An Apartment in Paris - Travel Stories

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY of P. A. RENOIRS' PAINTINGS Iwasttr of Fint Girt

AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF P. A. RENOIRS' PAINTINGS DISSERTATION SU8(N4ITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIfJIMENTS FOR THE AWARD OF THE DEGREE OF iWasttr of fint girt (M. F. A.) SABIRA SULTANA '^tj^^^ Under the supervision of 0\AeM'TCVXIIK. Prof. ASifl^ M. RIZVI Dr. (Mrs) SIRTAJ RlZVl S'foervisor Co-Supei visor DEPARTMENT OF FINE ART ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY ALIGARH (INDIA) 1997 Z>J 'Z^ i^^ DS28S5 dedicated to- (H^ 'Parnate ALIGARH MUSLIM UNIVERSITY CHAIRMAN DEPARTMENT OF FINE ARTS ALIGARH—202 002 (U.P.), INDIA Dated TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN This is to certify that Sabera Sultana of Master of Fine Art (M.F.A.) has completed her dissertation entitled "AN ANALYTICAL STUDY OF P.A. RENOIR'S PAINTINGS" under the supervision of Prof. Ashfaq M. Rizvi and co-supervision of Dr. (Mrs.) Sirtaj Rizvi. To the best of my knowledge and belief the work is based on the investigations made, data collected and analysed by her and it has- not been submitted in any other university or Institution for any degree. Mrs. SEEMA JAVED Chairperson m4^ &(Mi/H>e& of Ins^tifHUion/, ^^ui'lc/aace' cm^ eri<>ouruae/riefity: A^ teacAer^ and Me^^ertHs^^r^ o^tAcsy (/Mser{xUlafi/ ^rof. £^fH]^ariimyrio/ar^ tAo las/y UCM^ accuiemto &e^£lan&. ^Co Aasy a€€n/ kuid e/KHc^ tO' ^^M^^ me/ c/arin^ tA& ^r€^b<ir<itlan/ of tAosy c/c&&erla6iafi/ and Aasy cAecAe<l (Ao contents' aMd^yormM/atlan&^ arf^U/ed at in/ t/ie/surn^. 0A. Sirta^ ^tlzai/ ^o-Su^benn&o^ of tAcs/ dissertation/ Au&^^UM</e^m^o If^fi^^ oft/us dissertation/, ^anv l>eAo/den/ to tAem/ IhotA^Jrom tAe/ dee^ o^nu^ l^eut^. -

Impressionist Adventures

impressionist adventures THE NORMANDY & PARIS REGION GUIDE 2020 IMPRESSIONIST ADVENTURES, INSPIRING MOMENTS! elcome to Normandy and Paris Region! It is in these regions and nowhere else that you can admire marvellous Impressionist paintings W while also enjoying the instantaneous emotions that inspired their artists. It was here that the art movement that revolutionised the history of art came into being and blossomed. Enamoured of nature and the advances in modern life, the Impressionists set up their easels in forests and gardens along the rivers Seine and Oise, on the Norman coasts, and in the heart of Paris’s districts where modernity was at its height. These settings and landscapes, which for the most part remain unspoilt, still bear the stamp of the greatest Impressionist artists, their precursors and their heirs: Daubigny, Boudin, Monet, Renoir, Degas, Morisot, Pissarro, Caillebotte, Sisley, Van Gogh, Luce and many others. Today these regions invite you on a series of Impressionist journeys on which to experience many joyous moments. Admire the changing sky and light as you gaze out to sea and recharge your batteries in the cool of a garden. Relive the artistic excitement of Paris and Montmartre and the authenticity of the period’s bohemian culture. Enjoy a certain Impressionist joie de vivre in company: a “déjeuner sur l’herbe” with family, or a glass of wine with friends on the banks of the Oise or at an open-air café on the Seine. Be moved by the beauty of the paintings that fill the museums and enter the private lives of the artists, exploring their gardens and homes-cum-studios. -

