / N°1 / LA CCSSOM › LE MAG 1 › Sommaire 03 / RETOUR EN IMAGES Retrouvez les principaux travaux d’aménagement des mois écoulés Gérard AMON Président de la Communauté 05 / ACTUS de Communes de Sézanne 05 Tourisme / Budget / Urbanisme Sud-Ouest Marnais 06 Environnement Maire de Joiselle 07 Aménagement du territoire 2 questions à… › Que pensez-vous de l’évolution de la fiscalité sur notre territoire et plus largement à l’échelle nationale ? 08 / DOSSIER L’harmonisation des taux dès 2017 sur les trois ex-communautés de L’analyse des besoins sociaux communes : Portes de Champagne (CCPC), Pays d’Anglure (CPPA) et Coteaux Sézannais (CCCS), n’a pas entraîné de hausse significative de 10 / ZOOM SUR..