Myths, Legends, Fairy Tales and Folk Tales in Music ______

______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Sounds of Enchantment: Myths, Legends, Fairy Tales and Folk Tales in Music ______________________________________________________________________________________________________ Gioacchino ROSSINI Overture from William Tell Felix MENDELSSOHN Scherzo from A Midsummer Night’s Dream Sergei PROKOFIEV Waltz Coda and Midnight from Cinderella, Op. 87 David CROWE How Birds Came Into the World John WILLIAMS Raiders March from Raiders of the Lost Ark Piotr Ilyich TCHAIKOVSKY Scene from Swan Lake Modest MUSSORGSKY / arr. Ravel Baba Yaga and The Great Gate of Kiev from Pictures at an Exhibition HOW TO USE THIS STUDY GUIDE This guide is designed as a curriculum enhancement resource primarily for music teachers, but is also available for use by classroom teachers, parents, and students. The main intent is to aid instructors in their own lesson preparation, so most of the language and information is geared towards the adult, and not the student. It is not expected that all the information given will be used or that all activities are applicable to all settings. Teachers and/or parents can choose the elements that best meet the specific needs of their individual situations. Our hope is that the information will be useful, spark ideas, and make connections. TABLE OF CONTENTS Sounds of Enchantment Overview – Page 4 Program Notes – Page 7 ROSSINI | Overture from William Tell Page 8 MENDELSSOHN | Scherzo from A Midsummer Night’s Dream Page 10 PROKOFIEV | Waltz Coda and Midnight from Cinderella, Op. 87 Page 13 CROWE | How Birds Came Into the World Page 17 WILLIAMS | Raiders March from Raiders of the Lost Ark Page 20 TCHAIKOVSKY | Scene from Swan Lake Page 22 MUSSORGSKY | Baba Yaga and The Great Gate of Kiev from Pictures at an Exhibition Page 24 Activities — Page 27 Student Section— Page 39 CREDITS This guide was originally created for the 2008-2009 Charlotte Symphony Education Concerts by Susan Miville, Chris Stonnell, Anne Stewart, and Jane Orrell. -

Mise En Page 1

900x210 24/02/12 18:20 Page 1 H LA MAISON FOURNAISE LE RENDEZ-VOUS DES IMPRESSIONNISTES LES DEUX FAUVES DE CHATOU UN DÉJEUNER À WASHINGTON LES COLLECTIONS DU MUSÉE LES ANIMATIONS DU MUSÉE FOURNAISE ADÉCOUVRIR SUR L’ILE DES IMPRESSIONNISTES COMMENT YACCÉDER : ANDRÉ DERAIN ET MAURICE DE VLAMINCK Le musée Fournaise conserve Individuel mo mo OURNAISE O F U Célèbre guinguette des bords de Seine, le charme du lieu attire ET DES ÉCRIVAINS André Derain (né à Chatou) et Maurice de Vlaminck installent leur Ce tableau, Le Déjeuner des Canotiers, est mondialement reconnu des collections picturales et • Visite audio-guide français, anglais, allemand 6e Renoir. Sur le balcon de la maison, il peint son célèbre Déjeuner Claude Monet, Alfred Sisley, Berthe atelier en 1900 dans une maison comme étant un chef-d’œuvre de l’impressionnisme. graphiques sur l’histoire de la • Visite sans audio-guide S museum and E des Canotiers à la fin de l’été en 1880. Morisot, Edouard Manet, Camille voisine du restaurant Fournaise, En 1924, Duncan Phillips et son épouse Isadora l’acquièrent pour le Maison Fournaise et du cano- Plein tarif 5e PAR LA ROUTE : A Pissarro, Pierre Prins, arpentent l’île la Maison Levanneur. Guillaume premier musée privé américain d’art moderne et considèrent alors tage. Elle comprend notamment Tarif réduit (sur justificatif) 3e Croisière à bord du Dénicheur, Adresse GPS : restaurant 3 rue du Bac - 78400 Chatou 10 km de que le monde entier se déplacera jusqu’à Washington pour une remarquable collection de • Visite guidée tous les dimanches à 15h 6e bateau électrique en quête de cette lumière mobile sur Apollinaire et Henri Matisse leur Depuis Paris, prendre les autoroutes PARIS l’admirer. -

CIVIL AIR PATROL September-October 2006

cap volunteer Sept-Oct 06 11/2/06 7:35 AM Page a CIVIL AIR PATROL September-October 2006 Everyday Heroes of the U.S. Air Force Auxiliary SUPER SUMMER Cadets Excel at NCC, Other Activities 9/11 CALLS MEMBERS Patriotism Leads Volunteers Into CAP ACADEMY BOUND CAP Postures Cadets For Next Level cap volunteer Sept-Oct 06 11/2/06 7:35 AM Page b cap volunteer Sept-Oct 06 11/2/06 7:35 AM Page 1 CIVIL AIR PATROL September-October 2006 FEATURES 2 9/11 Impacts Membership Five years later, members share inspiration for joining. 6 Border Sorties National commander testifies before House committee. 9 Sea of Red CAP members take part in Red Ribbon Week. 2 The tragic events of Sept. 11, 2001, had 11 Georgia Wing on Their Minds a profound effect on CAP membership. Unit’s missions gain praise from State House. 12 Animal Instinct 40 Wings of Freedom Feline friends help CAP hone search skills. Pilot of historic bombers says CAP gave him aviation bug. 16 Aerospace and Beyond CAP member spreads AE message across nation. 42 On the Marking Cadet embodies, shares spirit of CAP. 18 Blind? No Problem! Cadet shares his CAP experience. 46 Springboard to Success Cadets sail from CAP to military academies. 20 Ham and CAP Go Great Together Members promote CAP at Hamvention. 21 Seasonal Sensations DEPARTMENTS Centerfold pullout features cadet summer programs. 5 From Your National Commander 22 Lead to Succeed 51 Achievements Cadet Officer School readies youth for careers, life. Officers, Cadets Honored 24 Egg-citing School National Staff College prepares members to lead. -

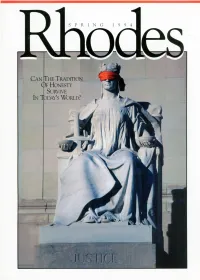

Fifi'; 11( from the Editor

S P R I N G 1 9 9 4 ammo CAN HE TRADITI OF HONESTY * SURVIVE DAY'S WORLD? fifi'; 11( From The Editor Rhode S (ISSN 40891-6446) is (From left) published tour times a year in spring, summer, Executive fall and winter by Rhodes College, 2000 N. Editor Helen Norman, Parkway, Memphis, TN 38112-1690. It is pub- Contributing lished as a service to all alumni, students, par- Editor Susan ents, faculty, staff and friends of the college. McLain Sullivan, Art Spring 1994 —Volume 1, Number I. Second Director Trey class postage paid at Memphis, Tennessee and Clark '89, additional mailing offices. and Editor Martha Hunter EXECUTIVE EDITOR: Helen Watkins Norman Shepard '66. EDITOR: Martha Hunter Shepard '66 Welcome to Rhodes, the magazine created especially for and about Rhodes Art Director: Trey Clark '89 alumni, parents, friends, faculty, staff and students. CONTRIBUTING EDITOR: Susan McLain Like the Rhodes Today, which it replaces, the magazine will continue to keep Sullivan you informed about what's happening day to day on campus and in the lives of POSTMASTER: Send address changes to: our alumni. But it will also offer you the chance to sample a broader mix of Rhodes, 2000 North Parkway, Memphis, TN 38112-1690. Rhodes-related articles and in greater depth than possible in the former publica- tion. The aim is for Rhodes to be more visually appealing as well, with an up-to- CHANGE OF ADDRESS: Please mail the complet- ed form below and label from this issue of Rhodes date design (for which we thank Memphis designer Eddie Tucker) and an ample to: Alumni Office, Rhodes College, 2000 North serving of color photography. -

Site/Non-Site Explores the Relationship Between the Two Genres Which the Master of Aix-En- Provence Cultivated with the Same Passion: Landscapes and Still Lifes

site / non-site CÉZANNE site / non-site Guillermo Solana Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza, Madrid February 4 – May 18, 2014 Fundación Colección Acknowledgements Thyssen-Bornemisza Board of Trustees President The Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza Hervé Irien José Ignacio Wert Ortega wishes to thank the following people Philipp Kaiser who have contributed decisively with Samuel Keller Vice-President their collaboration to making this Brian Kennedy Baroness Carmen Thyssen-Bornemisza exhibition a reality: Udo Kittelmann Board Members María Alonso Perrine Le Blan HRH the Infanta Doña Pilar de Irina Antonova Ellen Lee Borbón Richard Armstrong Arnold L. Lehman José María Lassalle Ruiz László Baán Christophe Leribault Fernando Benzo Sáinz Mr. and Mrs. Barron U. Kidd Marina Loshak Marta Fernández Currás Graham W. J. Beal Glenn D. Lowry HIRH Archduchess Francesca von Christoph Becker Akiko Mabuchi Habsburg-Lothringen Jean-Yves Marin Miguel Klingenberg Richard Benefield Fred Bidwell Marc Mayer Miguel Satrústegui Gil-Delgado Mary G. Morton Isidre Fainé Casas Daniel Birnbaum Nathalie Bondil Pia Müller-Tamm Rodrigo de Rato y Figaredo Isabella Nilsson María de Corral López-Dóriga Michael Brand Thomas P. Campbell Nils Ohlsen Artistic Director Michael Clarke Eriko Osaka Guillermo Solana Caroline Collier Nicholas Penny Marcus Dekiert Ann Philbin Managing Director Lionel Pissarro Evelio Acevedo Philipp Demandt Jean Edmonson Christine Poullain Secretary Bernard Fibicher Earl A. Powell III Carmen Castañón Jiménez Gerhard Finckh HSH Prince Albert II of Monaco Giancarlo Forestieri William Robinson Honorary Director Marsha Rojas Tomàs Llorens David Franklin Matthias Frehner Alejandra Rossetti Peter Frei Katy Rothkopf Isabel García-Comas Klaus Albrecht Schröder María García Yelo Dieter Schwarz Léonard Gianadda Sir Nicholas Serota Karin van Gilst Esperanza Sobrino Belén Giráldez Nancy Spector Claudine Godts Maija Tanninen-Mattila Ann Goldstein Baroness Thyssen-Bornemisza Michael Govan Charles L. -

Dossier De Presse

DOSSIER DE PRESSE LA FAMILLE RENOIR A ESSOYES L’attachement de Renoir à ce petit village de Champagne est bien réel, mais trop peu connu du grand public. Grâce à Aline Charigot, originaire de notre commune, c’est la Champagne tout entière que le peintre Auguste Renoir épouse. Il est rapidement conquis par Essoyes, c’est là qu’il rencontre Gabrielle qui deviendra son célèbre modèle et la nourrice de son fils Jean. C’est pendant plus de 30 années, que Renoir passera les étés à Essoyes. Nombreux sont les amis célèbres à le rejoindre pour un moment de détente et de bonne humeur. Son dernier fils Claude dit « Coco » y verra le jour le 4 Août 1901 et Jean suivra les cours de l’école communale. Jusqu’en 2011, l’Association Renoir a fait revivre l’atelier du peintre et c’est à cette date que la Commune a inauguré le « site culturel et touristique » qui a accueilli 21000 visiteurs en 2017 avec l’ouverture au public de la maison familiale des Renoir. Ce site est labellisé « Vignobles et Découverte » et « Maison des Illustres » en 2011 pour l’atelier du peintre. Aline meurt en 1915. Renoir continue, malgré ses mains déformées et la souffrance, de peindre jusqu'à sa mort le 3 Décembre 1919 au Domaine des Collettes à Cagnes-sur-Mer. Initialement enterré avec son épouse dans le vieux cimetière du château de Nice, les dépouilles du couple Renoir sont transférées le 7 juin 1922 dans le département de l'Aube où elles reposent désormais dans le cimetière d’Essoyes en Champagne comme l'avaient décidé « le Peintre du Bonheur » et son épouse Aline originaire du village. -

LH Women of Military Service, We Salute You... Page 17

March 2014 The Official Magazine of Sun CompassCity Lincoln Hills 2014 Board of Directors... page 2 Remembering Rosie... page 7 What's New at Kilaga LH Women of Military Springs Café... page 10 Service, We Salute You... page 17 Association News Board of Directors Report ActivitiesIn News & HappeningsThis ................................. Issue 5, 44 Marcia VanWagner, Director, SCLH Board of Directors Ad Directory / Compass Advertisers .......................... 103 n February 20, about 20 residents wants this to be the best Aging Well: Do You Sleep Beautifully? ......................... 9 attended the Annual Meeting of community we can have and An Opportunity to Enrich Your Life: Lincoln Wine Fest .... 19 OMembers of the Lincoln Hills Com- that we all work very hard to ARC/Architectural Review Committee ...................... 10 munity Association. And we even had free achieve that goal. Association Contacts & Hours Directory ...................... 102 coffee! Because there was no quorum, the Part of our work is serving as liaisons Board of Directors Report........................................... 2 meeting was adjourned as no business to the Association committees. Jim Le- Bulletin Board ..................................................... 39 could take place without a quorum. The onhard, as Treasurer, will represent the • You Are Invited ............................................... 39 Special Board Meeting was convened and Board on the Finance Committee, Marcia • Community Perks ................................................... -

Dark Matter #4

Cover Page DarkIssue Four Matter July 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Issue Four July 2011 SF, Fantasy & Art [email protected] Dark Matter Contents: Issue 4 Dark Matter Stuff 1 News & Articles 7 Gun Laws & Cosplay 7 Troopertrek 2011 8 Hugo Award Nominees 10 2010 Aurealis Awards 14 2011 Aurealis Awards to be held in Sydney again 15 2011 Ditmar Awards 16 2011 Chronos Awards 20 Renovation WorldCon 22 Iron Sky update 28 Art by Ben Grimshaw 30 Ebony Rattle as Electra, Art by Ben Grimshaw 31 The Girl in the Red Hood is Back … But She’s a Little Different 32 Launching & Gaining Velocity 34 Geek and Nerd 35 Peacemaker - A Comic Book 36 Continuum 7 Report 38 Starcraft 2 - Prae.ThorZain 46 Good Friday Appeal 50 FAQ about the writing of Machine Man, by Max Barry 65 J. Michael Straczynski says... 67 Interviews 69 Kevin J. Anderson talks to Dark Matter 69 Tom Taylor and Colin Wilson talk to Dark Matter 78 Simon Morden talks to Dark Matter 106 Paul Bedford talks to Dark Matter 115 Cathy Larsen talks to Dark Matter 131 Madeleine Roux talks to Daniel Haynes 142 Chewbacca is Coming 146 Greg Gates talks to Dark Matter 153 Richard Harland talks to Dark Matter 165 Letters 173 Anime/Animation 176 The Sacred Blacksmith Collection 176 Summer Wars 177 Evangelion 1.11 You are [not] alone 178 Evangelion 2.22 You can [not] advance 179 Book Reviews 180 The Razor Gate 180 Angelica 181 2 issue four The Map of Time 182 Die for Me 183 The Gathering 184 The Undivided 186 the twilight saga: the official illustrated guide 188 Rivers -

ONAPI Firma Convenio Con La UASD Y Capacita a Funcionarios Para La Entrada En Vigencia Del PCT

Año 7 • Volumen 151, Mayo, 2007 JUEVES 31 DE MAYO DE 2007 ONAPI firma convenio con la UASD y capacita a funcionarios para la entrada en vigencia del PCT La Oficina Nacional de Propiedad Industrial materia de Patentes (PCT), ONAPI ofreció (ONAPI) firmó un acuerdo de cooperación un seminario con el interés de capacitar a interinstitucional con la Universidad sus funcionarios con la participación de Autónoma de Santo Domingo (UASD), con expertos internacionales de la OMPI. el objetivo de establecer una colaboración en el campo de la docencia, investigación, A partir del 28 de mayo del presente año, capacitación y el intercambio de tecnología República Dominicana tiene la asignación durante un acto celebrado en el Salón de automática en toda solicitud internacional de Consejo de la rectoría de la alta casa de patente, y que todos los nacionales y estudios. residentes en el país tienen derecho a presentar solicitudes en virtud de este La firma estuvo encabezada por el Lic. tratado al entrar en vigencia el Tratado de Enrique Ramírez, director general de Libre Comercio con Estados Unidos y ONAPI y el doctor Roberto Reyna, rector de Centroamérica. la UASD, quienes se comprometieron además instalar dentro del recinto de la El director general, Enrique Ramírez dio la universidad una oficina de patentes, la cual bienvenida a Rolando Hernández Vigaud y funcionará como receptora de solicitudes, Carlos Roy, representantes de la OMPI, siendo ONAPI responsable de administrar el quienes durante toda una semana régimen de los derechos de la Propiedad ofrecieron un entrenamiento al personal de Industrial en la República Dominicana. -

Renoir, Impressionism, and Full-Length Painting

FIRST COMPREHENSIVE STUDY OF RENOIR’S FULL-LENGTH CANVASES BRINGS TOGETHER ICONIC WORKS FROM EUROPE AND THE U.S. FOR AN EXCLUSIVE NEW YORK CITY EXHIBITION RENOIR, IMPRESSIONISM, AND FULL-LENGTH PAINTING February 7 through May 13, 2012 This winter and spring The Frick Collection presents an exhibition of nine iconic Impressionist paintings by Pierre-Auguste Renoir, offering the first comprehensive study of the artist’s engagement with the full-length format. Its use was associated with the official Paris Salon from the mid-1870s to mid- 1880s, the decade that saw the emergence of a fully fledged Impressionist aesthetic. The project was inspired by Renoir’s La Promenade of 1875–76, the most significant Impressionist work in the Frick’s permanent collection. Intended for public display, the vertical grand-scale canvases in the exhibition are among the artist’s most daring and ambitious presentations of contemporary subjects and are today considered masterpieces of Impressionism. The show and accompanying catalogue draw on contemporary criticism, literature, and archival documents to explore the motivation behind Renoir’s full-length figure paintings as well as their reception by critics, peers, and the public. Recently-undertaken technical studies of the canvases will also shed new light on the artist’s working methods. Works on loan from international institutions are La Parisienne from Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), Dance at Bougival, 1883, oil on canvas, 71 5/8 x 38 5/8 inches, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Picture Fund; photo: © 2012 Museum the National Museum Wales, Cardiff; The Umbrellas (Les Parapluies) from The of Fine Arts, Boston National Gallery, London (first time since 1886 on view in the United States); and Dance in the City and Dance in the Country from the Musée d’Orsay, Paris.